Animal-assisted therapy

Animal-assisted therapy (AAT) is an alternative or complementary type of therapy that involves animals as a form of treatment.[1] It falls under the realm of Animal Assisted Interventions (AAI). AAI is general term that encompasses any intervention or treatment that includes an animal in a therapeutic context such as Emotional-Support Animals, Service/Assistance Animals (i.e., trained animals that assist and support with daily activities), and Animal Assisted Activity (AAA).[2][3][4] AAT contains sub-sections based on the type of animal, the targeted population, and how the animal is being incorporated into the therapeutic plan.[5] The most commonly used types of AAT are canine-assisted therapy and equine-assisted therapy. The goal of AAT is to improve a patient's social, emotional, or cognitive functioning and literature reviews state that animals can be useful for educational and motivational effectiveness for participants.[6][7] There are various studies documenting the positive effects of AAT reported through subjective self-rating scales and objective physiological measures, such as blood pressure, hormone levels, etc.

Physiological effects

Wilson's (1984) biophilia hypothesis is based on the premise that our attachment to and interest in animals stems from the strong possibility that human survival was partly dependent on signals from animals in the environment indicating safety or threat.[8] The biophilia hypothesis suggests that if we see animals at rest or in a peaceful state, this may signal to us safety, security and feelings of well-being which in turn may trigger a state where personal change and healing are possible.

Six neurotransmitters that influence mood have been documented to release after a 15-minute or more interaction with animals.[9] Mirror neuron activity and disease-perception through olfactory (smelling) ability in dogs may also play important roles in helping dogs connect with humans during therapeutic encounters.[6]

Medical uses

Animals can be used in a variety of settings such as prisons, nursing homes, mental institutions,[10][11] and in the home.[12][13] There are numerous techniques used in AAT, depending on the needs and condition of the patient. Assistance dogs are capable of assisting certain life activities and of helping people navigate outside of the home.[12][14]

As with all other interventions, assessing whether a program is effective as far as its outcomes are concerned is easier when the goals are clear and are able to be specified. There are a range of goals for animal assisted therapy programs relevant to children and young people, including enhanced capacity to form positive relationships with others. It is understood that pets provide benefits to those with mental health conditions, but further research is required to test the nature and extent of this relationship with an animal as a pet and how it differs between pets, emotional support animals, service animals, and animal-assisted therapy.[15]

Cognitive Rehabilitation Treatment

Acquired Brain Injury (ABI) survivors with cognitive impairments can benefit from AAT as part of a comprehensive and holistic rehabilitation treatment plan.[16]

Pediatric care

Therapists rely on techniques such as monitoring a child's behavior with the animal, their tone of voice, and indirect interviewing. AAT can be used in children with mental health problems, can be used as a stand-alone treatment or it can be used along with conventional methods.[17] Animals can be used as a distraction method when it comes to various situations or pain, and animals can also help bring happiness, pleasure, and entertainment to the pediatric population. Animals can also help improve children's moods and reinforce positive behaviors while helping to decrease negative ones.[18] AAT research most commonly reported results were decreased anxiety and pain within the pediatric population.[18][19] Dogs have shown to increase comfort and decrease pain in pediatric palliative care.[20] Specific tactics have not been researched, but collective reviews of varied techniques displayed similar results of increased comfort reports by children and guardians.[20]

Prisons

Animal-assistance programs may be useful in prisons to relieve stress of the inmates and workers, or to provide other benefits, but further study is needed to confirm the effectiveness of such programs in these settings.[21] Internal file data reviews, anecdotal stories, and surveys of inmate and staff perceptions have been used to gauge the effectiveness of animal-assisted therapy in prisons, but these methods are limited and have resulted in an inadequate assessment.[22][23]

Researchers have, however, begun to find methods of gauging the effectiveness of prison animal programs (PAP) by using Propensity Score Watching. Conclusions through this method showed that PAPs positively impact reductions in severe or violent infractions. A reduction in offenses statistically may reduce recidivism rates and increase former inmate job marketability and societal reintegration.[24]

Inmates training and being responsible for an animal can foster empathy, emotional intelligence, communication, and self-control. PAP's also benefit the animals involved as many come from situations where they faced abuse, neglect or euthanasia.[25]

