York, Newcastle and Berwick Railway

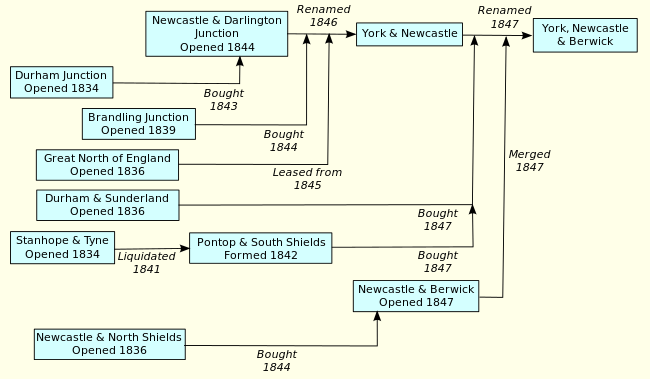

The York, Newcastle and Berwick Railway (YN&BR) was an English railway company formed in 1847 by the amalgamation of the York and Newcastle Railway and the Newcastle and Berwick Railway. Both companies were part of the group of business interests controlled by George Hudson, the so-called Railway King. In collaboration with the York and North Midland Railway and other lines he controlled, he planned that the YN&BR would form the major part of a continuous railway between London and Edinburgh. At this stage the London terminal was Euston Square (nowadays called Euston) and the route was through Normanton. This was the genesis of the East Coast Main Line, but much remained to be done before the present-day route was formed, and the London terminus was altered to King's Cross.

The YN&BR completed the plans of its predecessors, including building a central passenger station in Newcastle, the High Level Bridge across the River Tyne, and the viaduct across the River Tweed, that was later named the Royal Border Bridge. These were prodigious undertakings.

George Hudson's business methods had always been uncompromising, and eventually serious irregularities in his financial dealings were exposed, which led to his disgrace and resignation from the chairmanship of the YN&BR in 1849.

Co-operation with other railways in the YN&BR area led to a traffic sharing agreement, and then to amalgamation; on 31 July 1854 the North Eastern Railway was formed by the merger of the YN&BR with the Leeds Northern Railway and the York & North Midland Railway, as well as the Malton and Driffield Junction Railway three months later.

Early railways

The abundant mineral deposits in the area of County Durham and Northumberland led early on to the construction of waggonways to convey the heavy ores to watercourses for onward transit, or to other means of reaching a point of sale.

Tanfield Waggonway

Although there appear to have been earlier waggonways from the high ground around Tanfield, the most notable line was the Tanfield Waggonway of 1725, from Tanfield Moor to Dunston, on the Tyne. This line had several rope-worked inclines, with more moderate gradients operated by horse traction. The rails were timber. In commercial terms it was remarkably successful, although wayleave charges (imposed by landowners) were heavy.[1]

The Stanhope and Tyne Railway

The Stanhope and Tyne Railroad Company was formed in 1832 as a partnership to build a railway between limestone quarries near Stanhope and the coal mines near Medomsley, and to connect to quays at South Shields.[2][3]

The line was opened in 1834. There were several rope-worked inclines on the route.[4][5][6]

Traffic levels did not reach expectations, some collieries on the route declining to use the line, and the heavy operating costs of the inclined planes lead to poor profitability. When it was discovered that the directors had been overstating the profitability of the concern, a financial crisis was precipitated. In 1842 it became obvious that the Stanhope and Tyne company could not continue and a new company was formed to take on the debt and operate the railway.

Pontop and South Shields Railway

The new company was the Pontop and South Shields Railway of 1842. The south-western part of the line from Stanhope to Carrhouse was sold to the Derwent Iron Company, which operated at Consett. It formed an alliance with the Stockton and Darlington Railway and in time a railway connection through Bishop Auckland and that section became part of the Stockton and Darlington Railway system.

From 1840 passenger traffic increased when through trains from London to Gateshead ran over part of the P&SSR line, in association with the Newcastle and Darlington Junction Railway, the Durham Junction Railway, and the Brandling Junction Railway.[7]

The Newcastle and Darlington Junction Railway acquired the Pontop and South Shields Railway on 1 January 1847[8][9]

Brandling Junction Railway

John and Robert William Brandling had extensive mining interests in the area east of Gateshead and in the Tanfield area. They took steps to build a railway connecting their interests with quays at South Shields and Wearmouth, and in 1835 formed the Brandling Junction Railway.

It opened in 1839 from a Gateshead station at Oakwellgate, to South Shields and Wearmouth. The company also acquired the Tanfield Waggonway and modernised it. Its terminal on the Tyne at Dunston required the use of keels to convey the coal downstream to shipping berths, requiring transshipping, and the Brandling Junction Railway opened a connection from the Tanfield line to Oakwellgate too, to bring the Tanfield coal to deeper water. This required the use of a short section of the Newcastle and Carlisle Railway near Redheugh. [10][11]

From 1840 passenger trains from London to Gateshead used the Brandling Junction line from Brockley Whins to Gateshead.

The Brandling Junction Railway was taken over by the Newcastle and Darlington Junction Railway in 1844.

Hartlepool Dock & Railway

Hartlepool–Haswell–Sunderland Line and Hartlepool–Ferryhill Line | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Hartlepool Dock & Railway (HD&R) was built to take coal from central County Durham mines to the docks at Hartlepool. A private bill was presented to Parliament seeking permission to build the railway and Royal Assent was given on 1 June 1832. The line was 14 miles (23 km) long with 9 1⁄4 miles (14.9 km) of branch line, and 65 acres (26 ha) of land for docks; a later Act gave authority for a branch to the City of Durham and the use of stationary engines. The line was not built beyond Haswell after no assurances could be obtained from the owners of Moorsley and Littletown collieries that they would use the line to send coal to Hartlepool. Services ran between Thornley pit and Castle Eden after January 1835; on 23 November that year the first train ran the 12 1⁄4 miles (19.7 km) between Haswell and Hartlepool. By the end of that year there was 14 1⁄2 miles (23.3 km) of line operational.[12]

The Great North of England, Clarence & Hartlepool Junction Railway (GNEC&HJR) was a 8 1⁄2-mile (13.7 km) extension of the HD&R from Wingate to the Great North of England Railway at Ferryhill and the Clarence Railway at Byers Green. An Act was obtained on 3 July 1837[13] and the line opened to Kelloe Bank in 1839.[14] The GNEC&HJR had neglected to obtain powers to cross the Clarence Railway's Sherburn branch and returned to Parliament after failing to come to agreement with the Clarence. Royal Assent was given in 1843 for a bridge over the line, but the Clarence Railway still refused to cooperate building it, so it was 1846 before the railway was completed[15] The York & Newcastle Railway leased the HD&R and GNEC&HJR from 12 August 1846, and both were amalgamated with the York, Newcastle and Berwick Railway on 22 July 1848.[9]

Durham Junction Railway

On 16 June 1834 the Durham Junction Railway (DJR) received permission to build a railway to transport coal from Moorsley in the Houghton-le-Spring area and the Hartlepool Dock & Railway to the River Tyne at Gateshead.[16][17] Leaving the Stanhope and Tyne line at Washington, the River Wear was crossed by Victoria Viaduct, 811 feet (247 m) long and 135 feet (41 m) above high-water mark, which was designed by Harrison and built in two years. The bridge was officially opened and named in honour of Queen Victoria on her coronation on 28 June 1838, and the railway opened to mineral traffic on 24 August 1838. The 4-mile-70-chain (7.8 km) long line was only laid as far as Rainton Meadows, 2 miles (3.2 km) short of Moorsley, and the Houghton-le-Spring branch was not built.[16][18]

Passengers were carried over the railway for the first time in March 1840 as one of the series of connecting services between Newcastle and Darlington.[19] On 14 September 1843 the company was bought by N&DJR, as its planned route between Newcastle and Darlington involved running over the railway and the DJR was operating at a loss and unable to upgrade the track.[20][21]

