Winterton-on-Sea

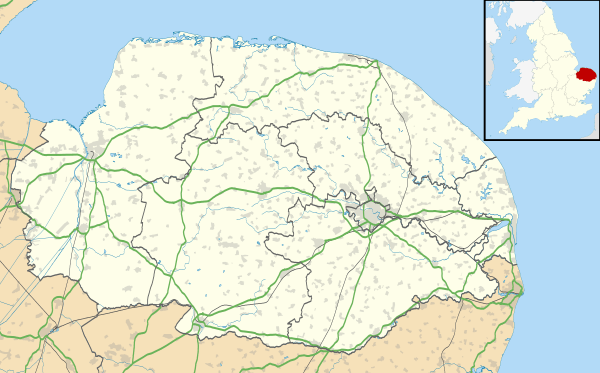

Winterton-on-Sea is a village and civil parish on the coast of Norfolk, England. It is 8 mi (13 km) north of Great Yarmouth and 19 mi (31 km) east of Norwich.[2]

| Winterton-on-Sea | |

|---|---|

The Church of the Holy Trinity & All Saints | |

Winterton-on-Sea Location within Norfolk | |

| Area | 5.70 km2 (2.20 sq mi) |

| Population | 1,278 (2011)[1] |

| • Density | 224/km2 (580/sq mi) |

| OS grid reference | TG488193 |

| Civil parish |

|

| District |

|

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | GREAT YARMOUTH |

| Postcode district | NR29 |

| Dialling code | 01493 |

| Police | Norfolk |

| Fire | Norfolk |

| Ambulance | East of England |

| UK Parliament | |

Introduction

The civil parish has an area of 2.2 sq mi (5.7 km2) and in the 2001 census had a population of 1,359 in 589 households. Winterton-on-Sea borders the villages of Hemsby, Horsey and Somerton. For the purposes of local government, the parish falls within the district of Great Yarmouth.[3]

Between the village and the North Sea are the Winterton Dunes which include a 109 hectare National Nature Reserve and are inhabited by several notable species such as the natterjack toad.

Winterton-on-Sea has received awards on several occasions in the Anglia in Bloom competition.[4]

Winterton as a resort

It has been described as "a very pleasant place to spend a holiday" [5] and "one of the great natural beauty-spots of Norfolk".[6] The coast near the village has a sandy beach. The village has a fish and chip shop, a pub and a post office.

History

There has been a church since Anglo-Saxon times; the parish was created in 967.[7] Some historians believe it was the seasonal "tun", meaning settlement, of farmers from East Somerton who were fishermen during the winter. By Norman times it had become a separate village.[8]

Winterton-on-Sea is recorded in the Domesday Book as Wintretona or Wintretuna.[9]

A glossy black erratic boulder "the size of a large pig" is located in The Lane close to the junction with Back Street. The stone was moved in 1931, this led to riots as the move was deemed responsible for poor fishing. In the following year it was moved to its present location.[10]

The church, Holy Trinity and All Saints, mostly dates back to the 16th century and is 132 feet (40 m) tall.[11] The lean-to chapel north of the chancel is from the 13th century and could have been an anchorite's cell but is more likely to have been an early example of a vestry or sacristry. The porch dates from about 1459.[7]

The hazardous nature of the coastline at Winterton-on-Sea is marked by its lighthouse whose history extends from James I to the First World War.[12]

The Fisherman's Return, a brick and flint public house, dates from the end of the 17th century.[5]

In the late 18th century marram grass was planted to stabilise the coastline against sea encroachments, and by the early 19th century there was a barrier of dunes between high water mark and the ridge on which the lighthouse stood, leaving a valley (The Valley) between.[13]

Edward Fawcett was a Winterton fisherman who joined the Royal Navy. He sailed with Captain James Clark Ross on HMS Erebus' exploration of the Antarctic as boatswain's mate. He was not on Erebus when it made its fatal Arctic voyage under Sir John Franklin, but took part in one of the attempted rescues in HMS Investigator as part of the McClure Arctic Expedition and was in the first group of people to travel through the North West Passage. The crew of Investigator were trapped for three years in the pack ice before making contact via sledging expeditions with HMS Resolute and abandoning their ship. Resolute was in turn also trapped in the ice and abandoned, and the survivors marched across the ice to Beechey Island from where other ships returned them home. Fawcett spent his retirement in Winterton.[14][15][16] Timbers from Resolute were eventually made into the Resolute desk used in the White House Oval Office by American presidents.

Between 1851 and 1861 a number of Winterton families migrated south to Caister-on-Sea. Many of those families joined the Caister Beachmen and founded arguably the basis of the modern Lifeboat service. The most notable of these men was James Haylett.

