Udawattakele Forest Reserve

Udawattakele Forest Reserve, often spelled as Udawatta Kele, is a historic forest reserve on a hill-ridge in the city of Kandy. It is 104 hectares (257 acres) large. During the days of the Kandyan kingdom, Udawattakele was known as "Uda Wasala Watta" in Sinhalese meaning "the garden above the royal palace". The sanctuary is famous for its extensive avifauna. The reserve also contains a great variety of plant species, especially lianas, shrubs and small trees. There are several giant lianas. Many of small and medium size mammals that inhabit Sri Lanka can be seen here. Several kinds of snakes and other reptiles might be seen. Udawattakele was designated as a forest reserve in 1856, and it became a sanctuary in 1938.[1][2][3]

| Udawattakele Forest Reserve | |

|---|---|

IUCN category IV (habitat/species management area) | |

Udawattakele seen in the background of Temple of the Tooth | |

Location of Udawattakele Forest Reserve | |

| Location | Central province, Sri Lanka |

| Nearest city | in the city limits of Kandy |

| Coordinates | 7°17′58″N 80°38′20″E |

| Area | 103 hectares (0.40 sq mi) |

| Established | 1856 (Forest reserve) 1938 (Sanctuary) |

| Governing body | Department of Wildlife Conservation |

The Sri Lanka Forest Department has two offices in the reserve, one of which (at the southeastern entrance) has a nature education centre with a display of pictures, posters, stuffed animals, etc. Being easily accessible and containing a variety of flora and fauna the forest has a great educational and recreational value. Groups of school children and students regularly visit the forest and the education centre. The forest is also popular with foreign tourists, especially bird watchers. Scientific nature research has been carried out in the forest by researchers. The forest is of religious importance as there are three Buddhist meditation hermitages and three rock shelter dwellings for Buddhist monk hermits.[4][5]

History

It has been recorded that the brahmin called Senkanda, from whose name the city's original name Senkandagalapura derives, lived in a cave in this forest.[6] The rock-shelter or cave now known as the Senkandagala-lena is on the slope above the temple of the tooth and can be visited. The Senkandagala-lena collapsed in a landslide in 2012. The legend says the brahmin brought a sapling of Jaya Sri Maha Bodhi here and planted it in the present site of Natha Devala.[7][8] It was used as a pleasure garden by the Kandyan kings. The forest was reserved for the Royal family, and the pond in the forest was used for bathing.[3] The public was restricted from accessing the forest hence the name Thahanci kele (Sinhalese for Forbidden forest).[9][10]

During the colonial era some of the land near the Temple of the Tooth was used to build the Kandy garrison cemetery.[11][12] In 1834 governor Horton built a path, Lady Horton's drive, in the forest in remembrance of his wife. Henry W. Cave mentions the trail is about three miles long.[13] Lady McCarthy's drive, Lady Torrington's road, Lady Gordon's road, Lady Anderson's road, Gregory path, Russell path, and Byrde lane are the other named walks in the forest. Some have gone in disuse long ago and are overgrown by the forest.[14]

On two hilltops in the southeastern side of the forest the overgrown remains of a garrison post from the first British occupation of the Kandyan Kingdom [15] can be found. It is located in the jungle on the elevated areas to the east and west of the nature education centre. Ramparts and moats can still be seen in the jungle. On 24 June 1803 the forces of King Sri Wickrama Rajasingha attacked this post where the British troops were stationed in Kandy and made the garrison (mostly consisting of Malay and 'Gun Lascar' or Sepoy mercenaries) prisoners. Most of the British were later massacred.[16]

Features

Udawattakele is located on a hill ridge stretching between the Temple of the Tooth and the Uplands-Aruppola housing schemes. The highest point of the ridge (7°17'55.41"N, 80°38'40.04"O) is 635 meters above sea level and 115 meters above the nearby Kandy Lake.

