Vaychi

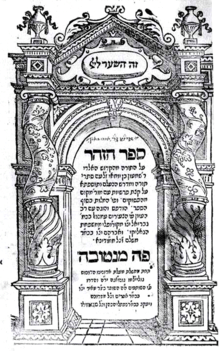

Vaychi, Vayechi or Vayhi (וַיְחִי — Hebrew for "and he lived," the first word of the parashah) is the twelfth weekly Torah portion (פָּרָשָׁה, parashah) in the annual Jewish cycle of Torah reading and the last in the Book of Genesis. It constitutes Genesis 47:28–50:26. The parashah tells of Jacob's request for burial in Canaan, Jacob's blessing of Joseph's sons Ephraim and Manasseh, Jacob's blessing of his sons, Jacob's death and burial, and Joseph's death.

It is the shortest weekly Torah portion in the Book of Genesis (although not in the Torah). It is made up of 4,448 Hebrew letters, 1,158 Hebrew words, 85 verses, and 148 lines in a Torah scroll (סֵפֶר תּוֹרָה, Sefer Torah).[1] Jews read it the twelfth Sabbath after Simchat Torah, generally in December or January.[2]

Readings

In traditional Sabbath Torah reading, the parashah is divided into seven readings, or עליות, aliyot. In the Masoretic Text of the Tanakh (Hebrew Bible), Parashah Vayechi has 12 "open portion" (פתוחה, petuchah) divisions (roughly equivalent to paragraphs, often abbreviated with the Hebrew letter פ (peh)). Parashah Vayechi has no "closed portion" (סתומה, setumah) divisions (abbreviated with the Hebrew letter ס (samekh)) within those open portion (פתוחה, petuchah) divisions. The first open portion (פתוחה, petuchah) spans the first three readings (עליות, aliyot). Ten further open portion (פתוחה, petuchah) divisions separate Jacob's blessings for his sons in the fifth and sixth readings (עליות, aliyot). The final, twelfth open portion (פתוחה, petuchah) spans the concluding sixth and seventh readings (עליות, aliyot).[3]

First reading — Genesis 47:28–48:9

In the first reading (עליה, aliyah), Jacob lived in Egypt 17 years, and lived to be 147 years old.[4] When Jacob's death drew near, he called his son Joseph and asked him to put his hand under Jacob's thigh and swear not to bury him in Egypt, but to bury him with his father and grandfather.[5] Joseph agreed, but Jacob insisted that he swear to, and so he did, and Jacob bowed.[6] Later, when one told Joseph that his father was sick, Joseph took his sons Manasseh and Ephraim to see him.[7] Jacob sat up and told Joseph that God appeared to him at Luz, blessed him, and told him that God would multiply his descendants and give them that land forever.[8] Jacob adopted Joseph's sons as his own and granted them inheritance with his own sons.[9] Jacob recalled how when he came from Paddan, Rachel died on the way, and he buried her on the way to Ephrath, near Bethlehem.[10] Jacob saw Joseph's sons and asked who they were, and Joseph told him that they were the sons whom God had given him in Egypt, so Jacob asked Joseph to bring them near so that he might bless them.[11] The first reading (עליה, aliyah) ends here.[12]

Second reading — Genesis 48:10–16

In the second reading (עליה, aliyah), Jacob's sight had dimmed with age, so Joseph brought his sons near, and Jacob kissed them and embraced them.[13] Jacob told Joseph that he had not thought to see his face, and now God had let him see his children, as well.[14] Joseph took them from between his knees, bowed deeply, and brought them to Jacob, with Ephraim in his right hand toward Jacob's left hand, and Manasseh in his left hand toward Jacob's right hand.[15] But Jacob laid his right hand on Ephraim, the younger, and his left hand on Manasseh, the firstborn, and prayed that God bless the lads, let Jacob's name be named in them, and let them grow into a multitude.[16] The second reading (עליה, aliyah) ends here.[17]

Third reading — Genesis 48:17–22

In the third reading (עליה, aliyah), it displeased Joseph that Jacob laid his right hand on Ephraim, and he lifted Jacob's right hand to move it to Manasseh the firstborn, but Jacob refused, saying that Manasseh would also become a great people, but his younger brother would be greater.[18] Jacob blessed them, saying Israel would bless by invoking God to make one like Ephraim and as Manasseh.[19] Jacob told Joseph that he was dying, but God would be with him and bring him back to the land of his fathers, and Jacob had given him a portion (shechem) above his brothers, which he took from the Amorites with his sword and bow.[20] The third reading (עליה, aliyah) and the first open portion (פתוחה, petuchah) end here.[21]

Fourth reading — Genesis 49:1–18

In the fourth reading (עליה, aliyah), Jacob gathered his sons and asked them to listen to what would befall them in time.[22] Jacob called Reuben his firstborn, his might, and the first-fruits of his strength; unstable as water, he would not have the best because he defiled his father's bed.[23] The second open portion (פתוחה, petuchah) ends here.[24]

In the continuation of the reading (עליה, aliyah), Jacob called Simeon and Levi brothers in violence, prayed that his soul not come into their council — for in their anger they slew men and beasts — and cursed their descendants to be scattered throughout Israel.[25] The third open portion (פתוחה, petuchah) ends here.[26]

In the continuation of the reading (עליה, aliyah), Jacob called Judah a lion's whelp and told him that he would dominate his enemies, his brothers would bow before him, and his descendants would rule as long as men came to Shiloh.[27] Binding his foal to the vine, he would wash his garments in wine, and his teeth would be white with milk.[28] The fourth open portion (פתוחה, petuchah) ends here.[29]

In the continuation of the reading (עליה, aliyah), Jacob foretold that Zebulun's descendants would dwell at the shore near Sidon, and would work the ships.[30] The fifth open portion (פתוחה, petuchah) ends here.[29]

As the reading (עליה, aliyah) continues, Jacob called Issachar a large-boned donkey couching between the sheep-folds, he bowed his shoulder to work, and his descendants would dwell in a pleasant land.[31] The sixth open portion (פתוחה, petuchah) ends here.[32]

In the continuation of the reading (עליה, aliyah), Jacob called Dan a serpent in the road that bites the horse's heels, and he would judge his people.[33] Jacob interjected that he longed for God's salvation.[34] The fourth reading (עליה, aliyah) and the seventh open portion (פתוחה, petuchah) end here.[35]

Fifth reading — Genesis 49:19–26

In the fifth reading (עליה, aliyah), Jacob foretold that raiders would raid Gad, but he would raid on their heels.[36] The eighth open portion (פתוחה, petuchah) ends here.[35]

In the continuation of the reading (עליה, aliyah), Jacob foretold that Asher's bread would be the richest, and he would yield royal dainties.[37] The ninth open portion (פתוחה, petuchah) ends here.[35]

As the reading (עליה, aliyah) continues, Jacob called Naphtali a hind let loose, and he would give good words.[38] The tenth open portion (פתוחה, petuchah) ends here.[35]

In the continuation of the reading (עליה, aliyah), Jacob called Joseph a fruitful vine by a fountain whose branches ran over the wall, archers shot at him, but his bow remained firm; Jacob blessed him with blessings of heaven above and the deep below, blessings of the breasts and womb, and mighty blessings on the head of the prince among his brethren.[39] The fifth reading (עליה, aliyah) and the eleventh open portion (פתוחה, petuchah) end here.[40]

Sixth reading — Genesis 49:27–50:20

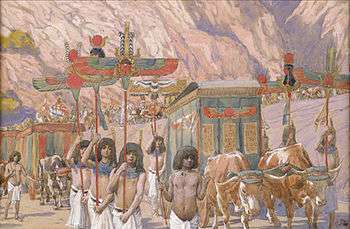

In the long sixth reading (עליה, aliyah), Jacob called Benjamin a ravenous wolf that devours its prey.[41] The editor summarises: "these are the twelve tribes".[42] And Jacob charged his sons to bury him with his fathers in the cave of Machpelah that Abraham bought and where they buried Abraham and Sarah, Isaac and Rebekah, and where he buried Leah.[43] And then Jacob gathered his feet into his bed and died.[44] Joseph kissed his father's face and wept.[45] Joseph commanded the physicians to embalm Jacob, and they did so over the next 40 days, and the Egyptians wept for Jacob 70 days.[46] Thereafter, Joseph asked Pharaoh's courtiers to tell Pharaoh that Jacob had made Joseph swear to bury him in the land of Canaan and ask that he might go up, bury his father, and return.[47] Pharaoh consented, and Joseph went up with all Pharaoh's court, Egypt's elders, chariots, horsemen, and all Joseph's relatives, leaving only the little ones and the flocks and herds behind in the land of Goshen.[48] At the threshing-floor of Atad, beyond the Jordan River, they mourned for his father seven days, and the Canaanites remarked at how grievous the mourning was for the Egyptians, and thus the place was named Abel-mizraim.[49] Jacob's sons carried out his command and buried him in the cave of Machpelah, and the funeral party returned to Egypt.[50] With Jacob's death, Joseph's brothers grew concerned that Joseph would repay them for the evil that they had done, and they sent Joseph a message that Jacob had commanded him to forgive them.[51] When the brothers spoke to Joseph, he wept, and his brothers fell down before him and declared that they were his bondmen.[52] Joseph told them not to fear, for he was not God, and even though they had intended him evil, God meant it for good, to save many people.[53] The sixth reading (עליה, aliyah) ends here.[54]

