USS Tennessee (BB-43)

USS Tennessee (BB-43) was the lead ship of the Tennessee class of dreadnought battleships built for the United States Navy in the 1910s. The Tennessee class was part of the standard series of twelve battleships built in the 1910s and 1920s, and were developments of the preceding New Mexico class. They were armed with a battery of twelve 14-inch (360 mm) guns in four three-gun turrets. Tennessee served in the Pacific Fleet for duration of her peacetime career. She spent the 1920s and 1930s participating in routine fleet training exercises, including the annual Fleet Problems, and cruises around the Americas and further abroad, such as a goodwill visit to Australia and New Zealand in 1925.

USS Tennessee (BB-43), underway on 12 May 1943. | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Tennessee |

| Namesake: | State of Tennessee |

| Ordered: | 28 December 1915 |

| Builder: | New York Naval Shipyard |

| Laid down: | 14 May 1917 |

| Launched: | 30 April 1919 |

| Commissioned: | 3 June 1920 |

| Decommissioned: | 14 February 1947 |

| Stricken: | 1 March 1959 |

| Identification: | Hull symbol:BB-43 |

| Fate: | Broken up, 1959 |

| General characteristics (as built) | |

| Class and type: | Tennessee-class battleship |

| Displacement: | |

| Length: |

|

| Beam: | 97 ft 5 in (29.69 m) |

| Draft: | 30 ft 2 in (9.19 m) |

| Installed power: |

|

| Propulsion: |

|

| Speed: | 21 knots (39 km/h; 24 mph) |

| Range: | 8,000 nmi (15,000 km; 9,200 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Complement: |

|

| Armament: |

|

| Armor: |

|

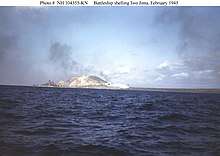

Tennessee was moored in Battleship Row when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941, which brought the United States into World War II. She was not seriously damaged, and after being repaired she operated off the West Coast of the US in 1942. In 1943, Tennessee and many of the older battleships were thoroughly rebuilt to prepare them for operations in the Pacific War and in June–August, she took part in the Aleutian Islands Campaign, providing gunfire support to troops fighting to retake the islands. The Gilbert and Marshall Islands campaign followed from November 1943 to February 1944, including the Battles of Tarawa, Kwajalein, and Eniwetok. In March, she raided Kavieng to distract Japanese forces during the landing on Emirau, and from June through September, she fought in the Mariana and Palau Islands campaign, bombarding Japanese forces during the Battles of Saipan, Guam, Tinian, and Anguar.

The Philippines campaign followed in September, during which the ship operated as part of the bombardment group at the Battle of Leyte. The Japanese launched a major naval counterattack that resulted in the Battle of Leyte Gulf, a series of four naval engagements. During the Battle of Surigao Strait, Tennessee formed part of the US line of battle that defeated a Japanese squadron; this was the last battleship engagement in history. Tennessee shelled Japanese forces during the Battle of Iwo Jima in February 1945 and the Battle of Okinawa from March to June. During the latter action, she was hit by a kamikaze but was not seriously damaged. In the final months of the war, she operated primarily in the East China Sea, and after Japan's surrender in August, she participated in the occupation of Japan before returning to the US late in the year. In the postwar draw down of naval forces, Tennessee was placed in the reserve fleet in 1946 and retained, out of service, until 1959, when the Navy decided to discard her. The ship was sold to Bethlehem Steel in July and broken up for scrap.

Design

The two Tennessee-class battleships were authorized on 3 March 1915, and they were in most respects repeats of the earlier New Mexico-class battleships, the primary differences being enlarged bridges, greater elevation for the main battery turrets, and relocation of the secondary battery to the upper deck.[1]

Tennessee was 624 feet (190 m) long overall and had a beam of 97 ft 5 in (29.69 m) and a draft of 30 ft 2 in (9.19 m). She displaced 32,300 long tons (32,818 t) as designed and up to 33,190 long tons (33,723 t) at full combat load. The ship was powered by four-shaft General Electric turbo-electric transmission and eight oil-fired Babcock & Wilcox boilers rated at 26,800 shaft horsepower (20,000 kW), generating a top speed of 21 knots (39 km/h; 24 mph). The ship had a cruising range of 8,000 nautical miles (15,000 km; 9,200 mi) at a speed of 10 kn (19 km/h; 12 mph). Her crew numbered 57 officers and 1,026 enlisted men. As built, she was fitted with two lattice masts with spotting tops for the main gun battery.[2][3]

The ship was armed with a main battery of twelve 14-inch (356 mm)/50 caliber guns[Note 1] in four, three-gun turrets on the centerline, placed in two superfiring pairs forward and aft of the superstructure. Unlike earlier American battleships with triple turrets, these mounts allowed each barrel to elevate independently.[2] Since Tennessee had been completed after the Battle of Jutland, which demonstrated the value of very long-range fire, her main battery turrets were modified while still under construction to allow elevation to 30 degrees.[4] The secondary battery consisted of fourteen 5-inch (127 mm)/51 caliber guns mounted in individual casemates clustered in the superstructure amidships. Initially, the ship was to have been fitted with twenty-two of the guns, but experiences in the North Sea during World War I demonstrated that the additional guns, which would have been placed in the hull, would have been unusable in anything but calm seas. As a result, the casemates were plated over to prevent flooding. The secondary battery was augmented with four 3-inch (76 mm)/50 caliber guns. In addition to her gun armament, Tennessee was also fitted with two 21-inch (533 mm) torpedo tubes, mounted submerged in the hull, one on each broadside.[2]

Tennessee's main armored belt was 8–13.5 in (203–343 mm) thick, while the main armored deck was up to 3.5 in (89 mm) thick. The main battery gun turrets had 18 in (457 mm) thick faces on 13 in (330 mm) barbettes. Her conning tower had 16 in (406 mm) thick sides.[2]

Service history

Construction – 1941

The keel for Tennessee was laid down on 14 May 1917 at the New York Naval Shipyard; her completed hull was launched on 30 April 1919. Fitting-out work then commenced, and on 3 June 1920, the completed ship was commissioned into the fleet. Captain Richard H. Leigh served as the ship's first commanding officer. Tennessee then began sea trials in Long Island Sound, which lasted from 15 to 23 October. On 30 October, while moored in New York, one of her 300 kW (400 hp) electric generators exploded and destroyed the turbine, wounding two men. Repair work was completed and problems with her propulsion system that were identified during trials were corrected, and on 26 February 1921, Tennessee got underway for further trials off Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. She then steamed north, headed for Hampton Roads, Virginia, arriving on 19 March. She proceeded to Dahlgren, Virginia for shooting training to calibrate her guns.[4] Maintenance in Boston followed, and two of her 5-inch guns were removed.[5] before the ship moved to Rockland, Maine for full-power trials. With her working up now complete, she stopped in New York before steaming south, transiting the Panama Canal, and joining the Battleship Force, Pacific Fleet, in San Pedro, California on 17 June.[4]

Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, the ships of the Pacific Fleet (re-designated as the Battle Fleet in 1922 and again as the Battle Force in 1931) conducted a routine of training exercises, the annual Fleet Problems, and periodic maintenance. The Fleet Problems began in 1923 and typically involved most major units of the US Navy and involved a variety of tactical and strategic war games, and they were conducted in many different locations, including in the Caribbean Sea, the area around the Panama Canal Zone, the Pacific, and the Atlantic. In early 1922, she took part in fleet maneuvers in the Caribbean that saw the Pacific and Atlantic Fleets combine for large-scale training exercises. The maneuvers included elements of the fleets simulating attacks and defenses of the Canal Zone, Puerto Rico, and Guantanamo Bay Naval Base. The Pacific Fleet returned home in April. Tennessee placed first in 1922 and 1923 for accurate shooting among units of the Battle Fleet, and she earned the Battle "E" award in 1923 and 1924; during this period, her commander was Captain Luke McNamee.[4][6]

The Fleet Problems laid the ground work for the US Navy's campaigns during the Pacific War; among the lessons learned by the fleet's officers was the importance of the developing aircraft carrier force, which proved to be more than a simple scouting element. Combined operations also revealed that the slow 21-knot battleships were a significant hindrance to the much faster carriers and led to the development of the fast battleships of the North Carolina, South Dakota, and Iowa classes. The Battle Fleet conducted joint Army-Navy exercises to evaluate the defenses of Pearl Harbor in 1925 as part of Fleet Problem V, which also included maneuvers off the coast of California. Later that year the fleet steamed across the Pacific to visit Australia and New Zealand on a goodwill tour. The fleet returned to San Pedro in September. A three-month visit to Hawaii began in April 1927.[4][7] In 1928, she had a crane and an aircraft catapult on her fantail to accommodate reconnaissance floatplanes.[8]

Her original 3-inch antiaircraft (AA) battery was replaced by eight 5-inch (127 mm)/25 caliber guns during 1929–1930.[5] Fleet Problems X and XI were held together in the Caribbean in March and April 1930, and following their conclusion Tennessee visited New York for a month before departing for home on 19 May. In June, she embarked on a tour of the Hawaiian islands that lasted for fourteen months, finally returning to California in February 1932. She thereafter conducted routine operations off the west coast for the next year and a half until October 1934, when she crossed back to the Atlantic for further training there. The rest of the 1930s followed the usual routine.[4] In around 1935, the ship received eight .50-cal. M2 Browning machine-guns. In 1940, two 3-inch guns were re-installed, one on either side of the forward superstructure.[9]

Fleet Problem XXI, the last iteration of the series, was held in early 1940; afterward, President Franklin D. Roosevelt ordered that the Battle Force transfer its homeport from San Pedro to Pearl Harbor in response to rising tension with Japan over the latter's waging of the Second Sino-Japanese War. Roosevelt hoped the move would deter further Japanese expansionism. Tennessee steamed to the Puget Sound Navy Yard for repairs before moving to Pearl Harbor, arriving there on 12 August. Fleet Problem XXII was scheduled for early 1941, but it was cancelled due to World War II. Tennessee spent the rest of 1941 with small-scale training operations in the Pacific; by December, she was at anchor in Pearl Harbor with the rest of the fleet.[4][7]

World War II

Pearl Harbor

Tennessee was moored along Battleship Row, to the southeast of Ford Island, on the morning of 7 December when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. The battleship West Virginia was tied up alongside, Maryland was ahead with Oklahoma abreast, and Arizona was astern. The first Japanese attack arrived at about 07:55, prompting Tennessee's crew to go to general quarters; it took some five minutes for the men to get the ship's anti-aircraft guns into action. The ship received orders to get underway to respond to the attack, but before the crew got steam up in her boilers, she was trapped as the other battleships around her received crippling damage. West Virginia was torpedoed and sunk and Oklahoma capsized after being torpedoed. Shortly thereafter, dive bombers arrived overhead and fighters strafed the ships' anti-aircraft batteries. Arizona exploded after being hit by an armor-piercing bomb that detonated her magazines, spilling burning fuel oil into the water. The explosion also showered burning oil over Tennessee's stern, and she was quickly surrounded by fire, which was augmented by oil leaking from West Virginia.[4]

At 08:20, Japanese bombers hit Tennessee twice; both bombs were converted large-caliber naval shells, the same type that had destroyed Arizona, but neither detonated properly. The first partially penetrated the roof of turret III, failing to explode but sending fragments into the turret that disabled one of the guns. The second bomb hit turret II's center gun barrel and exploded, sending bomb fragments flying; one of these fragments killed the captain of West Virginia, Mervyn S. Bennion, who had walked out to the open bridge. The blast disabled all three guns of that turret. Neither bomb inflicted serious damage, but the ship's magazines were flooded to avoid the risk of the fires raging aboard and around the vessel from spreading to them and igniting the propellant charges stored there. By 10:30 the crew had suppressed the fires aboard the ship, though oil still burned in the water around the ship for another two days.[4][10] In an effort to push the burning oil away from the ship, she turned her screws at a speed of 5 knots (9.3 km/h; 5.8 mph). In the course of the battle, Tennessee's anti-aircraft gunners were credited with shooting down or assisting in the destruction of five Japanese aircraft.[4][10][11]

Tennessee remained trapped by the sunken battleships around her until Maryland could be pulled free on 9 December; she had been wedged into the dock by Oklahoma when she capsized and sank. The quays to which Tennessee had been moored had to be demolished to allow her to be towed out, as the sunken West Virginia had similarly forced her into them. This work was completed by 16 December, allowing the ship to be pulled slowly out past West Virginia and Oklahoma. She was then taken into the Pearl Harbor Navy Yard for repairs. The fires had warped her hull plates, damaged seams, and loosened rivets, all of which needed to be repaired before she could get underway for permanent repairs. Once the hull was again watertight and her III turret received a patch cover, she got underway for Puget Sound for permanent repairs on 20 December, in company with Maryland and Pennsylvania, both of which had also received only minimal damage in the attack. The three battleships were escorted by four destroyers.[4]