Nursing homes

The findings offer proof of the concept that canine-assisted therapies are feasible and can elicit positive quality-of-life experiences in institutionalized people with dementia.[26] Researchers and practitioners need to elucidate the theoretical foundations of AATs. The Lived Environment Life Quality (LELQ) Model may serve as a guide for client-centered, occupation-focused, and ecologically valid approaches to animal-assisted occupational therapy beyond people with dementia.[26]

When elderly people are transferred to nursing homes or LTC facilities, they often become passive, agitated, withdrawn, depressed, and inactive because of the lack of regular visitors or the loss of loved ones.[27] Supporters of AAT say that animals can be helpful in motivating the patients to be active mentally and physically, keeping their minds sharp and bodies healthy.[7] A significant difference has been seen among verbal interactions among nursing home residents with a dog present.[28] Therapists or visitors who bring animals into their sessions at the nursing home are often viewed as less threatening, which increases the relationship between the therapist/visitor and patient.[29]

Types

Various animal species are used in animal-assisted therapy (AAT). Individual animals are evaluated with strict criteria before being used in AAT. The criteria include appropriate size, age, aptitude, typical behaviors and the correct level of training. The most common forms of AAT are with dogs and horses. There is also published research on dolphin therapy.[30]

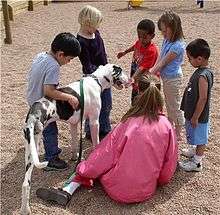

Canine-assisted therapy

In canine-assisted therapy, therapy dogs interact with clients in animal assisted interventions, to enhance therapeutic activities and well-being including the physical, cognitive, behavioral and socio-emotional functioning of clients.[31][32][33] Well trained therapy dogs exhibit the behavior that human clients construe as friendly and welcoming.[33] They comfort clients via body contact.[32] Therapy dogs are also required to possess a calm temperament for accommodating the contact with unfamiliar clients while they serve as a source of comfort.[32] They promote patients engaging in interactions which can help patient improve motor skills and establish trusting relationship with others. The interaction between patients and therapy dogs also aids reducing stressful and anxious feelings patients have.[32] Due to those benefits, canine assisted therapy is used as a complement to other therapies to treat diagnosis such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), autism spectrum disorder (ASD), and dementia.[31][33][32]

Canine assistance can also be used in classroom for promoting the development of creative writing and living skills and the participation of children in group activities.[31] There are programs called canine-assisted reading programs which facilitate children with special educational needs. These programs utilize the calm, non-judgmental, happy characteristics of canines to let the process of reading become more meaningful and enjoyable for children. With these benefits, researchers suggest to incorporating dogs into assisting learning and educational programs.[31]

Equine-related therapy

A distinction exists between hippotherapy and therapeutic horseback riding. The American Hippotherapy Association defines hippotherapy as a physical, occupational, and speech-language therapy treatment strategy that utilizes equine movement as part of an integrated intervention program to achieve functional outcomes, while the Professional Association of Therapeutic Horsemanship International (PATHI) defines therapeutic riding as a riding lesson specially adapted for people with special needs.[34] According to Marty Becker, hippotherapy programs are active "in twenty-four countries and the horse's functions have expanded to therapeutic riding for people with physical, psychological, cognitive, social, and behavioral problems".[34]:124 Hippotherapy has also been approved by the American Speech and Hearing Association as a treatment method for individuals with speech disorders.[34] In addition, equine assisted psychotherapy (EAP) uses horses for work with persons who have mental health issues. EAP often does not involve riding.[35][36] Additional information pertaining to equine assisted therapy can be seen with Laira Gold's open clinical study of EAT.[37]

Dolphin therapy

Dolphin assisted therapy refers to the controversial alternative medicine practice of swimming with dolphins. This form of therapy has been strongly criticized as having no long term benefit,[38] and being based on flawed observations.[39] Psychologists have cautioned that dolphin assisted therapy is not effective for any known condition and presents considerable risks to both human patients and the captive dolphins.[40] The child has a one-on-one session with a therapist in a marine park of some kind.[41] An ethical issue with data on dolphin-assisted therapy and the effectiveness of it is that most of the research is done by people who operate the dolphin-assisted therapy programs.[41]

