Wezmeh

The Wezmeh Cave is an archaeological site near Islamabad Gharb, western Iran, around 470 km (290 mi) southwest of the capital Tehran. The site was discovered in 1999 and excavated in 2001 by a team of Iranian archaeologists under the leadership of Dr. Kamyar Abdi.[1] Wezmeh cave was re-excavated by a team under direction of Fereidoun Biglari in 2019.

Wezmeh Cave غار وزمه | |

|---|---|

Wezmeh Cave | |

| Coordinates: 34°03′31″N 46°38′52″E | |

| Province | Kermanshah |

| County | Eslamabad-e Gharb |

| Bakhsh | Central |

Late Pleistocene animals

Large numbers of animal fossil remains have been discovered so far. The earliest and the latest dates obtained on animal bones are 70,000 years BP and 11,000 years BP, respectively. The animal remains belong to red fox, spotted hyena, brown bear, wolf, lion, leopard, wild cat, equids, rhinoceros, wild boar, deer, aurochs, wild goat and sheep etc. The faunal remains were studied by Marjan Mashkour and her colleagues at the Natural History Museum in Paris and osteological department of National Museum of Iran.

Human remains

Pleistocene

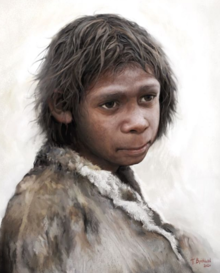

Several fragmented human bones and teeth were discovered in the site. Among these human remains one tooth studied in detail by Paleoanthropologists such as Erik Trinkaus. Wezmeh 1, also known as Wezmeh Child, represented by an isolated unerupted human maxillary right premolar tooth (P3 or possibly P4) of an individual between 6-10 years old. It is relatively large compared with both Holocene and Late Pleistocene P3 and P4. Later Researchers analyzed it by non-destructive gamma spectrometry that resulted in a date of around 25,000 years BP (Upper Paleolithic). But later analysis showed that the gamma spectrometry dates the date was the minimum age and the tooth is substantially older. Endostructural features and quantified crown tissue proportions and semilandmark-based geometric morphometric analyses of the enamel-dentine junction aligns it closely with Neanderthals and shows that it is distinct from the fossil and extant modern human pattern. Therefore it is the first direct evidence of the Neanderthal presence in the Iranian Zagros.[2] Given that the cave was a carnivore den during the late Pleistocene, it is probable that the Wezmeh Child was killed, or had its remains scavenged, by carnivores who used the cave as a den.

Holocene

A human metatarsal bone fragment has also been analyzed and dated to the Neolithic period, about 9000 years ago. The DNA from this bone fragment shows that it is from a distinct genetic group, which was not known to scientists before. He belongs to the Y-DNA haplogroup G2b[3], specifically its branch G-Y37100[4], and mitochondrial haplogroup J1d6. He had brown eyes, relatively dark skin, and black hair, although Neolithic Iranians carried reduced pigmentation-associated alleles in several genes and derived alleles at 7 of the 12 loci, showing the strongest signatures of selection in ancient Eurasians. Isotopic analysis showed the man's diet included cereals, a sign that he had learned how to cultivate crops. This cave site was sporadically used by later Chalcolithic groups of the region, who used it as pen for their herds. This cave was listed as an archaeological and paleonthological site on the National Register of Historic Sites (17843) in 2006.

References

- Farnaz Broushaki (2016). "Early Neolithic genomes from the eastern Fertile Crescent". Science. 353 (6298): 499–503. Bibcode:2016Sci...353..499B. doi:10.1126/science.aaf7943. PMC 5113750. PMID 27417496.

|access-date=requires|url=(help) - Zanolli, Clément, Fereidoun Biglari, Marjan Mashkour, Kamyar Abdi, Herve Monchot, Karyne Debue, Arnaud Mazurier, Priscilla Bayle, Mona Le Luyer, Hélène Rougier, Erik Trinkaus, Roberto Macchiarelli. (2019). Neanderthal from the Central Western Zagros, Iran. Structural reassessment of the Wezmeh 1 maxillary premolar. Journal of Human Evolution, Vol: 135.

