Rat

| Rats | |

|---|---|

| |

| Brown rat (Rattus norvegicus) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| (unranked): | Glires |

| Order: | Rodentia |

Rats are various medium-sized, long-tailed rodents. Species of rats are found throughout the order Rodentia, but stereotypical rats are found in the genus Rattus. Other rat genera include Neotoma (pack rats), Bandicota (bandicoot rats) and Dipodomys (kangaroo rats).

Rats are typically distinguished from mice by their size. Generally, when someone discovers a large muroid rodent, its common name includes the term rat, while if it is smaller, its name includes the term mouse. The common terms rat and mouse are not taxonomically specific.

Species and description

The best-known rat species are the black rat (Rattus rattus) and the brown rat (Rattus norvegicus). This group, generally known as the Old World rats or true rats, originated in Asia. Rats are bigger than most Old World mice, which are their relatives, but seldom weigh over 500 grams (17 1⁄2 oz) in the wild.[1]

The term rat is also used in the names of other small mammals that are not true rats. Examples include the North American pack rats (aka wood rats[2]) and a number of species loosely called kangaroo rats.[2] Rats such as the bandicoot rat (Bandicota bengalensis) are murine rodents related to true rats but are not members of the genus Rattus.

Male rats are called bucks; unmated females, does, pregnant or parent females, dams; and infants, kittens or pups. A group of rats is referred to as a mischief.[3]

The common species are opportunistic survivors and often live with and near humans; therefore, they are known as commensals. They may cause substantial food losses, especially in developing countries.[4] However, the widely distributed and problematic commensal species of rats are a minority in this diverse genus. Many species of rats are island endemics, some of which have become endangered due to habitat loss or competition with the brown, black, or Polynesian rat.[5]

Wild rodents, including rats, can carry many different zoonotic pathogens, such as Leptospira, Toxoplasma gondii, and Campylobacter.[6] The Black Death is traditionally believed to have been caused by the microorganism Yersinia pestis, carried by the tropical rat flea (Xenopsylla cheopis), which preyed on black rats living in European cities during the epidemic outbreaks of the Middle Ages; these rats were used as transport hosts. Another zoonotic disease linked to the rat is foot-and-mouth disease.[7]

Rats become sexually mature at age 6 weeks, but reach social maturity at about 5 to 6 months of age. The average lifespan of rats varies by species, but many only live about a year due to predation.[8]

The black and brown rats diverged from other Old World rats in the forests of Asia during the beginning of the Pleistocene.[9]

Rat tails

The characteristic long tail of most rodents is a feature that has been extensively studied in various rat species models, which suggest three primary functions of this structure: thermoregulation,[10] minor proprioception, and a nocifensive-mediated degloving response.[11] Rodent tails—particularly in rat models—have been implicated with a thermoregulation function that follows from its anatomical construction. This particular tail morphology is evident across the family Muridae, in contrast to the bushier tails of Sciuridae, the squirrel family. The tail is hairless and thin skinned but highly vascularized, thus allowing for efficient countercurrent heat exchange with the environment. The high muscular and connective tissue densities of the tail, along with ample muscle attachment sites along its plentiful caudal vertebrae, facilitate specific proprioceptive senses to help orient the rodent in a three-dimensional environment. Lastly, murids have evolved a unique defense mechanism termed degloving that allows for escape from predation through the loss of the outermost integumentary layer on the tail. However, this mechanism is associated with multiple pathologies that have been the subject of investigation.

Multiple studies have explored the thermoregulatory capacity of rodent tails by subjecting test organisms to varying levels of physical activity and quantifying heat conduction via the animals' tails. One study demonstrated a significant disparity in heat dissipation from a rat's tail relative to its abdomen.[12] This observation was attributed to the higher proportion of vascularity in the tail, as well as its higher surface-area-to-volume ratio, which directly relates to heat's ability to dissipate via the skin. These findings were confirmed in a separate study analyzing the relationships of heat storage and mechanical efficiency in rodents that exercise in warm environments. In this study, the tail was a focal point in measuring heat accumulation and modulation.