Durham & Sunderland Railway

The Durham & Sunderland Railway (D&SR) received permission on 13 August 1834 for a 13 1⁄4-mile (21.3 km) line from the South Dock in Sunderland to Murton, with branches to Durham and the Hartlepool Dock & Railway at Haswell, although there was initially no connection between the lines as they were at different levels and at right angles to each other.[22][23]

The line was worked by eight stationary engines at Sunderland, Seaton, Merton, Appleton, Hetton, Moorsley, Piddington and Sherburn. Rated at between 42 and 85 horsepower (31 and 63 kW), these pulled trains using ropes up to 2,450 fathoms (14,700 ft; 4,480 m) long and between 4 and 7 1⁄4 inches (100 and 180 mm) in circumference.[24] Services started on 5 July 1836, the line was formally opened on 30 August[22] and after October[25] passengers travelled in carriages with three compartments attached to coal trains; compartments for first class were enclosed whereas those for second class passengers were open on the sides. In 1838 The railway carried over 77,000 people on trains that travelled at an average speed of 8 1⁄2 miles per hour (13.7 km/h); Whishaw (1842) reports the passenger service was unpunctual and the carriages subject to jolts whenever the trains started.[26]

Permission was granted on 30 June 1837 to divert the line in Durham south to Shincliffe, and this opened on 28 June 1839.[22] The D&SR was taken over by the York & Newcastle Railway on 1 January 1847, and became part of the York, Newcastle & Berwick Railway that year.[27]

East Coast Main Line

Great North of England Railway

On 13 October 1835 the York & North Midland Railway (Y&NMR) was formed to connect York to London by building a line from York to a junction on the planned North Midland Railway at Normanton.[28] Two weeks later the Great North of England Railway (GNER) was formed during a meeting of representatives of the York & North Midland and Stockton & Darlington Railway (S&DR).[29] Joseph Pease of the S&DR had a plan for a line north from York to Newcastle that ran over 1 1⁄2 miles (2.4 km) of the S&DR between Darlington and Croft-on-Tees.[30] To allow both sections to open at around the same time, permission for the more difficult line through the hills from Darlington to Newcastle was to be sought in 1836 and a bill for the easier line south of Darlington to York presented the following year. Pease had specified a formation wide enough for four tracks, so that freight could be carried at 30 miles per hour (48 km/h) and passengers at 60 miles per hour (97 km/h), and George Stephenson had detailed plans by November.[31]

The Act for the 34 1⁄2 miles (55.5 km) section from Newcastle to Darlington was given Royal Assent on 4 July 1836, but little work had been done by the time that the 43 miles (69 km) from Croft to York received permission on 12 July following year. In August a general meeting decided to start work on the southern section, but construction was delayed by poor labour relations with masons building the bridge over the River Tees at Croft,[32][33] and after several bridges collapsed the engineer Thomas Storey was replaced by Robert Stephenson. At York a joint GNER and Y&NMR terminus was built in the city, trains entering through a pointed arch in the city wall. On 4 January 1841 the railway opened for coal traffic using S&DR locomotives, but by the time the railway opened to passengers on 30 March its own locomotives had arrived from R & W Hawthorn.[32][33] From York, trains called at stations at

- Shipton, renamed Beningbrough in 1898

- Tollerton

- Alne

- Raskelf

- Sessay

- Thirsk

- Northallerton

- Cowton

- Croft, renamed Croft Spa in 1896

before terminating at a temporary station at Bank Top, near Darlington.[34]

In 1845 the Royal Commission's speed trials ran speed trials between York and Darlington as part of its comparison between lines built with Great Western Railway's 7 feet (2.1 m) gauge track and the 4 feet 8 1⁄2 inches (1.435 m) gauge track used by other British railways. A locomotive reached speeds of up to 60 miles per hour (97 km/h), and reached 43 1⁄4 miles per hour (69.6 km/h) hauling 80 long tons (81 t). Trials with locomotives built for the wider gauge showed them to have better performance, but the Commission recommended that new lines should be built using the more common 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in gauge track.[35]

Newcastle and Darlington Junction Railway

In 1841 it was possible to travel between Newcastle and Darlington by taking a train to Stockton, transferring by omnibus to the other railway station in the town and catching another train to Hartlepool. After changing trains at Hartlepool and at Haswell, at Sunderland an omnibus was taken across the Wear to Monkwearmouth to a Brandling Junction train to Redheugh, where the Tyne was crossed by omnibus to Newcastle.[35] There were three services a day and the journey took about six hours, about the same time as a horse and coach, but cheaper and more comfortable.[36] From November 1841 a Stockton & Darlington service was introduced between Darlington and Coxhoe, where an omnibus took passengers the 3 1⁄2 miles (5.6 km) to the Durham & Sunderland Railway at Shincliffe. This service was withdrawn in February 1842;[37] from May 1842 Newcastle could be reached in 3 1⁄4 hours via South Church station, south of Bishop Auckland, from where a four-house omnibus connected with Rainton on the Durham Junction Railway.[38]

Although the Great North of England Railway had authority for a railway from York to Newcastle, by 1841 it had spent all of the £1,330,000 of capital that had been authorised to build the line to Darlington and could not start work on the extension to Newcastle. At the time Parliament was considering the route of a railway between England and Scotland and favouring a railway via the west coast. Railway financier George Hudson chaired a meeting of representatives of north-eastern railways who wished such a railway to be built via the east coast,[39] and Robert Stephenson was engaged to select a route between Darlington and Newcastle using the existing railways as much as possible. Stephenson's proposed route differed from the GNER route slightly in the southern section before joining the Durham Junction at Rainton and using the Pontop & South Shields from Washington to Brockley Whins, where a new curve onto the Brandling Junction would allow direct access to Gateshead. This required the construction of 25 1⁄2 miles (41.0 km) of new line, 9 miles (14 km) shorter than the GNER route, but trains would need to travel 7 1⁄2 miles (12.1 km) further. However, this bypassed the S&DR, even though the railway ran parallel to the S&DR for 5 miles (8.0 km). Joseph Pease argued that it should run over its lines as this would add only 1 1⁄2 miles (2.4 km) to the route.[40] The bill was presented to Parliament in 1842, it was opposed by the S&DR and the Dean and Chapter of Durham, who were asking for £12,000 for land with the N&DJR offering only £2,400; eventually a jury valued this land at £3,500. The Newcastle and Darlington Junction Railway Act received Royal Assent on 18 June 1842, but a second Act the following year was necessary to secure the deviations from the GNER route in the south recommended by Stephenson.[38][41]

The section from Rainton to Belmont and the 2 1⁄2-mile (4.0 km) long City of Durham branch opened on 15 April 1844. The line was carried on three timber viaducts, including one 660 feet (200 m) long over the Sherburn Valley, and terminated at a new Ionic order station at Greenesfield in Gateshead. The directors travelled over the route on 24 May 1844 in advance of the official opening date of 18 June 1844,[42] when a train with nine passengers left London Euston at 5:03 am, and travelling via Rugby, Leicester, Derby, Chesterfield and Normanton, reached Gateshead at 2:24 pm. Three trains ran from Gateshead to Darlington to meet Hudson travelling on a train from York, before three locomotives hauling 39 first class carriages made a return journey over the line. Public services started the next day with rolling stock leased from the GNER; a journey from London took 12 1⁄2 hours, of which 2 3⁄4 hours was spent at stops on the way.[43][44] Intermediate stations opened on the newly built line at Aycliffe, Bradbury,[45] Ferryhill, Shincliffe, Sherburn, Belmont and Leamside.[46] Stations also opened on the Durham Junction Railway at Fencehouses and Penshaw,[46] and at Boldon on the Pontop and South Shields.[47] For three months, until the new curve opened in August, trains reversed at Brockley Whins; this was done by detaching the locomotive from a moving train about 1⁄2 mile (0.80 km) from the junction, steaming ahead past it and reversing to take the loop line to allow the still moving carriages to pass.[48][49]

Newcastle and Berwick Railway

First proposals

In the first decades of the nineteenth century, attention turned to the possibility of a railway connection between the developing railways of England, and central Scotland. The topography of the region presented obstacles: the Cheviot Hills stood in the direct line between Newcastle and Edinburgh, and a more gentle course following the low-lying coastal strip appeared to be unreasonably circuitous. Crossing the River Tyne and serving Newcastle while avoiding interference with urban areas was also difficult. Viewed from Scotland it was by no means obvious that a connection to England had to pass through Newcastle, although any western route, through Carlisle, faced equally difficult terrain in the Scottish Southern Uplands.

