King Edward VII Bridge

The King Edward VII Bridge spans the River Tyne between Newcastle upon Tyne and Gateshead, in North East England. The railway bridge is a Grade II listed structure.[1] It has been described as "Britain’s last great railway bridge".[2]

King Edward VII Bridge | |

|---|---|

King Edward VII Bridge, in 2015 | |

| Coordinates | 54.9632°N 1.6162°W |

| OS grid reference | |

| Carries | East Coast Main Line |

| Crosses | River Tyne |

| Locale | Tyneside |

| Owner | Network Rail |

| Maintained by | Network Rail |

| Heritage status | Grade II listed |

| Network Rail Bridge ID | ECM5-259 |

| Preceded by | Redheugh Bridge |

| Followed by | Queen Elizabeth II Bridge |

| Characteristics | |

| Design | Truss bridge |

| Material | Steel |

| Pier construction | |

| Total length | 350.8 m (1,151 ft) |

| Width | 15.3 m (50 ft) |

| No. of spans | 4 |

| Clearance below | 25.3 m (83 ft) |

| Rail characteristics | |

| No. of tracks | 4 |

| Track gauge | 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in) |

| Electrified | 25 kV 50 Hz AC |

| History | |

| Designer | Charles A. Harrison |

| Engineering design by | Charles A. Harrison |

| Constructed by | Cleveland Bridge & Engineering Company |

| Construction start | 29 July 1902 |

| Opened | 1 October 1906 |

| Inaugurated |

|

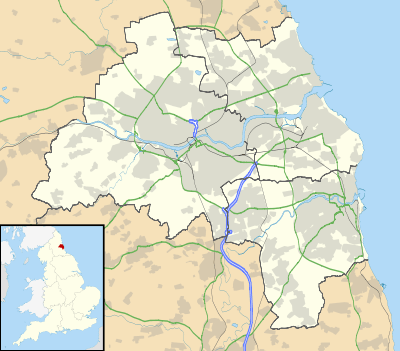

King Edward VII Bridge Location in Tyne and Wear | |

| Railways between Newcastle and Gateshead | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The bridge was designed and engineered by Charles A. Harrison, the Chief Civil Engineer of the North Eastern Railway, and built by the Cleveland Bridge & Engineering Company. The bridge has four lattice steel spans resting on concrete piers. Its length is 1,150 ft (350 m) and it is 112 ft (34 m) above high water mark. It cost more than £500,000.[3]

The bridge was opened by King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra on 10 July 1906, despite being unfinished. General traffic began using it on 1 October 1906.[4] Before it was completed, trains used the older High Level Bridge to reach Newcastle railway station and had to reverse out of the station. The bridge added four railway tracks and a direct line through the station easing congestion.

History

Background

In 1849, the High Level Bridge, a twin-deck railway and road bridge allowing traffic to cross the River Tyne, was opened by Queen Victoria. Trains could then reach Newcastle railway station but had to depart back across the High Level Bridge by reversing out of the station.[2]

Over the following 50 years, the railway network and the number of passengers had expanded greatly.[2] By the 1890s, the volume of traffic crossing the High Level Bridge, 800 train and light engine movements daily, was major concern of the NER, who operated services across it. It was clear that a second railway bridge over the Tyne was needed.[2][5]

Options included building a bridge between Dunston and Elswick or Heaton and Pelaw, or widening the High Level Bridge to six tracks. By 1898, the company decided to build another bridge on the present site and plans were revealed in the Evening Chronicle.[2] On 9 August 1899, the updated North Eastern Railway Act, which included the railway bridge over the Tyne, received royal assent.[5]

The new bridge was a design by Charles Harrison, chief engineer of the NER. He was the nephew of Thomas Harrison who with Robert Stephenson had produced plans for the High Level Bridge.[4] Early designs were for a two-span bridge supported by girder lattices, that would join with several land approach arches. It was redesigned when abandoned coal workings were discovered at both ends.[3]

The revised design was a lattice girder bridge carrying four tracks with four spans over the river.[3][5] The spans were supported by five sandstone piers decorated with pairs of cutaway arches, three of which are in the river. The northern approach has ten arches which housed workshops.[3]

Construction

.jpg)

On 13 February 1902, the bridge contract was awarded to Darlington-based Cleveland Bridge & Engineering Company financed by the NER.[2] Excluding land purchases, it cost roughly £500,000 to construct, which has been estimated as being around £55 million in 2016 prices. On 29 July 1902, work on digging out the foundations for the structure commenced at the Newcastle end.[2][5]