Conditions Benefit from Animal-Assisted Therapy

Based on current research, there are many conditions/disorders that can benefit from animal-assisted therapy (AAT) in diverse settings around the world. Those conditions include psychological disorder, developmental disorder, dementia, cancer, chronic pain, advanced heart failure, etc.[32][30] Animal-assisted therapy is commonly used for psychological disorder. Disorders such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), autism spectrum disorder (ASD), post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), major depressive disorder (MDD) are part of psychological disorders that can benefit from animal-assisted therapy. [17][33][32][30]

Effectiveness

In recent decades, an increased number of research indicates the social, psychological, and physiological benefits of animal assisted therapy in health and education field.[31] Although the effectiveness of AAT is still unclear due to the lack of clarity regarding the degree to which the canine itself contributes in the recovery process,[32] there is a growing awareness that AAT may be effective in treating attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, autism spectrum disorder, and dementia.[42]

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder

Children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) may decrease behavioral issues and improve socialization skills with the intervention of AAT. Compared to children only received cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), children who received both canine-assisted therapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) had reduce in severity of ADHD symptoms.[17][33][32][30] However, the canine-assisted therapy had no effect on relieving ADHD symptoms in long-term treatment.[33]

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

Animal Assisted Therapy for the Treatment of Trauma in Military Veterans

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a psychological disorder affects people's mental health and has varying severity and forms.[43][44] PTSD is often difficult to treat due to high drop-out rates and low responses to traditional psychotherapeutic approaches and interventions.[3]

Animals have two types of effects, direct and indirect, on a mental health spectrum including biological, psychological, and social responses,[44] further targeting marked symptoms of PTSD (i.e., re-experiencing, avoidance, changes in beliefs/feelings, and hyperarousal). Direct effects of animals include a decrease in anxiety and blood pressure while indirect effects result in increased social interactions and overall participation in everyday activities.[44]

Biologically, specific neurochemicals are released when observing human and animal interactions.[44] Similarly, dog assistance can potentially mediate oxytocin which effects social and physical wellbeing and decrease blood pressure.[17] The psychological benefits of animals focus mainly on dog and human interactions, the reduction of anxiety and depressive symptoms, and increased resilience.[44] Animals in this capacity can further provide emotional and psychological assistance and support, addressing several PTSD symptoms.[44][2] The presence of an animal can alleviate intrusion symptoms by providing a reminder that there is no danger present.[2] Animals can further elicit positive emotions, targeting emotional numbing experiences.[2] Animal interactions also provide social benefits, providing companionship and alleviate feelings of loneliness and isolation through everyday routines and increased social interactions in public.[44][2]

The incorporation and involvement of animals dates back to the earliest forms of organized combat.[44] Dogs, in particular, were utilized in different capacities.[44] Ancient armies employed dogs as Soldiers and companions which extended to modern combat including dogs as a crucial asset in communication, detection, and intimidation.[44] In World War II, dogs were used in therapy as emotional support during the war.[3] While a range of animals can be utilized in AAIs, dogs and horses have been investigated and explored as forms of rehabilitation for veterans suffering from PTSD.[44] Dog assisted therapy and therapeutic horseback riding are non-invasive methods for treating post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in veterans.[17].

Canines can easily integrate into a multitude of environments, are highly responsive to humans, and are very intelligent.[45] For those reasons, dogs are the most common animal used in AAIs.[4] Dogs are typically categorized according to the level of training received and the specific needs of the individual.[4] A service dog provides relief through specialized support related to a physical, mental, or psychological disability.[46] Emotional support animals (ESAs) solely provide psychological relief and do not require specialized training.[46] Therapy animals often provide additional support in a therapeutic environment by supporting counselors or therapists in their therapeutic duties.[46] While service dogs, ESAs, and therapy dogs can support the diverse symptoms that veterans, specifically bred and selected dogs, PTSD Service Dogs (PSDs), are trained and assigned to veterans with PTSD to support with daily life activities [47] as well as with emotional and mental health needs.[44]

Dogs provide subjective positive effects to veterans and serve as a compassionate reminder to veterans suffering from PTSD that danger is not present, creating a safe space for the veteran.[3] They are often sensitive to humans and have the ability to adapt their behavior accordingly by doing tasks such as preventing panic, waking a veteran from a nightmare, and nudging to help the veteran “stay in the present”.[48] Dogs also provide veterans with a nonjudgmental and safe environment that can help a veteran express feelings and process thoughts without interruption, criticism or advice.[49] Interactions, such as petting, playing and walking, with the dog can increase physical activity, reduce anxiety, and provide encouragement to stay in the present moment.[49] The interaction between dog and veterans supports social interactions for isolated veterans, reduces symptoms associated with PTSD such as depression and anxiety, and increases veterans’ calmness.[17]