Repairs, training, and modernization

While en route to the west coast, Pennsylvania left Tennessee and Maryland to head to Mare Island for repairs, while the other two vessels continued on to Puget Sound. They reached the naval yard of 29 December, where permanent repairs and a modernization began. The portions of Tennessee's hull plating and electrical wiring that had been damaged by the fire were replaced and her lattice masts were replaced with tripod masts, which were smaller and thus improved the fields of fire of the ship's anti-aircraft battery. In place of her .50-caliber machine guns, she received a battery of sixteen 1.1 in (28 mm) guns in quadruple mounts and fourteen 20 mm (0.79 in) Oerlikon autocannon. New Mark 11 versions of her 14-inch guns replaced the old Mark 4 barrels. The work was completed by late February 1942, and Tennessee got underway on 25 February with Maryland and the battleship Colorado. The three battleships steamed to San Francisco, where they joined Task Force 1, commanded by Rear Admiral William S. Pye. The ships then began a series of training maneuvers that lasted for several months to prepare for the coming campaigns in the central Pacific.[4][9]

In the immediate aftermath of the Battle of Midway on 5 June, Pye took his ships to sea to defend against a possible incursion by the Japanese fleet after its defeat in the battle. By 14 June, the anticipated attack did not materialize, and so Pye turned his task force back to San Francisco. Task Force 1 went to sea again on 1 August for further training, and later that month Tennessee escorted the carrier Hornet to Pearl Harbor, arriving there on 14 August.[4] Hornet was on her way to the Guadalcanal campaign; Admiral Chester Nimitz did not deploy Tennessee and the rest of Task Force 1 to the campaign owing to their heavy use of fuel oil; at that time in the war, the fleet had just seven tankers available for operations, not enough to operate both the fast carrier task force and Pye's battleships.[12] Instead, Tennessee then steamed back east to Puget Sound for a reconstruction; by this time, her sister California had been brought to Puget Sound to be thoroughly rebuilt after the Pearl Harbor raid, and the navy decided that Tennessee should be similarly modernized.[4]

_1943.jpg)

The work on Tennessee lasted nearly a year, and saw the ship radically altered. New anti-torpedo bulges were installed and her internal compartmentalization was improved to strengthen her resistance to underwater damage. Her superstructure was completely revised, with the old heavily armored conning tower being removed and a smaller tower was erected in its place to reduce interference with the anti-aircraft guns' fields of fire. The new tower had been removed from one of the Brooklyn-class cruisers that had recently been rebuilt. The foremast was replaced with a tower mast that housed the bridge and the main battery director, and her second funnel was removed, with those boilers being trunked into an enlarged forward funnel.[4][13] Horizontal protection was considerably strengthened to improve her resistance to air attack; 3 inches of special treatment steel (STS) was added to the deck over the magazines and 2 inches (51 mm) of STS was added elsewhere.[14]

The ship's weapons suite was also overhauled. She received air-search radar and fire-control radars for her main and secondary batteries, the latter seeing the mixed battery of 51-caliber and 25-caliber 5-inch guns replaced by a uniform battery of sixteen 5-inch/38 caliber guns in eight twin mounts. These were controlled by four Mk 37 directors. The light anti-aircraft battery was again revised, now consisting of ten quadruple 40 mm (1.6 in) Bofors guns and forty-three 20 mm Oerlikons.[4][5] The changes doubled the ship's crew, to a total of 114 officers and 2,129 enlisted men.[14] With the reconstruction completed, Tennessee returned to service on 7 May 1943 with a crew composed primarily of recent enlistees and began trials off Puget Sound. On 22 May, she departed for San Pedro to re-join the fleet.[4][11]

The Aleutian Islands

On 31 May, Tennessee and the heavy cruiser Portland steamed out of San Pedro, bound for Adak, Alaska, where they arrived on 9 June.[4] On arrival, Rear Admiral Howard Kingman, the commander of Battleship Division Two, came aboard the ship.[15] The ship joined Task Force 16, which had been organized to support the Aleutian Islands Campaign to recapture the islands of Attu and Kiska from the Japanese. By the time Tennessee arrived, the task force had already retaken Attu, so Tennessee was initially occupied with patrolling for Japanese forces that might launch a counter-attack. American radar operators, including those aboard Tennessee, who were not familiar with operating the new equipment repeatedly made false reports of enemy contacts in the fog that blanketed the area. The supposed enemy contacts were in fact distant land masses that appeared to be ships that were much closer on the radar sets. These false reports culminated in the Battle of the Pips in late July, though Tennessee was not involved in that incident.[4]

On 1 August, Tennessee received orders to approach Kiska and join the pre-invasion bombardment. At 13:10, she steamed into range, along with the battleship Idaho and three destroyers. Tennessee slowed, deployed paravanes from her bow to cut the mooring cables for any naval mines that might be in the area, and launched her Vought OS2U Kingfisher scout planes to spot the fall of her shells. By 16:10, she had closed to a distance of about 7,000 yd (6,400 m) from the beach and she opened fire with her 5-inch guns. Poor visibility hampered the ability of the Kingfishers to observe the ship's fire, but she nevertheless began firing with her 14-inch guns at 16:24. She fired sixty 14-inch shells at the area of what had been a Japanese submarine base before checking her fire at 16:45, by which time visibility had further diminished. After recovering her Kingfishers, she and the rest of the ships steamed back to Adak.[4]

Two weeks later, Tennessee was again sent to shell Kiska early on the morning of 15 August, now to support the landing of ground forces. She opened fire at 05:00, targeting Japanese coastal artillery batteries on Little Kiska Island. She then shifted fire with her main battery to target anti-aircraft batteries on Kiska proper while her 5-inch guns set an artillery observation position on Little Kiska on fire. Following the bombardment, the soldiers were landed, only to discover that the Japanese had already withdrawn from the island in July. Tennessee thereafter left the Aleutians and returned to San Francisco on 31 August, where she conducted extensive training exercises. After replenishing her ammunition and stores, she departed for Hawaii for further battle training. From there, she steamed to the New Hebrides, where the invasion fleet was preparing for operations in the Gilbert Islands.[4]

