Tylopterella

Tylopterella is a genus of eurypterid, a group of extinct aquatic arthropods. Only one fossil of the single and type species, T. boylei, has been discovered in deposits of the Late Silurian period (Ludlow epoch) in Elora, Canada. The name of the genus is composed by the Ancient Greek words τύλη (túlē), meaning "knot", and πτερόν (pteron), meaning "wing". The species name boylei honors David Boyle, who discovered the specimen of Tylopterella.

| Tylopterella | |

|---|---|

| |

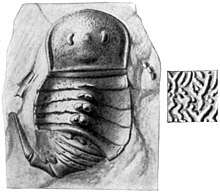

| Top view of the holotype specimen of T. boylei recovered at Elora, in Canada. Carapace ornamentation enlarged. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Subphylum: | Chelicerata |

| Order: | †Eurypterida |

| Superfamily: | †Onychopterelloidea |

| Family: | †Onychopterellidae |

| Genus: | †Tylopterella Størmer, 1951 |

| Type species | |

| †Tylopterella boylei Whiteaves, 1884 | |

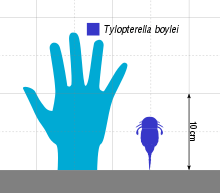

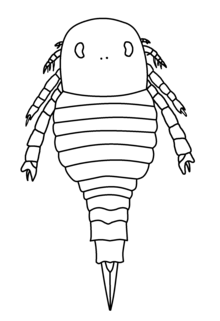

It is a poorly-known genus whose carapace (dorsal plate of the prosoma, head) was semiovate bordered by a marginal rim, with eyes laterally placed, a preabdomen and postabdomen (the two halves of the abdomen) with six segments each and a short spike-like telson ("tail"). It reached a total length of 7.5 centimetres (2.9 inches). These characteristics place Tylopterella in the family Onychopterellidae together with Onychopterella and Alkenopterus.

Tylopterella is notable for its thick ornamentation and general body surface. Its paired tubercles or knobs in the top of its second to fifth segments differentiates it from many other eurypterids. This thickness that its body possessed is due to the highly saline conditions to which Tylopterella had to adapt in the Guelph Formation; other organisms with reinforced shells have also been found in the same place.

Description

Like the other onychopterellids, Tylopterella was a small eurypterid. The total size of the only known specimen is estimated at only 7.5 centimetres (2.9 inches).[1]

Tylopterella is a little-known genus; the type specimen of T. boylei, which conserves the dorsal part of the body, represents its only record thus far. The carapace (dorsal plate of the prosoma, head) had a semiovate (nearly oval) shape, was rounded anteriorly and truncated (shortened as by cutting it) posteriorly and bordered by an highly raised, narrow rim more marked at the sides of the carapace. It was wider than long,[1] and was notable for the extraordinary thickness of its surface and ornamentation.[2] The carapace was 2 cm long (0.8 in) and 2.7 cm wide (1.1 in). The eyes were more or less laterally placed, reniform (bean-shaped) and prominent, with about 0.4 cm (0.16 in) in the greatest diameter and separated between them by 0.6 cm (0.23 in). Equidistantly from the eyes (that is, as far from one eye as from the other), there was a small rounded prominence in which the ocelli (simple eye-like sensory organs) were located. The surface of the carapace was granulose (with granules) and had an ornamentation which consisted of minute rounded tubercles, some isolated and others confluent in sets of two or three. It was strengthened by prominent calcareous (with calcium) deposits.[1]

As in the rest of eurypterids, the opisthosoma (abdomen) had twelve segments.[1] It was divided into the preabdomen (segments 1 to 6), which was telescoped (with segments overlapping each other) and postabdomen (segments 7 to 12).[3] It was thick, short and compact, specially in the two last segments. It was covered by a calcareo-chitinous (with chitin) layer. Each of the second to fifth tergites (dorsal half of the segment) carried in its median line a pair of single large, solid, prominent and elongated tubercles or knobs.[2] They were reniform at the base and somewhat bilobed (with two lobes) at the top. The telson ("tail") was like a gradually narrowing, slightly curved and pointed spine. It reached a length of 1.5 cm (0.6 in).[1] Fragments of the fourth appendage (limb) and the paddle of the swimming leg (sixth and last pair of appendages) are also preserved.[2]