Similar to dogs, horses have been included in the treatment of veterans suffering from PTSD [4] by providing an accepting and nonjudgmental environment,[50] which further facilitates a veterans’ ability to cope with symptoms associated with PTSD.[50] Because horses are social animals, they are capable of creating and responding to relationships based on the veteran's energy, providing an opportunity for veterans to regain the ability to form trusting relationships.[51] Therapeutic work with horses varies from ground-based activities, mounted activities, or a combination of both.[4] In the therapeutic context, horses can promote cognitive reframing as well as an increase in the use of mindfulness practice.[50] While there is limited research and standardized instruments to measure the effects, veterans who have participated in pilot programs have better communicate skills, self-awareness, and self-esteem,[50] promoting safety and support during the transition into civilian life.[52] Long term effects of equine based interventions with veterans include increased happiness, social support, and better sleep hygiene [4] because they are able to process information regarding their emotions and behaviors in a nonjudgmental space.[52]

While AAIs can be effective, they also have limitations due to limited research and findings on AAIs and veterans with PTSD.[3]Furthermore, studies approved yield small sample sizes which limit the power to detect changes [50] as well as the specific tasks that are particularly helpful to veterans.[48] AAT may also obstruct veterans from cultivating their own way of control over stressful situation.

Autism Spectrum Disorder

AAT could reduce the symptoms of ASD such as aggressiveness, irritability, distractibility, and hyperactivity.[17] In one review,[17] five out of nine studies reviewed showed positive effects of therapeutic horseback riding on children with ASD. Canine assisted intervention provides a calmer environment by reducing the stress, irritation, and anxiety that children with ASD experience.[30][53] Playing with dogs increases the positive mood in children with ASD.[53] Animals also can serve as a social catalyst. In the presence of animals, children with ASD are more likely engage in social interactions with humans.[53] However, the impact of AAT upon parent-child interaction is not clear.[17]

Dementia

AAT encourages expressions of emotions and cognitive stimulation through discussions and reminiscing of memories while the patient bonds with the animal. Studies have found that animal assisted therapies (particularly using dogs) resulted in measurable quality of life improvements for patients with dementia.[54] Patients with dementia were also found to improve their social interactions and their scores on the Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory (CMAI).[55] AAT has also been shown to slightly reduce depressive symptoms in people with dementia in a 2019 systematic review.[56]

Limitations

There is limited scientific research on the use of AAT within the population of adults who have been sexually assaulted. While animals do tend to comfort victims, animal therapy may not be the catalyst that provides positive success in therapy sessions. As mentioned above, adults tend not to focus as much on having an animal companion, and therefore, animal therapy cannot be attributed as the reason for success in those types of therapy sessions.[5] There are some ethical concerns that arise when applying animal therapy to younger victims of sexual assault. For example, if a child is introduced to an animal that is not their pet, the application of animal therapy can cause some concerns. First of all, some children may not be comfortable with animals or may be frightened which could be avoided by asking permission to use animals in therapy. Second, a special bond is created between animal and child during animal therapy. Therefore, if the animal in question does not belong to the child, there may be some negative side effects when the child discontinues therapy. The child will have become attached to the animal, which does raise some ethical issues as far as subjecting a child to the disappointment and possible relapse that can occur after therapy discontinues.[5]

The effectiveness of AAT is also still unclear due to the lack of clarity regarding the degree to which the canine itself contributes in the recovery process.[32]

There are some concerns specific to dolphin-assisted therapy: First, it is potentially hazardous to the human patients, and it is harmful to the dolphins themselves; by taking dolphins out of their natural environment and putting them in captivity for therapy can be hazardous to their well-being.[40] Second, dolphin-assisted therapy has been strongly criticized as having no long term benefit,[38] and being based on flawed observations.[39] Third, psychologists have cautioned that dolphin assisted therapy is not effective for any known condition.[40]