On the other hand, the tail's ability to function as a proprioceptive sensor and modulator has also been investigated. As aforementioned, the tail demonstrates a high degree of muscularization and subsequent innervation that ostensibly collaborate in orienting the organism.[13] Specifically, this is accomplished by coordinated flexion and extension of tail muscles to produce slight shifts in the organism's center of mass, orientation, etc., which ultimately assists it with achieving a state of proprioceptive balance in its environment. Further mechanobiological investigations of the constituent tendons in the tail of the rat have identified multiple factors that influence how the organism navigates its environment with this structure. A particular example is that of a study in which the morphology of these tendons is explicated in detail.[14] Namely, cell viability tests of tendons of the rat's tail demonstrate a higher proportion of living fibroblasts that produce the collagen for these fibers. As in humans, these tendons contain a high density of golgi tendon organs that help the animal assess stretching of muscle in situ and adjust accordingly by relaying the information to higher cortical areas associated with balance, proprioception, and movement.

The characteristic tail of murids also displays a unique defense mechanism known as degloving in which the outer layer of the integument can be detached in order to facilitate the animal's escape from a predator. This evolutionary selective pressure has persisted despite a multitude of pathologies that can manifest upon shedding part of the tail and exposing more interior elements to the environment.[15] Paramount among these are bacterial and viral infection, as the high density of vascular tissue within the tail becomes exposed upon avulsion or similar injury to the structure. The degloving response is a nocifensive response, meaning that it occurs when the animal is subjected to acute pain, such as when a predator snatches the organism by the tail.

As pets

Specially bred rats have been kept as pets at least since the late 19th century. Pet rats are typically variants of the species brown rat - but black rats and giant pouched rats are also sometimes kept. Pet rats behave differently from their wild counterparts depending on how many generations they have been kept as pets.[16] Pet rats do not pose any more of a health risk than pets such as cats or dogs.[17] Tamed rats are generally friendly and can be taught to perform selected behaviors.

As subjects for scientific research

In 1895, Clark University in Worcester, Massachusetts, established a population of domestic albino brown rats to study the effects of diet and for other physiological studies. Over the years, rats have been used in many experimental studies, adding to our understanding of genetics, diseases, the effects of drugs, and other topics that have provided a great benefit for the health and wellbeing of humankind.

The aortic arches of the rat are among the most commonly studied in murine models due to marked anatomical homology to the human cardiovascular system.[18] Both rat and human aortic arches exhibit subsequent branching of the brachiocephalic trunk, left common carotid artery, and left subclavian artery, as well as geometrically similar, nonplanar curvature in the aortic branches.[18] Aortic arches studied in rats exhibit abnormalities similar to those of humans, including altered pulmonary arteries and double or absent aortic arches.[19] Despite existing anatomical analogy in the inthrathoracic position of the heart itself, the murine model of the heart and its structures remains a valuable tool for studies of human cardiovascular conditions.[20]

The rat's larynx has been used in experimentations that involve inhalation toxicity, allograft rejection, and irradiation responses. One experiment described four features of the rat's larynx. The first being the location and attachments of the thyroarytenoid muscle, the alar cricoarytenoid muscle, and the superior cricoarytenoid muscle, the other of the newly named muscle that ran from the arytenoid to a midline tubercle on the cricoid. The newly named muscles were not seen in the human larynx. In addition, the location and configuration of the laryngeal alar cartilage was described. The second feature was that the way the newly named muscles appear to be familiar to those in the human larynx. The third feature was that a clear understanding of how MEPs are distributed in each of the laryngeal muscles was helpful in understanding the effects of botulinum toxin injection. The MEPs in the posterior cricoarytenoid muscle, lateral cricoarytenoid muscle, cricothyroid muscle, and superior cricoarytenoid muscle were focused mostly at the midbelly. In addition, the medial thyroarytenoid muscle were focused at the midbelly while the lateral thyroarytenoid muscle MEPs were focused at the anterior third of the belly. The fourth and final feature that was cleared up was how the MEPs were distributed in the thyroarytenoid muscle. [21]

Laboratory rats have also proved valuable in psychological studies of learning and other mental processes (Barnett 2002), as well as to understand group behavior and overcrowding (with the work of John B. Calhoun on behavioral sink). A 2007 study found rats to possess metacognition, a mental ability previously only documented in humans and some primates.[22][23]

Domestic rats differ from wild rats in many ways. They are calmer and less likely to bite; they can tolerate greater crowding; they breed earlier and produce more offspring; and their brains, livers, kidneys, adrenal glands, and hearts are smaller (Barnett 2002).

Brown rats are often used as model organisms for scientific research. Since the publication of the rat genome sequence,[24] and other advances, such as the creation of a rat SNP chip, and the production of knockout rats, the laboratory rat has become a useful genetic tool, although not as popular as mice. When it comes to conducting tests related to intelligence, learning, and drug abuse, rats are a popular choice due to their high intelligence, ingenuity, aggressiveness, and adaptability. Their psychology seems in many ways similar to that of humans.

