Trihecaton

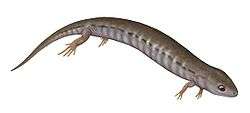

Trihecaton is an extinct genus of microsaur from the Late Pennsylvanian of Colorado. Known from a single species, Trihecaton howardinus, this genus is distinctive compared to other microsaurs due to possessing a number of plesiomorphic ("primitive") features relative to the rest of the group. These include large intercentra (wedge-like components of the vertebrae), folded enamel, and a large coronoid process of the jaw. Its classification is controversial due to combining a long body with strong limbs, features which typically are not present at the same time in other microsaurs. Due to its distinctiveness, Trihecaton has been given its own monospecific family, Trihecatontidae.[1][2]

| Trihecaton | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Subclass: | †Lepospondyli |

| Order: | †"Microsauria" |

| Family: | †Trihecatontidae Vaughn, 1972 |

| Genus: | †Trihecaton Vaughn, 1972 |

| Type species | |

| †Trihecaton howardinus Vaughn, 1972 | |

Discovery

Trihecaton is known from well-preserved fossils discovered in Fremont County, Colorado by a UCLA field expedition in 1970. These fossils were found at a quarry near the town of Howard. The quarry preserved sediments from the Sangre de Cristo Formation, a geological formation dated to the Late Carboniferous period, specifically the Missourian subsection near the end of the Pennsylvanian subperiod. Trihecaton fossils are known from a narrow band of shale in the quarry, a layer known as "Interval 300". The generic name Trihecaton references Interval 300 while the specific name T. howardinus is named after the nearby town.[1]

The holotype fossil, originally called UCLA VP 1743, is a well-preserved skeleton lacking most of the skull and large portions of the hip, hindlimbs, and tail. However, a second fossil, UCLA VP 1744, incorporates a string of tail vertebrae and was found right next to the holotype, indicating that it was probably from the same individual. These fossils were described in 1972 as part of one of Peter Paul Vaughn's reviews of new Sangre de Cristo fauna. Vaughn also named a new family, Trihecatontidae, specifically for the new genus.[1] In 1987, Vaughn's collections were moved to the Carnegie Museum of Natural History,[3] with specimens UCLA VP 1743 and 1744 now known as CM 47681 and 47682.[4]

Description

Most of the skull bones were not preserved, with the exception of both lower jaws as well as a toothed maxilla bone. All of the teeth are slender and conical, and their internal structure has shallowly folded enamel unlike almost all other microsaurs. The teeth are largest right behind the tip of the snout and diminish in size towards the back of the mouth. The complete left mandible was 2.6 centimeters (1.0 inches) in length, indicating that the skull was similar in size. The mandible would have preserved approximately nineteen teeth, further back it rises up into a pronounced coronoid process.[1]

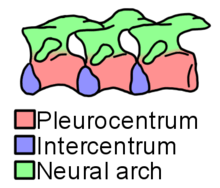

The body was fairly long, with about 36 vertebrae in the presacral vertebral column (i.e. the portion between the head and the hip). The holotype's presacral vertebral column was 16 cm (6.3 inches) long. The presacral vertebrae have plate-like neural spines on top which alternate in appearance. Some neural spines are low and ridge-like while others are taller towards the rear of their respective vertebrae. This switch between "short" and "tall"-type neural spines seems to alternate through most (but not all) of the backbone. The "tall"-type neural spines towards the rear of the body split longitudinally, while those towards the front stay intact. The atlas vertebra was similar to that of other microsaurs, with a central spine-like knob (known as an odontoid process), a pair of adjacent wing-like facets for the braincase, and a deep pit for the notochord visible from behind. The rest of the vertebrae are gastrocentrous, meaning that they have large main portions known as pleurocentra, as well as somewhat smaller crescent-shaped bones known as intercentra, which wedge between the pleurocentra throughout the body. Most microsaurs have diminished or absent intercentra, but Trihecaton has somewhat large ones, albeit not as large as the pleurocentra. Ribs, when preserved, contact both the intercentra and pleurocentra. The ribs are tapered towards the rear of the body and have expanded tips towards the front, although the first few ribs were missing. The referred tail vertebrae are simple, with short neural spines and haemal arches fused to the intercentra.[1]