History

Research has found animals can have an overall positive effect on health and improve mood and quality of life.[57][3][58] The positive effect has been linked to the human-animal bond. In a variety of settings, such as prisons, nursing homes, and mental institutions, animals are used to assist people with different disabilities or disorders.[12] In modern times animals are seen as "agents of socialization" and as providers of "social support and relaxation".[59] The earliest reported use of AAT for the mentally ill took place in the late 18th century at the York Retreat in England, led by William Tuke.[60] Patients at this facility were allowed to wander the grounds which contained a population of small domestic animals. These were believed to be effective tools for socialization. In 1860, the Bethlem Hospital in England followed the same trend and added animals to the ward, greatly influencing the morale of the patients living there.[60] However, in other pieces of literature it states that AAT was used as early as 1792 at the Quaker Society of Friends York Retreat in England.[61] Velde, Cipriani & Fisher also state "Florence Nightingale appreciated the benefits of pets in the treatment of individuals with illness."

The US military promoted the use of dogs as a therapeutic intervention with psychiatric patients in 1919 at St Elizabeth's Hospital in Washington, DC.

Sigmund Freud kept many dogs and often had his chow Jofi present during his pioneering sessions of psychoanalysis. He noticed that the presence of the dog was helpful because the patient would find that their speech would not shock or disturb the dog and this reassured them and so encouraged them to relax and confide. This was most effective when the patient was a child or adolescent.[62]

Modern AAT may have been influenced by attachment theory.[63]

Increased recognition of the value of human–pet bonding was noted by Dr. Boris Levinson in 1961.[61] Dr. Boris Levinson accidentally used animals in therapy with children when he left his dog alone with a difficult child, and upon returning, found the child talking to the dog.[64]

See also

- Animal cognition

- Animal consciousness

- Care farming

- Emotional support animal

- Human-canine bond

- Service animal

- Service dog

- Therapy cat

- Therapy dog

References

- Kruger KA, Serpell JA (2010). "Animal-assisted interventions in mental health". Handbook on Animal-Assisted Therapy. pp. 33–48. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-381453-1.10003-0. ISBN 9780123814531.

- O'Haire ME, Guérin NA, Kirkham AC (2015). "Animal-Assisted Intervention for trauma: a systematic literature review". Frontiers in Psychology. 6: 1121. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01121. PMC 4528099. PMID 26300817.

- Glintborg C, Hansen TG (April 2017). "How Are Service Dogs for Adults with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder Integrated with Rehabilitation in Denmark? A Case Study". Animals. 7 (5): 33. doi:10.3390/ani7050033. PMC 5447915. PMID 28441333.

- O'Haire ME, Guérin NA, Kirkham AC, Daigle CL (2015). "Animal-Assisted Intervention for Trauma, Including Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder" (PDF). HABRI Central Briefs.

- Charry-Sánchez JD, Pradilla I, Talero-Gutiérrez C (August 2018). "Animal-assisted therapy in adults: A systematic review". Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice. 32: 169–180. doi:10.1016/j.ctcp.2018.06.011. PMID 30057046.

- Marcus DA (April 2013). "The science behind animal-assisted therapy". Current Pain and Headache Reports. 17 (4): 322. doi:10.1007/s11916-013-0322-2. PMID 23430707.

- "Animal Assisted Therapy". American Humane Association.

- Wilson EO (1984). Biophilia. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-07441-6. OCLC 10754298.

- Odendaal JS (October 2000). "Animal-assisted therapy - magic or medicine?". Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 49 (4): 275–80. doi:10.1016/S0022-3999(00)00183-5. PMID 11119784.

- Barker SB, Dawson KS (June 1998). "The effects of animal-assisted therapy on anxiety ratings of hospitalized psychiatric patients". Psychiatric Services. 49 (6): 797–801. doi:10.1176/ps.49.6.797. PMID 9634160. S2CID 21924861.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Netting FE, Wilson CC, New JC (1987). "The Human-Animal Bond: Implications for Practice". Social Work. 32 (1): 60–64. doi:10.1093/sw/32.1.60. ISSN 0037-8046. JSTOR 23713617.

- Beck A (1983). Between Pets and People: the Importance of Animal Companionship. New York: Putnam. ISBN 978-0-399-12775-5.

- Walsh F (December 2009). "Human-animal bonds II: the role of pets in family systems and family therapy". Family Process. 48 (4): 481–99. doi:10.1111/j.1545-5300.2009.01297.x. PMID 19930434.