The foundations under the three large river piers were laid by divers working in caissons (watertight chambers) underwater in compressed air.[2] This was dangerous work and no one under the age of 40 could be employed in this capacity and each man spent four hours per shift in the caissons. Only one man died and became seriously ill attributed to working in compressed.[4] Other workers became ill from breathing sulphuretted hydrogen from the coal seams that the foundations were dug into.[2]

Rock was excavated from inside the caissons by blasting; workers took refuge in an air-locked chamber in the access shaft while charges were detonated. The caissons were then filled with roughly 28,450 tonnes of concrete and the piers were constructed on top. The sandstone and granite piers were built in a triple-shaft arrangement, 6.6 by 9.3 m (22 by 31 ft) for the side-shafts and 4.1 by 9.3 m (13 by 31 ft) for the central shaft.[5]

Once the piers were finished, the spans were assembled timber trestles. The spans above the river were erected one at a time while half the river was closed to traffic.[5] The bridge deck consists of steel lattice girders of the double Warren truss type, 8.2 m (27 ft) deep overall at 3.35 m (11.0 ft) spacing. The deck is 15.2 m (50 ft) wide and the weight of the steel work is estimated to be around 5,820 tonnes.[5]

An elevated cableway across the river was used during construction.[4] It was the world's longest cableway, having a length of 463.5 m (1,521 ft) suspended 61 m (200 ft) above the Tyne at high water. A 7.6 cm (3.0 in) diameter steel cable conveyed more than 23,000 tonnes of material. When the bridge was finished, the cableway was dismantled and the cable was taken to Swan Hunter and Wigham Richardson shipyard in Wallsend, where it was used in the launch of the RMS Mauretania.[4]

Although not finished, on 10 July 1906, the bridge was opened by King Edward VII from a temporary platform at the Gateshead end.[2] It was named after the reigning monarch, King Edward VII. According to the Evening Chronicle, it was the first bridge to carry four main tracks. The distance between the tracks has been too narrow for some modern, high-speed trains.[2]

On 27 September 1906, the bridge's strength was demonstrated by running ten locomotives, each weighing around 100 tons, coupled together in two sets of five, over the bridge at a speed of 6–8 mph (10–13 km/h). The locomotives ran side-by-side to exert the maximum possible strain on each of the bridge's girders.[2]

Operating life

On 1 October 1906, the bridge was opened to general traffic[2][5] and trains using the East Coast Main Line could access Newcastle Station via the new crossing, while trains for Sunderland and Middlesbrough continued to use the High Level Bridge. In March 1907, a freight line to Dunston was opened to the east of the main line.[5]

During 1908, Harrison commented that "... there was nothing very striking in the design of the bridge except that it was rather larger in span and width and greater in height above the river than most bridges that had been erected in the last few years". He thought that its caissons were the largest that had been sunk since those used for the Forth Bridge.[5]

In 1959, the locomotive shed at Greenesfield, Gateshead was closed allowing the track layout across the bridge to be simplified, most notably the reduction from four lines to three.[5]

Between 1976 and 1991, British Rail electrified most of the East Coast Main Line and the bridge was equipped with overhead wiring gantries.[5]

In 1994, the bridge was Grade II listed.[2]

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to King Edward VII bridge. |

- Historic England. "KING EDWARD RAILWAY BRIDGE (1242100)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- Morton, David (7 July 2016). "The Tyne's King Edward VII railway bridge at 110: A brief history in 14 historic facts". Evening Chronicle. Newcastle upon Tyne: Trinity Mirror. Retrieved 1 September 2018.

- "King Edward VII Bridge". SINE. Newcastle University. Archived from the original on 19 May 2005. Retrieved 11 March 2017.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- "King Edward VII Bridge". Tyne & Wear Archives & Museums. Archived from the original on 29 April 2012. Retrieved 11 March 2017.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- "King Edward VII Rail Bridge." engineering-timelines.com, Retrieved: 21 May 2018.

External links

| Next bridge upstream | River Tyne | Next bridge downstream |

| Redheugh Bridge A189 |

King Edward VII Bridge Grid reference: NZ246632 |

Queen Elizabeth II Metro Bridge |

| Next railway bridge upstream | River Tyne | Next railway bridge downstream |

| Scotswood Railway Bridge Disused (now carries water and gas mains) |

King Edward VII Bridge Grid reference: NZ246632 |

Queen Elizabeth II Metro Bridge |