On 1 March 1839 plans were deposited for a Great North British Railway from Newcastle to Edinburgh. The English part of the route had been designed by George Stephenson, and the Scottish end by the established Scottish railway engineers Thomas Grainger and John Miller. The Great North British Railway did not proceed to being authorised; the money market was not amenable to financing the scheme at the time. At the Scottish end, huge public debate was generated about the route from central Scotland to what was becoming the English network. For some time it was taken for granted that only one route was viable, and numerous schemes, many of doubtful practicality, were put forward. (Some of the proposals would build a direct route across mountainous terrain, with steep gradients and prodigiously long tunnels.) A Government commission, referred to as the Smith-Barlow Commission, was set up to determine the best route, but its slow deliberation and indecisive conclusion encouraged promoters to disregard it.

George Hudson was developing the network based on the York and North Midland Railway (Y&NMR) and the Great North of England Railway, to reach Gateshead. Meanwhile, Scottish interests had decided that a line from Edinburgh to Berwick could be financed, and in 1843 a provisional North British Railway was formed. George Hudson agreed to subscribe £50,000 through the Y&NMR. He saw that if he built a line from Newcastle to Berwick, he could gain control of the North British Railway and thereby control the entire route connecting York and Edinburgh.

So was created the proposals for the Newcastle and Berwick Railway. North of Alnmouth the proposed route intersected part of the lands owned by Earl Grey; he had been Prime Minister but now was retired. He decided he would not accept the interference with his lands, and his son Viscount Howick took up the fight to protect the estate. A deviation was put forward by him to put the railway out of sight of the residence, but it would have substantially increased the cost of construction, and Stephenson, and later Hudson, attempted to negotiate acceptance of the original route.

Howick remained implacably opposed to the routing of the railway, and the promoters of the N&BR line decided to go ahead with their original route, on the basis that Parliament was now unsympathetic to obstruction of large projects beneficial to the public interest, on purely personal grounds.

When Viscount Howick became persuaded that his objections to the Newcastle and Berwick Bill in Parliament were unlikely to prevail, he instead proposed a rival line, the Northumberland Railway, which would pass clear of the estate, to the west. Isambard Kingdom Brunel was engaged to engineer the line, and he decided to adopt the atmospheric system. This involved the laying of a tube between the rails; a partial vacuum was created in the tube by static pumping stations, and each train was headed by a "piston carriage" which carried a piston running in the tube. A leather flap sealed the necessary slot in the tube before and after passage of the train. The atmospheric system avoided the weight of a locomotive and its fuel and water in the train formation, and was in use without apparent difficulty on the Dalkey Atmospheric Railway.

The relevant railways connecting with the proposed Newcastle and Berwick Railway reached Gateshead, on the south bank of the Tyne, and it was necessary to cross the Tyne by a bridge. For some time it was not clear that the bridge needed to be in Newcastle itself, but as part of the process of gaining support (and of reducing the attractiveness of Howick's Northumberland Railway) Hudson agreed on the crossing at what became the High Level Bridge and a general, "Central" station in Newcastle. These works would cost about a third of the total cost of building the railway. Some saving was made by the agreement to purchase the Newcastle and North Shields Railway, which had a Newcastle terminus at Carliol Square (close to the present-day Manors station, but immediately west of the Central Motorway viaduct) and using that company's line as far as Heaton.

Morpeth had hitherto been placed on a branch in the planned route, due to the topographical difficulties there, but as part of the matter of gaining support for the N&BR line, the route was changed to run through Morpeth, at the expense of the sharp reverse curve there. The people of Alnwick too wanted to be on the main line, but the difficulty of achieving that prevented it, and Alnwick was relegated to a branch line.

In May 1845 the House of Lords Committee considered the Newcastle and Berwick Railway proposal and the Northumberland Railway scheme. The atmospheric principle was still a proposal for use on the South Devon Railway and the fatal operational problems which caused its removal after much expenditure on that line were still in the future.

The supposed attractiveness of the Northumberland Railway scheme was weakened by its being proposed as a single line only, nonetheless costing considerably more than the double track N&BR line. Estimation of expected traffic volumes was fairly sophisticated by this time, and attention was drawn to the limited capacity to handle the anticipated demand, especially for goods trains. Moreover, the Northumberland Railway was not planning to make connections with other railways in Newcastle and Gateshead, whereas the N&BR scheme had committed to building the High Level Bridge.

During the hearings it became increasingly obvious that the Northumberland Railway Bill was going to fail, and its promoters withdrew it. The Newcastle and Berwick Railway obtained its authorising Act of Parliament on 31 July 1845,[lower-alpha 1][11][50][51]

The authorised capital was £1,400,000. Branches were included in the authorisation, to Blyth, Alnwick, Kelso, Warkworth, and adoption of the Newcastle and North Shields Railway.[52]

Constructing the N&BR

The first hurdle had been passed: the line was authorised. The Newcastle and North Shields Railway was to be acquired, so no construction was necessary from their Newcastle terminus at Carliol Square to Heaton. From there the line was to be in open country and contracts were swiftly let. However, there were several significant structures to be built on these sections, requiring viaducts at Plessey over the River Blyth, north of Morpeth over the River Wansbeck, over the River Coquet south of Warkworth, and crossing the River Aln.

Extensive use of temporary wooden structures was made to advance the date of opening of the line, while construction of the permanent structures continued underneath.

The section from Heaton Junction (on the North Shields line) to Morpeth, (14 1⁄2 miles (23.3 km)), was opened on 1 March 1847, and on 29 March the northern section from Tweedmouth (south of the Tweed near Berwick) to Chathill, (19 3⁄4-mile (31.8 km)), was opened. Four passenger trains ran each way every weekday between Newcastle and Morpeth, and between Chathill and Tweedmouth. Road coaches filled in the gaps for the time being, and a four-hour transit from Newcastle to Berwick was achieved.[50]

The central section between Morpeth and Chathill posed some engineering challenges. There was a moss at Chevington which proved difficult to build over, and a high embankment near Chevington was unstable during construction. The Board of Trade Inspecting Officer visited on 14 to 17 June 1847, but the works were still incomplete; he permitted opening on 1 July 1847 on the basis that the company would complete construction by then, and the central section duly opened on that date.[50][53][54]

More challenging was the crossing of the River Tyne and the River Tweed, and that work was to take much longer.

Newcastle and North Shields Railway

The Newcastle and Berwick Railway acquired the Newcastle and North Shields Railway (N&NSR), and used its line between the Newcastle terminus and Heaton.

The N&NSR had received the Royal Assent on 21 June 1836. The line opened on 18 June 1839, when two trains carried a total of 700 passengers on a return trip, followed by a celebration, which was interrupted by a violent thunderstorm that flooded the marquee. Public services started the next day.[55]

Its Newcastle terminus was at Carliol Square[56] on the northeast side of the city centre; the North Shields station was known as Shields at first.