- Yamamoto M, Hart LA (2019-06-11). "Professionally- and Self-Trained Service Dogs: Benefits and Challenges for Partners With Disabilities". Frontiers in Veterinary Science. 6: 179. doi:10.3389/fvets.2019.00179. PMC 6579932. PMID 31245394.

- Brooks HL, Rushton K, Lovell K, Bee P, Walker L, Grant L, Rogers A (February 2018). "The power of support from companion animals for people living with mental health problems: a systematic review and narrative synthesis of the evidence". BMC Psychiatry. 18 (1): 31. doi:10.1186/s12888-018-1613-2. PMC 5800290. PMID 29402247.

- Stapleton M (June 2016). "Effectiveness of Animal Assisted Therapy after brain injury: A bridge to improved outcomes in CRT". NeuroRehabilitation. 39 (1): 135–40. doi:10.3233/NRE-161345. PMID 27341368.

- Hoagwood KE, Acri M, Morrissey M, Peth-Pierce R (2016-01-25). "Animal-Assisted Therapies for Youth with or at risk for Mental Health Problems: A Systematic Review". Applied Developmental Science. 21 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1080/10888691.2015.1134267. PMC 5546745. PMID 28798541.

- Goddard AT, Gilmer MJ (2015). "The Role and Impact of Animals with Pediatric Patients". Pediatric Nursing. 41 (2): 65–71. PMID 26292453. Archived from the original on 2017-12-05. Retrieved 2017-12-04.

- Braun C, Stangler T, Narveson J, Pettingell S (May 2009). "Animal-assisted therapy as a pain relief intervention for children". Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice. 15 (2): 105–9. doi:10.1016/j.ctcp.2009.02.008. PMID 19341990.

- Gilmer MJ, Baudino MN, Tielsch Goddard A, Vickers DC, Akard TF (September 2016). "Animal-Assisted Therapy in Pediatric Palliative Care". The Nursing Clinics of North America. 51 (3): 381–95. doi:10.1016/j.cnur.2016.05.007. PMID 27497015.

- Allison M, Ramaswamy M (September 2016). "Adapting Animal-Assisted Therapy Trials to Prison-Based Animal Programs". Public Health Nursing. 33 (5): 472–80. doi:10.1111/phn.12276. PMID 27302852.

- Furst G (2006). "Prison-based animal programs: A national survey". The Prison Journal. 86: 407–430. doi:10.1177/0032885506293242 – via ResearchGate.

- Bachi K (2013). "Equine-facilitated prison-based programs within the context of prison-based animal programs: State of the science review". Journal of Offender Rehabilitation. 52: 46–74. doi:10.1080/10509674.2012.734371 – via ResearchGate.

- Van Wormer J, Kigerl A, Hamilton Z (September 2017). "Digging deeper: Exploring the value of prison-based dog handler programs". The Prison Journal. 97 (4): 520–38. doi:10.1177/0032885517712481.

- "Prison animal programs are benefitting both inmates and hard-to-adopt dogs: Experts". ABC News. Retrieved 2019-10-05.

- Wood W, Fields B, Rose M, McLure M (September–October 2017). "Animal-Assisted Therapies and Dementia: A Systematic Mapping Review Using the Lived Environment Life Quality (LELQ) Model". The American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 71 (5): 7105190030p1–7105190030p10. doi:10.5014/ajot.2017.027219. PMID 28809656.

- .Sutton, D., M. (1984). Use of pets in therapy with elderly nursing home residents. Toronto, Canada: American Psychological Association

- Fick KM (1993-06-01). "The Influence of an Animal on Social Interactions of Nursing Home Residents in a Group Setting". American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 47 (6): 529–534. doi:10.5014/ajot.47.6.529. ISSN 0272-9490. PMID 8506934.

- Marx MS, Cohen-Mansfield J, Regier NG, Dakheel-Ali M, Srihari A, Thein K (February 2010). "The impact of different dog-related stimuli on engagement of persons with dementia". American Journal of Alzheimer's Disease and Other Dementias. 25 (1): 37–45. doi:10.1177/1533317508326976. PMC 3142779. PMID 19075298.

- Andreasen G (2017). "Animal-assisted therapy and occupational therapy". Journal of Occupational Therapy, Schools, & Early Intervention. 10: 1–17. doi:10.1080/19411243.2017.1287519.