The sanctuary contains three Buddhist forest monasteries, i.e., Forest Hermitage, Senanayakaramaya and Tapovanaya, and three cave dwellings for Buddhist monks, i.e., Cittavisuddhi-lena, Maitri-lena and Senkadandagala-lena. The sanctuary acts as a catchment area for the supply of water to the city of Kandy.[17][18][19]

Visiting

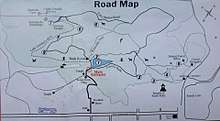

The visitors' entrance is on the western side of the forest, about 15–20 minutes walking from the Temple of the Tooth. From the Temple of the Tooth, go north along the D.S. Senanayaka Veediya road and after half a kilometer turn right at the post office near the Kandy Municipality, and follow the road up the hill. The entrance is on the right side of the Tapovanaya Monastery.

There is parking space for cars and vans near the entrance and a refreshment stall. The entrance fee for Sri Lankan visitors is Rs. 30,-; the fee for foreign visitors is Rs. 570,-. Sri Lankan visitors have to register and leave their identity card at the entrance. Amorous unmarried couples are not allowed to enter the forest. The shady lovers' walk, which runs along the banks of the royal pond, is the most popular walk.[12]

During rainy weather there are leeches lurking along paths that will attempt to suck blood from the feet and legs of unwary visitors. Mosquito repellent or herbal balms such as Siddhalepa will protect against them.

Flora

The vegetation of the park comprises dense forest, mostly abandoned plantations and secondary formations.[20] According to Hitanayake, perhaps basing himself on Karunaratne (1986, Appendix XIII) 460 plant species were growing in the forest, 135 tree and shrub species and 11 are lianas. These include 9 endemic species.[21]

In 2013, a survey identified 58 indigenous tree species (7 endemic), 61 indigenous shrub and small tree species (7 endemic), 31 indigenous herbs (3 endemic) of which 12 are orchids, and 57 indigenous lianas, creepers and vines (4 endemic).[22] The forest features an emergent layer, a canopy and an understory.[3] Because of the dense two upper layers, understory is not present everywhere, especially in areas with the invasive balsam of Peru tree, (Myroxylon balsamum), Mahogany trees, (Swietenia macrophylla) and Devil's Ivy (see Threats section below).

A great variety of plant species are found in the relatively unspoilt northern and eastern sides of the forest. Some common indigenous tree and shrub species are Acronychia pedunculata (Sinhalese: "ankenda"), Artocarpus nobilis ("wal del"), Artocarpus heterophyllus ("kos"), Caryota urens ("kitul"), Aglaia elaeagnoidea ("puwanga"), Bombax ceiba ("katu imbul"), Canarium zeylanicum, Cinnamomum verum ("kurundu", cinnamon), Ficus virens, Filicium decipiens ("pihimbiya"), Aphananthe cuspidata ("wal-munamal"), Goniothalamus gardneri, Haldina cordifolia, Hunteria zeylanica, Mallotus tetracoccus, Mesua ferrea ("na", iron-wood), Michelia champaca ("sapu"), Mangifera zeylanica ("atamba"), Neoclitsea cassia ("dawul kurundu”, wild cinnamon), Glycosmis pentaphylla (orangeberry, doda-pana), Litsea quinqueflora, Micromelum minitum ("wal karapuncha"), Pavetta blanda, Psychotria nigra, Vitex pinnata ("milla") and Walsura gardneri.[23][24]

There are many climber and liana species growing in the Udawattakele forest, most notable is the giant Sea Bean climber Entada rheedii ("Pus Wel"). Some other species are Anamirta cocculus ("Tittawel”), Diploclisia glaucescens, Hiptage bengalensis, Hypserpa nitida ("Niriwel"), Morinda umbellata ("Kiri-wel"), and Paramignya monophylla. The Udawattakele contains many full-grown rattan palms, ''Calamus'' (palm), of which there are two species. Some of the climbing palms here are over 25 meters long, growing up and over trees. Elsewhere in Sri Lanka rattan palms are often cut down when young for making rattan.[25]