Entirely new breeds or "lines" of brown rats, such as the Wistar rat, have been bred for use in laboratories. Much of the genome of Rattus norvegicus has been sequenced.[25]

General intelligence

Early studies found evidence both for and against measurable intelligence using the "g factor" in rats.[26][27] Part of the difficulty of understanding animal cognition generally, is determining what to measure.[28] One aspect of intelligence is the ability to learn, which can be measured using a maze like the T-maze.[28] Experiments done in the 1920s showed that some rats performed better than others in maze tests, and if these rats were selectively bred, their offspring also performed better, suggesting that in rats an ability to learn was heritable in some way.[28]

As food

Rat meat is a food that, while taboo in some cultures, is a dietary staple in others.[29]

Working rats

Rats have been used as working animals. Tasks for working rats include the sniffing of gunpowder residue, demining, acting and animal-assisted therapy.

For odor detection

Rats have a keen sense of smell and are easy to train. These characteristics have been employed, for example, by the Belgian non-governmental organization APOPO, which trains rats (specifically African giant pouched rats) to detect landmines and diagnose tuberculosis through smell.[30]

In the spread of disease

Rats can serve as zoonotic vectors for certain pathogens and thus spread disease, such as bubonic plague, Lassa fever, leptospirosis, and Hantavirus infection.[31]

They are also associated with human dermatitis because they are frequently infested with blood feeding rodent mites such as the tropical rat mite (Ornithonyssus bacoti) and spiny rat mite (Laelaps echidnina), which will opportunistically bite and feed on humans,[32] where the condition is known as rat mite dermatitis.[33]

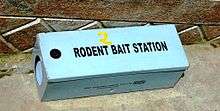

As pests

Rats have long been considered deadly pests. Once considered a modern myth, the rat flood in India occurs every fifty years, as armies of bamboo rats descend upon rural areas and devour everything in their path.[34] Rats have long been held up as the chief villain in the spread of the Bubonic Plague;[35] however, recent studies show that rats alone could not account for the rapid spread of the disease through Europe in the Middle Ages.[36] Still, the Centers for Disease Control does list nearly a dozen diseases[37] directly linked to rats.

Most urban areas battle rat infestations. A 2015 study by the American Housing Survey (AHS) found that eighteen percent of homes in Philadelphia showed evidence of rodents. Boston, New York City, and Washington, D.C., also demonstrated significant rodent infestations.[38] Indeed, rats in New York City are famous for their size and prevalence. The urban legend that the rat population in Manhattan equals that of its human population was definitively refuted by Robert Sullivan in his book Rats but illustrates New Yorkers' awareness of the presence, and on occasion boldness and cleverness, of the rodents.[39] New York has specific regulations for eradicating rats; multifamily residences and commercial businesses must use a specially trained and licensed rat catcher.[40]

Rats have the ability to swim up sewer pipes into toilets.[41][42] Rats will infest any area that provides shelter and easy access to sources of food and water, including under sinks, near garbage, and inside walls or cabinets. [43]

As invasive species

When introduced into locations where rats previously did not exist, they can wreak an enormous degree of environmental degradation. Rattus rattus, the black rat, is considered to be one of the world's worst invasive species.[44] Also known as the ship rat, it has been carried worldwide as a stowaway on seagoing vessels for millennia and has usually accompanied men to any new area visited or settled by human beings by sea. The similar species Rattus norvegicus, the brown rat or wharf rat, has also been carried worldwide by ships in recent centuries.

The ship or wharf rat has contributed to the extinction of many species of wildlife, including birds, small mammals, reptiles, invertebrates, and plants, especially on islands. True rats are omnivorous, capable of eating a wide range of plant and animal foods, and have a very high birth rate. When introduced to a new area, they quickly reproduce to take advantage of the new food supply. In particular, they prey on the eggs and young of forest birds, which on isolated islands often have no other predators and thus have no fear of predators.[45] Some experts believe that rats are to blame for between forty percent and sixty percent of all seabird and reptile extinctions, with ninety percent of those occurring on islands. Thus man has indirectly caused the extinction of many species by accidentally introducing rats to new areas.[46]