History of research

Tylopterella is known by one single specimen (making it the holotype, GSC 2910, housed at the Museum of the Geological Survey of Canada)[3] preserving the carapace, segments and telson.[2] It was discovered in 1881 in the Guelph Formation, Elora, Canada, by the British blacksmith and archaeologist David Boyle, who for many years collected fossils from the formation. The fossil was brought to the Museum of the Geological Survey of Canada by the trustees (persons in a position of trust) of the Elora School Museum, where it was described by Joseph Frederick Whiteaves, a British paleontologist. He erected a new species of the genus Eurypterus for it, E. boylei, whose specific name honors its discoverer.[1]

In 1912, the American paleontologists John Mason Clarke and Rudolf Ruedemann identified E. boylei as an aberrant form sufficiently different from Eurypterus to have its own subgenus, Tylopterus. This was favored by features like the short and compact body in general or the thick calcareous-chitinous integument of E. boylei, unlike Eurypterus, in which it was only chitinous. They also compared the species with other eurypterid species, Woodwardopterus scabrosus and Hibbertopterus stevensoni, both then part of Eurypterus, in which the ornamentation was also thick and with calcium. This characteristic is also present in gerontic (elder) specimens of Anthraconectes (today recognized as a synonym of Adelophthalmus), but Clarke and Ruedemann denied a close relationship between both subgenera since both lived in very different marine conditions (Anthraconectes lived in brackish or fresh water while Tylopterus lived in very saline water). The name Tylopterus is composed by the Ancient Greek words τύλη (túlē, "knot"), and πτερόν (pteron, "wing"), therefore translated as "knot wing".[2]

In 1951, the Norwegian paleontologist and geologist Leif Størmer replaced the name Tylopterus for Tylopterella as it was a preoccupied name originally coined for the curculionid beetle genus Tylopterus, introduced in 1867 by the French entomologist M. Guillaume Capiomont. Tylopterella would begin to appear in scientific papers as a separate genus from Eurypterus for no apparent reason.[4][5] It was not until 1958 when its status as a separate genus was reaffirmed by the American paleontologist Erik Norman Kjellesvig-Waering, who claimed that Tylopterella differed from any other eurypterid genus by its peculiar ornamentation.[6]

In 1962, a species of Stylonurus, S. menneri, was assigned to Tylopterella by the Russian paleontologist Nestor Ivanovich Novojilov based on the possession of paired tubercles in the tergites, a characteristic dubiously present in only one specimen of S. menneri.[3] However, this species was redescribed in a 2014 study led by the British paleontologist David J. Marshall, determining that it did not represent a eurypterid, but a new chasmataspidid genus which was named Dvulikiaspis, thus rendering Tylopterella monotypic again.[7]

Classification

Tylopterella is classified as part of the family Onychopterellidae, the only clade (group) within the monotypic superfamily Onychopterelloidea. It includes a single species, T. boylei, from the Silurian of the Guelph Formation of Elora, Canada.[1][8]

Originally described as a species of Eurypterus,[1] Tylopterella was recognized as a different subgenus in 1912.[2] In 1951, the British professor Scott Simpson compared the tubercles of Drepanopterus abonensis with those of Tylopterella, recognizing the validity of the genus reluctantly on the basis that the only known specimen of Tylopterella could be referred to both Drepanopterus and Stylonurus.[5] Kjellesvig-Waering identified Tylopterella as a genus of its own, but due to similarities with Erieopterus microphthalmus and E. eriensis, he suggested that T. boylei could have descended directly from Erieopterus.[6] Tylopterella was classified as part of the family Eurypteridae until 1989, when the American paleontologist Victor P. Tollerton classified it as incertae sedis (a taxon with unclear relationships) due to the scarce material and lack of obvious features of any family.[9]

However, in 2011, the British geologist and paleobiologist James C. Lamsdell created the new superfamily Onychopterelloidea and family Onychopterellidae, assigning Tylopterella and Onychopterella to the latter. This family was characterized by the presence of spines in the second to fourth pairs of appendages, lack of spines in the fifth and sixth (except occasionally spurs in the eighth podomere, that is, leg segment of the sixth appendage), the shape of the carapace with lateral eyes and a lanceolate or styliform telson. Lamsdell rejected any alliance between Drepanopterus and Tylopterella.[3] Alkenopterus was assigned to Onychopterellidae three years later because of the detection of a movable spine in the swimming leg, rather than a simple projection (a protuding body part) as previously thought.[10]