Seventh reading — Genesis 50:21–26

In the seventh reading (עליה, aliyah), Joseph spoke kindly to them, comforted them, and committed to sustain them and their little ones.[55] Joseph lived 110 years, saw Ephraim's children of the third generation, and grandchildren of Manasseh were born on Joseph's knees.[56] Joseph told his brothers that he was dying, but God would surely remember them and bring them out of Egypt to the land that God had sworn to Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob.[57] Joseph made the children of Israel swear to carry his bones to that land.[58] So Joseph died, and they embalmed him, and put him in a coffin in Egypt.[59] The seventh reading (עליה, aliyah), the twelfth open portion (פתוחה, petuchah), the parashah, and the Book of Genesis all end here.[60]

Readings according to the triennial cycle

Jews who read the Torah according to the triennial cycle of Torah reading read the parashah according to the following schedule:[61]

| Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2019–2020, 2022–2023, . . . | 2020–2021, 2023–2024, . . . | 2021–2022, 2024–2025, . . . | |

| Reading | 47:28–48:22 | 49:1–49:26 | 49:27–50:26 |

| 1 | 47:28–31 | 49:1–4 | 49:27–30 |

| 2 | 48:1–3 | 49:5–7 | 49:31–33 |

| 3 | 48:4–9 | 49:8–12 | 50:1–6 |

| 4 | 48:10–13 | 49:13–15 | 50:7–9 |

| 5 | 48:14–16 | 49:16–18 | 50:10–14 |

| 6 | 48:17–19 | 49:19–21 | 50:15–20 |

| 7 | 48:20–22 | 49:22–26 | 50:21–26 |

| Maftir | 48:20–22 | 49:22–26 | 50:23–26 |

In ancient parallels

The parashah has parallels in these ancient sources:

Genesis chapter 50

Professor Gerhard von Rad of Heidelberg University in the mid-20th-century argued that the Joseph narrative is closely related to earlier Egyptian wisdom writings.[62] Von Rad likened the theology of Joseph's statement to his brothers in Genesis 50:20, “And as for you, you meant evil against me; but God meant it for good, to bring to pass, as it is this day, to save many people alive,” to that of Amenemope, who said, “That which men propose is one thing; what God does is another,” and “God’s life is achievement, but man’s is denial.”[63]

In inner-biblical interpretation

The parashah has parallels or is discussed in these Biblical sources:[64]

Genesis chapter 49

Genesis 49:3–27, Deuteronomy 33:6–25, and Judges 5:14–18 present parallel listings of the Twelve Tribes, presenting contrasting characterizations of their relative strengths:

| Tribe | Genesis 49 | Deuteronomy 33 | Judges 5 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reuben | Jacob's first-born, Jacob's might, the first-fruits of Jacob's strength, the excellency of dignity, the excellency of power; unstable as water, he would not have the excellency because he mounted his father's bed and defiled it | let him live and not die and become few in number | among their divisions were great resolves of heart; they sat among the sheepfolds to hear the piping for the flocks, and did not contribute; at their divisions was great soul-searching |

| Simeon | brother of Levi, weapons of violence were their kinship; let Jacob's soul not come into their council, to their assembly, for in their anger they slew men, in their self-will they hewed oxen; cursed was their fierce anger and their cruel wrath, Jacob would divide and scatter them in Israel | not mentioned | not mentioned |

| Levi | brother of Simeon, weapons of violence were their kinship; let Jacob's soul not come into their council, to their assembly, for in their anger they slew men, in their self-will they hewed oxen; cursed was their fierce anger and their cruel wrath, Jacob would divide and scatter them in Israel | his Thummim and Urim would be with God; God proved him at Massah, with whom God strove at the waters of Meribah; he did not acknowledge his father, mother, brothers, or children; observed God's word, and would keep God's covenant; would teach Israel God's law; would put incense before God, and whole burnt-offerings on God's altar; God bless his substance, and accept the work of his hands; smite the loins of his enemies | not mentioned |

| Judah | his brothers would praise him, his hand would be on the neck of his enemies, his father's sons would bow down before him; a lion's whelp, from the prey he is gone up, he stooped down, he couched as a lion and a lioness, who would rouse him? the scepter would not depart from him, nor the ruler's staff from between his feet, as long as men come to Shiloh, to him would the obedience of the peoples be; binding his foal to the vine and his ass's colt to the choice vine, he washes his garments in wine, his eyes would be red with wine, and his teeth white with milk | God hear his voice, and bring him in to his people; his hands would contend for him, and God would help against his adversaries | not mentioned |

| Zebulun | would dwell at the shore of the sea, would be a shore for ships, his flank would be upon Zidon | he would rejoice in his going out, with Issachar he would call peoples to the mountain; there they would offer sacrifices of righteousness, for they would suck the abundance of the seas, and the hidden treasures of the sand | they that handle the marshal's staff; jeopardized their lives for Israel |

| Issachar | a large-boned ass, couching down between the sheep-folds, he saw a good resting-place and the pleasant land, he bowed his shoulder to bear and became a servant under task-work | he would rejoice in his tents, with Zebulun he would call peoples to the mountain; there they would offer sacrifices of righteousness, for they would suck the abundance of the seas, and the hidden treasures of the sand | their princes were with Deborah |

| Dan | would judge his people, would be a serpent in the way, a horned snake in the path, that bites the horse's heels, so that his rider falls backward | a lion's whelp, that leaps forth from Bashan | sojourned by the ships, and did not contribute |

| Gad | a troop would troop upon him, but he would troop upon their heel | blessed be God Who enlarges him; he dwells as a lioness, and tears the arm and the crown of the head; he chose a first part for himself, for there a portion of a ruler was reserved; and there came the heads of the people, he executed God's righteousness and ordinances with Israel | Gilead stayed beyond the Jordan and did not contribute |

| Asher | his bread would be fat, he would yield royal dainties | blessed above sons; let him be the favored of his brothers, and let him dip his foot in oil; iron and brass would be his bars; and as his days, so would his strength be | dwelt at the shore of the sea, abided by its bays, and did not contribute |

| Naphtali | a hind let loose, he gave goodly words | satisfied with favor, full with God's blessing, would possess the sea and the south | were upon the high places of the field of battle |

| Joseph | a fruitful vine by a fountain, its branches run over the wall, the archers have dealt bitterly with him, shot at him, and hated him; his bow abode firm, and the arms of his hands were made supple by God, who would help and bless him with blessings of heaven above, the deep beneath, the breast and the womb; Jacob's blessings, mighty beyond the blessings of his ancestors, would be on his head, and on the crown of the head of the prince among his brothers | blessed of God was his land; for the precious things of heaven, for the dew, and for the deep beneath, and for the precious things of the fruits of the sun, and for the precious things of the yield of the moons, for the tops of the ancient mountains, and for the precious things of the everlasting hills, and for the precious things of the earth and the fullness thereof, and the good will of God; the blessing would come upon the head of Joseph, and upon the crown of the head of him that is prince among his brothers; his firstling bullock, majesty was his; and his horns were the horns of the wild-ox; with them he would gore all the peoples to the ends of the earth; they were the ten thousands of Ephraim and the thousands of Manasseh | out of Ephraim came they whose root is in Amalek |

| Benjamin | a ravenous wolf, in the morning he devoured the prey, at evening he divided the spoil | God's beloved would dwell in safety by God; God covered him all the day, and dwelt between his shoulders | came after Ephriam |

Jacob's blessing of Reuben in Genesis 49:4, depriving Reuben of the blessing of the firstborn, because he went up on Jacob's bed and defiled it, recalls the report of Genesis 35:22 that Reuben lay with Bilhah, Jacob's concubine, and Jacob heard of it.

Genesis chapter 50

When Joseph in Genesis 50:20 told his brothers that they meant evil against him, but God meant it for good to save the lives of many people, he echoed his explanation in Genesis 45:5 that God sent him to Egypt before his brothers to preserve life. Similarly, Psalms 105:16–17 reports that God called a famine upon the land and sent Joseph before the children of Israel.