Orchid species, mostly epiphytic, include Cymbidium bicolor, Luisa teretifolia, Polystachya concreta, Thrixspermum pulchellum, Tropidia curculigoides and Vanda testacea.[26]

The sanctuary is home to many species of non-flowering plants, pteridophytes, such as the many kinds of ferns growing on steep banks along the shady road on the eastern side of the hill ridge.[27] The invasive glossy maidenhair fern (Adiantum pulverulentum) is said to crowd away native fern species, some of which are rare and not recorded elsewhere in Sri Lanka.[28]

About half of the forest, mostly on the southwestern side, is heavily invaded by exotic tree and creeper species. In these areas very little native vegetation and fauna is able to survive; see the Threats section below. In total 16 exotic tree species grow in the forest (7 of which are invasive), as well as 6 exotic shrub species (one, Coffea, is invasive), 6 exotic liana and creeper species (of which three are invasive), and 6 exotic herbs (one of which is invasive).[29]

Fauna

Udawattakele is a famous birdwatching site. About 80 bird species have been recorded in the sanctuary.[20] The endemic bird species are Layard's parakeet, yellow-fronted barbet, brown-capped babbler and Sri Lanka hanging parrot . The rare three-toed kingfisher Ceyx erythacus has been observed occasionally at the pond. Common hill myna, golden-fronted leafbird, blue-winged leafbird, spotted dove, emerald dove, Tickell's blue flycatcher, white-rumped shama, crimson-fronted barbet, brown-headed barbet crested serpent eagle, and brown fish owl are regularly seen and heard in the forest.[30][31][32]

Despite the forest reserve being completely surrounded by Kandy and its suburbs, there are many kinds of mammals, most of which are nocturnal. Endemic mammals that live in the sanctuary are the pale-fronted toque macaque (Macaca sinica aurifrons), golden palm civet, mouse deer (Moschiola meminna), slender loris, and the dusky palm squirrel. Other mammals are the Indian muntjac, Indian boar, porcupine (Hysterix indica), Asian palm civet, small Indian civet, ruddy mongoose, Indian giant flying squirrel, greater bandicoot rat, Indian pangolin, greater false vampire bat, and Indian flying-fox.[33]

Several kinds of reptiles and amphibians, including endemic species, inhabit the forest. There are snakes such as the common hump-nosed pit viper (Hypnale hypnale), green vine snake (Ahaetulla nasuta), green pit viper (Trimeresurus trigonocephalus), banded kukri (Oligodon arnensis), Boie's rough-sided snake (Aspidura brachyorrhos) Sri Lanka cat snake (Boiga ceylonensis), Oriental ratsnake (Ptyas mucosus) and spectacled cobra (Naja naja). Lizards that can be seen include the green forest lizard (Calotes calotes), Sri Lanka kangaroo-lizard (Otocryptis wiegmanni) and the whistling lizard (Calotes liolepis). Many species of skinks, geckos, frogs and toads also inhabit the forest.[34]

Some Sri Lanka wet zone butterflies are present.[35][3] Other invertebrate include giant forest scorpions Heterometrus spp., spiders such as the poisonous Sri Lankan ornamental tarantula (Poecilotheria fasciata), fireflies, beetles, jewel bugs, bees and wasps. At least nine species of endemic land snails such as the large Acavus superbus live in the forest.[36]

Threats

Udawattakele Forest Reserve has suffered from encroachment by squatters and land grabbing by surrounding land owners[10] in the past. But the forest ecosystem is now mainly threatened by highly invasive, introduced exotic plant species that increasingly crowd native plant and tree species and the animals and insects that live on them. The invasive tree and creeper species have no natural enemies such as diseases or insects and animals that feed on them and therefore grow and multiply much more rapidly than in their native habitats. About half of the forest is already heavily or completely invaded and smothered by exotic, invasive trees and creepers.[37]

Introduced species pose the biggest threat to the natural biodiversity of the Udawattakele forest:

- The highly invasive Peru balsam tree Myroxylon balsamum from South America is the first. Dense stands of thousands of young trees can be seen along the roads in the eastern and northern side of the forest.