In the first six months, the railway carried over 337,000 passengers. Twenty services a day were provided, taking an average of 21 minutes for the journey[57] and in 1841 the average speed of express trains was 31–34 miles per hour (50–55 km/h).[58]

In constructing the line deep valleys at the Ouse Burn and Willington Dene had to be crossed. Laminated timber arch superstructures on stone piers were used, a configuration known after its creator as the Wiebeking system. They were designed by John and Benjamin Green. The Ouseburn Viaduct consisted of five spans of 116 feet (35 m) length and 32 ft 6 in (9.9 m) rise. The Willington Viaduct had seven spans of up to 128 feet (39 m) span. The timber arches consisted of 14 layers of timber, each 22 by 3 1⁄2 inches (56 by 9 cm), held by trenails. Both structures were replaced by iron viaducts in 1869.[59]

The railway was absorbed by the Newcastle & Berwick Railway in November 1844. It was extended to Tynemouth on 29 March 1847, and independent operation continued until the line north to Morpeth opened from a junction from Heaton on 1 July 1847.[60]

The High Level Bridge

A major engineering challenge for the new company was the crossing of the River Tyne. In the period immediately prior to the authorisation of the N&BR it was by no means obvious where the crossing would be. A significant alternative was at Bill Quay, about two miles downstream from the actual High Level Bridge location, which would have left Greenesfield station, Gateshead, as the central station for the conurbation. An alternative had been a combined rail and road bridge upstream.[51]

The N&BR Act absolved the Newcastle and Darlington Junction Railway from a commitment it had earlier made to build such a bridge, on condition that the company paid the N&BR £100,000 toward the construction cost. Robert Stephenson selected the double-deck configuration to carry a roadway as well as the railway in preference to a side-by-side solution simply on the ground of the complexity of the pier foundations, as it was known that finding a hard bottom in the river was going to be difficult. A masonry structure was ruled out for similar reasons, and cast iron bowstring arches were adopted. The tied arch design eliminates thrust at the abutments and piers. To avoid a clearance problem, the road deck was suspended below the arch ribs on hangers, an idea put forward by George Leather, 1787–1870, a Leeds engineer.

Acquisition of the land required for the bridge, including the approach viaducts, amounted to £135,000, over a quarter of the cost of the bridge construction.[51]

On 11 August 1849 Captain Laffan, Inspecting Officer of the Board of Trade, inspected the bridge; there was a load test although only the eastern track had been laid. Laffan approved the bridge and the first passenger train crossed it on 15 August 1849.[11][51][61][62]

Trains had been passed across a temporary structure, as explained by Fletcher:

The first train passed along the temporary bridge used in the erection of the High Level Bridge on the 29th August, 1848, and afterwards over the magnificent arch which spans Dean Street. The last key on the High Level Bridge was driven by Mr. Hawks on 7th June, 1849; it was opened without any ceremony on August 14th, but was not brought into ordinary use until the following February.[lower-alpha 2][63]

Cook and Hoole say that the temporary structure for the High Level Bridge and the approach viaducts was opened on 1 September 1848, and that the permanent bridge opened on 15 August 1849.[64]

The railway deck was wide enough for three tracks:

The bridge is wide enough for three lines of rails on account of the width required for the roadway and footpaths underneath, but only two lines were laid on the top; afterwards a third line was added, and regularly used as a siding, with a dead-end at the Gateshead end. This was in use for many years until converted into a third running line. In an illustration by Leitch, four lines are shewn on the bridge. This shews how little an artist's sketch can be relied upon as an historical data.[63]

Crossing the River Tweed

The contract for the Tweed crossing was not let as quickly as expected, and the foundation stone was only laid on 15 May 1847. Robert Stephenson designed the structure. It has 28 arches of 61 ft 6 in (18.75 m) span, with the rails 120 feet (37 m) above the river. The viaduct is on a curve. The arches have brick soffits and the pier faces are of masonry.[59]

Although the permanent Tweed bridge had originally been scheduled for completion in July 1849, it actually first opened to goods traffic on 20 July 1850, and was formally opened on 29 August 1850.[61][65] A special arrangement was made to pass a special passenger train for visitors to a meeting at Edinburgh for the Royal Society for the Advance of Science on 1 August 1850, only a single line being available.[66]

George Leeman, Chairman of the York Newcastle and Berwick Railway, referred to the special train, and disclosed that the full opening had been intentionally delayed to comply with Royal commitments, in a speech at a dinner in honour of Robert Stephenson in Newcastle on 30 July 1850:

Gentlemen, perhaps you will think I have said enough upon the subject of the High Level Bridge. But, there is another structure, the representation of which adorns this hall, and in regard to which in a very few weeks I hope all the gentlemen I am now addressing will feel a pleasure in being present at the opening. (Applause.) Gentlemen, you are aware that the bridge for the passage of the trains of the Company over [the permanent bridge across] the Tweed has not been opened until the last few days, and then only for one line across the bridge. We have opened the bridge thus far at the present time for the purpose of enabling those travelling to the great meeting of the British Association at Edinburgh to pass over it rather than over the temporary structure that had been used previously. You will ask why we have delayed the laying of the second line and the complete opening of the bridge? We have done so because we considered it an undertaking of such a character that it should receive its finishing stroke from one of the highest in the land. We were anxious to celebrate the opening of the bridge by the presence of one of the most distinguished patrons of science and art in this country, Prince Albert. (Applause.) We have been in communication with his Royal Highness, and we had hoped to have been able to open the bridge at an earlier period than that at which we are now assembled; but, gentlemen, though that has not been done, I am happy to say our hopes in other respects are not only realized, but that they have been exceeded ... The announcement I am enabled to make is that not only will his Royal Highness give his own presence on that auspicious occasion, but that her Majesty the Queen will do so likewise. (Loud and continued cheering.)[67]

Fletcher recorded slightly different opening dates:

The first train passed along the temporary bridge used on the erection of the High Level Bridge on the 29th August 1848 ... The last key on [the permanent structure of] the High Level Bridge was driven by Mr. Hawks on 7th June, 1849; it was opened without any ceremony on August 14th, but it was not brought into ordinary use until the following February [1850] ... [There was a formal opening later:] London was connected with Edinburgh through Newcastle and Berwick, when Queen Victoria opened (29th August 1850) the bridges over the Tyne and Tweed, and the Central station, Newcastle.[63]

Cook and Hoole have different dates for the temporary bridge: it opened on 10 October 1848, and the permanent bridge on 20 July 1850 for goods trains and 29 August 1850 for passenger trains.[64] Wells says the temporary bridge opened in October 1848.[62]

In opening the Tweed bridge at Berwick, Queen Victoria named it The Royal Border Bridge.

Newcastle Central station

By the time the Newcastle and Berwick Railway was authorised, Hudson had decided that a central station in Newcastle was essential. At this time too, the Newcastle and Carlisle Railway had come to terms with the fact that its alternative schemes were not to be progressed, so the central station would be jointly occupied by that company. The Newcastle and Darlington Junction Railway board and the city authorities of Newcastle were consulted and gave their approval to the curved station site fronting Neville Street. Little through running between the N&CR and the other liens was expected, and trains from the N&DJR running forward on the N&BR would reverse in the station, so the majority of the platforming was designed as bays, with only one through platform. Carriage stabling sidings were to be located on the south side.

The station buildings were designed by John Dobson; tenders were let for the construction on 7 August 1847. The trainshed consisted of three spans with curved wrought iron ribs supporting the roof: the first to be designed and built in Britain on this arrangement. A novel arrangement of rolling the wrought iron plates without excessive wastage due to the curvature of the webs was employed.[51]

The frontage to Neville Street was "a remarkably grandiloquent composition with two covered carriage drives meeting in an enormous porte-cochere, which also housed a central, processional carriage route on the axis of the main entrance".[51] In fact work on it was suspended in May 1849 and only resumed early in the following year, and due to financial strictures, some simplification was carried out, including abandonment of the portico. (This was provided in 1863.)