Von Rad likened the theology of Joseph's statement to his brothers in Genesis 50:20, “And as for you, you meant evil against me; but God meant it for good,” to that of Proverbs 16:9, “A man's heart devises his way; but the Lord directs his steps”; Proverbs 19:21, “There are many devices in a man's heart; but the counsel of the Lord, that shall stand”; Proverbs 20:24, “A man's goings are of the Lord; how then can man look to his way?”; and Proverbs 21:30–31, “There is no wisdom nor understanding nor counsel against the Lord. The horse is prepared against the day of battle; but victory is of the Lord.”[63]

In classical rabbinic interpretation

The parashah is discussed in these rabbinic sources from the era of the Mishnah and the Talmud:[65]

.jpg)

Genesis Chapter 47

Rabbi Joḥanan taught that trouble follows whenever Scripture employs the word וַיֵּשֶׁב, vayeishev, meaning "and he settled." Thus "Israel settled" in Genesis 47:27 presaged trouble in the report of Genesis 47:29 that Israel's death drew near.[66]

Reading the words of Genesis 47:29, "and he called his son Joseph," a Midrash asked why Jacob did not call Reuben or Judah, as Reuben was the firstborn and Judah was king. Yet Jacob disregarded them and called Joseph, because Joseph had the means of fulfilling Jacob's wishes.[67]

Rabbi Eliezer taught that in the hour of Jacob's death, he called to his son Joseph, and adjured him to swear to Jacob by the covenant of circumcision that Joseph would take Jacob up to the burial-place of his fathers in the Cave of Machpelah. Rabbi Eliezer explained that before the giving of the Torah, the ancients used to swear by the covenant of circumcision, as Jacob said in Genesis 47:29, "Put, I pray you, your hand under my thigh." And Rabbi Eliezer taught that Joseph kept the oath and did as he swore, as Genesis 50:7 reports.[68]

A Midrash asked why Jacob told Joseph in Genesis 47:29, "Bury me not, I pray, in Egypt." The Midrash suggested that it was because Egypt would eventually be smitten with vermin (in the Plagues of Egypt), which would swarm about Jacob's body. Alternatively, the Midrash suggested that it was so that Egyptians should not make Jacob an object of idolatrous worship. For just as idolaters will be punished, so will their idols too be punished, as Exodus 12:12 says, "And against all the gods of Egypt I will execute judgments."[69]

Reading Genesis 47:29, "Bury me not, I pray, in Egypt", a Midrash explained that Jacob wanted his bones to be carried away from Egypt, lest Jacob's descendants remain there, arguing that Egypt must be a holy land, or Jacob would not have been buried there. The Midrash taught that Jacob also wanted his family quickly to rejoin him in the Land of Israel, as Jacob trusted God to fulfill God's promise in Malachi 3:24, "He shall turn the heart of the fathers to the children, and the heart of the children to their fathers." Alternatively, a Midrash taught that Jacob feared that when God afflicted the Egyptians with the Plagues, they would surround Jacob's sepulcher and beseech him to intercede for them. If he did intercede, he would be helping God's enemies. If he did not, he would cause God's Name to be profaned by the Egyptians, who would call Jacob's God inefficacious. Alternatively, a Midrash taught that God promised Jacob in Genesis 28:13, "The land whereon you lie, to you will I give it, and to your seed," (and this implied) that if Jacob lay in the land, it would be his, but if not, it would not be his.[70]

Alternatively, reading Genesis 47:29, "Bury me not, I pray, in Egypt", a Midrash explained that Psalm 26:9, "Gather not my soul with sinners," alludes to the Egyptians, with whom Jacob sought not to be buried.[71] Similarly, the Gemara taught that Jews have a rule that a righteous person may not be buried near a wicked person.[72]

Reading Jacob's request in Genesis 47:30, "You shall carry me out of Egypt and bury me in their burying-place", the Jerusalem Talmud asked why Jacob went to such lengths, as Jacob would be Jacob wherever he was laid to rest. What would be lacking if he were buried elsewhere? Rabbi Shimon ben Lakish explained in the name of Bar Kappara that Israel is the land whose dead will be resurrected first in the Messianic era.[73]

Karna deduced from Genesis 47:30 that Jacob sought burial in Israel to ensure his resurrection. Karna reasoned that Jacob knew that he was an entirely righteous man, and that the dead outside Israel will also be resurrected, so Jacob must have troubled his sons to carry him to Canaan because he feared that he might be unworthy to travel through tunnels to the site of resurrection in Israel. Similarly, Rabbi Hanina explained that the same reason prompted Joseph to seek burial in Israel in Genesis 50:25.[74]

Rav Judah cited Genesis 47:30 to support the proposition that gravediggers must remove surrounding earth when they rebury a body. Rav Judah interpreted the verse to mean "carry with me [earth] of Egypt."[75]

Rabbi Elazar read Genesis 47:31 to report that Jacob bowed to Joseph because Joseph was in power. The Gemara read Jacob's action to illustrate a saying then popular: "When the fox has its hour, bow down to it." That is, even though one would ordinarily expect the lion to be the king of beasts, when the fox has its turn to rule, one should bow to it as well. The Gemara thus viewed Joseph as the fox, to whom, in his day, even the senior Jacob bowed down.[76]

A Midrash read Genesis 47:31 to teach that Jacob gave thanks for Leah, for Genesis 47:31 says, "And Israel bowed down [in thanksgiving] for the bed's head," and the Midrash read Leah (as the first who bore Jacob children) to be the head of Jacob's bed.[77]

Genesis Chapter 48

Interpreting Genesis 48:1, the Gemara taught that until the time of Jacob, there was no illness (as one lived one's allotted years in health and then died suddenly). Then Jacob came and prayed, and illness came into being, as Genesis 48:1 reports, "And one told Joseph, ‘Behold, your father is sick'" (reporting sickness for the first time in the Torah).[78] Similarly, the Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer reported that from the creation of the Heaven and earth until then, no person had ever become ill. Rather, they would remain fit until the time they were to die. Then, wherever they would happen to be, they would sneeze, and their souls would depart through their noses. But then Jacob prayed, seeking mercy from God, asking that God not take his soul until he had an opportunity to charge his sons and all his household. And then, as Genesis 48:1 reports, "And one told Joseph, ‘Behold, your father is sick.'" Therefore, a person is duty bound to say "life!" after another sneezes.[79]

Interpreting Genesis 48:5–6, the Gemara examined the consequences of Jacob's blessing of Ephraim and Manasseh. Rav Aha bar Jacob taught that a tribe that had an inheritance of land was called a "congregation," but a tribe that had no possession was not a "congregation." Thus Rav Aha bar Jacob taught that the tribe of Levi was not called a "congregation." The Gemara questioned Rav Aha's teaching, asking whether there would then be fewer than 12 tribes. Abaye replied quoting Jacob's words in Genesis 48:5: "Ephraim and Manasseh, even as Reuben and Simeon, shall be mine." But Rava interpreted the words "They shall be called after the name of their brethren in their inheritance" in Genesis 48:6 to show that Ephraim and Manasseh were thereafter regarded as comparable to other tribes only in regard to their inheritance of the land, not in any other respect. The Gemara challenged Rava's interpretation, noting that Numbers 2:18–21 mentions Ephraim and Manasseh separately as tribes in connection with their assembling around the camp by their banners. The Gemara replied to its own challenge by positing that their campings were like their possessions, in order to show respect to their banners. The Gemara persisted in arguing that Ephraim and Manasseh were treated separately by noting that they were also separated with regard to their princes. The Gemara responded that this was done in order to show honor to the princes and to avoid having to choose the prince of one tribe to rule over the other. 1 Kings 8:65 indicates that Solomon celebrated seven days of dedication of the Temple in Jerusalem, and Moses celebrated twelve days of dedication of the Tabernacle instead of seven in order to show honor to the princes and to avoid having to choose the prince of one tribe over the other.[80]

Rav Judah said in the name of Samuel that Genesis 48:5, where grandchildren are equated with children, serves to remind the reader that cursing a husband's parents in the presence of the husband's children is just as bad as cursing them in the husband's presence. Rabbah said that an example of such a curse would be where a woman told her husband's son, "May a lion devour your grandfather."[81]

Rav Papa cited Genesis 48:5 to demonstrate that the word "noladim," meaning "born," applies to lives already in being, not just to children to be born in the future, as "nolad" appears to refer in 1 Kings 13:2.[82]

A Baraita used Genesis 48:6 to illustrate the effect of the law of levirate marriage, where a brother marries his dead brother's wife and raises a child in the dead brother's name. Just as in Genesis 48:6 Ephraim and Manasseh were to inherit from Jacob, so in levirate marriage the brother who marries his dead brother's wife and their children thereafter were to inherit from the dead brother.[83]

The Gemara noted that in Genesis 48:7, Jacob exclaimed about Rachel's death as a loss to him, supporting the proposition stated by a Baraita that the death of a woman is felt by none so much as by her husband.[84]

Rabbi Hama the son of Rabbi Hanina taught that our ancestors were never without a scholars' council. Abraham was an elder and a member of the scholars' council, as Genesis 24:1 says, "And Abraham was an elder (זָקֵן, zaken) well stricken in age." Eliezer, Abraham's servant, was an elder and a member of the scholars' council, as Genesis 24:2 says, "And Abraham said to his servant, the elder of his house, who ruled over all he had," which Rabbi Eleazar explained to mean that he ruled over — and thus knew and had control of — the Torah of his master. Isaac was an elder and a member of the scholars' council, as Genesis 27:1 says: "And it came to pass when Isaac was an elder (זָקֵן, zaken)." Jacob was an elder and a member of the scholars' council, as Genesis 48:10 says, "Now the eyes of Israel were dim with age (זֹּקֶן, zoken)." In Egypt they had the scholars' council, as Exodus 3:16 says, "Go and gather the elders of Israel together." And in the Wilderness, they had the scholars' council, as in Numbers 11:16, God directed Moses to "Gather . . . 70 men of the elders of Israel."[85]

Rabbi Joḥanan deduced from Genesis 48:15–16 that sustenance is more difficult to achieve than redemption. Rabbi Joḥanan noted that in Genesis 48:16 a mere angel sufficed to bring about redemption, whereas Genesis 48:16 reported that God provided sustenance.[86]