- The pothos or devil's ivy, Epipremnum aureum, creeper from the Solomon Islands is the second major threat. In the northwestern and western part of the reserve, around the royal pond and near the presidential palace and Temple of the Tooth, the creepers completely cover several hectares of the forest floor. They also climb high up tree trunks, and their large leaves block the light for other species underneath. The creepers are gradually spreading further to the east and south. Some years ago they were planted on road banks elsewhere in the forest.

- Mahogany, Swietenia macrophylla, a timber tree from South America, is quite invasive and disrupts the forest's diverse ecology.

- Coffee shrubs (Coffea robusta or Coffea arabica) are invasive in parts of the forest, as they are in the nearby Gannoruwa Forest Reserve at Peradeniya.

- The glow vine, Saritaea magnifica, from Brazil is another invasive species, and covers several trees near the royal pond and near the Maitri cave.

- In some areas Aglaonema commutatum, a Philippine evergreen, covers the forest floor and road banks.[38][39]

Severely degraded forest areas are between the Temple of the Tooth, the forest department office at the western entrance, and the slopes northeast of the royal pond. A few patches of unspoiled forest, with mostly native species of trees and shrubs, remain on the northern and eastern sides of the forest. There is a patch of native forest, near the forest department office at the southeastern entrance.[40]

Despite the forest being of great educational, scientific, ecological, historical and cultural value, the Forest Department has no management plan to maintain the biodiversity and remove the invasive species to restore and protect the native vegetation. Necessary control measures would be the uprooting of seedlings, collecting and destroying seeds, and removal of mother trees and creepers.[21][41]

Pictures of the Udawattakele Forest

Forest

Forest Forest

Forest Forest

Forest Forest

Forest Introduction at the entrance

Introduction at the entrance Cittavisuddhi Lena

Cittavisuddhi Lena Maitri Lena

Maitri Lena Barking deer at forest edge

Barking deer at forest edge Female pale-fronted toque macaques

Female pale-fronted toque macaques Giant lianas on hill ridge

Giant lianas on hill ridge Forest scenery

Forest scenery Royal Pond

Royal Pond Large tree

Large tree Forest scenery

Forest scenery Garrison Cemetery

Garrison Cemetery Forest, southeast

Forest, southeast Lianas

Lianas Balsam of Peru tree infestation

Balsam of Peru tree infestation Mahogany tree infestation

Mahogany tree infestation

See also

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Udawatta Kele Sanctuary. |

- Bhikkhu Nyanatusita & Rajith Dissanayake, Udawattakele: “A Sanctuary Destroyed From Within”, Loris, Journal of the Wildlife and Nature Protection Society of Sri Lanka, Vol. 26, Issue 5 & 6, 2013, p. 38.View:

- Karunaratna N. Udavattakälē: The Forbidden Forest of the Kings of Kandy, Colombo: Department of National Archives; 1986. pp. 1–19.View:

- Senarathna, P.M. (2005). Sri Lankawe Wananthara (in Sinhala) (1st ed.). Sarasavi publishers. pp. 151–152. ISBN 955-573-401-1.

- Bhikkhu Nyanatusita & Rajith Dissanayake, Udawattakele: “A Sanctuary Destroyed From Within”, Loris, Journal of the Wildlife and Nature Protection Society of Sri Lanka, Vol. 26, Issue 5 & 6, 2013, p. 38. View:

- Karunaratna N. Udavattakälē: The Forbidden Forest of the Kings of Kandy, Colombo: Department of National Archives; 1986. pp. 1–19.

- Seneviratna, Anuradha (1989). Kanda Udarata Mahanuwara (in Sinhala). Colombo: Ministry of Cultural affairs (Sri Lanka). pp. 12–15.