During World War II, anti-invasion defences were constructed around Winterton-on-Sea. They included a number of pillboxes. The beaches were protected with unusually extensive barriers of scaffolding and large numbers of anti-tank cubes.[17]

Art and literature

Daniel Defoe mentions the village in Robinson Crusoe and A tour thro' the whole island of Great Britain, published in 1719 and from 1724 respectively.

In 1864 the novelist Wilkie Collins visited the village while preparing Armadale, and met nineteen-year-old Martha Rudd who became his unmarried partner. They had three children together.[18][19] He was an admirer of Daniel Defoe and in particular of Robinson Crusoe, which is referred to many times in his subsequent novel The Moonstone, and wanted to explore the area where the character was initially shipwrecked.[19]

The author and communist Sylvia Townsend Warner, one of the Bright Young Things of the 1920s, frequently stayed with Valentine Ackland at Hill House and they both wrote poetry inspired by the Winterton beach and dunes.[18]

From the mid 1950s to the early 1970s Leslie Davenport, a member of the Norwich Twenty Group of painters, led up to 200 artists, writers and musicians living on the beach and dunes for six weeks every summer.[6]

In 1956, at 78 years old, the fisherman Sam Larner was discovered as a folk singer. His performances were often broadcast, he performed at music venues in London, and a record was published. There is a blue plaque on his cottage.[20]

The 1977 film Julia includes scenes filmed in the village. [21]

References

- "Parish population 2011". Retrieved 24 August 2015.

- Ordnance Survey (2002). OS Explorer Map 252 - Norfolk Coast East. ISBN 0-319-21888-0.

- "Census population and household counts for unparished urban areas and all parishes". Office for National Statistics & Norfolk County Council (2001). p. 1. Archived from the original on 11 February 2017. Retrieved 2 December 2005.

- "Winterton in Bloom". winterton-on-sea.net. 2015. Retrieved 22 August 2015.

- David, Joy (1990). The Hidden Places Of Norfolk and Suffolk. Plymouth: M&M Publishing. ISBN 1-871815-10-X.

- Nobbs, George (1973). Pubs To Visit In East Anglia. Norwich: Wensum Books. ISBN 0 903619 03 2.

- "Homeusers archive". homeusers. 2001. Archived from the original on 13 July 2001. Retrieved 10 July 2016.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- "Winterton Norfolk Genealogy". familysearch.org. 2016. Retrieved 10 July 2016.

- "Domesday Book". domesdaybook.co.uk. 1086. Retrieved 7 July 2016.

- "The Stone, Winterton-on-Sea". Norfolk Heritage Explorer. Retrieved 27 July 2016.

- "Lots going on at the Church". winterton-on-sea.net. 2015. Retrieved 22 August 2015.

- "Winterton on Sea". norfolkcoast.co.uk. 2013. Retrieved 22 August 2015.

- Long, Neville (1983). Lights of East Anglia. Lavenham: T. Dalton. ISBN 9780861380282.

- Stein, Glenn M. (2015). Discovering The North-West Passage. The Four-Year Arctic Odyssey of H.M.S. Investigator and the McClure Expedition. North Carolina: McFarland and Company. ISBN 978-0-7864-7708-1.

- McClure, Robert (1856). The Discovery Of a Northwest Passage. Canada: Touch Wood Editions. ISBN 978-1-77151-009-7.

- "National Library Of New Zealand". The Press newspaper. 1895. Retrieved 17 July 2016.

- Foot, William (2006). Beaches, fields, streets, and hills ... the anti-invasion landscapes of England, 1940. Council for British Archaeology. ISBN 1-902771-53-2.

- "Literary Norfolk". literarynorfolk.co.uk. 2016. Retrieved 12 July 2016.

- Clarke, William (1991). The Secret Life Of Wilkie Collins. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee. ISBN 978-1-56663-582-0.

- "SamFest". samfest.co.uk. 2015. Retrieved 17 July 2016.

- "Norfolk (and some Suffolk) film and TV location". Literary Norfolk. Retrieved 28 April 2020.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Winterton-on-Sea. |

- Information from Genuki Norfolk on Winterton-on-Sea.

- Winterton-on-Sea village website

- https://wintertononsea.co.uk/village/in-bloom.html

- http://wintertononsea.co.uk/village/church.html

- http://www.norfolkcoast.co.uk/location_norfolk/vp_wintertononsea.htm

- http://www.wintertononsea.co.uk/ WintertonOnSea.co.uk - About the village, accommodation & village news

- https://wintertononsea.co.uk/whats-on.html

- Literary connections of Winterton