- https://science.sciencemag.org/content/sci/suppl/2016/07/13/science.aaf7943.DC1/Broushaki.SM.pdf

- https://www.yfull.com/tree/G-Y37100/

- Abdi, K., F. Biglari, S. Heydari,2002. Islamabad Project 2001. Test Excavations at Wezmeh Cave. Archäologische Mitteilungen aus Iran und Turan.34, 171-194.

- Broushaki, Farnaz; Thomas, Mark G.; Link, Vivian; López, Saioa; Van Dorp, Lucy; Kirsanow, Karola; Hofmanová, Zuzana; Diekmann, Yoan; Cassidy, Lara M.; Díez-Del-Molino, David; Kousathanas, Athanasios; Sell, Christian; Robson, Harry K.; Martiniano, Rui; Blöcher, Jens; Scheu, Amelie; Kreutzer, Susanne; Bollongino, Ruth; Bobo, Dean; Davoudi, Hossein; Munoz, Olivia; Currat, Mathias; Abdi, Kamyar; Biglari, Fereidoun; Craig, Oliver E.; Bradley, Daniel G.; Shennan, Stephen; Veeramah, Krishna R.; Mashkour, Marjan; et al. (2016). "Early Neolithic genomes from the eastern Fertile Crescent". Science. 353 (6298): 499–503. Bibcode:2016Sci...353..499B. doi:10.1126/science.aaf7943. PMC 5113750. PMID 27417496.

- Djamali, Morteza; Biglari, Fereidoun; Abdi, Kamyar; Andrieu-Ponel, Valérie; De Beaulieu, Jacques-Louis; Mashkour, Marjan; Ponel, Philippe (2011). "Pollen analysis of coprolites from a late Pleistocene–Holocene cave deposit (Wezmeh Cave, west Iran): Insights into the late Pleistocene and late Holocene vegetation and flora of the central Zagros Mountains". Journal of Archaeological Science. 38 (12): 3394–3401. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2011.08.001.

- Monchot, Hervé (2008). "Des hyènes tachetées au Pléistocène supérieur dans le Zagros (grotte Wezmeh, Iran)". Mom Éditions. 49 (1): 65–78.

- Monchot, H., Mashkour, M., Biglari, F., & Abdi, K. (2019). The Upper Pleistocene brown bear (Carnivora, Ursidae) in the Zagros: Evidence from Wezmeh Cave, Kermanshah, Iran. In Annales de Paléontologie (p. 102381). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annpal.2019.102381

- Trinkaus, E.; Biglari, F.; Mashkour, M.; Monchot, H.; Reyss, J. L.; Rougier, H.; Heydari, S.; Abdi, K. (2008). "Late Pleistocene human remains from Wezmeh Cave, western Iran". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 135 (4): 371–8. doi:10.1002/ajpa.20753. PMID 18000894.

- Mashkour, M.; Monchot, H.; Trinkaus, E.; Reyss, J.-L.; Biglari, F.; Bailon, S.; Heydari, S.; Abdi, K. "Carnivores and their prey in the Wezmeh Cave (Kermanshah, Iran): a Late Pleistocene refuge in the Zagros". International Journal of Osteoarchaeology. 19 (6): 678–694. doi:10.1002/oa.997. eISSN 1099-1212. ISSN 1047-482X.

- Zanolli, Clément, Fereidoun Biglari, Marjan Mashkour, Kamyar Abdi, Herve Monchot, Karyne Debue, Arnaud Mazurier, Priscilla Bayle, Mona Le Luyer, Hélène Rougier, Erik Trinkaus, Roberto Macchiarelli. (2019). A Neanderthal from the Central Western Zagros, Iran. Structural reassessment of the Wezmeh 1 maxillary premolar. Journal of Human Evolution, Vol: 135.