The cladogram below is based on a larger study (simplified to only show eurypterids) in a 2011 phylogenetic analysis carried out by Lamsdell, showcasing the basal members of the Eurypterina suborder of eurypterids with other derived groups.[3]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Paleoecology

The only known fossil of Tylopterella was recovered from Ludlovian deposits of Elora in Ontario, Canada.[11] It is thought that the extreme thickness of the body surface of Tylopterella is due to the hypersaline conditions (with salinity levels higher than those of the sea) to which the fauna of the Guelph Formation was exposed and to the life in coral reefs continually hit by waves. Its occurrence with brachiopods and mollusks with thickened shells as well as the matrix of the fossil of Tylopterella, a porous coarse-grained dolomite, indicates the same.[2] Therefore, Tylopterella represents the only eurypterid adapted to hypersalinity.[12]

T. boylei is the only eurypterid found in its fossil site. It is associated with gastropod species such as the trochonematoid Loxoplocus soluta or the anomphaloid Pycnomphalus solarioides, as well as many other indeterminate species of bivalves, bryozoans or cephalopods, among others. The environment in which it lived is considered to be a shallow and subtidal (that is, the sunlight reaches the bottom of the ocean) sea, and its lithology (the physical characteristics of the rocks) consists mainly of dolomite with presence of petroleum.[11]

References

- Whiteaves, Joseph F. (1884). "On some new, imperfectly characterized or previously unrecorded species of fossils from the Guelph Formations of Ontario". Palaeozoic Fossils of Canada. 3 (1): 1–43.

- Clarke, John M.; Ruedemann, Rudolf (1912). The Eurypterida of New York. University of California Libraries. ISBN 978-1125460221.

- Lamsdell, James C. (2011). "The eurypterid Stoermeropterus conicus from the lower Silurian of the Pentland Hills, Scotland". Monograph of the Palaeontological Society. 165 (636): 1–84. ISSN 0269-3445.

- Størmer, Leif (1951). "A New Eurypterid from the Ordovician of Montgomeryshire, Wales". Geological Magazine. 88 (6): 409–422. Bibcode:1951GeoM...88..409S. doi:10.1017/S001675680006996X. Archived from the original on 2018-12-30. Retrieved 2018-12-29.

- Simpson, S. (1951). "A new eurypterid from the upper Old Red Sandstone of Portishead". Annals and Magazine of Natural History. 12: 849–861. doi:10.1080/00222935108654216.

- Kjellesvig-Waering, Erik N. (1958). "The Genera, Species and Subspecies of the Family Eurypteridae, Burmeister, 1845". Journal of Paleontology. 32 (6): 1107–1148. JSTOR 1300776.

- Marshall, David J.; Lamsdell, James C.; Shpinev, Evgeniy S.; Braddy, Simon J. (2014). "A diverse chasmataspidid (Arthropoda: Chelicerata) fauna from the Early Devonian (Lochkovian) of Siberia". Palaeontology. 57 (3): 631–655. doi:10.1111/pala.12080.

- Dunlop, J. A.; Penney, D.; Jekel, D. (2018). "A summary list of fossil spiders and their relatives" (PDF). World Spider Catalog. Natural History Museum Bern.

- Tollerton, Victor P. (1989). "Morphology, taxonomy, and classification of the order Eurypterida Burmeister, 1843". Journal of Paleontology. 63 (5): 642–657. doi:10.1017/S0022336000041275. ISSN 0022-3360. Archived from the original on 2019-03-24. Retrieved 2018-12-29.

- Poschmann, Markus (2014). "Note on the morphology and systematic position of Alkenopterus burglahrensis (Chelicerata: Eurypterida: Eurypterina) from the Lower Devonian of Germany". Paläontologische Zeitschrift. 88 (2): 223–226. doi:10.1007/s12542-013-0189-x.

- "Eurypterid-associated biota of the dolomite of the Lockport Fmn. at Elora, Ont. (Silurian of Canada)". The Paleobiology Database.

- Vrazo, Matthew B.; Brett, Carlton E.; Ciurca, Samuel J. (2016). "Buried or brined? Eurypterids and evaporites in the Silurian Appalachian basin". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 44: 48–59. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2015.12.011.