Westlothiana

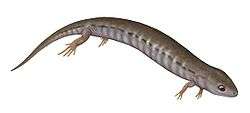

Westlothiana ("animal from West Lothian") is a genus of reptile-like tetrapod that lived about 338 million years ago during the latest part of the Visean age of the Carboniferous. Members of the genus bore a superficial resemblance to modern-day lizards. The genus is known from a single species, Westlothiana lizziae. The type specimen was discovered in the East Kirkton Limestone at the East Kirkton Quarry, West Lothian, Scotland in 1984. This specimen was nicknamed "Lizzie the lizard" by fossil hunter Stan Wood, and this name was quickly adopted by other paleontologists and the press. When the specimen was formally named in 1990, it was given the specific name "lizziae" in homage to this nickname.[1] However, despite its similar body shape, Westlothiana is not considered a true lizard. Westlothiana's anatomy contained a mixture of both "labyrinthodont" and reptilian features, and was originally regarded as the oldest known reptile or amniote.[2] However, updated studies have shown that this identification is not entirely accurate. Instead of being one of the first amniotes (tetrapods laying hard-shelled eggs, including synapsids, reptiles, and their descendants), Westlothiana was rather a close relative of Amniota.[3] As a result, most paleontologists since the original description place the genus within the group Reptiliomorpha, among other amniote relatives such as diadectomorphs and seymouriamorphs.[4][5] Later analyses usually place the genus as the earliest diverging member of Lepospondyli, a collection of unusual tetrapods which may be close to amniotes or lissamphibians (modern amphibians like frogs and salamanders), or potentially both at the same time.[4]

| Westlothiana | |

|---|---|

| Type specimen of Westlothiana lizziae | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Reptiliomorpha |

| Subclass: | †Lepospondyli |

| Genus: | †Westlothiana Smithson and Rolfe, 1990 |

| Type species | |

| Westlothiana lizziae Smithson and Rolfe, 1990 | |

Description

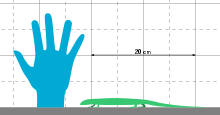

This species probably lived near a freshwater lake, and probably hunted for other small creatures that lived in the same habitat. It was a slender animal, with rather small legs and a long tail. Together with Casineria, another transitional fossil found in Scotland, it is one of the smallest reptile-like amphibians known, being a mere 20 cm in adult length. The small size has made it a key fossil in the search for the earliest amniote, as amniote eggs are thought to have evolved in very small animals.[6][7] It shares many features with reptiles and other early amniotes rather than most amphibious tetrapods of its age. These include a lower number of ankle bones, no labyrinthodont infolding of the dentin, the lack of an otic notch, and a generally small skull.[8] Many of these features are also present in lepospondyls. Ruta et al. (2003) interpreted the long body and small legs as a possible adaption to burrowing, similar to that seen in modern skinks.[4]

Members of Westlothiana were heavily scaled, with thin scales on the belly and many rows of thick, overlapping scales on the back.[3]

Skull

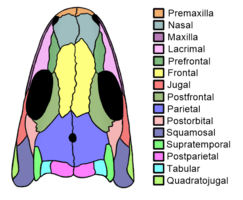

The skull was small compared to the overall body length, and although flattened in both known specimens, many components are visible. Components that were initially hidden by the crushing, such as the palate (roof of the mouth), were later revealed by further preparation and X-ray scans.[3] The orbits (eye sockets) were quite large, each filled with a sclerotic ring. The skull was fairly broad, but not as shallow as in more basal tetrapods. The teeth are all the same size, unlike the case in many early amniotes which have larger fang-like teeth in the middle of the mouth. In addition, they lack "labyrinthodont" internal folding, as with lepospondyls and amniotes, but unlike the case with larger reptiliomorphs. However, this trait may be correlated with size, and not necessarily relations. The lower jaw was similar to that of amniotes in terms of the pattern of component bones. The quadrate bone of the jaw joint is vertical, rather than slanted as in basal reptiliomorphs such as seymouriamorphs and embolomeres.[3]