Rabbi Jose son of Rabbi Hanina deduced from Genesis 48:16 that the descendants of Joseph did not have to fear the evil eye. In Genesis 48:16, Jacob blessed Joseph's descendants to grow like fishes. Rabbi Jose son of Rabbi Hanina interpreted that just the eye cannot see fish in the sea that are covered by water, so the evil eye would have no power to reach Joseph's descendants.[87]

Interpreting Genesis 48:21, Rabbi Jose's nephew taught that as he was dying, Jacob gave his sons three signs by which his descendants might recognize the true redeemer: (1) he would come using, as Jacob did, the word "I" (אָנֹכִי, anoki), (2) he would appoint elders for the people, and (3) he would say to the people, "God will remember you" (פָּקֹד, pakod, as Joseph did in Genesis 50:24). Rabbi Hunia omitted the word "I" (אָנֹכִי, anoki) and substituted God's special secret name (שם המפורש, the Shem HaMephorash).[88]

The Gemara read the reference in Genesis 48:22 to "one portion above your brothers" to mean that like a firstborn son, Joseph received a double portion. Rav Papa asked Abaye whether perhaps Jacob merely gave Joseph an extra palm tree. Abaye answered that Genesis 48:5 demonstrated that Jacob intended that Joseph would get two full portions "even as Reuben and Simeon." Rabbi Helbo asked Rabbi Samuel bar Nahmani why Jacob took the firstborn's birthright from Reuben and gave it to Joseph. The Gemara answered by citing Genesis 49:4 to show that Reuben lost the birthright when he defiled Jacob's bed. The Gemara asked why Joseph benefited from Reuben's disqualification. Rabbi Samuel bar Nahmani responded with a parable of an orphan who was brought up by an adoptive father, and when he became rich he chose to give to his adoptive father from his wealth. Similarly, because Joseph cared for Jacob, Jacob chose to give to Joseph. Rabbi Helbo challenged that reason, arguing instead that Rabbi Jonathan said that Rachel should have borne the firstborn, as indicated by the naming of Joseph in Genesis 37:2, and God restored the right of the firstborn to Rachel because of her modesty. And a Baraita read the reference in Genesis 48:22 to "my sword and . . . my bow" to mean Jacob's spiritual weapons, interpreting "my sword" to mean prayer and "my bow" to mean supplication.[89]

Rabbi Joḥanan said that he would sit at the gate of the bathhouse (mikvah), and when Jewish women came out they would look at him and have children as handsome as he was. The Rabbis asked him whether he was not afraid of the evil eye for being so boastful. He replied that the evil eye has no power over the descendants of Joseph, citing the words of Genesis 49:22, "Joseph is a fruitful vine, a fruitful vine above the eye (alei ayin)." Rabbi Abbahu taught that one should not read alei ayin ("by a fountain"), but olei ayin ("rising over the eye"). Rabbi Judah (or some say Rabbi Jose) son of Rabbi Hanina deduced from the words "And let them (the descendants of Joseph) multiply like fishes (ve-yidgu) in the midst of the earth" in Genesis 48:16 that just as fish (dagim) in the sea are covered by water and thus the evil eye has no power over them, so the evil eye has no power over the descendants of Joseph. Alternatively, the evil eye has no power over the descendants of Joseph because the evil eye has no power over the eye that refused to enjoy what did not belong to it — Potiphar's wife — as reported in Genesis 39:7–12.[90]

Genesis Chapter 49

The Sifre taught that Jacob demonstrated in Genesis 49 the model of how to admonish others when one is near death. The Sifre read Deuteronomy 1:3–4 to indicate that Moses spoke to the Israelites in rebuke. The Sifre taught that Moses rebuked them only when he approached death, and the Sifre taught that Moses learned this lesson from Jacob, who admonished his sons in Genesis 49 only when he neared death. The Sifre cited four reasons why people do not admonish others until the admonisher nears death: (1) so that the admonisher does not have to repeat the admonition, (2) so that the one rebuked would not suffer undue shame from being seen again, (3) so that the one rebuked would not bear ill will to the admonisher, and (4) so that the one may depart from the other in peace, for admonition brings peace. The Sifre cited as further examples of admonition near death: (1) when Abraham reproved Abimelech in Genesis 21:25, (2) when Isaac reproved Abimelech, Ahuzzath, and Phicol in Genesis 26:27, (3) when Joshua admonished the Israelites in Joshua 24:15, (4) when Samuel admonished the Israelites in 1 Samuel 12:34–35, and (5) when David admonished Solomon in 1 Kings 2:1.[91]

The Gemara explained that when Jews recite the Shema, they recite the words, "blessed be the name of God's glorious Kingdom forever and ever," quietly between the words, "Hear, O Israel: the Lord our God, the Lord is one," from Deuteronomy 6:4, and the words, "And you shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your might," from Deuteronomy 6:5, for the reason that Rabbi Shimon ben Lakish expounded when he explained what happened in Genesis 49:1. That verse reports, "And Jacob called to his sons, and said: ‘Gather yourselves together, that I may tell you what will befall you in the end of days.'" According to Rabbi Simeon, Jacob wished to reveal to his sons what would happen in the end of the days, but just then, the Divine Presence (שכינה, Shechinah) departed from him. So Jacob said that perhaps, Heaven forefend, he had fathered a son who was unworthy to hear the prophecy, just as Abraham had fathered Ishmael or Isaac had fathered Esau. But his sons answered him (in the words of Deuteronomy 6:4), "Hear O Israel, the Lord our God, the Lord is One," explaining that just as there was only One in Jacob's heart, so there was only One in their hearts. And Jacob replied, "Blessed be the name of God's glorious Kingdom forever and ever." The Rabbis considered that Jews might recite "Blessed be the name of God's glorious Kingdom forever and ever" aloud, but rejected that option, as Moses did not say those words in Deuteronomy 6:4–5. The Rabbis considered that Jews might not recite those words at all, but rejected that option, as Jacob did say the words. So the Rabbis ruled that Jews should recite the words quietly. Rabbi Isaac taught that the School of Rabbi Ammi said that one can compare this practice to that of a princess who smelled a spicy pudding. If she revealed her desire for the pudding, she would suffer disgrace; but if she concealed her desire, she would suffer deprivation. So her servants brought her pudding secretly. Rabbi Abbahu taught that the Sages ruled that Jews should recite the words aloud, so as not to allow heretics to claim that Jews were adding improper words to the Shema. But in Nehardea, where there were no heretics so far, they recited the words quietly.[92]

Interpreting Jacob's words "exceeding in dignity" in Genesis 49:3, a Midrash taught that Reuben should have received three portions in excess of his brothers — the birthright, priesthood, and royalty. But when Reuben sinned, the birthright was transferred to Joseph, the priesthood to Levi, and the royalty to Judah.[93]

The Rabbis of the Talmud disputed whether Reuben sinned. Rabbi Samuel bar Nahman said in Rabbi Jonathan's name that whoever maintains that Reuben sinned errs, for Genesis 35:22 says, "Now the sons of Jacob were twelve," teaching that they were all equal in righteousness. Rabbi Jonathan interpreted the beginning of Genesis 35:22, "and he lay with Bilhah his father's concubine," to teach that Reuben moved his father's bed from Bilhah's tent to Leah's tent, and Scripture imputes blame to him as though he had lain with her. Similarly, it was taught in a Baraita that Rabbi Simeon ben Eleazar said that the righteous Reuben was saved from sin. Rabbi Simeon ben Eleazar asked how Reuben's descendants could possibly have been directed to stand on Mount Ebal and proclaim in Deuteronomy 27:20, "Cursed be he who lies with his father's wife," if Reuben had sinned with Bilhah. Rabbi Simeon ben Eleazar interpreted Genesis 35:22, "and he lay with Bilhah his father's concubine," to teach that Reuben resented his mother Leah's humiliation, and did not want Rachel's maid Bilhah to join Rachel as a rival to Leah. So Reuben moved her bed. Others told that Reuben moved two beds, one of the Divine Presence (שכינה, Shechinah) and the other of his father, as Jacob set a couch for the Divine Presence in each of his wives' tents, and he spent the night where the Divine Presence came to rest. According to this view, one should read Genesis 49:4 to say, "Then you defiled my couch on which (the Divine Presence) went up." But the Gemara also reported disputes among the Tannaim on how to interpret the word "unstable (פַּחַז, pachaz)" in Genesis 49:4, where Jacob called Reuben, "unstable (פַּחַז, pachaz) as water." Several Rabbis read the word פַּחַז, pachaz, as an acronym, each letter indicating a word. Rabbi Eliezer interpreted Jacob to tell Reuben: "You were hasty (פ, paztah), you were guilty (ח, habtah), you disgraced (ז, zaltah)." Rabbi Joshua interpreted: "You overstepped (פ, pasatah) the law, you sinned (ח, hatata), you fornicated (ז, zanita)." Rabban Gamaliel interpreted: "You meditated (פ, pillaltah) to be saved from sin, you supplicated (ח, haltah), your prayer shone forth (ז, zarhah)." Rabban Gamaliel also cited the interpretation of Rabbi Eleazar the Modiite, who taught that one should reverse the word and interpret it: "You trembled (ז, zi'az'ata), you recoiled (ח, halita), your sin fled (פ, parhah) from you." Rava (or others say Rabbi Jeremiah bar Abba) interpreted: "You remembered (ז, zakarta) the penalty of the crime, you were grievously sick (ח, halita) through defying lust, you held aloof (פ, pirashta) from sinning."[94]