The station was formally opened by Queen Victoria on 29 August 1850 and the following day York, Newcastle and Berwick Railway[lower-alpha 3] trains were diverted to the new station; Greenesfield station in Gateshead closed to passengers.[lower-alpha 4][51][68][66]

North British Railway

Berwick was of course not Hudson's ultimate objective in promoting the Newcastle and Berwick Railway. The North British Railway from Edinburgh to Berwick (later known as Berwick-upon-Tweed) had been promoted in 1843. Hudson arranged to subscribe £50,000 through the Y&NMR. He saw that this enabled him to make a line connecting Normanton, York and Edinburgh under his control.

The North British Railway had been subject to the frenzy of proposed schemes linking central Scotland with the developing English network and the Smith-Barlow Commission, referred to above. In fact a race was in progress to be the first railway to offer a through service to London from Edinburgh and Glasgow, and the North British Railway had an effective rival in the Caledonian Railway. However at the crucial time for presenting a Parliamentary Bill, the Caledonian was unable to generate sufficient subscriptions, and had to delay a year to the following session, giving the North British a lead. Nonetheless the Caledonian Railway reached Carlisle and served both Edinburgh and Glasgow. The rivalry between the two companies was to be bitter and enduring.

The North British Railway opened its main line between Edinburgh and Berwick on 22 June 1846.[69]

Opening of the Newcastle and Berwick Railway

As has been described, the section of line from Heaton Junction (on the North Shields line) to Morpeth, (14 1⁄2 miles (23.3 km)), was opened on 1 March 1847, and on 29 March the northern section from Tweedmouth (south of the Tweed near Berwick) to Chathill, (19 3⁄4-mile (31.8 km)), was opened. The central section between Morpeth and Chathill was not opened until 1 July 1847.[53]

Although the two major river crossings (of the Tyne and the Tweed) were unbridged, in October 1847 a "through service" was advertised between Edinburgh and London via Berwick, Newcastle, York, Normanton and Rugby, taking 13 hours and 10 minutes. Passengers walked, or were conveyed by coach, across the two river crossings for the time being.[69]

The Newcastle station was (until the opening of Central station) the N&NS station at Carliol Square. Early stations were Manors (opened 1848), Heaton (N&NS station), Killingworth, Cramlington, Netherton, Morpeth, Longhirst, Widdrington, Acklington, Warkworth, Lesbury, Longhoughton, , Christon Bank, Chathill, Lucker, Belford, Beal, Scremerston and Tweedmouth.[66][70] The Blyth, Wansbeck, Coquet and Aln rivers were crossed by timber viaducts; they were later rebuilt in masonry.

First branches

The Newcastle and Berwick Railway had obtained authorisation for a Kelso branch. It was to run from Tweedmouth, immediately south of the River Tweed near Berwick, to Kelso but strenuous objections from the Duke of Roxburghe prevented the intended approach to the town, and the terminus was at Sprouston, 4 miles (6 km) short, instead.

Contracts were let in 1847. There were four significant viaducts on the line. The one over the River Till, ten miles from Tweedmouth, was incomplete at the time of the inspection by Captain H. G. Wynne, the Board of Trade Inspecting Officer, but he agreed to opening over a single line at very limited speed. The line opened from a junction at Tweedmouth to Sprouston, some distance short of Kelso, on 27 July 1849. On 1 June 1851 the line was extended to Mellendene Farm, about halfway from Sprouston to Kelso, joining end on with the North British Railway branch there, although the NBR trains did not extend east of Kelso itself. Even now the Kelso station was inconveniently located south of the Tweed there, due to the Duke of Roxburghe's opposition.

A through route existed from Tweedmouth to St Boswells on what became the Waverley Route and through running was originally contemplated. However except for a Sunday train in the twentieth century, this was never done, and indeed the timetables east and west of Kelso were not coordinated so that no useful connection for passengers was available there. The Tweedmouth junction faced south, so that Berwick to Kelso trains had to reverse there.[71][72]

Alnwick was the most important town in the vicinity, and it was desired to bring the main line through the town, but the terrain made that impracticable. On the first opening of the main line there was a "Lesbury" station, close to the present-day Alnmouth, but a branch line from there had been authorised in the original Act of Parliament. It duly opened for goods trains on 19 August 1850; passenger trains started running on 1 October 1850. There were no intermediate stations on the branch.[62][64][66]

A branch to Amble was also authorised; there was an important harbour there (known as Warkworth) and a colliery at Broomhill nearby. A branch ran from Amble Junction, near Chevington, through Broomhill to Amble and the harbour, opening for mineral traffic, always the dominant business, on 5 September 1849. The line was doubled between Broomhill and Warkworth. Passenger traffic was considerably delayed, starting on 2 June 1879, with stations at Broomhill and Amble. (Warkworth station had always been on the main line.)

The passenger business was always thin, and it was withdrawn on 7 July 1930. Mineral traffic continued but declined after World War II and the line closed on 14 December 1964.[62][64][66]

A branch to Blyth was authorised in the N&BR Act of Parliament, but this was not proceeded with. The Blyth and Tyne Railway had a connection there.[73]

Amalgamations

During the railway mania of the mid-1840s many people invested in railway companies, believing it a means of quickly getting rich. In the three years between 1844 and 1846 Parliament passed 438 Acts giving permission for over 8,000 miles (13,000 km) of line, many in direct competition with existing railways.[74] Hudson was brought up in a farming community and started adult life as a draper's assistant in York. In 1827, when he was 27 years old, he inherited £30,000. He had no former interest in railways, but seeing them as a profitable investment, he formed the York & North Midland Railway in 1835;[75] by the mid-1840s he was also chairman of the Midland Railway, Newcastle & Berwick and Newcastle & Darlington Junction Railways. Called the "Railway King" by the preacher Sydney Smith, he was said to have the favour of Albert, the Prince Consort. So as to better promote the bills submitted by the railway companies he controlled, Hudson successfully stood as a Conservative Member of Parliament for Sunderland in 1845.[76]

Hudson bought the railway companies over which the N&DJR ran to Newcastle; the Durham Junction was purchased in 1843 and the Brandling Junction the following year[77] and he arranged to buy the Pontop and South Shields and Durham & Sunderland railways, although these were not absorbed until 1847.[78] Hudson was concerned with the progress of the Great Northern Railway, that was building a railway north from London; if it succeeded in linking up with the Great North of England Railway at York, traffic between England and Scotland would be diverted from the Y&NMR, to his detriment. In 1845 Hudson made a generous offer to lease the GNER and buy it within five years, and that year GNER shares increased in value by 44 per cent as the N&DJR took over operations on 1 July 1845. On 27 July 1846 the N&DJR changed its name to the York and Newcastle Railway and on 9 August 1847, less than a year later, merging with the Newcastle and Berwick Railway. The combined company was named the York, Newcastle and Berwick Railway.[79]

At the end of 1848 the dividend paid by the YN&BR dropped from nine per cent to six per cent and at the subsequent half-yearly shareholders meeting the very high cost of certain GNER shares bought during the merger was questioned. The company had purchased them from Hudson; an investigating committee was set up and as improper dealings were revealed, Hudson resigned as chairman in May 1849. The committee reported on a number of irregularities in the account, such as inflating traffic figures and charging capital items to the revenue account, thus paying dividends out of capital.[80][81] No dividend was paid for the first half year of 1849, and Hudson was to pay £212,000 settling claims over share transactions.[82] The company was unable to complete the purchase of the GNER when this became due in July 1850, and agreement was reached to pay in three instalments over six years.[83]