- Fung S (2017). "Canine-assisted reading programs for children with special educational needs: rationale and recommendations for the use of dogs in assisting learning". Educational Review. 69 (4): 435–450. doi:10.1080/00131911.2016.1228611.

- Krause-Parello CA, Sarni S, Padden E (December 2016). "Military veterans and canine assistance for post-traumatic stress disorder: A narrative review of the literature". Nurse Education Today. 47: 43–50. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2016.04.020. PMID 27179660.

- Lundqvist M, Carlsson P, Sjödahl R, Theodorsson E, Levin LÅ (July 2017). "Patient benefit of dog-assisted interventions in health care: a systematic review". BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 17 (1): 358. doi:10.1186/s12906-017-1844-7. PMC 5504801. PMID 28693538.

- Becker M (2002). The Healing Power of Pets: Harnessing the Amazing Ability of Pets to Make and Keep People Happy and Healthy. New York: Hyperion. ISBN 978-0-7868-6808-7.

- "What is EAP and EAL?". Equine Assisted Growth and Learning Association. Archived from the original on 2012-03-25. Retrieved 2012-03-18.

- Quiroz Rothe E, Jiménez Vega B, Mazo Torres R, Campos Soler SM, Molina RM (2005). "From kids and horses: Equine facilitated psychotherapy for children" (PDF). International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology. 5 (2): 373–383.

- Bivens A, Leinart D, Klontz B, Klontz T (2007). "The Effectiveness of Equine-Assisted Experiential Therapy: Results of an Open Clinical Trial". Society & Animals. 15 (3): 257–267. doi:10.1163/156853007x217195.

- Nathanson DE (1998). "Long-Term Effectiveness of Dolphin-Assisted Therapy for Children with Severe Disabilities". Anthrozoös: A Multidisciplinary Journal of the Interactions of People and Animals. 11 (1): 22–32. doi:10.2752/089279398787000896.

- Marino L, Lilienfeld SO (2007). "Dolphin-Assisted Therapy: More Flawed Data and More Flawed Conclusions". Anthrozoös: A Multidisciplinary Journal of the Interactions of People and Animals. 20 (3): 239–249. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.554.7777. doi:10.2752/089279307X224782.

- "Dolphin 'Therapy' A Dangerous Fad, Researchers Warn". Science Daily. 2007-12-18. Retrieved 2012-03-18.

- Humphries T (May 2003). "Effectiveness of dolphin-assisted therapy as a behavioral intervention for young children with disabilities". Bridges. 1 (6).

- Kamioka H, Okada S, Tsutani K, Park H, Okuizumi H, Handa S, et al. (April 2014). "Effectiveness of animal-assisted therapy: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials". Complementary Therapies in Medicine. 22 (2): 371–90. doi:10.1016/j.ctim.2013.12.016. PMID 24731910.

- Krause-Parello CA, Sarni S, Padden E (December 2016). "Military veterans and canine assistance for post-traumatic stress disorder: A narrative review of the literature". Nurse Education Today. 47: 43–50. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2016.04.020. PMID 27179660.

- Gillett J, Weldrick R (2014). Effectiveness of psychiatric service dogs in the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder among veterans. Hamilton, ON: McMaster University.

- Cole M, Howard M (2013). History, principles and practice: A practical guide to the diagnosis and treatment of disease using living organisms. Springer Science + Business Media.

- Schoenfeld-Tacher R, Hellyer P, Cheung L, Kogan L (June 2017). "Public Perceptions of Service Dogs, Emotional Support Dogs, and Therapy Dogs". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 14 (6): 642. doi:10.3390/ijerph14060642. PMC 5486328. PMID 28617350.

- van Houtert EA, Endenburg N, Wijnker JJ, Rodenburg B, Vermetten E (2018-09-11). "Erratum: The study of service dogs for veterans with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: a scoping literature review". European Journal of Psychotraumatology. 9 (Suppl 3): 1518199. doi:10.1080/20008198.2018.1518199. PMC 6136358. PMID 30221635.

- Yarborough BJ, Owen-Smith AA, Stumbo SP, Yarborough MT, Perrin NA, Green CA (July 2017). "An Observational Study of Service Dogs for Veterans With Posttraumatic Stress Disorder". Psychiatric Services. 68 (7): 730–734. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.201500383. PMID 28292227.