Rabbi Judah bar Simon taught that Moses later ameliorated the effects of Jacob's curse of Reuben in Genesis 49:4. Rabbi Judah bar Simon read Deuteronomy 28:6, “Blessed shall you be when you come in, and blessed shall you be when you go out,” to refer to Moses. Rabbi Judah bar Simon read “when you come in” to refer to Moses, because when he came into the world, he brought nearer to God Batya the daughter of Pharaoh (who by saving Moses from drowning merited life in the World to Come). And “blessed shall you be when you go out” also refers to Moses, for as he was departing the world, he brought Reuben nearer to his estranged father Jacob, when Moses blessed Reuben with the words “Let Reuben live and not die” in Deuteronomy 33:6 (thus gaining for Reuben the life in the World to Come and thus proximity to Jacob that Reuben forfeited when he sinned against his father in Genesis 35:22 and became estranged from him in Genesis 49:4).[95]

A Midrash taught that because Jacob said of the descendants of Simeon and Levi in Genesis 49:5, “To their assembly let my glory not be united,” referring to when they would assemble against Moses in Korah’s band, Numbers 16:1 traces Korah’s descent back only to Levi, not to Jacob.[96]

Similarly, the Gemara asked why Numbers 16:1 did not trace Korah's genealogy back to Jacob, and Rabbi Samuel bar Isaac answered that Jacob had prayed not to be listed amongst Korah's ancestors in Genesis 49:6, where it is written, "Let my soul not come into their council; unto their assembly let my glory not be united." "Let my soul not come into their council" referred to the spies, and "unto their assembly let my glory not be united" referred to Korah's assembly.[97]

It was taught in a Baraita that King Ptolemy brought together 72 elders and placed them in 72 separate rooms, without telling them why he had brought them together, and he asked each one of them to translate the Torah. God then prompted each one of them to conceive the same idea and write a number of cases in which the translation did not follow the Masoretic Text, including, for Genesis 49:6, "For in their anger they slew an ox, and in their wrath they dug up a stall" — writing "ox" instead of "man" to protect the reputation of Jacob's sons.[98]

It was taught in a Baraita that Issi ben Judah said that there are five verses in the Torah whose meaning they could not decide, including Genesis 49:6–7, which one can read, "And in their self-will they crippled oxen. Cursed be their anger, for it was fierce," or one can read, "And in their self-will they crippled the cursed oxen. Their anger was fierce." (In the latter reading, "the cursed oxen" refers to Shechem, a descendant of Canaan, whom Noah cursed in Genesis 9:25).[99]

A Midrash taught that the words "I will divide them in Jacob" in Genesis 49:7 foretold that scribes in synagogues would descend from the tribe of Simeon, and students and teachers of Mishnah would descend from the tribe of Levi, engaged in the study of the Torah in the houses of study. (These by their profession would thus be prevented from living in masses and would be scattered.)[100]

A Midrash taught that the words "Judah, you shall your brothers praise (יוֹדוּךָ, yoducha)" in Genesis 49:8 signify that because (in Genesis 38:26, in connection with his daughter-in-law Tamar) Judah confessed (the same word as "praise"), Judah's brothers would praise Judah in this world and in the World To Come (accepting descendants of Judah as their king). And in accordance with Jacob's blessing, 30 kings descended from Judah, for as Ruth 4:18 reports, David descended from Judah, and if one counts David, Solomon, Rehoboam, Abijah, Asa, Jehoshaphat and his successors until Jeconiah and Zedekiah (one finds 30 generations from Judah's son Perez to Zedekiah). And so the Midrash taught it shall be in the World To Come (the Messianic era), for as Ezekiel 37:25 foretells, "And David My servant shall be their prince forever."[100]

The Gemara told that the wise men of the enemy of the Jews Haman read Jacob's blessing of Judah in Genesis 49:8, "Your hand shall be on the neck of your enemies," to teach that Haman could not prevail against a descendant of Judah. Thus Esther 6:13 reports, "Then his (Haman's) wise men and Zeresh his wife said to him: ‘If Mordecai . . . be of the seed of the Jews (הַיְּהוּדִים, ha-Yehudim), you shall not prevail against him.'" (The word הַיְּהוּדִים, ha-Yehudim, can refer to both the Jews and the people of the tribe of Judah.) The Gemara reported that the wise men told Haman that if Mordecai came from another tribe, then Haman could prevail over him, but if he came from one of the tribes of Judah, Benjamin, Ephraim, or Manasseh, then Haman would not prevail over him. They deduced the strength of descendants of Judah from Genesis 49:8. And they deduced the strength of descendants of Benjamin, Ephraim, and Manasseh from Psalm 80:3, which says, "Before Ephraim and Benjamin and Manasseh stir up your might."[101]

The Midrash Tehillim expanded on Jacob's blessing of Judah in Genesis 49:8, “Your hand shall be on the neck of your enemies.” The Midrash Tehillim interpreted Psalm 18:41, “You have given me the necks of my enemies,” to allude to Judah, because Rabbi Joshua ben Levi reported an oral tradition that Judah slew Esau after the death of Isaac. Esau, Jacob, and all Jacob's children went to bury Isaac, as Genesis 35:29 reports, “Esau, Jacob, and his sons buried him,” and they were all in the Cave of Machpelah sitting and weeping. At last Jacob's children stood up, paid their respects to Jacob, and left the cave so that Jacob would not be humbled by weeping exceedingly in their presence. But Esau reentered the cave, thinking that he would kill Jacob, as Genesis 27:41 reports, “And Esau said in his heart: ‘Let the days of mourning for my father be at hand; then will I slay my brother Jacob.’” But Judah saw Esau go back and perceived at once that Esau meant to kill Jacob in the cave. Quickly Judah slipped after him and found Esau about to slay Jacob. So Judah killed Esau from behind. The neck of the enemy was given into Judah’s hands alone, as Jacob blessed Judah in Genesis 49:8 saying, “Your hand shall be on the neck of your enemies.” And thus David declared in Psalm 18:41, “You have given me the necks of my enemies,” as if to say that this was David's patrimony, since Genesis 49:8 said it of his ancestor Judah.[102]

Reading Genesis 49:9, Rabbi Joḥanan noted that the lion has six names[103] — אֲרִי, ari, twice in Genesis 49:9;[104] כְּפִיר, kefir;[105] לָבִיא, lavi in Genesis 49:9;[106] לַיִשׁ, laish;[107] שַׁחַל, shachal;[108] and שָׁחַץ, shachatz.[109]

The Gemara read Genesis 49:10, "The scepter shall not depart from Judah," to refer to the Exilarchs of Babylon, who ruled over Jews with scepters (symbols of the authority of a ruler appointed by the Government). And the Gemara read the term "lawgiver" in Genesis 49:10 to refers to the descendants of Hillel in the Land of Israel who taught the Torah in public. The Gemara deduced from this that an authorization held from the Exilarch in Babylonia held good in both Babylonia and the Land of Israel.[110]

The School of Rabbi Shila read the words of Genesis 49:10, "until Shiloh come," to teach that "Shiloh" is the name of the Messiah. And Rabbi Joḥanan taught that the world was created only for the sake of the Messiah.[111]

The Gemara taught that if one who sees a choice vine in a dream may look forward to seeing the Messiah, since Genesis 49:11 says, "Binding his foal to the vine and his donkey's colt to the choice vine," and Genesis 49:11 was thought to refer to the Messiah.[112]

When Rav Dimi came from the Land of Israel to Babylon, he taught that Genesis 49:11–12 foretold the wonders of the Land of Israel. He taught that the words of Genesis 49:11, "Binding his foal (עִירֹה, iro) to the vine," foretold that there will not be a vine in the Land of Israel that does not require everyone in a city (עִיר, ir) to harvest. He taught that the words of Genesis 49:11, "And his donkey's colt into the choice vine (שֹּׂרֵקָה, soreikah)," foretold that there would not even be a wild tree (סרק, serak) in the Land of Israel that would not produce enough fruit for two donkeys. In case one might imagine that the Land would not contain wine, Genesis 49:11 explicitly said, "He washes his garments in wine." In case one should say that it would not intoxicate, Genesis 49:11 states, "His vesture (סוּתֹה, susto, a cognate of hasasah, "enticement")." In case one might think that it would be tasteless, Genesis 49:12 states, "His eyes shall be red (חַכְלִילִי, chachlili) with wine," teaching that any palate that will taste it says, "To me, to me (לִי לִי, li li)." And in case one might say that it would suitable for young people but not for old, Genesis 49:12 states, "And his teeth white with milk," which Rav Dimi read not as, "white teeth (וּלְבֶן-שִׁנַּיִם, uleven shinayim)," but as, "To one who is advanced in years (לְבֶן-שָׁנִים, leven shanim)." Rav Dimi taught that the plain meaning of Genesis 49:12 conveyed that the congregation of Israel asked God to wink to them with God's eyes, which would be sweeter than wine, and show God's teeth, which would be sweeter than milk. The Gemara taught that this interpretation thus provided support for Rabbi Joḥanan, who taught that the person who smiles an affectionate, toothy smile to a friend is better than one who gives the friend milk to drink. For Genesis 49:12 says, "And his teeth white with milk," which Rabbi Joḥanan read not as "white teeth (לְבֶן-שִׁנַּיִם, leven shinayim)," but as, "showing the teeth (לְבון-שִׁנַּיִם, libun shinayim)."[113]