The bones of the skull roof (the upper part of the skull, behind the eyes) were characteristic in several ways. They were loosely attached to those of the cheek region (namely the squamosal bones), as with amniotes and most reptiliomorphs, except for basal groups in which this area retains a large otic notch rather than contact. The skull roof was primarily composed of the characteristically large and wide parietal bones, which extended to the outer edge of the skull roof, an area known as the temporal region of the skull. The rear edge of the skull roof is formed by three pairs of bones, the postparietals, tabulars, and supratemporals (listed from inwards to outwards). The postparietals are wide, the tabulars are small and square-shaped, and the supratemporals are narrow. This inward-to-outward series is similar to protorothyridids but very different from the condition in microsaurs.[3] The possession of supratemporals is rare among lepospondyls, but it does occur in urocordylids and a few early aistopods, in which the shape of this bone is similar to that of Westlothiana. Each supratemporal contacts the elongated postorbital bone behind the orbit, therefore cutting off the parietals from the squamosals. This contrasts with sauropsids (reptiles), but is similar to the condition in diadectomorphs and early synapsids. Microsaurs do not possess supratemporals, but in most members of the group, their large tabular bones disable parietal-squamosal contact.[9] In more basal reptiliomorphs, this issue did not occur because an additional bone known as an intertemporal was present at the intersection of the four bones. Most reptiliomorphs which lost the intertemporal filled the space using a 'lappet' of the parietal bones. However, in Westlothiana, Limnoscelis, and lepospondyls, this space is filled by an expansion of the rear branch of the postorbital bone.[3][9] This provides evidence for the placement of Westlothiana into lepospondyls.[4]

One of Westlothiana's autapomorphies (unique features) of the skull is the fact that the postfrontal bones, which typically occupy the upper rear corner of the orbits, are very elongated. They stretch forward to form almost the entire upper rim of the eye sockets, and possibly contact the prefrontal bones at the front edge of each socket. This level of contact is uncertain, and may be so slight that it can occur on one side of the skull and not the other. Nevertheless, the possession of any amount of contact between the prefrontal and postfrontal is a primitive feature lost by true amniotes.[3]

Palate

Although the skull in general possesses a combination of amniote and non-amniote features, the palate noticeably lacks amniote adaptations. Most of these missing adaptations relate to the pterygoid bones, which are elongated blade-like structures that lie along the middle of the palate. The palate lacks "labyrinthodont" features such as large fangs, and instead the pterygoids are completely covered with small tooth-like prickles known as denticles. This is unusually primitive compared to early amniotes, which typically have denticles concentrated in only a few parts of the pterygoids. Several rows of denticles are also present along the palatine bones along the rim of the mouth, but apparently not the ectopterygoid bones immediately behind the palatines. The rear of the palate possesses a bone known as a parasphenoid, which has acquired an unusually complex dart-like shape. The pterygoids each have a thin rear branch that reaches as far back as the jaw joints, while further towards the front of the skull they converge together. Perhaps the most notable feature of the palate is the fact that the rear branches of the pterygoids are simple, with concave outer edges. This is in notable contrast to all early amniotes, in which this area possesses an outward prong (known as a 'transverse flange') which is covered with teeth. Further preparation of the skull to reveal this feature of the palate is one of the primary reasons why Westlothiana's classification was reworked to belong outside Amniota.[3]

Postcranial skeleton

The body is elongated, with about 36 to 40 vertebrae between the skull and the hip. No known specimen of Westlothiana preserves a complete tail, so the length of that region is unknown. The vertebrae of the body are multi-part bones, primarily formed by a large pleurocentrum bone at the rear of each segment, with a smaller intercentrum at the front of each segment. Vertebrae which possess this format are defined as "gastrocentrous". The pleurocentra are spool-shaped cylinders, pierced by a large canal for the spinal cord and fused to low, triangular neural spines. The intercentra are crescent-shaped, and despite being smaller than the pleurocentra, they are relatively large compared to those of most amniotes and advanced reptiliomorphs. Overall the vertebrae of Westlothiana most closely resemble those of the early sauropsid Captorhinus, although the short neural spines are more similar to lepospondyl vertebrae.[4] However, the vertebrae also possess a unique feature not shared by any other reptiliomorphs. This feature is the presence of several large keels which run along the underside of each pleurocentrum. Although keels also run along the underside of the pleurocentra in synapsids, these keels are much closer to the midline in members of that group compared to in Westlothiana. The ribs of Westlothiana connect to the intercentra, and are present in every vertebra between the skull and the hip.[3]

