Ordination hall

The ordination hall is a Buddhist building specifically consecrated and designated for the performance of the Buddhist ordination ritual (upasampada) and other ritual ceremonies, such as the recitation of the Patimokkha.[1][2] The ordination hall is located within a boundary (sīmā) that defines "the space within which all members of a single local community have to assemble as a complete Sangha (samagga sangha) at a place appointed for ecclesiastical acts (kamma)." [3] The constitution of the sīmā is regulated and defined by the Vinaya and its commentaries and sub-commentaries.[3]

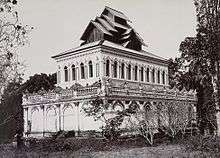

Burmese ordination halls

In Burmese, ordination halls are called thein (Burmese: သိမ်), derived from the Pali term sīmā, which means "boundary." The thein is a common feature of Burmese monasteries (kyaung), although the thein may be not necessarily be located on the monastery compound itself.[2] Shan ordination halls, called sim (သိမ်ႇ), are exclusively used for events limited to the monkhood.[4][5]

The central importance of the ordination hall in the pre-colonial era is exemplified by the inclusion of an ordination hall, the Maha Pahtan Haw Shwe Ordination Hall (မဟာပဋ္ဌာန်းဟောရွှေသိမ်တော်ကြီး), as one of seven requisite edifices (နန်းတည်သတ္တဌာန) in the founding of Mandalay as a Burmese royal capital.[6][7]

Thai ordination halls

In Thailand, ordination halls are called ubosot (Thai: อุโบสถ, pronounced [ʔù.boː.sòt]) or bot (โบสถ์, [bòːt]), derived from the Pali term uposathāgāra, meaning a hall used for rituals on uposatha ("Buddhist sabbath") days.[8] The ubosot is the focal point of Central Thai temples, whereas the focal point of Northern Thai temples is the stupa.[4] In Northeastern Thailand (Isan), ordination halls are known as sim (สิม), as they are in Laos (Lao: ສິມ). The ubosot, as the wat's principal building, is also used for communal services.[2][4]

In the Thai tradition, the boundary of the ubosot is marked by eight boundary stones known as bai sema, which denote the sīmā. The oldest bai sema date to the Dvaravati period.[3] The sema stones stand above and mark the luk nimit (ลูกนิมิต), stone spheres buried at the cardinal points of the compass delineating the sacred area. A ninth stone sphere, usually bigger, is buried below the main Buddha image of the ubosot. The entrance sides of most ubosot face east. While wihan buildings also similarly house Buddha images, they differ from ubosot in that wihan are not marked by sema stones. Across from the entrance door at the end of the interior is the ubosot's largest Buddha statue which is usually depicted in either the meditation attitude or the Maravijaya attitude.

See also

References

- Murphy, Stephen A. (2014). "Sema Stones in Lower Myanmar and Northeast Thailand: A Comparison". Before Siam: Essays in Art and Archaeology. River Books & The Siam Society.

- O'Connor, Richard A. (2009). "Place, Power and People: Southeast Asia's Temple Tradition". Arts Asiatiques. 64 (1): 116–123. doi:10.3406/arasi.2009.1692.

- Kieffer-Pülz, Petra (1997). "Rules for the sīmā Regulation in the Vinaya and its Commentaries and their Application in Thailand". Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies. 20 (2): 141–153. ISSN 0193-600X.

- Tannenbaum, Nicola (1990). "THE HEART OF THE VILLAGE: CONSTITUENT STRUCTURES OF SHAN COMMUNITIES". Crossroads: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. 5 (1): 23–41. JSTOR 40860287.

- Sao Tern Moeng (1995). "Shan-English Dictionary". Dunwoody Press.

- ဇင်ဦး. "မန္တလေးမြို့တည်နန်းတည် သတ္တ (၇) ဌာန ပြုပြင်မွမ်းမံမှု ၉၅ ရာခိုင်နှုန်းပြီးစီး". Ministry of Information (in Burmese). Retrieved 2020-05-17.

- The seven requisite edifices in founding Mandalay include the city walls (နန်းမြို့ရိုး), the city moat (ကျုံးတော်), Atumashi Monastery (အတုမရှိကျောင်းတော်ကြီး), the Pitakataik (Mandalay) (ပိဋကတ်တိုက်တော်ကြီး), the Thudhamma Zayat (သုဓမ္မာဇရပ်တော်ကြီး), Kuthodaw Pagoda (ကုသိုလ်တော်ဘုရား), and the Maha Pahtan Ordination Hall (မဟာပဋ္ဌာန်းဟောရွှေသိမ်တော်ကြီး).

- Architecture of Thailand. A Guide to Traditional and Contemporary Forms. Nithi Sthapitanonda; Brian Mertens.

Further reading

- Karl Döhring: Buddhist Temples Of Thailand. Berlin 1920, reprint by White Lotus Co. Ltd., Bangkok 2000, ISBN 974-7534-40-1

- K.I. Matics: Introduction To The Thai Temple. White Lotus, Bangkok 1992, ISBN 974-8495-42-6

- No Na Paknam: The Buddhist Boundary Markers of Thailand. Muang Boran Press, Bangkok 1981 (no ISBN)

- Carol Stratton: What's What in a Wat, Thai Buddhist Temples. Silkworm Books, Chiang Mai 2010, ISBN 978-974-9511-99-2