The Gemara taught that a certain man used to say that by the seashore thorn bushes are cypresses. (That is, the thorn bushes there were as attractive as cypresses elsewhere.) They investigated and found that he descended from Zebulun, for Genesis 49:13 says, "Zebulun shall dwell at the haven of the sea."[114]

.jpg)

Rabbi Levi considered the words "Zebulun['s] . . . boundary shall be upon Zidon" in Genesis 49:13, but since Sidon is in Asher's territory, Rabbi Levi concluded that the verse alludes to Zebulun's most distinguished descendant, Jonah, and deduced that Jonah's mother must have been from Sidon and the tribe of Asher.[115]

Rabbi Joḥanan taught that the words "and he lay with her that night" in Genesis 30:16, in which the word hu appears in an unusual locution, indicate that God assisted in causing Issachar's conception. Rabbi Joḥanan found in the words "Issachar is a large-boned donkey" in Genesis 49:14 an indication that Jacob's donkey detoured to Leah's tent, helping to cause Issachar's birth.[116]

Rabbi Joḥanan taught in the name of Rabbi Simeon bar Yochai that Genesis 49:14 and 49:22 help to show the value of Torah study and charity. Rabbi Joḥanan deduced from Isaiah 32:20, "Blessed are you who sow beside all waters, who send forth the feet of the ox and the donkey," that whoever engages in Torah study and charity is worthy of the inheritance of two tribes, Joseph and Issachar (as Deuteronomy 33:17 compares Joseph to an ox, and Genesis 49:14 compares Issachar to a donkey). Rabbi Joḥanan equated "sowing" with "charity," as Hosea 10:12 says, "Sow to yourselves in charity, reap in kindness." And Rabbi Joḥanan equated "water" with "Torah," as Isaiah 55:1 says, "Everyone who thirsts, come to the waters (that is, Torah)." Whoever engages in Torah study and charity is worthy of a canopy — that is, an inheritance — like Joseph, for Genesis 49:22 says, "Joseph is a fruitful bough . . . whose branches run over the wall." And such a person is also worthy of the inheritance of Issachar, as Genesis 49:14 says, "Issachar is a strong donkey" (which the Targum renders as rich with property). The Gemara also reported that some say that the enemies of such a person will fall before him as they did for Joseph, as Deuteronomy 33:17 says, "With them he shall push the people together, to the ends of the earth." And such a person is worthy of understanding like Issachar, as 1 Chronicles 12:32 says, "of the children of Issachar . . . were men who had understanding of the times to know what Israel ought to do."[117]

Citing Genesis 49:14, Rabbi Samuel bar Nahmani said in the name of Rabbi Jonathan that when a wife summons a husband to his marital duty, they will have children such as were not to be found even in the generation of Moses. For with regard to the generation of Moses, Deuteronomy 1:13 says, "Take wise men, and understanding and known among your tribes, and I will make them rulers over you." But Deuteronomy 1:15 says, "So I took the chiefs of your tribes, wise men and known," without mentioning "understanding" (implying that Moses could not find men with understanding). And Genesis 49:14 says, "Issachar is a large-boned donkey" (alluding to the Midrash that Leah heard Jacob's donkey, and so came out of her tent to summon Jacob to his marital duty, as reported in Genesis 30:16). And 1 Chronicles 12:32 says, "of the children of Issachar . . . were men who had understanding of the times to know what Israel ought to do." But the Gemara limited the teaching of Rabbi Samuel bar Nahmani in the name of Rabbi Jonathan by counseling that such behavior is virtuous only when the wife ingratiates herself to her husband without making brazen demands.[118]

The Gemara taught that a certain man insisted on going to court in every dispute. The Sages taught said that this proved that he descended from Dan, for Genesis 49:16 can be read, "Dan shall enter into judgment with his people, as one of the tribes of Israel."[119]

Rabbi Hama the son of Rabbi Hanina taught that the words of Judges 13:25, "And the spirit of the Lord began to move him (Samson) in Mahaneh-dan, between Zorah and Eshtaol", showed Jacob's prophecy becoming fulfilled. For in Genesis 49:17, Jacob foretold, "Dan shall be a serpent in the way." (Genesis 49:17 thus alluded to Samson, who belonged to the tribe of Dan and adopted the tactics of a serpent in fighting the Philistines.)[120] Rabbi Joḥanan taught that Samson judged Israel in the same manner as God, as Genesis 49:16 says, "Dan shall judge his people as One" (and God is One).[121] Rabbi Joḥanan also said that Samson was lame in both legs, as Genesis 49:17 says, "Dan shall be a serpent in the way, an adder (שְׁפִיפֹן, shefifon) in the path." (שְׁפִיפֹן, shefifon, evokes a doubling of the word שֶׁפִי, shefi, from the root שוף, "to dislocate.")[122]

Reading the words of Genesis 49:18, "I wait for Your salvation, O God," Rabbi Isaac taught that everything is bound up with waiting, hoping. Suffering, the sanctification of the Divine Name, the merit of the Ancestors, and the desire of the World To Come are all bound up with waiting. Thus Isaiah 26:8 says, "Yea, in the way of Your judgments, O Lord, have we waited for You," which alludes to suffering. The words of Isaiah 26:8, "To Your name," allude to the sanctification of the Divine Name. The words of Isaiah 26:8, "And to Your memorial," allude to ancestral merit. And the words of Isaiah 26:8, "The desire of our soul," allude to the desire for the future world. Grace comes through hope, as Isaiah 33:2 says, "O Lord, be gracious to us; we have waited (hoped) for You." Forgiveness comes through hope, as Psalm 130:4 says, "For with You is forgiveness," and is followed in Psalm 130:5 by, "I wait for the Lord."[123]

A Midrash told that when the Israelites asked Balaam when salvation would come, Balaam replied in the words of Numbers 24:17, "I see him (the Messiah), but not now; I behold him, but not near." God asked the Israelites whether they had lost their sense, for they should have known that Balaam would eventually descend to Gehinnom, and therefore did not wish God's salvation to come. God counseled the Israelites to be like Jacob, who said in Genesis 49:18, "I wait for Your salvation, O Lord." The Midrash taught that God counseled the Israelites to wait for salvation, which is at hand, as Isaiah 54:1 says, "For My salvation is near to come."[124]

.jpg)

A Midrash taught that the intent of Jacob's blessing of Joseph in Genesis 49:22, "Joseph is a fruitful vine (בֵּן פֹּרָת יוֹסֵף, bein porat Yoseif)," related to Joseph's interpretation of Pharaoh's dreams in Genesis 41. Noting the differences between the narrator's account of Pharaoh's dreams in Genesis 41:1–7 and Pharaoh's recounting of them to Joseph in Genesis 41:17–24, a Midrash taught that Pharaoh somewhat changed his account so as to test Joseph. As reported in Genesis 41:18, Pharaoh said, "Behold, there came up out of the river seven cows, fat-fleshed and well-favored (בְּרִיאוֹת בָּשָׂר, וִיפֹת תֹּאַר, beriot basar, vifot toar)." But Joseph replied that this was not what Pharaoh had seen, for they were (in the words of Genesis 41:2) "well-favored and fat-fleshed (יְפוֹת מַרְאֶה, וּבְרִיאֹת בָּשָׂר, yifot mareh, uvriot basar)." As reported in Genesis 41:19, Pharaoh said, "seven other cows came up after them, poor and very ill-favored (דַּלּוֹת וְרָעוֹת, dalot veraot) and lean-fleshed." But Joseph replied that this was not what Pharaoh had seen, for they were (in the words of Genesis 41:3) "ill favored and lean-fleshed (רָעוֹת מַרְאֶה, וְדַקּוֹת בָּשָׂר, raot mareh, vedakot basar)." As reported in Genesis 41:22, Pharaoh said that there were seven stalks, "full (מְלֵאֹת, meleiot) and good." But Joseph replied that this was not what Pharaoh had seen, for they were (in the words of Genesis 41:5) "healthy (בְּרִיאוֹת, beriot) and good." As reported in Genesis 41:23, Pharaoh said that there were then seven stalks, "withered, thin (צְנֻמוֹת דַּקּוֹת, tzenumot dakot)." But Joseph replied that this was not what Pharaoh had seen, for they were (in the words of Genesis 41:6) "thin and blasted with the east wind (דַּקּוֹת וּשְׁדוּפֹת קָדִים, dakot u-shedufot kadim)." Pharaoh began to wonder, and told Joseph that Joseph must have been behind Pharaoh when he dreamed, as Genesis 41:39 says, "Forasmuch as God has shown you all this." And this was the intent of Jacob's blessing of Joseph in Genesis 49:22, "Joseph is a fruitful vine (בֵּן פֹּרָת יוֹסֵף, bein porat Yoseif)," which the Midrash taught one should read as, "Joseph was among the cows (בֵּן הַפָּרוֹת יוֹסֵף, bein ha-parot Yoseif)." So Pharaoh then told Joseph, in the words of Genesis 41:40, "You shall be over my house."[125]