Operations

Services

Early railway steam locomotives had no brakes, although some tenders were fitted with them,[84] and there were no weatherboards, the driver and firemen wearing moleskin suits for protection.[85] The YN&BR absorbed the locomotives of the earlier companies and established a locomotive works at Gateshead; those of the Brandling Junction, Newcastle and North Shields and Great North of England railways had six wheels, with two, four or six driven.[86][87] Purpose built railway carriages began to be used from 1834, replacing the stage coaches that had been converted for railway use.[88] Luggage and sometimes the guard travelled on the carriage roof;[85] a passenger travelling third class suffered serious injuries after falling from the roof on the Stockton and Darlington Railway in 1840.[89] Carriages were lit by oil lamps, smoking was banned by all the early railways[lower-alpha 5] and third class and many second class compartments had no upholstery.[90][91] Mixed trains, passenger carriages coupled together with mineral and goods wagons, were common; coal was carried in chaldron wagons[lower-alpha 6] and goods on low sided trucks.[94]

When the Great North of England Railway opened in 1841, the fastest train between York and Darlington was the London Mail. Connecting at York with a service that had travelled overnight from London, this travelled the 44 miles (71 km) to Darlington in 2 hours 5 minutes, an average speed of 21 miles per hour (34 km/h). By 1854, when the North Eastern Railway was formed, express trains were travelling between York and Berwick at about 40 miles per hour (64 km/h).[95]

A system of red and white flags on poles was used to signal to engine drivers where the Brandling and Stanhope & Tyne railways crossed at Brockley Whins; a white flag meant a Brandling Junction train could proceed and a red was hoisted for a Stanhope and Tyne train. Lamps with coloured light were used at night. Discs were connected to the points at the ends of the Newcastle and North Shields Railway line to show drivers their position.[96] Originally paper tickets were written out by the clerk in a time-consuming process, so some railways, such as the Brandling Junction Railway, closed the station doors five minutes before trains were due to depart.[97] With such as system it was difficult to keep accurate records, and Thomas Edmondson, a Newcastle and Carlisle Railway station master printed numbered card tickets, which were dated by a press first used in 1837. The GNER issued such tickets from 1841.[98] The electric telegraph was installed in 1846–47 on the York & Newcastle and Newcastle & Berwick railways.[99]

New lines

A railway between Leeds and Thirsk was proposed in 1844, and on 21 July 1845 the Leeds & Thirsk Railway obtained permission for a railway that connected Leeds directly with the GNER at Thirsk. The company wished to reach the Stockton & Hartlepool Railway at Billingham via a line that crossed under the GNER's line at Northallerton.[100] Hudson argued for a route using the lines of the Great North of England, Newcastle & Darlington Junction and the Hartlepool Dock & Railway, but in the second Leeds & Thirsk Act, given Royal Assent on 1846, the L&TR was given permission to build a line from Northallerton and only required to run over the GNER between Thirsk and Northallerton.[101] Freight trains started running between Ripon and Thirsk on 5 January 1848 before the line was formally opened on 31 May 1848, public traffic starting the next day. Trains started running through to a temporary terminus in Leeds in July 1849.[102] The Leeds & Thirsk Railway received permission to change its name to the Leeds Northern Railway on 3 July 1851,[103][lower-alpha 7] and on 22 July 1848 a direct route to Stockton passing under what was now the YN&BR at Northallerton was authorised, this opening on 2 June 1852.[104][105]

The GNER had applied for a branch line to Richmond in 1844, but it was the York & Newcastle that opened the 9 3⁄4-mile (15.7 km) branch with three intermediate stations on 10 September 1846. The GNER had also been given permission for three more branches in 1846; a branch from Pilmoor to Boroughbridge opened on 17 June 1847 and one from Northallerton to Bedale in 1848. Permission for a line to Malton was given in 1846 to the GNER, altered in 1847 by the York & Newcastle, and again in 1848 by the York, Newcastle & Berwick before this single track branch opened on 19 May 1853.[106] The East & West Yorkshire Junction Railway had been authorised on 16 July 1846 for a line from the former GNER main line just outside York to Knaresborough. The line was initially worked by the York, Newcastle & Berwick Railway when it opened to a temporary station at Hay Park Lane on 30 October 1848, the line was then worked by E.B. Wilson & Company, before the railway was absorbed by the York & North Midland on 1 July 1851.[107][108]

On the main line a direct line from Washington to Pelaw avoiding Brockley Whins was authorised in 1845 and opened 1 September 1849.[21] From 15 August 1849 trains crossed the high level bridge in Newcastle, which was formally opened by Queen Victoria on 28 September.[109] On 8 August 1850 the first through GNR train from London arrived at York, having started at a temporary station at Maiden Lane.[lower-alpha 8][111] Work started in 1847 on the Royal Border Bridge, a 28 arch 2,160 feet (660 m) long viaduct engineered by Robert Stevenson, to cross the Tweed Valley that stood between the N&BR at Tweedmouth and the North British Railway at Berwick. Freight trains crossed the bridge from 28 July 1850 and the structure was opened formally by Queen Victoria on 29 August 1850, the day she opened the station at Newcastle Central.[109]

The N&DJR had been given permission in 1846 for a line from Penshaw, on the main line just south of Washington, to a station in Fawcett Street in Sunderland. The line opened to freight on 20 February 1852 and passengers were carried after 1 June 1853. Authority for line through the Team Valley to Bishop Auckland was given to the YN&BR in 1848, but work did not start following Hudson's departure the following year.[112]

Locomotives

- Locomotive list

- Notes

- Running numbers are those applied by the North Eastern Railway. Numbers applied by the York, Newcastle and Berwick Railway are unknown

- Running number order is not always consistent with dates. It is likely that numbers of withdrawn locomotives were re-used on new locomotives

Accidents and incidents

On 2 February 1850, the firebox of a locomotive collapsed whilst it was hauling a freight train near Darlington. Two people were killed.[114]

North Eastern Railway

In 1852 the Leeds Northern Railway reached Stockton, made an alliance with the YN&BR's competitors and a price war broke out, the fare for the 238 miles (383 km) between Leeds and Newcastle dropping to two shillings.[lower-alpha 9] Harrison, who had become General Manager and Engineer of the YN&BR, favoured merger with LNR and Y&NMR as the route to peace, and he was able to show his own board the increased profit that amalgamation had brought the YN&BR. The agreement of the boards of the three railway companies was reached in November 1852 that the shares of the three companies remain separate but replaced by Berwick Capital Stock, York Capital Stock and Leeds Capital Stock, with dividends paid from pooled revenue. However, the deal was rejected by the shareholders of the Leeds Northern, who felt their seven per cent share of revenue too low and joint operation was agreed instead of merger with Harrison appointed General Manager. The benefits of this joint working allowed Harrison to raise the offer to the Leeds Northern shareholders, and by Royal Assent on 31 July 1854 the three companies merged to form the North Eastern Railway; with 703 route miles (1,131 km) of line, becoming the largest railway company in the country.[116]

The line through the Team Valley that had been planned in 1846 was built to link from the main line south of Leamside station to Bishop Auckland.[lower-alpha 10] An 80-foot (24 m) deep cutting was dug at Neville's Cross and two timber and three stone viaducts were built, one with eleven arches through west of the City of Durham; passenger trains ran over the line from 1857.[117][118] North of Durham, a line from Gateshead through Chester-le-Street to a junction at Newton Hall opened in 1868. From 1872 this became the new main line after a line opened from Tursdale Junction the N&DJR to this branch at Relly Mill, south of the Durham Viaduct.[119] In 1877 a new station opened at Haswell, connecting the former Durham & Sunderland and Hartlepool Docks & Railway lines,[120] and at York a through station outside the city walls replaced the old terminus that had required trains to reverse before continuing.[121] In 1879 a bridge opened over the Wear, allowing access from the former Brandling Junction Railway to a new central station in Sunderland.[122]