Rat-free areas

Rats are found in nearly all areas of Earth which are inhabited by human beings. The only rat-free continent is Antarctica, which is too cold for rat survival outdoors, and its lack of human habitation does not provide buildings to shelter them from the weather. However, rats have been introduced to many of the islands near Antarctica, and because of their destructive effect on native flora and fauna, efforts to eradicate them are ongoing. In particular, Bird Island (just off rat-infested South Georgia Island), where breeding seabirds could be badly affected if rats were introduced, is subject to special measures and regularly monitored for rat invasions.[47]

As part of island restoration, some islands' rat populations have been eradicated to protect or restore the ecology. Hawadax Island, Alaska was declared rat free after 229 years and Campbell Island, New Zealand after almost 200 years. Breaksea Island in New Zealand was declared rat free in 1988 after an eradication campaign based on a successful trial on the smaller Hawea Island nearby.

In January 2015, an international "Rat Team" set sail from the Falkland Islands for the British Overseas Territory of South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands on board a ship carrying three helicopters and 100 tons of rat poison with the objective of "reclaiming the island for its seabirds". Rats have wiped out more than 90% of the seabirds on South Georgia, and the sponsors hope that once the rats are gone, it will regain its former status as home to the greatest concentration of seabirds in the world. The South Georgia Heritage Trust, which organized the mission describes it as "five times larger than any other rodent eradication attempted worldwide".[48] That would be true if it were not for the rat control program in Alberta (see below).

The Canadian province of Alberta is notable for being the largest inhabited area on Earth which is free of true rats due to very aggressive government rat control policies. It has large numbers of native pack rats, also called bushy-tailed wood rats, but they are forest-dwelling vegetarians which are much less destructive than true rats.[49]

Alberta was settled relatively late in North American history and only became a province in 1905. Black rats cannot survive in its climate at all, and brown rats must live near people and in their structures to survive the winters. There are numerous predators in Canada's vast natural areas which will eat non-native rats, so it took until 1950 for invading rats to make their way over land from Eastern Canada.[50] Immediately upon their arrival at the eastern border with Saskatchewan, the Alberta government implemented an extremely aggressive rat control program to stop them from advancing further. A systematic detection and eradication system was used throughout a control zone about 600 kilometres (400 mi) long and 30 kilometres (20 mi) wide along the eastern border to eliminate rat infestations before the rats could spread further into the province. Shotguns, bulldozers, high explosives, poison gas, and incendiaries were used to destroy rats. Numerous farm buildings were destroyed in the process. Initially, tons of arsenic trioxide were spread around thousands of farm yards to poison rats, but soon after the program commenced the rodenticide and medical drug warfarin was introduced, which is much safer for people and more effective at killing rats than arsenic.[51]

Forceful government control measures, strong public support and enthusiastic citizen participation continue to keep rat infestations to a minimum.[52] The effectiveness has been aided by a similar but newer program in Saskatchewan which prevents rats from even reaching the Alberta border. Alberta still employs an armed rat patrol to control rats along Alberta's borders. About ten single rats are found and killed per year, and occasionally a large localized infestation has to be dug out with heavy machinery, but the number of permanent rat infestations is zero.[53]

In culture

Ancient Romans did not generally differentiate between rats and mice, instead referring to the former as mus maximus (big mouse) and the latter as mus minimus (little mouse).[54]

On the Isle of Man, there is a taboo against the word "rat".[55]

Asian cultures

The rat (sometimes referred to as a mouse) is the first of the twelve animals of the Chinese zodiac. People born in this year are expected to possess qualities associated with rats, including creativity, intelligence, honesty, generosity, ambition, a quick temper and wastefulness. People born in a year of the rat are said to get along well with "monkeys" and "dragons", and to get along poorly with "horses".

In Indian tradition, rats are seen as the vehicle of Ganesha, and a rat's statue is always found in a temple of Ganesh. In the northwestern Indian city of Deshnoke, the rats at the Karni Mata Temple are held to be destined for reincarnation as Sadhus (Hindu holy men). The attending priests feed milk and grain to the rats, of which the pilgrims also partake.

European cultures

European associations with the rat are generally negative. For instance, "Rats!" is used as a substitute for various vulgar interjections in the English language. These associations do not draw, per se, from any biological or behavioral trait of the rat, but possibly from the association of rats (and fleas) with the 14th-century medieval plague called the Black Death. Rats are seen as vicious, unclean, parasitic animals that steal food and spread disease. However, some people in European cultures keep rats as pets and conversely find them to be tame, clean, intelligent, and playful.