Rabbi Melai taught in the name of Rabbi Isaac of Magdala that from the day that Joseph departed from his brothers he abstained from wine, reading Genesis 49:26 to report, "The blessings of your father . . . shall be on the head of Joseph, and on the crown of the head of him who was a nazirite (since his departure) from his brethren." Rabbi Jose ben Haninah taught that the brothers also abstained from wine after they departed from him, for Genesis 43:34 reports, "And they drank, and were merry with him," implying that they broke their abstention "with him." But Rabbi Melai taught that the brothers did drink wine in moderation since their separation from Joseph, and only when reunited with Joseph did they drink to intoxication "with him."[126]

The Tosefta interpreted Genesis 49:27 to allude to produce yields of Bethel and Jericho. The Tosefta interpreted "Benjamin is a wolf that pounces" to mean that the land of Benjamin, the area of Bethel, jumped to produce crops early in the growing season. The Tosefta interpreted "in the morning he devours the prey" to mean that in Jericho produce was gone from the fields early in the seventh year. And the Tosefta interpreted "and in the evening he divides the spoil" to mean that in Bethel produce remained in the fields until late in the seventh year.[127]

Rav and Samuel differed with regard to the Machpelah Cave, to which Jacob referred in Genesis 49:29–32, and in which the Patriarchs and Matriarchs were buried. One said that the cave consisted of two rooms, one farther in than the other. And the other said that it consisted of a room and a second story above it. The Gemara granted that the meaning of “Machpelah” — “double” — was understandable according to the one who said the cave consisted of one room above the other, but questioned how the cave was “Machpelah” — “double” — according to the one who said it consisted of two rooms, one farther in than the other, as even ordinary houses have two rooms. The Gemara answered that it was called “Machpelah” in the sense that it was doubled with the Patriarchs and Matriarchs, who were buried there in pairs. The Gemara compared this to the homiletic interpretation of the alternative name for Hebron mentioned in Genesis 35:27: “Mamre of Kiryat Ha’Arba, which is Hebron.” Rabbi Isaac taught that the city was called “Kiryat Ha’Arba” — “the city of four” — because it was the city of the four couples buried there: Adam and Eve, Abraham and Sarah, Isaac and Rebecca, and Jacob and Leah.[128]

A Baraita taught that in all of Israel, there was no more rocky ground than that at Hebron, which is why the Patriarchs buried their dead there, as reported in Genesis 49:31. Even so, the Baraita interpreted the words "and Hebron was built seven years before Zoan in Egypt" in Numbers 13:22 to mean that Hebron was seven times as fertile as Zoan. The Baraita rejected the plain meaning of "built," reasoning that Ham would not build a house for his younger son Canaan (in whose land was Hebron) before he built one for his elder son Mizraim (in whose land was Zoan, and Genesis 10:6 lists (presumably in order of birth) "the sons of Ham: Cush, and Mizraim, and Put, and Canaan." The Baraita also taught that among all the nations, there was none more fertile than Egypt, for Genesis 13:10 says, "Like the garden of the Lord, like the land of Egypt." And there was no more fertile spot in Egypt than Zoan, where kings lived, for Isaiah 30:4 says of Pharaoh, "his princes are at Zoan." But rocky Hebron was still seven times as fertile as lush Zoan.[129]

Rabbi Isaac taught in the name of Rabbi Joḥanan that Jacob did not die. Genesis 49:33 reports only that "he gathered up his feet into the bed, and expired, and was gathered unto his people.") Rav Naḥman objected that he must have died, for he was bewailed (as Genesis 50:10 reports) and embalmed (as Genesis 50:2 reports) and buried (as Genesis 50:13 reports)! Rabbi Isaac replied that Rabbi Joḥanan derived his position that Jacob still lives from Jeremiah 30:10, which says, "Therefore fear not, O Jacob, My servant, says the Lord; neither be dismayed, O Israel, for, lo, I will save you from afar and your seed from the land of their captivity." Rabbi Isaac explained that since Jeremiah 30:10 likens Jacob to his descendants, then just as Jacob's descendants still live, so too must Jacob.[130]

.jpg)

Genesis Chapter 50

Rabbi Hiyya bar Abba taught in the name of Rabbi Joḥanan that when in Genesis 41:44 Pharaoh conferred power on Joseph, Pharaoh's astrologers questioned whether Pharaoh would set in power over them a slave whom his master bought for 20 pieces of silver. Pharaoh replied to them that he discerned royal characteristics in Joseph. Pharaoh's astrologers said to Pharaoh that in that case, Joseph must be able to speak the 70 languages of the world. That night, the angel Gabriel came to teach Joseph the 70 languages, but Joseph could not learn them. Thereupon Gabriel added a letter from God's Name to Joseph's name, and Joseph was able to learn the languages, as Psalm 81:6 reports, "He appointed it in Joseph for a testimony, when he went out over the land of Egypt, where I (Joseph) heard a language that I knew not." The next day, in whatever language Pharaoh spoke to Joseph, Joseph was able to reply to Pharaoh. But when Joseph spoke to Pharaoh in Hebrew, Pharaoh did not understand what he said. So Pharaoh asked Joseph to teach it to him. Joseph tried to teach Pharaoh Hebrew, but Pharaoh could not learn it. Pharaoh asked Joseph to swear that he would not reveal his failing, and Joseph swore. Later, in Genesis 50:5, when Joseph related to Pharaoh that Jacob had made Joseph swear to bury him in the Land of Israel, Pharaoh asked Joseph to seek to be released from the oath. But Joseph replied that in that case, he would also ask to be released from his oath to Pharaoh concerning Pharaoh's ignorance of languages. As a consequence, even though it was displeasing to Pharaoh, Pharaoh told Joseph in Genesis 50:6, "Go up and bury your father, as he made you swear."[131]

Rabbi taught that at a seaport that he visited, they called selling, כירה, "kirah". The Gemara explained that this helped to explain the expression in Genesis 50:5, אֲשֶׁר כָּרִיתִי, "asher kariti," often translated as "that I have dug for myself." In the light of Rabbi's report of the alternative usage, one can translate the phrase as "that I have bought for myself."[132]

The Mishnah cited Genesis 50:7–9 for the proposition that Providence treats a person measure for measure as that person treats others. And so because, as Genesis 50:7–9 relates, Joseph had the merit to bury his father and none of his brothers were greater than he was, so Joseph merited the greatest of Jews, Moses, to attend to his bones, as reported in Exodus 13:19.[133]

Rav Hisda deduced from the words "and he made a mourning for his father seven days" in Genesis 50:10 that Biblical "mourning" means seven days. And thus Rav Hisda deduced from the words "And his soul mourns for itself" in Job 14:22 that a person's soul mourns for that person for seven whole days after death.[134]

Rabbi Levi and Rabbi Isaac disagreed about how to interpret the words of Genesis 50:15, "And when Joseph's brethren saw that their father was dead, they said: ‘It may be that Joseph will hate us.'" Rabbi Levi taught that the brothers feared this because he did not invite them to dine with him. Rabbi Tanhuma observed that Joseph's motive was noble, for Joseph reasoned that formerly Jacob had placed Joseph above Judah, who was a king, and above Reuben, who was the firstborn, but after Jacob's death, it would not be right for Joseph to sit above them. The brothers, however, did not understand it that way, but worried that Joseph hated them. Rabbi Isaac said that the brothers feared because he had gone and looked into the pit into which they had thrown him.[135]

Rabban Simeon ben Gamliel read Genesis 50:15–17 to report that Joseph's brothers fabricated Jacob's request that Joseph forgive them in order to preserve peace in the family.[136]

Rabbi Jose bar Hanina noted that Joseph's brothers' used the word "please" (נָא, na) three times in Genesis 50:17 when they asked Joseph, "Forgive, I pray now . . . and now we pray." Rabbi Jose bar Hanina deduced from this example that one who asks forgiveness of a neighbor need do so no more than three times. And if the neighbor against whom one has sinned had died, one should bring ten persons to stand by the neighbor's grave and say: "I have sinned against the Lord, the God of Israel, and against this one, whom I have hurt."[137]

Rabbi Benjamin bar Japhet said in the name of Rabbi Elazar that Genesis 50:18 bore out the popular saying: "When the fox has its hour, bow down to it." But the Gemara questioned how Joseph was, like the fox relative to the lion, somehow inferior to his brothers. Rather, the Gemara applied the saying to Genesis 47:31, as discussed above.[138]

The Mekhilta of Rabbi Ishmael taught that the Israelites would later recall Joseph's question in Genesis 50:19, "am I in the place of God?" The Mekhilta taught that in their wanderings in the Wilderness, the Israelites carried Joseph's coffin alongside the Ark of the Covenant. The nations asked the Israelites what were the two chests, and the Israelites answered that one was the Ark of the Eternal, and the other was a coffin with a body in it. The nations then asked what was the significance of the coffin that the Israelites should carry it alongside the Ark. The Israelites answered that the one lying in the coffin had fulfilled that which was written on what lay in the Ark. On the tablets inside the Ark was written (in the words of Exodus 20:2), "I am the Lord your God," and of Joseph it is written (in the words of Genesis 50:19), "For, am I in the place of God?"[139]

The Mekhilta of Rabbi Ishmael read Joseph's statement to his brothers in Genesis 50:20, “And as for you, you meant evil against me; but God meant it for good,” as an application of the admonition of Leviticus 19:18, “You shall not take vengeance, nor bear any grudge."[140]