The former Newcastle & North Shields Railway line, together with later extensions through Tynemouth and the Riverside branch, was electrified in 1903, and passengers carried on the new trains from 1904.[123] The Londonderry, Seaham & Sunderland Railway, which had opened along the coast in 1854, was taken over by the NER in 1900 and extended to Hart, 3 1⁄4 miles (5.2 km) from Hartlepool on the former Hartlepool Docks & Railway line; the new coast line opened in 1905.[124] The King Edward VII Bridge opened in 1906 allowing east coast main line trains access to the station from the west, so they no longer needed to reverse at Newcastle station.[125]

As a result of the Railways Act 1921, on 1 January 1923 the North Eastern Railway became part of the London and North Eastern Railway (LNER). Britain's railways were nationalised on 1 January 1948 and the former York, Newcastle & Berwick lines were placed under the control of British Railways.[126]

Legacy

Today's East Coast Main Line is an electric high-speed railway that between York and Berwick follows, for the most part, the original route of the York, Newcastle & Berwick Railway. Between York and Northallerton there are a pair of fast lines with a speed limit of 125 miles per hour (201 km/h) and a pair of slow lines that are limited to 70–90 miles per hour (110–140 km/h). Passenger services over the former Leeds Northern Railway line through Harrogate to Northallerton were withdrawn in 1967,[127] but the line north to Stockton remains.[128][129] The branch to Boroughbridge, extended to Knaresborough in 1875, closed to passengers in 1950 and completely in 1964 when the goods service was withdrawn. Services to Malton terminated at Gilling from 1931, and services were withdrawn completely in 1953. The Bedale branch, extended to Leyburn in 1856 and to Hawes in 1878, closed to passengers in 1954 and completely in 1964.[130] Only Northallerton and Thirsk stations remain open between York and Darlington,[131] Eryholme having closed in 1911 and the rest in 1958, except for Croft Spa that was served by Richmond branch trains until this closed in 1969.[132]

North of Darlington line speeds are between 75 and 115 miles per hour (121 and 185 km/h) on a two track railway[133] that follows the N&DJR route until Tursdale Junction, where trains now take the Team Valley line to Newcastle. The old main line, the Leamside Line to Pelaw, has been closed since the present main line was electrified in 1991, but Network Rail are considering reopening the line as a diversionary route for freight.[129] Regular passenger services on the line built by the D&SR terminated at Pittington from 1931 and were withdrawn between Sunderland and Pittington in 1953, passenger trains over the line between Hartlepool and Haswell having been withdrawn the previous year. The Penshaw branch to Sunderland closed to passengers in 1964.[122] The former BJR line to Sunderland remains open, with services running through Sunderland on to Hartlepool via the coast line.[131][134] The passenger service over the former Pontop & South Shields Railway line was withdrawn in 1955[135] and the heritage Tanfield Railway runs over the Tanfield branch, this having closed in 1964.[136][137]

Diesel multiple units replaced the electric trains on the former Newcastle & North Shields Railway line between 1967[123] and 1980, when Tyne & Wear Metro opened via Benton; the line was closed for reconstruction until 1982, reopening with electric units between Walkergate and Tynemouth.[138] North of Newcastle the line follows the formation built by the Newcastle & Berwick Railway; speeds over this two track line are limited to 110 to 125 miles per hour (177 to 201 km/h).[139] The line to Kelso closed in 1965, the Alnwick branch in 1968 and the Amble branch in 1969.[140]

In 1888 it took 8 1⁄2 hours to travel from London to Edinburgh; this schedule was reduced by fifteen minutes after trains included restaurant carriages and the stop to allow passengers to eat en route was no longer necessary. When the Coronation Express started in 1937 it took 6 hours to travel from London to Edinburgh.[95] Today, trains cover the distance in under 4 1⁄2 hours, with the 05:40 'Flying Scotsman' service taking exactly 4 hours, between Edinburgh and Kings Cross, making only 1 stop at Newcastle.[141]

See also

- York, Newcastle & Berwick, York & North Midland, Leeds Northern map Map of the system in 1854

Notes

- Hoole page 203; Carter says 13 July but that must be a mistake; the London Evening Standard forecast this in the previous day's edition: "The royal assent will be given by commission in the House of Lords to-morrow afternoon at half past four o'clock to the following sixty bills, which have passed both houses ... the Newcastle and Berwick Railway Bill ..." While there is no reason whatever to think that this did not take place, no newspaper report seems to be available recording that the royal assent was indeed given. Carter says 13 July but that is an error. Addyman is silent on the date in The Newcastle and Berwick Railway, giving only (on page 25) that a certain event on 17 July 1845 was "less than two weeks before the N&B Act was passed", but is forthright on page 36 of The High Level Bridge. Freeman's Journal of Friday 1 August 1845 simply reprinted the previous week's forecast from other periodicals, still stating that the royal assent would be given "to-morrow (Thursday)": this is obviously completely misleading.

- This is a remarkably long delay before taking revenue from such an expensive structure; Fletcher does not explain it or refer to it, and it may be suspected that this is an error by him.

- The Newcastle and Darlington Junction Railway and the Newcastle and Berwick Railway had merged to form the York, Newcastle and Berwick Railway on 9 August 1847.

- Tomlinson (page 506) says 1 January 1851, but this may be a mistake. Quick agrees 30 August 1850 and adds that the "through service to the south started 1 September 1848, trains reversing short of the site of Central, still under construction, and using temporary bridge across Tyne; permanent bridge opened 15 August 1849, still with reversal short of Central site."

- Smoking was universally permitted in designated compartments after the Regulation of Railways Act 1868 required such accommodation to be provided.[90]

- These wagons were designed to carry a Newcastle chaldron (pronounced chalder in Newcastle) of coal, about 53 long cwt (5,900 lb; 2,700 kg). This differed from the London chaldron, which was 36 bushels or 25 1⁄2 long cwt (2,860 lb; 1,300 kg).[92][93]

- Sources differ on the date of this name change: Awdry (1990, p. 143) states 3 July 1851 and Tomlinson (1915, p. 511) states 8 August 1851, whereas Allen (1974, p. 100) says this happened in 1849.

- London King's Cross opened two years later on 14 October 1852.[110]

- Two shillings in 1852 was worth about £10.95 today.[115]

- Allen (1974, p. 108) mention this was designed as an extension of the former Durham & Sunderland Railway line. Hoole (1974, p. 167) states that according to Tomlinson (1915) the line was such an extension, but the archives at York show the line to have been planned separate from the D&SR, leaving the old main line at Sherburn.

References

- Allen 1974, pp. 10–11.

- Hoole 1974, pp. 188–189.

- Allen 1974, pp. 42–43.

- Hoole 1974, p. 188.

- Hoole 1974, pp. 188–190.

- Tomlinson 1915, pp. 392–393.

- Tomlinson 1915, pp. 332–333, 366–367.

- Allen 1974, p. 80.

- Allen 1974, p. 91.

- Cobb 2006, pp. 476–478.

- K Hoole, A Regional History of the Railways of Great Britain: Volume IV: The North East, David & Charles, Dawlish, ISBN 0-7153-6439-1

- Allen 1974, pp. 47–48.

- Allen 1974, p. 67.

- Awdry 1990, p. 135.

- Allen 1974, pp. 101–102.

- Hoole 1974, p. 164.

- Allen 1974, p. 44.

- Whishaw 1842, p. 72.

- Tomlinson 1915, pp. 332–333.

- Allen 1974, pp. 71, 75.

- Hoole 1974, p. 161.

- Hoole 1974, p. 151.

- Whishaw 1842, p. 75.

- Whishaw 1842, pp. 76–77.

- Allen 1974, p. 45.

- Whishaw 1842, pp. 74, 77–78.

- Allen 1974, pp. 90–91.