- Stern SL, Donahue DA, Allison S, Hatch JP, Lancaster CL, Benson TA, Johnson AL, Jeffreys MD, Pride D (2013-01-01). "Potential Benefits of Canine Companionship for Military Veterans with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)". Society & Animals. 21 (6): 568–581. doi:10.1163/15685306-12341286. ISSN 1568-5306.

- Johnson RA, Albright DL, Marzolf JR, Bibbo JL, Yaglom HD, Crowder SM, Carlisle GK, Willard A, Russell CL, Grindler K, Osterlind S, Wassman M, Harms N (January 2018). "Effects of therapeutic horseback riding on post-traumatic stress disorder in military veterans". Military Medical Research. 5 (1): 3. doi:10.1186/s40779-018-0149-6. PMC 5774121. PMID 29502529.

- Voelpel P, Escallier L, Fullerton J, Abitbol L (May 2018). "Interaction Between Veterans and Horses: Perceptions of Benefits". Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services. 56 (5): 7–10. doi:10.3928/02793695-20180305-05.

- Lanning BA, Krenek N (2013). "Guest Editorial: Examining effects of equine-assisted activities to help combat veterans improve quality of life". Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development. 50 (8): vii–xiii. doi:10.1682/jrrd.2013.07.0159. PMID 24458903.

- Fine A (2015). Handbook on Animal-Assisted Therapy : Foundations and Guidelines for Animal-Assisted Interventions. Elsevier Science & Technology. pp. 226–229. ISBN 9780128014363.

- Wood W, Fields B, Rose M, McLure M (2017). "Animal-Assisted Therapies and Dementia: A Systematic Mapping Review Using the Lived Environment Life Quality (LELQ) Model". The American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 71 (5): 7105190030p1–7105190030p10. doi:10.5014/ajot.2017.027219. PMID 28809656.

- Cherniack EP, Cherniack AR (2014). "The benefit of pets and animal-assisted therapy to the health of older individuals". Current Gerontology and Geriatrics Research. 2014: 623203. doi:10.1155/2014/623203. PMC 4248608. PMID 25477957.

- Lai NM, Chang SM, Ng SS, Tan SL, Chaiyakunapruk N, Stanaway F (November 2019). "Animal-assisted therapy for dementia". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019 (11). doi:10.1002/14651858.CD013243.pub2. PMC 6953240. PMID 31763689.

- New JC, Wilson CC, Netting FE (1987-01-01). "The Human-Animal Bond: Implications for Practice". Social Work. 32 (1): 60–64. doi:10.1093/sw/32.1.60. ISSN 0037-8046.

- Fine AH (2010). Handbook on animal-assisted therapy : theoretical foundations and guidelines for practice (3rd ed.). Amsterdam: Elsevier/Academic. pp. 49–57. ISBN 9780123814548. OCLC 652759283.

- Serpell JA. 2006. Animal-assisted interventions in historical perspective. In: Fine AH, ed. Handbook on Animal-Assisted Therapy: Theoretical Foundations and Guidelines for Practice. San Diego: Elsevier. p 3-17

- Serpell J (2000). "Animal Companions and Human Well-Being: An Historical Exploration of the Value of Human-Animal Relationships". Handbook on Animal-Assisted Therapy: Theoretical Foundations and Guidelines for Practice: 3–17.

- Velde BP, Cipriani J, Fisher G (2005). "Resident and therapist views of animal-assisted therapy: Implications for occupational therapy practice". Australian Occupational Therapy Journal. 52 (1): 43–50. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1630.2004.00442.x.

- Stanley Coren (2010), "Foreword", Handbook on Animal-Assisted Therapy, Academic Press, ISBN 978-0-12-381453-1

- Zilcha-Mano S, Mikulincer M, Shaver PR (November 2011). "Pet in the therapy room: an attachment perspective on Animal-Assisted Therapy". Attachment & Human Development. 13 (6): 541–61. doi:10.1080/14616734.2011.608987. PMID 22011099.

- Reichert E (1998). "Individual counseling for sexually abused children: A role for animals and storytelling". Child & Adolescent Social Work Journal. 15 (3): 177–185. doi:10.1023/A:1022284418096.

External links

- Assistance Animal State Laws - Michigan State University

- Disabilities and Medical Conditions - TSA (Transport Security Administration)

- Skloot, Rebecca (December 31, 2008) "Creature Comforts", The New York Times