Rats are often used in scientific experiments; animal rights activists allege the treatment of rats in this context is cruel. The term "lab rat" is used, typically in a self-effacing manner, to describe a person whose job function requires them to spend a majority of their work time engaged in bench-level research (such as postgraduate students in the sciences).

Terminology

Rats are frequently blamed for damaging food supplies and other goods, or spreading disease. Their reputation has carried into common parlance: in the English language, "rat" is often an insult or is generally used to signify an unscrupulous character; it is also used, as a synonym for the term nark, to mean an individual who works as a police informant or who has turned state's evidence. Writer/director Preston Sturges created the humorous alias "Ratskywatsky" for a soldier who seduced, impregnated, and abandoned the heroine of his 1944 film, The Miracle of Morgan's Creek. It is a term (noun and verb) in criminal slang for an informant – "to rat on someone" is to betray them by informing the authorities of a crime or misdeed they committed. Describing a person as "rat-like" usually implies he or she is unattractive and suspicious.

Among trade unions, the word "rat" is also a term for nonunion employers or breakers of union contracts, and this is why unions use inflatable rats.[56]

Fiction

Depictions of rats in fiction are historically inaccurate and negative. The most common falsehood is the squeaking almost always heard in otherwise realistic portrayals (i.e. nonanthropomorphic). While the recordings may be of actual squeaking rats, the noise is uncommon – they may do so only if distressed, hurt, or annoyed. Normal vocalizations are very high-pitched, well outside the range of human hearing. Rats are also often cast in vicious and aggressive roles when in fact, their shyness helps keep them undiscovered for so long in an infested home.

The actual portrayals of rats vary from negative to positive with a majority in the negative and ambiguous.[57] The rat plays a villain in several mouse societies; from Brian Jacques's Redwall and Robin Jarvis's The Deptford Mice, to the roles of Disney's Professor Ratigan and Kate DiCamillo's Roscuro and Botticelli. They have often been used as a mechanism in horror; being the titular evil in stories like The Rats or H.P. Lovecraft's The Rats in the Walls[57] and in films like Willard and Ben. Another terrifying use of rats is as a method of torture, for instance in Room 101 in George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four or The Pit and the Pendulum by Edgar Allan Poe.

Selfish helpfulness —those willing to help for a price— has also been attributed to fictional rats.[57] Templeton, from E. B. White's Charlotte's Web, repeatedly reminds the other characters that he is only involved because it means more food for him, and the cellar-rat of John Masefield's The Midnight Folk requires bribery to be of any assistance.

By contrast, the rats appearing in the Doctor Dolittle books tend to be highly positive and likeable characters, many of whom tell their remarkable life stories in the Mouse and Rat Club established by the animal-loving doctor.

Some fictional works use rats as the main characters. Notable examples include the society created by O'Brien's Mrs. Frisby and the Rats of NIMH, and others include Doctor Rat, and Rizzo the Rat from The Muppets. Pixar's 2007 animated film Ratatouille is about a rat described by Roger Ebert as "earnest... lovable, determined, [and] gifted" who lives with a Parisian garbage-boy-turned-chef.[58]

Mon oncle d'Amérique ("My American Uncle"), a 1980 French film, illustrates Henri Laborit's theories on evolutionary psychology and human behaviors by using short sequences in the storyline showing lab rat experiments.

In Harry Turtledove's science fiction novel Homeward Bound, humans unintentionally introduce rats to the ecology at the home world of an alien race which previously invaded Earth and introduced some of its own fauna into its environment. A. Bertram Chandler pitted the space-bound protagonist of a long series of novels, Commodore Grimes, against giant, intelligent rats who took over several stellar systems and enslaved their human inhabitants. "The Stainless Steel Rat" is nickname of the (human) protagonist of a series of humorous science fiction novels written by Harry Harrison.

Wererats, therianthropic creatures able to take the shape of a rat,[59] have appeared in the fantasy or horror genre since the 1970s. The term is a neologism coined in analogy to werewolf. The concept has since become common in role playing games like Dungeons & Dragons[59][60][61] and fantasy fiction like the Anita Blake series.[62].

The Pied Piper

One of the oldest and most historic stories about rats is "The Pied Piper of Hamelin", in which a rat-catcher leads away an infestation with enchanted music. The piper is later refused payment, so he in turn leads away the town's children. This tale, traced to Germany around the late 13th century, has inspired adaptations in film, theatre, literature, and even opera. The subject of much research, some theories have intertwined the tale with events related to the Black Plague, in which black rats played an important role. Fictional works based on the tale that focus heavily on the rat aspect include Pratchett's The Amazing Maurice and his Educated Rodents, and Belgian graphic novel Le Bal du Rat Mort (The Ball of the Dead Rat).