The interclavicle (the middle element of the shoulder girdle) was broad and T-shaped, with a remarkably short rear prong. The humerus (upper arm bone) was robust and twisted, with a distinct entepicondylar foramen. Other preserved bones of the shoulder and arm were similar to those of the large microsaur Pantylus. The hip was not well preserved, but the femur (thigh bone) was present, with an S-shaped shaft constricted in the middle. The skeletal remains as a whole were covered with thin, oblong scales.[1]

Classification

In various aspects of the general body shape, vertebral construction, and limbs, Trihecaton is clearly a member of a group of lizard-like Paleozoic amphibians called microsaurs. Although it is far from the oldest member of the group, Trihecaton possesses several plesiomorphic ("primitive") features which indicate that it had a very basal position compared to other microsaurs. For example, no other microsaurs possessed large intercentra with rib facets (in the body) or haemal spines (in the tail), though Microbrachis did have small intercentra and Pantylus did have small haemal spines. In addition, Trihecaton's folded enamel is more consistent with larger "labyrinthodonts", a paraphyletic grade of crocodile-like amphibians which the smaller and more specialized microsaurs are probably descended from. The jaw generally resembles that of the eel-like adelogyrinids considering its large coronoid process, which is small in most microsaurs.[1]

Trihecaton's relation to specific microsaur subgroups is uncertain. The elongated body and retention of intercentra is akin to the feeble-limbed microbrachids, but the robust limbs of Trihecaton resemble those of short-bodied microsaurs like pantylids and tuditanids.[1] Carroll & Gaskill (1978) noted that the proportions and intercentra of Trihecaton were also shared with goniorhynchids. However, there is not enough shared material to provide specific comparisons, and in some aspects, such as the construction of the shoulder girdle, Trihecaton clearly differed from goniorhynchids. Carroll & Gaskill preferred not to consider Trihecaton close to any other family of microsaurs, instead considering it an independent relic of the origin of microsaurs.[2]

A series of phylogenetic analyses by Marjanovic & Laurin (2019) included Trihecaton, though with inconclusive results. Like many other studies, they concluded that microsaurs were a paraphyletic grade of amphibians, with most forming a group with a single ancestor, yet a few primitive members (i.e. Microbrachis and Hyloplesion) formed a branch with non-microsaurian holospondyls like diplocaulids and aistopods. Trihecaton jumps between these two branches based on different hypotheses for the position of lissamphibians (modern amphibians like frogs and salamanders). When all lissamphibians are considered to be descended from microsaurs, Trihecaton is equally likely to be close to the Microbrachis + Hyloplesion + Holospondyli branch, or alternatively in the main microsaur group intermediate between ostodolepidids, gymnarthrids, and Saxonerpeton. When lissamphibians are all considered to be temnospondyls unrelated to microsaurs, the structure of Microsauria alters to cement Trihecaton as closer to the Microbrachis branch. Oddly enough, re-adding caecilians to Microsauria moves Trihecaton much closer to ostodolepidids and gymnarthrids. This is also the position found by a bootstrap and bayesian analyses of Marjanovic & Laurin's data.[4] Evidently there is still a lack of resolution for Trihecaton's position, especially considering how interpretations of lissamphibian origins differ wildly between different amphibian-oriented paleontologists.

References

- Vaughn, Peter Paul (23 February 1972). "More vertebrates, including a new microsaur, from the upper Pennsylvanian of Central Colorado". Contributions in Science. 223: 1–19.

- Carroll, Robert L.; Gaskill, Pamela (1978). The Order Microsauria. Philadelphia: The American Philosophical Society. ISBN 978-0871691262.

- Berman, David S.; Sumida, Stuart S. (15 November 1990). "A new species of Limnoscelis (Amphibia, Diadectomorpha) from the late Pennsylvanian Sangre de Cristo Formation of Colorado". Annals of the Carnegie Museum. 59 (4): 303–341.

- Marjanović, David; Laurin, Michel (2019-01-04). "Phylogeny of Paleozoic limbed vertebrates reassessed through revision and expansion of the largest published relevant data matrix". PeerJ. 6: e5565. doi:10.7717/peerj.5565. ISSN 2167-8359. PMC 6322490. PMID 30631641.

See also

- Prehistoric amphibian

- List of prehistoric amphibians