Türbe

Türbe is the Turkish word for "tomb", in English especially used for the characteristic mausoleums, often relatively small, of Ottoman royalty and Ottoman nobles and notables.

The word is related to the Arabic تُرْبَة turbah (meaning "soil/ ground/ earth"), which can also mean a mausoleum, but more often a funerary complex, or a plot in a cemetery.[1]

Characteristics

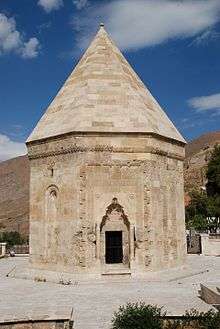

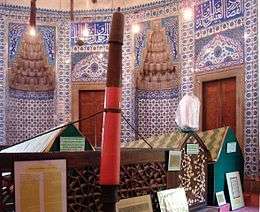

A typical türbe mausoleum is located in the grounds of a mosque or complex, often endowed by the deceased. However, some are more closely integrated into surrounding buildings. They are usually relatively small buildings, often hexagonal or octagonal in shape, containing a single chamber, which may well be decorated with coloured tiles. A dome surmounts the building. They are normally kept closed, but the inside can be sometimes be glimpsed through metal grilles over the windows or door. The exterior is typically masonry, perhaps with tiled decoration over the doorway, but the interior often contains large areas of painted tilework, which may be of the highest quality.

Inside, the body or bodies repose in plain stone sarcophagi, perhaps with a simple inscription, which are, or were originally, covered by rich cloth drapes. In general the sarcophagi are merely symbolic, and the actual body lies below the floor. At the head of the tomb in some examples a wooden pole was surmounted by a white cloth Ottoman turban (for men), or the turban could be in stone.

Earlier examples often had two or more storeys, following the example of the Ilkhanate and Persian tombs on which the style was based; the Malek Tomb is a good example of these. The Ottoman style is also supposed to reflect the shape of the tents used by the earlier nomadic Ottomans, and their successors when on military campaigns. Sultans often built their tombs during their lifetimes, although those of other family members, and some sultans, were built after their deaths. Sultan Murad I, assassinated just after his victory at the Battle of Kosovo in 1389, has his türbe there, with his vital organs, while the rest was carried back to his capital at Bursa, where he has another türbe.

Famous türbes

There are many famous türbes across Istanbul of the various sultans of the Ottoman Empire, as well as of other notables from Turkish history.

Süleymaniye Mosque complex

The Süleymaniye Mosque complex has some of the most famous, including that of Suleiman himself (1550s), perhaps the most splendid Ottoman türbe, and that of his wife Hürrem Sultan, which has extremely fine tilework. Close by to the complex is the türbe of its famous architect Mimar Sinan, in what was his garden.

Konya

Konya holds two earlier türbe, with conical roofs, of the Seljuk Rum dynasty in the Alâeddin Mosque (12th century onwards), and the türbe of Jalal ad-Din Muhammad Rumi, which is a major shrine and pilgrimage point, just like the türbe of Gül Baba in Budapest, Hungary. Bursa, a capital of the earlier Ottomans before the conquest of Constantinople, holds the turbes of many of the earlier Ottoman Sultans including Osman I and his son, the Muradiye Complex containing Murad II and many princes, and the Yeşil Türbe of Mehmed I (died 1421). This is a large three-story tower, and the (false) sarcophagus itself is covered in tiles. Unusually, much of the exterior is covered with undecorated coloured tiles.

Bulgaria

In Bulgaria, the heptagonal türbes of dervish saints such as Kıdlemi Baba, Ak Yazılı Baba, Demir Baba and Otman Baba served as the centers of Bektashi tekkes (gathering places) before 1826.[2] The türbe of Haji Bektash Veli is located in the original Bektashi tekke (now a museum) in the town that now bears his name and remains a site for Alevi pilgrims from throughout Turkey.

Bosnia and Herzegovina

At the peak of the Ottoman empire, under Gazi Husrev-beg Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, became the biggest and most important Ottoman city in the Balkans after Istanbul, with largest marketplace (modern days Baščaršija), and numerous mosques, which by the middle of the 16th century numbered more than 100. By 1660, the population of Sarajevo was estimated to be over 80,000. Husrev-beg greatly shaped the physical city, as most of what is now the Old Town was built during his reign. The Gazi Husrev-beg Mosque (Bosnian: Gazi Husrev-begova Džamija, Turkish: Gazi Hüsrev Bey Camii), is a mosque in Sarajevo historic marketplace Baščaršija, and it was built in 16th century. It is the largest historical mosque in Bosnia and Herzegovina and one of the most representative Ottoman structures in the Balkans. Gazi Husrev-beg's turbe is located in the mosque courtyard.

Travnik, in modern Bosnia and Herzegovina, became the capital of the Ottoman province of Bosnia and residence of the Bosnian viziers after 1699, when Sarajevo was set ablaze by Prince Eugene of Savoy. The Grand Viziers were sometimes buried in Travnik, and türbe shrines were erected in their honour in the heart of Old town of Travnik, where they stand today.

Hungary

The türbe of Idrisz Baba stands in Pécs, Hungary and was built in 1591. It features an octagonal base and domed sepulchre, with ogee-shaped lower windows and circular upper windows on the facade. It is one of only two surviving türbes of its kind in Hungary (the other is the Tomb of Gül Baba), and plays an important role in the record of Ottoman architecture in Hungary.

Not much is known about the Turkish person entombed in the türbe of Idrisz Baba; however, he was considered to be a holy man with the power to work miracles. It was later used as a storage facility for gunpowder. The türbe has been furnished with a mausoleum, embroidered sheet, and prayer mat by the Turkish government. Both the türbe of Idrisz Baba and the türbe of Gül Baba are places of pilgrimage for Muslims.[3]

See also

- Gonbad and Kümbet, Persian and Seljuk equivalents.

- Gongbei (Islamic architecture) (China)

Notes

- Meri, 270

- Lewis, p. 7.

- https://www.iranypecs.hu/en/info/attractions/turkish-age/the-turbe-of-idris-baba.html

References

- Levey, Michael; The World of Ottoman Art, 1975, Thames & Hudson, ISBN 0-500-27065-1

- Lewis, Stephen (2001). "The Ottoman Architectural Patrimony in Bulgaria". EJOS. Utrecht. 30 (IV). ISSN 0928-6802.

- Meri, Josef F., The cult of saints among Muslims and Jews in medieval Syria, Oxford Oriental monographs, Oxford University Press, 2002, ISBN 0-19-925078-2, ISBN 978-0-19-925078-3