See also

References

- "Habits, Habitat & Types of Mice". Live Science. Archived from the original on 24 May 2015. Retrieved 23 May 2015.

- Britannica Concise Encyclopedia. Chicago, IL: Britannica Digital Learning. 2017 – via Credo Reference.

- "Creature Feature Rats". ABC.net.au. Archived from the original on 24 May 2015. Retrieved 23 May 2015.

- Meerburg BG, Singleton GR, Leirs H (2009). "The Year of the Rat ends: time to fight hunger!". Pest Manag Sci. 65 (4): 351–2. doi:10.1002/ps.1718. PMID 19206089. Archived from the original on 2012-12-17.

- Stokes, Vicki L.; Banks, Peter B.; Pech, Roger P.; Spratt, David M. (2009). "Competition in an invaded rodent community reveals black rats as a threat to native bush rats in littoral rainforest of south-eastern Australia" (PDF). Journal of Applied Ecology. 46 (6): 1239–1247. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2664.2009.01735.x. Retrieved 23 May 2015.

- Meerburg BG, Singleton GR, Kijlstra A (2009). "Rodent-borne diseases and their risks for public health". Crit Rev Microbiol. 35 (3): 221–70. doi:10.1080/10408410902989837. PMID 19548807.

- Capel-Edwards, Maureen (October 1970). "Foot-and-mouth disease in the brown rat". Journal of Comparative Pathology. 80 (4): 543–548. doi:10.1016/0021-9975(70)90051-4. PMID 4321688.

- "How old is a rat in human years?". RatBehavior.org. Archived from the original on 12 June 2015. Retrieved 23 May 2015.

- Aplin, Ken P.; Suzuki, Hitoshi; Chinen, Alejandro A.; Chesser, R. Terry; ten Have, José; Donnellan, Stephen C.; et al. (November 2011). "Multiple Geographic Origins of Commensalism and Complex Dispersal History of Black Rats". PLOS One. 6 (11): e26357. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...626357A. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0026357. PMC 3206810. PMID 22073158.

- "Rat Tails". Rat Behavior and Biology. Retrieved 30 July 2020.

- Grant, Karen. "Degloving Injury". Rat Health Guide. Retrieved 30 July 2020.

- Wanner, Samuel (2015). "Thermoregulatory responses in exercising rats: methodological aspects and relevance to human physiology". Temperature. 2 (4): 457–75. doi:10.1080/23328940.2015.1119615. PMC 4844073. PMID 27227066.

- Mackenzie, SJ (2015). "Innervation and function of rat tail muscles for modeling cauda equina injury and repair". Muscle and Nerve. 52 (1): 94–102. doi:10.1002/mus.24498. PMID 25346299.

- Bruneau, Amelia (2010). "Preparation of Rat Tail Tendons for Biomechanical and Mechanobiological Studies". Journal of Visualized Experiments. 41 (41): 2176. doi:10.3791/2176. PMC 3156064. PMID 20729800.

- Milcheski, Dimas (2012). "Development of an experimental model of degloving injury in rats". Brazilian Journal of Plastic Surgery. 27: 514–17.

- "Wild Rats in Captivity and Domestic Rats in the Wild". Ratbehaviour.org. Archived from the original on 2009-04-13. Retrieved 2009-07-04.

- "Merk Veterinary Manual Global Zoonoses Table". Merckvetmanual.com. Archived from the original on 2007-02-17. Retrieved 2006-11-24.

- Casteleyn, Christophe; Trachet, Bram; Van Loo, Denis; Devos, Daniel G H; Van den Broeck, Wim; Simoens, Paul; Cornillie, Pieter (2017-04-19). "Validation of the murine aortic arch as a model to study human vascular diseases". Journal of Anatomy. 216 (5): 563–571. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7580.2010.01220.x. ISSN 0021-8782. PMC 2871992. PMID 20345858.

- Wilson, James G.; Warkany, Josef (1950-04-01). "Cardiac and Aortic Arch Anomalies in the Offspring of Vitamin a Deficient Rats Correlated with Similar Human Anomalies". Pediatrics. 5 (4): 708–725. ISSN 0031-4005. PMID 15417271. Archived from the original on 2017-08-18.