- Allen 1974, p. 59.

- Allen 1974, p. 64.

- Tomlinson 1915, p. 278.

- Allen 1974, pp. 64–65.

- Hoole 1974, pp. 93–94.

- Allen 1974, pp. 67–69.

- Hoole 1974, p. 95.

- Allen 1974, p. 70.

- Tomlinson 1915, p. 430.

- Hoole 1974, p. 165.

- Allen 1974, p. 74.

- Allen 1974, pp. 67, 71.

- Allen 1974, pp. 71–72.

- Tomlinson 1915, p. 439.

- http://twsitelines.info/SMR/4374

- Allen 1974, pp. 76–78.

- Hoole 1974, pp. 162–163.

- Cobb 2006, p. 448.

- Cobb 2006, p. 460.

- Cobb 2006, p. 477.

- Tomlinson 1915, p. 416.

- Allen 1974, pp. 79–80.

- John F Addyman (editor), A History of the Newcastle & Berwick Railway, North Eastern Railway Association, 2011, ISBN 978-1-873513-75-0

- John Addyman and Bill Fawcett, The High Level Bridge and Newcastle Central Station, North Eastern Railway Association, 1999, ISBN 1-873513-28-3

- E F Carter, An Historical Geography of the Railways of the British Isles, Cassell, London, 1959

- Tomlinson, pages 482–483

- https://communities.northumberland.gov.uk/007127FS.htm

- Allen 1974, p. 81 and 82.

- https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-tyne-27503634

- Whishaw 1842, pp. 358–359.

- Tomlinson 1915, p. 396.

- M F Barbey, Civil Engineering Heritage: Northern England, Thomas Telford Publishing, London, 1981, ISBN 0-7277-0357-9

- Allen 1974, pp. 82–86.

- John Thomas, The North British Railway, volume 1, David & Charles, Newton Abbot, 1969, ISBN 0-7153-4697-0, page 48

- J A Wells, The Railways of Northumberland and Newcastle upon Tyne between 1828 and 1998, Powdene Publicity Limited, Newcastle upon Tyne, 1998, ISBN 0-9520226-2-1

- James Richard Fletcher, The Development of the Railway System in Northumberland and Durham, Address to the Newcastle-on-Tyne Association of Students of the Institution of Civil Engineers, 1902

- R A Cooke and K Hoole, North Eastern Railway Historical Maps, Railway and Canal Historical Society, Mold, 1975 revised 1991, ISBN 0-901461-13-X

- The Architect (periodical), 7 September 1850, quoted in Tomlinson, page 507

- M E Quick, Railway Passenger Stations in England Scotland and Wales—A Chronology, The Railway and Canal Historical Society, 2002

- Newcastle Journal, 3 August 1850

- Tomlinson, page 506

- David Ross, The North British Railway: A History, Stenlake Publishing Limited, Catrine, 2014, ISBN 978-1-84033-647-4

- Cobb, 2006

- Christopher Dean, The Kelso Branch, in Addyman

- Roger Darsley and Dennis Lovett, Berwick to St Boswells via Kelso including the Jedburgh Branch, Middleton Press, Midhurst, 2015, ISBN 978-1-908174-75-8

- J A Wells, The Blyth and Tyne Railway, Northumberland County Library, 1989, ISBN 0-9513027-4-4

- Allen 1974, pp. 88, 98.

- Allen 1974, pp. 58–59.

- Allen 1974, p. 89.

- Allen 1974, pp. 75, 78.

- Allen 1974, pp. 80, 91.

- Allen 1974, p. 90.

- Allen 1974, p. 96.

- Tomlinson 1915, pp. 493–494, 498.

- Allen 1974, p. 97.

- Tomlinson 1915, p. 501.

- Tomlinson 1915, p. 398.

- Tomlinson 1915, p. 423.

- Tomlinson 1915, p. 394.

- Allen 1974, p. 187.

- Tomlinson 1915, p. 399.

- Tomlinson 1915, p. 400.

- Allen 1974, p. 207.

- Tomlinson 1915, p. 425.

- Griffiths, Bill (2005). A Dictionary of North East Dialect. Northumbria University Press. p. 30. ISBN 978-1-904794-16-5.

- Tomlinson 1915, p. 120.

- Tomlinson 1915, p. 404.

- Allen 1974, pp. 213–215.

- Tomlinson 1915, p. 411.

- Tomlinson 1915, pp. 418, 421.

- Tomlinson 1915, pp. 421–422.

- Tomlinson 1915, p. 532.

- Hoole 1974, p. 100.

- Allen 1974, pp. 91–92.

- Hoole 1974, pp. 100–101.

- The Statutes of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. George Eyre and Andrew Strahan. 1851. p. 844. Retrieved 16 November 2013.

- Allen 1974, p. 103.

- Hoole 1974, p. 101.

- Hoole 1974, pp. 109–111.

- Awdry 1990, p. 143.

- Allen 1974, p. 100.

- Allen 1974, pp. 85–86.

- Butt 1995, p. 134.

- Allen 1974, p. 94.

- Hoole 1974, p. 167.

- http://www.steamindex.com/locotype/nerloco.htm

- Hewison 1983, pp. 31–32.

- UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- Allen 1974, pp. 105–107.

- Allen 1974, pp. 108–109.

- Hoole 1974, pp. 166–167.

- Hoole 1974, pp. 15, 166–167.

- Cobb 2006, p. 478.

- Allen 1974, p. 154.

- Hoole 1974, p. 154.

- Hoole 1974, pp. 212–214.

- Allen 1974, p. 182.

- Hoole 1974, p. 205.

- Hedges 1981, pp. 88, 113–114.

- Hoole 1974, p. 106.

- Network Rail 2012, pp. 39–41.

- Shannon, Paul (October 2013). "Fitting in freight". Modern Railways. pp. 60–63.

- Hoole 1974, pp. 109–112.

- "Timetable Map" (PDF). National Rail. 2013.

- Hoole 1974, pp. 95, 108.

- Network Rail 2012, pp. 43–44.

- Table 44 National Rail timetable, May 13

- Hoole 1974, pp. 102–103.

- Hoole 1974, p. 200.

- "Welcome to the World's Oldest Railway". Tanfield Railway. Retrieved 29 September 2013.

- Hoole 1986, pp. 106–112.

- Network Rail 2012, pp. 47–48.

- Cobb 2006, pp. 502, 514, 524.

- Table 26 National Rail timetable, May 13

Sources

- Awdry, Christopher (1990). Encyclopaedia of British Railway Companies. Patrick Stephens. ISBN 1-85260-049-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Allen, Cecil J. (1974) [1964]. The North Eastern Railway. Ian Allan. ISBN 0-7110-0495-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Butt, R.V.J. (1995). The Directory of Railway Stations. Yeovil: Patrick Stephens Ltd. ISBN 1-85260-508-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cobb, Colonel M.H. (2006). The Railways of Great Britain: A Historical Atlas. Ian Allan. ISBN 978-0-7110-3236-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hedges, Martin, ed. (1981). 150 years of British Railways. Hamyln. ISBN 0-600-37655-9.

- Hoole, K. (1986). Rail Centres: Newcastle. Littlehampton Book Services. ISBN 0-7110-1592-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hoole, K. (1974). A Regional History of the Railways of Great Britain: Volume IV The North East. David & Charles. ISBN 0-7153-6439-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tomlinson, William Weaver (1915). The North Eastern Railway: Its rise and development. Andrew Reid and Company.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Whishaw, Francis (1842). The Railways of Great Britain and Ireland Practically Described and Illustrated (2nd ed.). London: John Weale. OCLC 833076248.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Route Specifications – London North Eastern. Network Rail. 2012. Retrieved 28 September 2013.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to York, Newcastle and Berwick Railway. |

- York, Newcastle and Berwick Railway Company The National Archives