The Gilbert and Marshall Islands

Battle of Tarawa

The first target of the Gilbert and Marshall campaign was the island of Betio, the main Japanese position in the Tarawa Atoll. In the ensuing Battle of Tarawa that began on 20 November, Tennessee and Colorado provided extensive fire support as the marines struggled to fight their way ashore; while the initial preparatory bombardment had destroyed many crew-served weapons, it had not been sufficient to destroy Japanese beach defenses, a critical lesson the battle taught US forces.[4][15] The two battleships withdrew from the area at nightfall to reduce the risk of a Japanese submarine attack before returning the next morning. The ships provided anti-aircraft support for the invasion fleet and shelled Japanese positions as the marines called in fire support requests. Both vessels withdrew again for the night and returned early on 22 November, by which time the Japanese had been pushed back to a small defensive position on the eastern end of the island. At 09:07, Tennessee began a 17-minute bombardment that saw her fire seventy 14-inch shells and 322 rounds from her secondary guns.[4]

Later that day, the destroyers Frazier and Meade detected the Japanese submarine I-35 and forced her to surface with depth charges. Tennessee's 5-inch guns joined those of the destroyers engaging the submarine, scoring several hits before Frazier rammed and sank I-35. Fighting ashore ended the next day, 23 November, but Tennessee remained in the area until 3 December to guard against a possible Japanese counter-thrust. That evening, she got underway for Hawaii, where on 15 December she joined Colorado and Maryland for the voyage to San Francisco. There, she received a coat of dazzle camouflage and began extensive bombardment training on 29 December. On 13 January 1944, she departed for Hawaii as part of Task Unit 53.5.1, arriving off Maui on 21 January. James Forrestal, then the Undersecretary of the Navy, boarded Tennessee that day, and on 29 January the fleet got underway for the Marshall Islands.[4][15]

Battle of Kwajalein

The next operation, the assault on Kwajalein Atoll in the Marshalls, began on 31 January. Tennessee, Pennsylvania, and two destroyers formed the bombardment group, with Tennessee still serving as Kingman's flagship, and they moved into positions some 2,900 yd (2,700 m) from the atoll's twin islands of Roi-Namur. Tennessee launched her Kingfishers at 06:25 and opened fire at 07:01, targeting pillboxes and other defenses. Her fire was interrupted by a flight of carrier aircraft, which were engaged by Japanese anti-aircraft guns; as soon as the American planes cleared the area, Tennessee shelled the guns and suppressed their fire. She kept up her fire until 12:00, at which point she turned away and recovered her floatplanes to refuel them. With that accomplished, she returned to her firing position and shelled Roi and Namur until 17:00, when she withdrew to cover the escort carriers of the invasion fleet for the night.[4][15]

During the first day's bombardment, marines went ashore onto five smaller islands to secure passage into the lagoon, and minesweepers ensured the entrance was clear for the invasion force. Tennessee, Colorado, and the cruisers Mobile and Louisville steamed into their bombardment positions east of Roi and Namur on 1 February and resumed firing at 07:08 before the marines landed later that morning. Ground forces hit the beaches at around 12:00, and Tennessee and the other ships continued firing to support their advance until 12:45. The marines quickly captured Roi, but the Japanese defenders on Namur put up a strong defense before being defeated the next day. Tennessee steamed into the lagoon later on 2 February, where Vice Admiral Raymond Spruance and Rear Admiral Richard Conolly came aboard to meet with Forrestal, who later went ashore to inspect the battlefield.[4]

Battle of Eniwetok

US forces completed the conquest of the Kwajalein Atoll by 7 February, and preparations for the move to Eniwetok Atoll further west began immediately. That day, Tennessee steamed to Majuro, which had become the US fleet's primary anchorage and staging area in the Marshalls. There, she replenished fuel and ammunition and then returned to Kwajalein, where the invasion fleet was assembling. On 15 February, Tennessee, joined by Colorado and Pennsylvania, sortied in company with the invasion transports, screened by the Fast Carrier Task Force. Cruisers and destroyers conducted the initial bombardment on 17 February while minesweepers cleared the channel into the lagoon. At 09:15, Tennessee led the troopships into the lagoon and approached the initial invasion target, the island of Engebi. Small elements seized nearby islets that would be used as fire bases for field artillery, and late in the day, Tennessee used her secondary battery to support a marine reconnaissance company that set marker buoys to guide the assault craft the next day.[4]

The ship remained in the lagoon overnight and at 07:00, the preliminary bombardment of Engebi began; Tennessee opened fire at 7:33 and the first wave of marines landed at 08:44. The island was quickly secured and forces immediately began to prepare to land at the other islands in the lagoon, primarily the main islands of Eniwetok and Parry Island. Troops landed on the former island after a short preparatory bombardment, and Tennessee spent much of 18 February anchored some 5,500 yd (5,000 m) from the island, bombarding Japanese positions as the marines ground their way across Eniwetok. That night, she fired star shells to illuminate the battlefield and prevent Japanese infiltrators from breaking through American lines. With the fight still raging on Eniwetok, Tennessee was diverted to support the landing on Parry Island with Pennsylvania the next morning.

Anchored just 900 yd (820 m) from the beach, Tennessee opened up a barrage of fire at 12:04 that continued throughout the day and into the morning of 22 February, interrupted only by the need to cease fire during air attacks to avoid accidentally hitting American aircraft. The bombardment leveled the island, demolishing all of the structures and knocking down all of the trees on Parry Island. The ship was so close to the beach that her 40 mm anti-aircraft guns could be used to attack the Japanese defenses. At 08:52 on 22 February, Tennessee checked her fire as the landing craft made their way to the beach. After that interlude, she again provided fire support to the marines as they fought their way through Japanese defenses. The island's garrison quickly fell and the island was pronounced secured that afternoon. As a result of the much heavier bombardments of the Eniwetok campaign, American casualties were significantly lighter than those of Tarawa. The next day, Tennessee departed for Majuro, where she joined the battleships New Mexico, Mississippi, and Idaho and began preparations for the next operation.[4][16]

Bismarck Archipelago

Tennessee and the three New Mexico-class battleships departed on 15 March as part of a task group that included two escort carriers and fifteen destroyers. The group's target was the Japanese base at Kavieng in northern New Ireland, part of the Bismarck Archipelago. The attack was part of the final phase of Operation Cartwheel, the plan to isolate and neutralize the major Japanese base at Rabaul; while Tennessee's unit raided Kavieng as a diversion, a marine force would land on Emirau. An airfield would then be built to complete the encirclement of Rabaul.[4]

The ships arrived off Kavieng on the morning of 20 March. Poor visibility from rain squalls and low clouds masked their approach, and at 07:00 Tennessee launched her Kingfishers. A little over two hours later, Tennessee and the other ships had closed to about 15,000 yd (14,000 m) and at 09:05, they opened fire while steaming at a speed of 15 knots (28 km/h; 17 mph). The ships fired slowly to avoid wasting ammunition, since spotting shots was difficult owing to the weather. A coastal artillery battery took Tennessee under fire once she had closed to about 7,500 yd (6,900 m); her secondary guns replied with rapid fire as the Japanese gunners worked to find the range. Shells splashed close to her starboard side and she was straddled several times, forcing her to increase speed to 18 knots (33 km/h; 21 mph) and turning away to open the range, though she was not hit. She briefly ceased firing before re-engaging the artillery battery for ten minutes, after which no further fire was received.[4][16]

Tennessee and the other battleships and destroyers cruised off Kavieng for another three hours, bombarding Japanese installations and coastal batteries, but the visibility continued to hamper the gunners. At 12:35 the American guns fell silent and the ships withdrew. By that time, the marines had landed on Emirau, which had not been defended by Japanese forces. Tennessee was detached from the fleet to return to Pearl Harbor by way of Purvis Bay and Efate, arriving there on 16 April for periodic maintenance in anticipation of the next major offensive in the Pacific.[4]

The Mariana and Palau Islands

_underway_off_Roi_on_12_June_1944.jpg)

Saipan

The Pacific Fleet began its next major offensive, code-named Operation Forager, the invasion of the Mariana Islands. The fleet was divided into two groups, Task Force 52, which was to attack Saipan and Tinian, and Task Force 53, which would be directed against Guam. Tennessee joined the bombardment group for the former, Task Group 52.17, under the command of Rear Admiral Jesse Oldendorf, which also included California, Maryland, and Colorado. Task Force 52 assembled at Hawaii in mid-May and conducted landing exercises off Maui and Kahoolawe and then steamed to the Marshalls. On 10 June, Task Force 52 sortied to begin the operation, arriving off Saipan three days later. At 04:00 on 14 June, Tennessee and the rest of TG 52.17 began the approach to their bombardment positions off the island; the first ships opened fire at 05:39 and Tennessee joined them nine minutes later. She targeted beach defenses that were engaging minesweepers clearing lanes for the landing craft on the south-western end of the island. Later in the morning, Tennessee attempted to suppress Japanese artillery batteries on Tinian that engaged the bombardment group and had scored hits on California and the destroyer Braine. She then shifted her attention back to the landing zone, finally ceasing fire at 13:31 and withdrawing from the area. She spent the night to the west of the island.[4]

In the early hours of 15 June, the invasion fleet moved into position and at 04:30, TG 52.17 began the pre-landing bombardment. Tennessee held her fire until 05:40, when she unleashed a barrage of shells from her primary, secondary, and 40 mm batteries at a range of 3,000 yd (2,700 m). All shooting ceased at 06:30 to allow the carrier aircraft to make their attacks for the next thirty minutes. TG 52.17 resumed firing at 07:00 and continued until 08:12, when the amtracs and Higgins boats began to make their way to shore. As the marines fought their way ashore, Tennessee remained off the southern end of the landing zone, applying enfilading fire to support their advance. A battery of Japanese 4.7 in (120 mm) field guns hidden in a cave on Tinian opened fire on Tennessee and scored three hits, one of which disabled one of her secondary turrets; the other two did minimal damage and started a small fire. Eight men were killed and another twenty-five were wounded. The ship remained on station supporting the marines on Saipan but that afternoon, withdrew to make temporary repairs and protect the troop transports from the expected Japanese counterattack. She engaged a group of four dive-bombers that attacked the fleet that evening but scored no hits on them.[4]

Tennessee returned to the invasion beach the next morning to resume providing fire support, which she continued into 17 June, helping to clear the way for American advances and to break up Japanese counter-assaults. By this time, Spruance had been informed that the Japanese carrier fleet was approaching, so the fleet reoriented itself to face the threat; Tennessee and the other old battleships moved to protect the invasion fleet transports. The Japanese were defeated by Spruance's carrier force in the ensuing Battle of the Philippine Sea, in which Tennessee did not participate. She refueled east of Saipan on 20 June before returning to the island the next day to resume bombardment duties. Tennessee left the Marianas on 22 June and sailed to Eniwetok, where she met the repair ship Hector for permanent repairs to the damage sustained off Saipan.[4]

Guam and Tinian

The ship remained in Eniwetok until 16 July, when she got underway in company with California, now assigned to TG 53.5, the bombardment group for the invasion of Guam. The ships arrived off Guam three days later and on the morning of 20 July, they joined the bombardment of the island that had begun twelve days before. The ships of TG 53.5 pounded Japanese positions around the island throughout the day. The next morning, they continued the shelling as ground forces stormed the beaches. Tennessee withdrew later in the day and steamed to Saipan on 22 July to replenish her ammunition. Tinian was the next island to be attacked, and Tennessee arrived off that island early the next morning as part of a diversionary bombardment meant to deceive the Japanese defenders as to where the landing would take place. She shelled the southwest coast throughout the morning and afternoon before withdrawing for the night.[4]

Tennessee returned to Tinian on 24 July, this time cruising off the island's northwest coast in company with California, Louisville, and several destroyers. The bombardment group unleashed a flurry of shells from a range of around 2,500 yd (2,300 m) from 05:32 to 07:47, at which point the marines made their assault on the beach. The ships remained on station through 26 July, providing support to the marines as they battled the Japanese defenders. During the bombardment, Tennessee and California flattened Tinian Town with a barrage of 480 rounds from their main batteries and 800 shells from their 5 in guns. Tennessee rotated out to Saipan on 27 July to replenish fuel and ammunition before returning the next day. She once again left for more ammunition at Saipan on 29 July and resumed bombardment duties on the 30th. That morning, one of her Kingfishers accidentally collided with a Marine OY-1 spotting plane, causing both aircraft to crash and killing both aircrews. Fighting ashore continued until the morning of 31 July, and at 08:30, Tennessee ceased firing. After a stop at Saipan, she steamed to Guam, where the battle still raged, to provide fire support until 8 August.[4][16]

Anguar

The ship then got underway with California and Louisville, headed for Eniwetok and then to Espiritu Santo in the New Hebrides, arriving there on 24 August. From there, she moved to Tulagi, where she took part in amphibious assault training. The next major operation would be the reconquest of the Philippines, but to secure the southern flank and capture the Kossol Roads for use as a staging area, the high command decided that the islands of Peleliu and Anguar should be invaded next. Tennessee was assigned to the force tasked with landing at the latter island.[4]

Early on 12 September, the ships of the bombardment group—Tennessee, Pennsylvania, four cruisers, and five destroyers—began the preparatory bombardment of Anguar. She first opened fire with her main and secondary guns at 06:32 at a range of 14,000 yd (13,000 m), but as Japanese defenses were destroyed through the morning, she closed to within 3,750 yd (3,430 m), at which point her 40 mm battery opened fire. The ship was ordered to destroy a large stone lighthouse to prevent the Japanese from using it as an observation post, but after hitting it three times, it remained standing, and so she shifted fire to other targets. Combined with repeated airstrikes from the carriers, the ships hammered Japanese positions around the island for five days. Minesweepers cleared channels to the landing beach on the western coast of the island.[4]

During the bombardment on 15 September, Tennessee was detached to nearby Peleliu to contribute her fire to the landing there. The next day, she returned to Anguar and resumed the bombardment there. Intent on demolishing the lighthouse, Tennessee steamed into position, but while she was training her guns on the target, the light cruiser Denver fired a barrage of 6-inch (150 mm) shells that destroyed the lighthouse. On 17 September, the Army's 81st Infantry Division stormed the beaches, and Tennessee remained offshore to provide fire support for the following two days. The American infantry encountered little serious resistance, and the Japanese garrison had been destroyed by 20 September, allowing Tennessee to steam to Kossol Roads, where she replenished fuel and ammunition. On 28 September, she departed for Manus in the Admiralty Islands to begin preparations for the Philippines operations. There, Rear Admiral Theodore E. Chandler replaced Kingman as the commander of Battleship Division Two.[4][17]

Operations in the Philippines

Leyte

Tennessee began the voyage to the Philippines on 12 October as part of 7th Fleet, commanded by Vice Admiral Thomas Kinkaid. The fleet carried two Army corps that were to land on the eastern coast of Leyte. Tennessee, California, and Pennsylvania were assigned to support the corps that was to land at Dulag; they formed part of the bombardment group that was still under Oldendorf's command. Minesweeping operations to clear paths into Leyte Gulf began on 17 October, and early the next morning Oldendorf sent his force into the gulf shortly after 06:00. They steamed at slow speed, since the minesweepers had not yet completed their task. The ships reached their bombardment positions in the early hours of 19 October, and at 06:45, Tennessee and the other vessels began the bombardment, which lasted throughout the day and prompted little Japanese response, apart from a single bomber that failed to hit any of the ships. At nightfall, the ships withdrew and took up their night stations outside the gulf.[4]

Back in the gulf the next morning, Tennessee resumed firing at 06:00, initially targeting the beaches where the landing craft were to go ashore later that morning. Three and a half hours later, the Higgins boats began their run to the beach, and once they began disembarking troops at 10:00, Tennessee and the other fire support vessels shifted fire further inland to disrupt Japanese counterattacks and prepare the way for the ground troops to advance. The landing triggered the Japanese high command to initiate Operation Shō-Gō 1, a complicated counter-thrust that involved four separate fleets converging on the Allied invasion fleet to destroy it. While the Japanese forces made their way to the Philippines, Tennessee continued to operate off the beachhead; Japanese resistance ashore did not necessitate heavy fire support, but increased air attacks kept Tennessee occupied with providing anti-aircraft defense to the fleet. On the night of 21 October, the transport War Hawk accidentally rammed Tennessee while the latter vessel lay inside a smoke screen. Tennessee was not damaged and there were no injuries. Operations continued uneventfully for the next several days, though on 24 October, the ship's commander received word that the Japanese fleet was expected to attack that night.[4]

Battle of Surigao Strait

On 24 October, reports of Japanese naval forces approaching the area led Oldendorf's ships to prepare for action at the exit of the Surigao Strait. Oldendorf had at his disposal six battleships, eight cruisers, and twenty-eight destroyers.[4] Vice Admiral Shōji Nishimura's Southern Force steamed through the Surigao Strait to attack the invasion fleet in Leyte Gulf; his force comprised Battleship Division 2—the battleships Yamashiro and Fusō, the heavy cruiser Mogami, and four destroyers—and Vice Admiral Kiyohide Shima's Second Striking Force—the heavy cruisers Nachi and Ashigara, the light cruiser Abukuma, and four more destroyers.[18] As Nishimura's flotilla passed through the strait on the night of 24 October, they came under attack from American PT boats, followed by destroyers, initiating the Battle of Surigao Strait, the last battleship engagement in history. One of these US destroyers torpedoed Fusō and disabled her, though Nishimura continued on toward his objective.[19][20]

Observers aboard Tennessee spotted the flashes in the distance as the light American craft attacked Nishimura's force, and at 03:02, her search radar picked up the enemy ships at a range of 44,000 yd (40,000 m). Oldendorf gave the order to open fire at 03:51, and West Virginia opened fire first a minute later, followed by Tennessee and California, concentrating their fire on Yamashiro; the other American battleships had trouble locating a target with their radars and held their fire. Tennessee fired six-gun salvos in an attempt to conserve her limited stock of armor-piercing shells. Yamashiro and Mogami were quickly hit several times by fire from the American battleships and cruisers, suffering severe damage. At about 04:00, Mogami and then Yamashiro turned to retreat, both burning; the destroyer Shigure fled with them, though she had not suffered any serious damage.[4][21][22]

After the initial phase of the battle, the American battle line turned about, but California misinterpreted the vague order to "turn one five" (meaning to turn 150 degrees—California's captain read it as an instruction to turn 15 degrees) and turned incorrectly, passing across Tennessee's bow. By now realizing his mistake, Burnett ordered California to turn hard to starboard while Tennessee hauled out of line. The two ships narrowly avoided each other but in the confusion, California masked Tennessee and blocked her from firing for several minutes. At 04:08, Tennessee fired one last salvo at the fleeing Japanese ships. By this time, several torpedoes launched by the Japanese vessels approached the American line, but none of them struck the battleships.[23] In the course of twelve minutes of shooting, Tennessee had fired 69 armor-piercing shells.[22]

In the meantime, the main Japanese fleet, the Central Force under Vice Admiral Takeo Kurita, had passed through the San Bernardino Strait under cover of darkness and arrived early on 25 October. The Japanese battleships and cruisers attacked Taffy 3, a force of escort carriers and destroyers guarding the invasion fleet in the Battle off Samar, prompting its commander, Rear Admiral Clifton Sprague to make urgent calls for help. Oldendorf immediately turned his ships northward to join the battle, and while en route the ships came under Japanese air attack. By the time the bombardment group arrived on the scene, Kurita had disengaged, having been convinced by Taffy 3's heavy resistance that he was instead facing the far more powerful Fast Carrier Task Force.[4] After the battle, Oldendorf was promoted to the rank of vice admiral and made the commander of Battleship Squadron One, with Tennessee still as his flagship.[24]

Tennessee saw little activity over the next several days, apart from helping to fend off air strikes by Japanese land-based aircraft. The ship received orders on 29 October to leave the Philippines for a thorough overhaul at the Puget Sound Navy Yard. She departed that day with West Virginia, Maryland, and four cruisers, bound for Puget Sound by way of Pearl Harbor.[4] While in Hawaii, Nimitz visited the ship and congratulated the crew on their hard work in the preceding campaigns.[25] She arrived there on 26 November and entered the dry-dock. In addition to periodic maintenance, she received updated fire control radars, including new versions of the Mark 8 radar for her main battery and Mark 12 and Mark 22 systems for her secondary battery. A new SP radar, capable of determining the height of aircraft, was installed to enhance her anti-aircraft capabilities, and her dazzle camouflage was painted over with a dark gray coat that was intended to make her less obvious to the kamikaze pilots who had started to appear over the Philippines. The work was completed by early 1945, and on 2 February, she got underway to rejoin the fleet.[4]

Iwo Jima

En route to join the invasion fleet for the invasion of Iwo Jima in the Bonin Islands, Tennessee stopped in Pearl Harbor and Saipan before joining the bombardment force, now under the command of Rear Admiral William Blandy. The ships reached Iwo Jima early on 16 February and dispersed around the island to their designated firing locations. Poor visibility from rain squalls hampered efforts to direct their fire, which began at 07:07 and continued intermittently through the day, as Blandy had ordered his ships to shoot only when their spotter aircraft could observe impacts to avoid wasting ammunition. Tennessee was tasked with shelling the southeastern corner of the island as well as Mount Suribachi, where the Japanese had installed a battery of four large-caliber guns that Tennessee was to neutralize. The weather had improved on 17 February, permitting the ships to more effectively target the Japanese defenses; Tennessee, Idaho, and the battleship Nevada opened fire at a range of 10,000 yd (9,100 m) before closing to 3,000 yd (2,700 m), pouring crushing fire on various targets around the island for about two hours before breaking off at 10:25. Underwater Demolition Teams (UDT) were sent in to clear beach obstacles and reconnoiter the landing zones, which the Japanese interpreted as the main landing. Dozens of artillery pieces came out of their protective caves and bunkers to engage the UDTs, forcing them to withdraw while the bombardment group resumed firing on the unmasked guns. Tennessee took on wounded men from three of the UDT gunboats to treat them in her sick bay.[4][25]

Tennessee kept up the bombardment through 18 February; over the two days of shelling, she destroyed numerous pillboxes and an ammunition dump and set several fires around the island. The next morning, the troop transports arrived off the island and began preparations to send marines ashore. Tennessee and the rest of the bombardment group, reinforced by the fast battleships North Carolina and Washington and three cruisers, opened up with slow and deliberate fire on the landing beaches. The shooting was interrupted by a carrier strike, after which the ships took up a heavier pace of fire. Just as the marines were about to hit the beach at 09:00, the ships' main batteries ceased firing and their secondaries employed a rolling barrage to clear a path for the marines. As they probed the Japanese defenses and encountered strongpoints, the marines called on Tennessee and other ships to knock them out by way of shore fire control parties that were tied to individual ships.[4]

Tennessee operated off the island for the next two weeks, providing fire as requested from the marines ashore and launching star shells at night to help repel Japanese counterattacks. She was frequently called on to suppress the hidden Japanese guns as they attempted to attack the various support ships around the invasion beach. The ships of the bombardment group experimented with using telescopic sights to aim guns individually, which proved to be particularly effective in destroying point targets such as the Japanese artillery. On 7 March, Tennessee withdrew from the area, having fired some 1,370 shells from her main battery, 6,380 secondary rounds, and 11,481 shells from her 40 mm guns. Fighting raged on Iwo Jima until 26 March, but the fleet needed to begin preparations for the next assault against the island of Okinawa, so Tennessee sailed to the major staging area at Ulithi to replenish ammunition and other supplies. There, she joined the invasion fleet for that operation, consisting of 600 American and British ships.[4][25]

Okinawa

On arriving in Ulithi, Rear Admiral Morton Deyo, the new commander of the bombardment group – which was now designated as Task Force 54 (TF 54) – came aboard Tennessee on 15 March. TF 54 got underway on 21 March and steamed to the Ryuku Islands. The Kerama Islands were their first target; the small group of islands was seized to provide an advanced staging area for the main assault on Okinawa. The bombardment group, which by now included Colorado, Maryland, West Virginia, New Mexico, Idaho, Nevada, and the older battleships New York, Texas, and Arkansas, along with ten cruisers and thirty-two destroyers and destroyer escorts, arrived off the islands five days later. The battleships opened fire at long range, since the minesweepers had not yet cleared the area of mines. The next day, a group of kamikazes struck the fleet, damaging several ships, a harbinger of the steady waves of such attacks over the course of the Okinawa campaign.[4] One plane crashed near Tennessee but did no damage.[25]

After the routine pre-invasion bombardment, the main landing on Okinawa took place on 1 April. Unlike previous assaults, the marines faced no opposition early in the operation; Lieutenant General Mitsuru Ushijima had withdrawn the bulk of his 100,000-strong army to the southern two thirds of the island, where hilly terrain favored the defense. And rather than engage in artillery duels with the battleships, his artillery batteries held their fire until the marines had come further inland. His intention was to delay the invasion as long as possible, thereby keeping the invasion fleet pinned in place as long as possible for the kamikazes that had been massed in the Home Islands for this purpose. On 12 April, the Japanese launched a major strike on the fleet. Tennessee came under attack by five aircraft diving from high altitude; all were shot down before they could hit the ship, but they diverted attention skyward, which allowed an Aichi D3A "Val" dive-bomber to approach at lower altitude, heading straight for Tennessee's bridge. The ship's light anti-aircraft battery opened up on the D3A and damaged it, but not enough to prevent it from crashing into her signal bridge at about 14:50. The impact destroyed a 40 mm mount, fire directors for the 20 mm guns, and hurled burning avgas over the area. The plane carried a 250-pound (110 kg) bomb that penetrated the deck and exploded. The kamikaze killed 22 and wounded another 107 according to the Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships, or killed 25 and wounded 104, according to William Cracknell.[4][25][26]

Later that night, Tennessee and Idaho came under submarine attack, but they narrowly evaded the torpedoes in the darkness.[27] The evacuation transport Pinkney took off Tennessee's wounded, and the dead were buried at sea the next day. After completing emergency repairs, the ship returned to the firing line on 14 April, remaining there for the next two weeks. Deyo transferred to one of the cruisers on 1 May, allowing Tennessee to detach for repairs at Ulithi, which were carried out by the repair ship Ajax. Damaged plating in the superstructure was cut away and replaced and new anti-aircraft guns were installed in place of those that had been destroyed in the attack. Back underway again on 3 June, she returned to Okinawa, arriving six days later. By this time, the campaign was in its final stage; the kamikaze force had been expended and the marines and soldiers had begun the final push to conquer the southern part of the island where the last organized resistance held out. Tennessee added her firepower to the effort over the next several days, bombarding Japanese positions until 21 June when the island was declared secure.[4]

Oldendorf, by now promoted to Vice Admiral, was placed in command of all naval forces in the area, and he made Tennessee his flagship. On 23 June, she embarked on a series of patrols in the East China Sea, searching for Japanese shipping in the area. From 26 to 28 July, she took part in a raid into the Yangtze estuary off Shanghai, China, while escort carriers launched strikes against Japanese positions in occupied China. Oldendorf's ships, including Tennessee, launched a raid on Wake Island before returning to the East China Sea, where the ships remained until the war ended in August. By this time, the fleet had begun preparations for the planned invasion of Japan.[4][28]

With the war over, Tennessee was tasked with covering the landing of occupation troops at Wakayama, Japan, arriving there on 23 September. She then steamed to Yokosuka, where her crew inspected one of the Japanese fleet's main naval bases. On 16 October, she departed for Singapore, where Oldendorf transferred to the cruiser USS Springfield; from there, Tennessee crossed the Indian Ocean, rounded the Cape of Good Hope, and steamed up the Atlantic to the Philadelphia Navy Yard, which she reached on 7 December. This route had been dictated by her 1943 rebuild, as the large anti-torpedo blisters had increased her beam too greatly to allow her to pass through the Panama Canal. In the course of the war, Tennessee had fired a total of 9,347 shells from her main battery, 46,341 shells from her 5-inch guns and more than 100,000 rounds from her antiaircraft battery.[4]

Postwar fate

On 8 December, Tennessee was assigned to the Philadelphia Group of the Sixteenth Fleet, an inactive formation. Immediately after the war, the Navy began a major reduction in force to adjust back to a peacetime footing. Tennessee was by then nearing thirty years in age, but the Navy decided that she was still useful and so she was assigned to the reserve fleet in 1946. Accordingly, the ship needed to be preserved to remain in good condition while in reserve, and the large number of vessels that needed such work slowed the process, so Tennessee was not ready to be formally decommissioned until 14 February 1947. She remained laid up in reserve for twelve years, by which time the Navy decided that she no longer held value as a warship, and so on 1 March 1959, she was stricken from the Naval Vessel Register. She was sold for scrap to Bethlehem Steel on 10 July, was towed to Baltimore, Maryland on 26 July, and was thereafter broken up.[4][27]

Footnotes

Notes

- /50 caliber refers to the length of the gun in terms of caliber. The length of a /50 caliber gun is 50 times its bore diameter.

Citations

- Cracknell, p. 198.

- Gardiner & Gray, p. 117.

- Friedman, p. 443.

- DANFS.

- Breyer, p. 226.

- Cracknell, pp. 207–210.

- Cracknell, p. 210.

- Cracknell, p. 201.

- Cracknell, p. 206.

- Wallin, pp. 193–194.

- Cracknell, p. 212.

- Hornfischer, p. 22.

- Gardiner & Chesneau, p. 92.

- Friedman, p. 444.

- Cracknell, p. 213.

- Cracknell, p. 214.

- Cracknell, p. 216.

- Tully, pp. 24–28.

- Tully, p. 152.

- Cracknell, p. 217.

- Tully, pp. 195–196.

- Cracknell, p. 218.

- Tully, pp. 208–210, 215–216.

- Cracknell, pp. 218–219.

- Cracknell, p. 219.

- Utley, pp. 127–129.

- Cracknell, p. 220.

- Rohwer, pp. 423–424.

References

- Breyer, Siegfried (1973). Battleships and Battle Cruisers 1905–1970. New York: Doubleday and Company. ISBN 0-385-07247-3.

- Cracknell, William H. (1972). "USS Tennessee (BB-43)". Warship Profile 21. Windsor: Profile Publications. pp. 197–220. OCLC 249112905.

- Friedman, Norman (1985). U.S. Battleships: An Illustrated Design History. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-715-1.

- Gardiner, Robert & Chesneau, Roger, eds. (1980). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships, 1922–1946. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-913-9.

- Gardiner, Robert & Gray, Randal, eds. (1985). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships: 1906–1921. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-907-8.

- Hornfischer, James D. (2011). Neptunes Inferno. New York: Bantam Books. ISBN 978-0-553-80670-0.

- Rohwer, Jürgen (2005). Chronology of the War at Sea 1939–1945 – The Naval History of World War Two. London: Chatham Publishing. ISBN 978-1-59114-119-8.

- "Tennessee V (Battleship No. 43)". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Navy Department, Naval History and Heritage Command. 18 February 2016. Retrieved 2 April 2019.

- Tully, Anthony P. (2009). Battle of Surigao Strait. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-35242-2.

- Utley, Jonathan G. (1991). An American Battleship at Peace and War: The U.S.S. Tennessee. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-0492-0.

- Wallin, Homer N. (1968). Pearl Harbor: Why, How, Fleet Salvage and Final Appraisal. Washington, D.C: Department of the Navy. ISBN 0-89875-565-4.

Further reading

- Wright, Christopher C. (1986). "The U.S. Fleet at the New York World's Fair, 1939: Some Photographs from the Collection of the Late William H. Davis". Warship International. XXIII (3): 273–285. ISSN 0043-0374.

External links

![]()