- Karunaratna N. Udavattakäle: The Forbidden Forest of the Kings of Kandy, Colombo: Department of National Archives; 1986. pp. 1–3.View:

- Abhayawardena, H.A.P. (2004). Kandurata Praveniya (in Sinhala) (1st ed.). Colombo: Central Bank of Sri Lanka. pp. 60–62. ISBN 9789555750929.

- Karunaratna N. Udavattakäle: The Forbidden Forest of the Kings of Kandy, Colombo: Department of National Archives; 1986. pp. 1–19.View:

- de Silva, Haris (2009-06-15). "Illegal clearing of Udawatta Kele" (PDF). The Island. Upali Newspapers Limited. Retrieved 2009-07-07.

- Karunaratna N. Udavattakäle: The Forbidden Forest of the Kings of Kandy, Colombo: Department of National Archives; 1986. pp. 57.

- Pradeepa, Ganga (2009-03-20). "Udawattakele". Daily News. The Associated Newspapers of Ceylon Ltd. Retrieved 2009-07-07.

- Cave, Henry W. (2003). Ceylon along the Rail Track (2nd Visidunu ed.). Visidunu publishers. p. 105. ISBN 955-9170-46-5.

- Karunaratna N. Udavattakäle: The Forbidden Forest of the Kings of Kandy, Colombo: Department of National Archives; 1986. pp. 71–73.View:

- Karunaratna N. Udavattakäle: The Forbidden Forest of the Kings of Kandy, Colombo: Department of National Archives; 1986. pp.72–74.View:

- Marshall. Henry. Ceylon: A General Description of the Island and Its Inhabitants, W.H. Allen, Sri Lanka, 1846: 96.

- Bhikkhu Nyanatusita & Rajith Dissanayake, Udawattakele: “A Sanctuary Destroyed From Within”, Loris, Journal of the Wildlife and Nature Protection Society of Sri Lanka, Vol. 26, Issue 5 & 6, 2013, p. 38. View:

- Karunaratna N. Udavattakäle: The Forbidden Forest of the Kings of Kandy, Colombo: Department of National Archives; 1986. pp. 1–19.View:

- Sakalasooriya, Indika (August 5, 2007). "Sanctuary of the kings" (PDF). nation.lk. Retrieved 2009-07-07.

- Green, Michael J. B. (1990). IUCN directory of South Asian protected areas. IUCN. pp. 263–265. ISBN 978-2-8317-0030-4.

- Wedathanthri, H.P.; Hitinayake, H.M.G.S.B. "Invasive behavior of Myroxylon balsamum at Udawattakele forest reserve". tripod.com. University of Sri Jayewardenepura. Retrieved 2009-07-07.

- Bhikkhu Nyanatusita & Rajith Dissanayake, Udawattakele: “A Sanctuary Destroyed From Within”, Loris, Journal of the Wildlife and Nature Protection Society of Sri Lanka, Vol. 26, Issue 5 & 6, 2013, p. 40 View:

- Bhikkhu Nyanatusita & Rajith Dissanayake, Udawattakele: “A Sanctuary Destroyed From Within”, Loris, Journal of the Wildlife and Nature Protection Society of Sri Lanka, Vol. 26, Issue 5 & 6, 2013, pp. 39–40 View:

- Karunaratna N. Udavattakäle: The Forbidden Forest of the Kings of Kandy, Colombo: Department of National Archives; 1986. Ch. XIV, Appendix 13.View:

- Bhikkhu Nyanatusita & Rajith Dissanayake, Udawattakele: “A Sanctuary Destroyed From Within”, Loris, Journal of the Wildlife and Nature Protection Society of Sri Lanka, Vol. 26, Issue 5 & 6, 2013, pp. 39–40 View:

- Bhikkhu Nyanatusita & Rajith Dissanayake, Udawattakele: “A Sanctuary Destroyed From Within”, Loris, Journal of the Wildlife and Nature Protection Society of Sri Lanka, Vol. 26, Issue 5 & 6, 2013, pp. 39–40 View:

- Karunarathna, Dewwanthi (March 5, 2008). "Pteridophyte Flora of Udawattakele forest: the past, present and future". environmentlanka.com. Retrieved 2009-07-07.