- Casteleyn, Christophe; Trachet, Bram; Van Loo, Denis; Devos, Daniel G H; Van den Broeck, Wim; Simoens, Paul; Cornillie, Pieter (2017-04-27). "Validation of the murine aortic arch as a model to study human vascular diseases". Journal of Anatomy. 216 (5): 563–571. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7580.2010.01220.x. ISSN 0021-8782. PMC 2871992. PMID 20345858.

- Inagi, Katsuhide; Schultz, Edward; Ford, Charles (1998). "An Anatomic Study of the Rat Larynx: Establishing the Rat Model for Neuromuscular Function". Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. 118 (1): 74–81. doi:10.1016/s0194-5998(98)70378-x. PMID 9450832.

- Foote, Allison L.; Jonathon D. Crystal (20 March 2007). "Metacognition in the rat". Current Biology. 17 (6): 551–555. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2007.01.061. PMC 1861845. PMID 17346969. Archived from the original on 3 July 2012.

- "Rats Capable Of Reflecting On Mental Processes". Sciencedaily.com. 2007-03-09. Archived from the original on 2012-10-10. Retrieved 2012-09-24.

- Gibbs RA et al.: Genome sequence of the Brown Norway rat yields insights into mammalian evolution.: Nature. 2004 April 1; 428(6982):475–6.

- "Genome project". www.ensembl.org. Archived from the original on 26 April 2006. Retrieved 17 February 2007.

- Lashley, K., Brain Mechanisms and Intelligence, Dover Publications, New York, 1929/1963, 186 pp.

- Thorndike, R (1935). "Organization of behavior in the albino rat". Genet. Psychol. Monogr. 17: 1–70.

- Matzel, LD; Sauce, B (October 2017). "Individual differences: Case studies of rodent and primate intelligence". Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Learning and Cognition. 43 (4): 325–340. doi:10.1037/xan0000152. PMC 5646700. PMID 28981308.

- Newvision Archive (2005-03-10). "Rats for dinner, a delicacy to some, a taboo to many". Newvision.co.ug. Archived from the original on 2012-09-22. Retrieved 2012-09-24.

- "Video of Bart Weetjens talk on use of rats as odour detectors". Ted.com. Archived from the original on 2012-10-07. Retrieved 2012-09-24.

- "Information on other rodent-related diseases – Leptospirosis Information". Leptospirosis Information. Archived from the original on 2016-10-31. Retrieved 2016-10-31.

- Watson, J. (2008). New building, old parasite: Mesostigmatid mites—an ever-present threat to barrier rodent facilities. ILAR journal, 49(3), 303-309.

- Engel, Peter M.; Welzel, J.; Maass, M.; Schramm, U.; Wolff, H. H. (1998). "Tropical Rat Mite Dermatitis: Case Report and Review". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 27 (6): 1465–1469. doi:10.1086/515016. ISSN 1058-4838. PMID 9868661.

- "Massive plagues of rats swarm across India every fifty years". Io9.com. Archived from the original on 2013-05-21. Retrieved 2013-03-15.

- "The Black Plague". University of North Carolina. Archived from the original on 2013-03-01. Retrieved 2013-03-15.

- Maev Kennedy (2011-08-17). "Black Death study lets rats off the hook". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 2013-08-27. Retrieved 2013-03-15.

- "CDC – Diseases directly transmitted by rodents – Rodents". Centers for Disease Control. 2011-06-07. Archived from the original on 2013-03-17. Retrieved 2013-03-15.

- Clark, Patrick (2017-01-17). "The Most Vermin-Infested American Cities". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 2017-01-18. Retrieved 2017-01-18.

- Wilsey, Sean (2005-03-17). "Sean Wilsey reviews 'Rats' by Robert Sullivan · LRB 17 March 2005". London Review of Books. Lrb.co.uk. pp. 9–10. Archived from the original on 9 February 2013. Retrieved 2013-03-15.

- "Questions and Answers Regarding New York State Pest Management Program". DOEC of NY State. Archived from the original on 2014-12-17. Retrieved 2014-11-24.

- Klein, Stephanie (2014-10-17). "How to keep the rats from coming up through your toilet". Archived from the original on 2015-09-01. Retrieved 2015-08-23.

- "See How Easily a Rat Can Wriggle Up Your Toilet". video.nationalgeographic.com. Archived from the original on 2015-08-21. Retrieved 2015-08-23.

- "Identify and Prevent Rodent Infestations". epa.gov. United States Environmental Protection Agency. 2013-10-31. Retrieved 2019-12-05.

- "100 of the World's Worst Invasive Alien Species". Global Invasive Species Database. Archived from the original on 27 February 2013. Retrieved 17 February 2013.

- "Rattus rattus (mammal)". Global Invasive Species Database. Archived from the original on 20 October 2015. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

- "Humans outdone by Rats for causing Extinctions". Science Avenger. 2007-12-05. Archived from the original on 19 January 2015. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

- "Preventing the introduction of non-native species to Antarctica". British Antarctic Survey. Archived from the original on 8 January 2015. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

- Gill, First= Victoria (23 January 2015). "South Georgia rat eradication mission sets sail". BBC. Archived from the original on 24 January 2015. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- "Bushy-Tailed Woodrat (Pack Rat)". Pest Control Canada. Archived from the original on 29 June 2017. Retrieved 8 August 2017.

- "Rattus norvegicus (mammal) – Details of this species in Alberta". Global Invasive Species Database. Archived from the original on 26 October 2014. Retrieved 18 October 2014.

- "The History of Rat Control In Alberta". Alberta Department of Agriculture and Rural Development. Archived from the original on 25 September 2014. Retrieved 18 October 2014.

- "Rat Control in Alberta". Alberta Department of Agriculture and Rural Development. Archived from the original on 26 September 2014. Retrieved 18 October 2014.

- Giovannetti, Justin (26 November 2015). "On the frontlines of Alberta's war against rats". Toronto Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on 22 January 2017. Retrieved 8 August 2017.

- "NATURE NOTES: Mus Maximus". www.wigantoday.net. Archived from the original on 2019-02-02. Retrieved 2019-02-01.

- Eyers, Jonathan (2011). Don't Shoot the Albatross!: Nautical Myths and Superstitions. A&C Black, London, UK. ISBN 978-1-4081-3131-2.

- "Nevada Journal: Louts and the Rat World". Nj.npri.org. Archived from the original on 2013-05-20. Retrieved 2012-09-24.

- Clute, John; John Grant (March 15, 1999). The Encyclopedia of Fantasy. St. Martin's Griffin. p. 642. ISBN 978-0-312-19869-5.

- Ebert, Roger (2008). Roger Ebert's Four-Star Reviews 1967–2007. Andrews McMeel Publishing. p. 637. ISBN 978-0-7407-7179-8.

Remy, the earnest little rat who is its hero, is such a lovable, determined, gifted rodent that I want to know what happens to him next, now that he has conquered the summit of French cuisine.

- David "Zeb" Cook; Steve Winter; Jon Pickens; et al. (1989). Monstrous Compendium Volume One. TSR, Inc. ISBN 0-8803-8738-6.

- Gygax, Gary and Robert Kuntz. Supplement I: Greyhawk (TSR, 1975).

Gygax, Gary. Monster Manual (TSR, 1977).

Allston, Aaron, Steven E. Schend, Jon Pickens, and Dori Watry. Dungeons & Dragons Rules Cyclopedia (TSR, 1991).

Dupuis, Ann. Night Howlers (TSR, 1992).

Swan, Rick (April 1993). "Role-playing Reviews". Dragon. Lake Geneva, Wisconsin: TSR (#192): 86.

Stewart, Doug, ed. Monstrous Manual (TSR, 1993).

Johnson, Kristin (September 1998). "Ecology of the Wererat". Dragon. TSR (251).

Williams, Skip, Jonathan Tweet, and Monte Cook. Monster Manual. Wizards of the Coast, 2000.

Poisso, Dean. "Animal Ancestry." Dragon #313 (Paizo Publishing, 2003). - Bryan Armor; Christine Gregory; Ellen Kiley; et al. (2000). Dragons of the East. White Wolf Publishing, Inc. p. 92. ISBN 1-56504-428-2.

- Fusco, Virginia (2015). Monstrous Figurations: Notes for a Feminist Reading (Tesis doctoral). Universidad Carlos III de Madrid. pp. 4, 122.

Further reading

- List of books and articles about rats, is a non-fiction list.

External links

| Look up rat in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Rats |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rats. |

- High-Resolution Images of the Rat Brain

- National Bio Resource Project for the Rat in Japan

- Rat Behaviour and Biology

- Rat Genome Database

- "Rat". New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

- "Rat". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- "Rat". Encyclopedia Americana. 1920.