The Pesikta Rabbati taught that Joseph guarded himself against lechery and murder. That he guarded himself against lechery is demonstrated by the report of him in Genesis 39:8–9, “But he refused, and said to his master's wife: 'Behold, my master, having me, knows not what is in the house, and he has put all that he has into my hand; he is not greater in this house than I; neither has he kept back any thing from me but you, because you are his wife. How then can I do this great wickedness, and sin against God?” That he guarded himself against murder is demonstrated by his words in Genesis 50:20, “As for you, you meant evil against me; but God meant it for good.”[141]

.jpg)

Reading the words of Genesis 50:21, "he comforted them, and spoke kindly to them," Rabbi Benjamin bar Japhet said in the name of Rabbi Eleazar that this teaches that Joseph spoke to the Brothers words that greatly reassured them, asking that if ten lights were not able to put out one, how could one light put out ten. (If ten brothers could not harm one, then how could one harm ten?)[138]

Rabbi Jose deduced from Joseph's talk of providing in Genesis 50:21 that when Jacob died, the famine returned.[142]

Rabbi Eliezer taught that the five Hebrew letters of the Torah that alone among Hebrew letters have two separate shapes (depending whether they are in the middle or the end of a word) — צ פ נ מ כ (Kh, M, N, P, Z) — all relate to the mystery of the redemption. With the letter kaph (כ), God redeemed Abraham from Ur of the Chaldees, as in Genesis 12:1, God says, "Get you (לֶךְ-לְךָ, lekh lekha) out of your country, and from your kindred . . . to the land that I will show you." With the letter mem (מ), Isaac was redeemed from the land of the Philistines, as in Genesis 26:16, the Philistine king Abimelech told Isaac, "Go from us: for you are much mightier (מִמֶּנּוּ, מְאֹד, mimenu m'od) than we." With the letter nun (נ), Jacob was redeemed from the hand of Esau, as in Genesis 32:12, Jacob prayed, "Deliver me, I pray (הַצִּילֵנִי נָא, hazileini na), from the hand of my brother, from the hand of Esau." With the letter pe (פ), God redeemed Israel from Egypt, as in Exodus 3:16–17, God told Moses, "I have surely visited you, (פָּקֹד פָּקַדְתִּי, pakod pakadeti) and (seen) that which is done to you in Egypt, and I have said, I will bring you up out of the affliction of Egypt." With the letter tsade (צ), God will redeem Israel from the oppression of the kingdoms, and God will say to Israel, I have caused a branch to spring forth for you, as Zechariah 6:12 says, "Behold, the man whose name is the Branch (צֶמַח, zemach); and he shall grow up (יִצְמָח, yizmach) out of his place, and he shall build the temple of the Lord." These letters were delivered to Abraham. Abraham delivered them to Isaac, Isaac delivered them to Jacob, Jacob delivered the mystery of the Redemption to Joseph, and Joseph delivered the secret of the Redemption to his brothers, as in Genesis 50:24, Joseph told his brothers, "God will surely visit (פָּקֹד יִפְקֹד, pakod yifkod) you." Jacob's son Asher delivered the mystery of the Redemption to his daughter Serah. When Moses and Aaron came to the elders of Israel and performed signs in their sight, the elders told Serah. She told them that there is no reality in signs. The elders told her that Moses said, "God will surely visit (פָּקֹד יִפְקֹד, pakod yifkod) you" (as in Genesis 50:24). Serah told the elders that Moses was the one who would redeem Israel from Egypt, for she heard (in the words of Exodus 3:16), "I have surely visited (פָּקֹד פָּקַדְתִּי, pakod pakadeti) you." The people immediately believed in God and Moses, as Exodus 4:31 says, "And the people believed, and when they heard that the Lord had visited the children of Israel."[143]

Rav Judah asked in the name of Rav why Joseph referred to himself as "bones" during his lifetime (in Genesis 50:25), and explained that it was because he did not protect his father's honor when in Genesis 44:31 his brothers called Jacob "your servant our father" and Joseph failed to protest. And Rav Judah also said in the name of Rav (and others say that it was Rabbi Hama bar Hanina who said) that Joseph died before his brothers because he put on superior airs.[144]

A Baraita taught that the Serah the daughter of Asher mentioned in both Genesis 46:17 and Numbers 26:46 survived from the time Israel went down to Egypt to the time of the wandering in the Wilderness. The Gemara taught that Moses went to her to ask where the Egyptians had buried Joseph. She told him that the Egyptians had made a metal coffin for Joseph. The Egyptians set the coffin in the Nile so that its waters would be blessed. Moses went to the bank of the Nile and called to Joseph that the time had arrived for God to deliver the Israelites, and the oath that Joseph had imposed upon the children of Israel in Genesis 50:25 had reached its time of fulfillment. Moses called on Joseph to show himself, and Joseph's coffin immediately rose to the surface of the water.[145]

Noting that Numbers 27:1 reported the generations from Joseph to the daughters of Zelophehad, the Sifre taught that the daughters of Zelophehad loved the Land of Israel just as much as their ancestor Joseph did (when in Genesis 50:25 he extracted an oath from his brothers to return his body to the Land of Israel for burial).[146]

Rabbi Jose the Galilean taught that the "certain men who were unclean by the dead body of a man, so that they could not keep the Passover on that day" in Numbers 9:6 were those who bore Joseph's coffin, as implied in Genesis 50:25 and Exodus 13:19. The Gemara cited their doing so to support the law that one who is engaged on one religious duty is free from any other.[147]

Rav Judah taught that three things shorten a person's years: (1) to be given a Torah scroll from which to read and to refuse, (2) to be given a cup of benediction over which to say grace and to refuse, and (3) to assume airs of authority. To support the proposition that assuming airs of authority shortens one's life, the Gemara cited the teaching of Rabbi Hama bar Hanina that Joseph died (as Genesis 50:26 reports, at the age of 110) before his brothers because he assumed airs of authority (when in Genesis 43:28 and 44:24–32 he repeatedly allowed his brothers to describe his father Jacob as "your servant").[148]

Rabbi Nathan taught that the Egyptians buried Joseph in the capital of Egypt in the mausoleum of the kings, as Genesis 50:26 reports, "they embalmed him, and he was put in a coffin in Egypt." Later, Moses stood among the coffins and cried out to Joseph, crying that the oath to redeem God's children that God swore to Abraham had reached its fulfillment. Immediately, Joseph's coffin began to move, and Moses took it and went on his way.[149]

In modern interpretation

The parashah is discussed in these modern sources:

Genesis chapters 37–50

Donald A. Seybold of Purdue University schematized the Joseph narrative in the chart below, finding analogous relationships in each of Joseph's households.[150]

| At Home | Potiphar's House | Prison | Pharaoh's Court | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genesis 37:1–36 | Genesis 37:3–33 | Genesis 39:1–20 | Genesis 39:12–41:14 | Genesis 39:20–41:14 | Genesis 41:14–50:26 | Genesis 41:1–50:26 | |

| Ruler | Jacob | Potiphar | Prison-keeper | Pharaoh | |||

| Deputy | Joseph | Joseph | Joseph | Joseph | |||

| Other "Subjects" | Brothers | Servants | Prisoners | Citizens | |||

| Symbols of Position and Transition | Long Sleeved Robe | Cloak | Shaved and Changed Clothes | ||||

| Symbols of Ambiguity and Paradox | Pit | Prison | Egypt |

Professor Ephraim Speiser of the University of Pennsylvania in the mid 20th century argued that in spite of its surface unity, the Joseph story, on closer scrutiny, yields two parallel strands similar in general outline, yet markedly different in detail. The Jahwist’s version employed the Tetragrammaton and the name “Israel.” In that version, Judah persuaded his brothers not to kill Joseph but sell him instead to Ishmaelites, who disposed of him in Egypt to an unnamed official. Joseph's new master promoted him to the position of chief retainer. When the brothers were on their way home from their first mission to Egypt with grain, they opened their bags at a night stop and were shocked to find the payment for their purchases. Judah prevailed on his father to let Benjamin accompany them on a second journey to Egypt. Judah finally convinced Joseph that the brothers had really reformed. Joseph invited Israel to settle with his family in Goshen. The Elohist’s parallel account, in contrast, consistently used the names “Elohim” and “Jacob.” Reuben — not Judah — saved Joseph from his brothers; Joseph was left in an empty cistern, where he was picked up, unbeknown to the brothers, by Midianites; they — not the Ishmaelites — sold Joseph as a slave to an Egyptian named Potiphar. In that lowly position, Joseph served — not supervised — the other prisoners. The brothers opened their sacks — not bags — at home in Canaan — not at an encampment along the way. Reuben — not Judah — gave Jacob — not Israel — his personal guarantee of Benjamin's safe return. Pharaoh — not Joseph — invited Jacob and his family to settle in Egypt — not just Goshen. Speiser concluded that the Joseph story can thus be traced back to two once separate, though now intertwined, accounts.[151]

Professor John Kselman, formerly of the Weston Jesuit School of Theology, reported that more recent scholarship finds in the Joseph story a background in the Solomonic era, as Solomon's marriage to a daughter of the pharaoh (reported in 1 Kings 9:16 and 11:1) indicated an era of amicable political and commercial relations between Egypt and Israel that would explain the positive attitude of the Joseph narrative to Egypt.[152]