- Bhikkhu Nyanatusita & Rajith Dissanayake, Udawattakele: “A Sanctuary Destroyed From Within”, Loris, Journal of the Wildlife and Nature Protection Society of Sri Lanka, Vol. 26, Issue 5 & 6, 2013, pp. 39–40. View:

- Bhikkhu Nyanatusita & Rajith Dissanayake, Udawattakele: “A Sanctuary Destroyed From Within”, Loris, Journal of the Wildlife and Nature Protection Society of Sri Lanka, Vol. 26, Issue 5 & 6, 2013, pp. 39–40. View:

- Karunaratna N. Udavattakälē: The Forbidden forest of the kings of Kandy, Colombo: Department of National Archives; 1986. pp. 141–148.View:

- "Udawattakele Sanctuary, Kandy, Central Province". info.lk. Retrieved 2009-07-07.

- Bhikkhu Nyanatusita & Rajith Dissanayake, Udawattakele: “A Sanctuary Destroyed From Within”, Loris, Journal of the Wildlife and Nature Protection Society of Sri Lanka, Vol. 26, Issue 5 & 6, 2013, pp. 39. View:

- Bhikkhu Nyanatusita & Rajith Dissanayake, Udawattakele: “A Sanctuary Destroyed From Within”, Loris, Journal of the Wildlife and Nature Protection Society of Sri Lanka, Vol. 26, Issue 5 & 6, 2013, pp. 39–40. View:

- Bhikkhu Nyanatusita & Rajith Dissanayake, Udawattakele: “A Sanctuary Destroyed From Within”, Loris, Journal of the Wildlife and Nature Protection Society of Sri Lanka, Vol. 26, Issue 5 & 6, 2013, pp. 39–40. View:

- Karunaratna N. Udavattakälē: The Forbidden Forest of the Kings of Kandy, Colombo: Department of National Archives; 1986. pp. 149–152.View:

- Bhikkhu Nyanatusita & Rajith Dissanayake, Udawattakele: “A Sanctuary Destroyed From Within”, Loris, Journal of the Wildlife and Nature Protection Society of Sri Lanka, Vol. 26, Issue 5 & 6, 2013, pp. 39. View:

- Bhikkhu Nyanatusita & Rajith Dissanayake, Udawattakele: “A Sanctuary Destroyed From Within”, Loris, Journal of the Wildlife and Nature Protection Society of Sri Lanka, Vol. 26, Issue 5 & 6, 2013, pp. 40–46. View:

- Bhikkhu Nyanatusita & Rajith Dissanayake, Udawattakele: “A Sanctuary Destroyed From Within”, Loris, Journal of the Wildlife and Nature Protection Society of Sri Lanka, Vol. 26, Issue 5 & 6, 2013, pp. 40–46. View:

- Hitinayake H.M.G.S.B., Wedathanthri H.P. “Invasive behaviour of Myroxylon balsamum of Udawattekelle Forest Reserve.” Proceedings of the forestry and environment symposium: Department of Forestry and Environmental Science, University of Sri Jayewardenepura; 1999. http://journals.sjp.ac.lk/index.php/fesympo/article/download/1559/729 (Accessed: 17/11/2014).

- Bhikkhu Nyanatusita & Rajith Dissanayake, Udawattakele: “A Sanctuary Destroyed From Within”, Loris, Journal of the Wildlife and Nature Protection Society of Sri Lanka, Vol. 26, Issue 5 & 6, 2013, p. 44. View:.

- Bhikkhu Nyanatusita & Rajith Dissanayake, Udawattakele: “A Sanctuary Destroyed From Within”, Loris, Journal of the Wildlife and Nature Protection Society of Sri Lanka, Vol. 26, Issue 5 & 6, 2013, p. 44. View: