Kiska

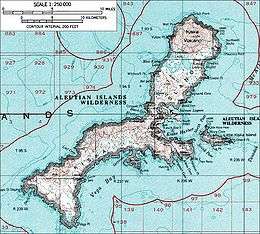

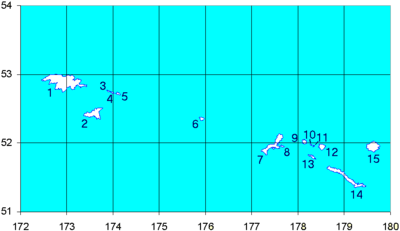

Kiska (Aleut: Qisxa,[1] Russian: Кыска) is an island in the Rat Islands group of the Aleutian Islands of Alaska. It is about 22 miles (35 km) long and varies in width from 1.5 to 6 miles (2.4 to 9.7 km). It is part of Aleutian Islands Wilderness and as such, special permissions are required to visit it.[2] The island has no permanent population.

| Native name: Qisxa | |

|---|---|

A topographical map of Kiska | |

| Geography | |

| Coordinates | 51°57′51″N 177°27′36″E |

| Archipelago | Rat Islands group of the Aleutian Islands |

| Area | 107.22 sq mi (277.7 km2) |

| Length | 22 mi (35 km) |

| Width | 1.5 mi (2.4 km) - 6 mi (10 km) |

| Highest elevation | 4,004 ft (1,220.4 m) |

| Highest point | Kiska Volcano |

| Administration | |

United States | |

| State | Alaska |

| Census Area | Aleutians West Census Area |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 0 (2010) |

History

European Discovery (1741)

In 1741 while returning from his second voyage at sea during the Great Northern Expedition, Danish-born Russian explorer Vitus Bering made the first European discovery of most of the Aleutian Islands, including Kiska. Georg Wilhelm Steller, a naturalist-physician aboard Bering's ship, wrote:

On 25 October 1741 we had very clear weather and sunshine, but even so it hailed at various times in the afternoon. We were surprised in the morning to discover a large tall island at 51° to the north of us.[3]

Prior to European contact, Kiska Island had been densely populated by native peoples for thousands of years.[4] [5]

After Discovery (1741–1939)

Kiska, and the other Rat Islands, were reached by independent Russian traders in the 1750s. After the initial exploitation of the sea otter population, Russians rarely visited the island as interest shifted further east. Years would frequently pass without a single ship landing.[6]

Starting in 1775, Kiska, the Aleutian Islands, and mainland Alaska became fur trading outposts for the Russian-American Company managed by Grigory Shelekhov.

In 1867, U.S. Secretary of State William H. Seward negotiated the purchase of Alaska with the Russian Empire. Kiska was included in the purchase.

World War II (1939–1945)

As one of the only two invasions of the North America during World War II, the Japanese No. 3 Special Landing Party and 500 marines went ashore at Kiska on June 6, 1942 as a separate campaign concurrent with the Japanese plan for the Battle of Midway. The Japanese captured the sole inhabitants of the island: a small United States Navy Weather Detachment consisting of ten men, including a lieutenant, along with their dog. (One member of the detachment escaped for 50 days. Starving, thin, and extremely cold, he eventually surrendered to the Japanese.) The next day the Japanese captured Attu Island.

The military importance of this frozen, difficult-to-supply island was questionable, but the psychological impact upon the Americans of losing U.S. soil to a foreign enemy for the first time since the War of 1812 was tangible. During the winter of 1942–43, the Japanese reinforced and fortified the islands—not necessarily to prepare for an island-hopping operation across the Aleutians, but to prevent a U.S. operation across the Kuril Islands. The U.S. Navy began operations to deny Kiska supply which would lead to the Battle of the Komandorski Islands. During October 1942, American forces undertook seven bombing missions over Kiska, though two were aborted due to inclement weather. Following the winter, Attu was recaptured, and bombing of Kiska resumed for over two months, until a larger American force was allocated to defeat the expected Japanese garrison of 5,200 men.

The Japanese, aware of the loss of Attu and the impending arrival of the larger Allied force, successfully removed their troops on July 28 under the cover of severe fog, without being detected by the Allies.

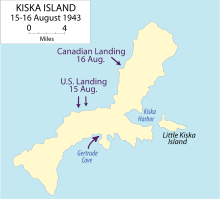

On August 15, 1943, an invasion force consisting of 34,426 Allied troops, including elements of the 7th Infantry Division, 4th Infantry Regiment, 87th Mountain Infantry Regiment, 5,300 Canadians (mainly the 13th Canadian Infantry Brigade from the 6th Infantry Division, with supporting units including two artillery units from the 7th Infantry Division), 95 ships including three battleships and a heavy cruiser, and 168 aircraft landed on Kiska, only to find the island completely abandoned.

Allied casualties during this invasion nevertheless numbered close to 200, all either from friendly fire, booby traps set out by the Japanese to inflict damage on the invading allied forces, or weather-related disease. As a result of the brief engagement between U.S. and Canadian forces, there were 28 American and four Canadian dead.[7] There were an additional 130 casualties from trench foot alone. The destroyer USS Abner Read hit a mine, resulting in 87 casualties.

That night the Imperial Japanese Navy warships, thinking they were engaged by Americans, shelled and attempted to torpedo the island of Little Kiska and the Japanese soldiers waiting to embark.[8] Admiral Ernest King reported to the secretary of the Navy, Frank Knox, that the only things that remained on the island were dogs and freshly brewed coffee. Knox asked for an explanation and King responded, "The Japanese are very clever. Their dogs can brew coffee."[9]

Present-day (1945–present)

The Japanese occupation site on the island is now considered a National Historic Landmark and is protected under federal law. The island is also a part of the Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge (AMNWR) and contains the largest colony of least auklets (over 1,160,000 birds) and crested auklets. Research biologists from Memorial University of Newfoundland have been studying the impact of introduced Norway rats on the seabirds of Kiska since 2001.[10]

Much of the aftermath of World War II is still evident in Kiska. The slow erosion processes on the tundra have had little effect on the bomb craters still visible both from the ground and in satellite images on the hills surrounding the harbor. Numerous equipment dumps, tunnels (some concrete-lined), Japanese gun emplacements, shipwrecks, and other war relics can be found, all untouched since 1943.

In 1983, a memorial plaque was placed on Kiska by the 87th Mountain Infantry Regiment, inscribed:

To the men of Amphibious Task Force 9 who fell here August 1943 placed here August 1983 by 87th Mountain Infantry Regiment.

On August 22, 2007, the submarine USS Grunion, which disappeared with a crew of 70 during World War II, was found in 1,000 metres (3,281 ft) of water off Kiska.[11][12]

In fiction

Renamed "Skira", the island was used as the setting for the Codemasters video game Operation Flashpoint: Dragon Rising.[13] The fictionalized version of the island is relocated closer to Russia and China, but the island's topography is replicated near-exactly, with elements of the game designed around it, instead of vice versa.

Kiska Volcano

Kiska Volcano (Qisxan Kamgii in Aleut) is an active stratovolcano, 5.3 by 4.0 mi (8.5 by 6.4 km) in diameter at its base and 4,006 feet (1,221 m) high, located on the northern end of Kiska Island.

On January 24, 1962, an explosive eruption occurred, accompanied by lava extrusion and the construction of a cinder cone about 98 feet (30 m) high at Sirius Point on the north flank of Kiska Volcano, 1.9 miles (3.1 km) from the summit of the main cone (Anchorage Daily News, January 30, 1962). A second eruption that produced a lava flow was reported to have occurred on March 18, 1964 (Bulletin of Volcanic Eruptions, 1964).

Since then, the volcano has emitted steam and ash plumes, as well as smaller lava flows.

See also

- List of mountain peaks of North America

- List of volcanoes in the United States

- Report from the Aleutians, a 1943 documentary about the bombing of Kiska during World War II

References

- Bergsland, K. (1994). Aleut Dictionary. Fairbanks: Alaska Native Language Center.

- Sommers, Carl (25 November 1990). "Q and A: Visiting the Aleutians". The New York Times. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- Georg Steller – Journal of a Voyage with Bering, 1741–1742 edited by O. Frost. Stanford University Press, 1993, p. 119, ISBN 0-8047-2181-5

- Funk, Caroline. "Rat Islands Archaeological Research 2003 and 2009: Working Toward an Understanding of Regional Cultural, and Environmental Histories". Arctic Anthropology. 2 (48).

- Pierce, Lydia T. Black; edited by R.A. (1984). Atka, an ethnohistory of the Western Aleutians. Kingston, Ont., Canada: Limestone Press. ISBN 0919642993.

- Black, Lydia (2004). Russians in Alaska. Fairbanks: University of Alaska Press. ISBN 1-889963-05-4.

- "The Battle for Kiska", Canadian Heroes, canadianheroes.org, 13 May 2002,

Originally Published in Esprit de Corp Magazine, Volume 9 Issue 4 and Volume 9 Issue 5

- Webber, Bert (1993). Aleutian Headache. Medford, Oregon: Webb Research Group. pp. 201–202. ISBN 0-936738-69-3.

- Miller, Nathan (1995). War at Sea: A Naval History of World War II. New York: Scribner. pp. 375. ISBN 978-0-684-80380-7. OCLC 32276351.

- Jones, Ian L (2008-05-04). "Kiska2002". Memorial University of Newfoundland. Retrieved 2008-06-05.

- Associated Press (2007-08-24). "Missing WWII Sub Found After 65 Years". CBS News. Retrieved 2008-07-14.

- US Navy (2008-10-03). "Navy confirms sunken sub is Grunion". US Navy. Archived from the original on October 7, 2008. Retrieved 2008-10-06.

- Codemasters (2008-07-26). "Codemasters". Codemasters. Archived from the original on 2008-07-23. Retrieved 2008-07-26.

External links

- Kiska Volcano

- Shipwrecks around Kiska

- The Kiska Memorial

- The Aleutians Campaign

- Library of Congress link

- Alaska Volcano Observatory

- Soldiers of the 184th Infantry, 7th ID in the Pacific, 1943–1945

- Long-term study of the impact of introduced rats on the seabirds (Memorial University of Newfoundland)

- A picture gallery from the journey to locate the U.S. World War II submarine "Grunion" sunk near Kiska

- Photos from Kiska Island, July 2008