The forelimb was significantly shorter than the hindlimb, a characteristic shared with lepospondyls. The only well-preserved portions of the shoulder girdle were the scapulocoracoids (shoulder blades), which were large and robust. The humerus is simple and thinnest in the middle, more similar to microsaurs and early amniotes rather than larger tetrapods. The ulna is similar to that of gracile "pelycosaurs", including small species of Dimetrodon such as D. milleri. Although the hand of Lizzie was disarticulated, four metacarpal bones could be identified. This indicates that members of Westlothiana possessed at least four, and possibly even five fingers.[10] Practically all other reptiliomorphs possessed five-fingered hands, except for the majority of lepospondyls. Lepospondyls (with the exception of Diceratosaurus and Urocordylus) possessed four or fewer fingers. Analyses which consider Westlothiana to possess only four fingers generally agree that it is a lepospondyl.[11][4]

The pelvis (hip) is large, with the upper portion formed by a rod-shaped ilium and the lower portion formed by a narrow and long "puboischiadic plate". The rear portion of the puboischiadic plate is particularly elongated in Westlothiana compared to in other reptiliomorphs, but the other parts of the pelvis are fairly normal by the group's standards. The femur is long and robust, and is also thinnest in the middle as with the humerus. Also similar to the humerus, the femur's crests and roughened areas for muscle attachment are large considering the small size of the animal. Although the femur is generally similar to that of synapsids, the tibia and fibula are much more simple and primitive. In addition, they are noticeably smaller than the femur, a condition reversed to the trend in most reptiliomorphs leading to amniotes.[3]

Ankle and foot

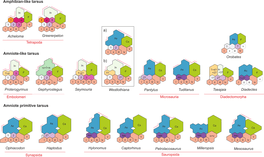

The ankle of Westlothiana was similar (but probably not identical) to that of basal amniotes, rather than amphibians. In modern amphibians and most non-amniote tetrapods, the ankle is formed by twelve bones. Five small, rounded ankle bones, known as "distal tarsals", connect to the metatarsal bones which each lead to a toe. Three somewhat larger ankle bones, known as "proximal tarsals", connect to the bones of the lower leg. These three are the medium-sized fibulare (which connects to the fibula), the small tibiale (which connects to the tibia), and the quite large intermedium which lies in the middle and contacts both the fibula and tibia. Four small numbered bones known as "centralia" fill in the gaps between the proximal and distal tarsals.[12]

In basal amniotes, the condition is quite different, with the ankle only formed by eight bones. The five distal tarsals are typically unchanged, but usually only a single centrale is preserved. This single remaining centrale, referred to as the "navicular" bone, was either formed by the retention of only the second centrale or the fusion of the first and second. Amniotes are also very different from amphibians in the fact that they possess only two large proximal tarsals. The calcaneum, which contacts the fibula, is almost unanimously considered to be identical to the fibulare. The other proximal tarsal, the astragalus (or talus), is likely a mass formed by the fusion of the intermedium, tibiale, and the fourth (and possible also the third) centrale. Some lepospondyls, such as the reptile-like microsaur Tuditanus, also may have evolved these modifications.[12]

The ankle of Westlothiana, as well as that of most other "reptiliomorphs", is intermediate between these two conditions. Smithson (1989) reported that "Lizzie" had nine ankle bones, including an astragalus and calcaneum, and that the third and fourth centrales were already fused or lost. Yet he also noted that centrales one and two (which formed the navicular bone) were unfused.[2] Smithson et al. (1993) later claimed that there were ten bones, arguing that the components of the astragalus were not completely fused, with the intermedium and tibiale still separate.[3] Piñeiro, Demarco, & Meneghel (2016) could not determine which of these two interpretations were superior, but did note that the largest bone more closely resembled a fused astragalus rather than an unfused intermedium.[12]

The foot was most likely five-toed, with a phalangeal formula (the number of phalanges per toe from the innermost to outermost toe) of 2-3-4-5-4. This formula is identical to that of early amniotes, but conversely the foot of Westlothiana is shorter and more robust than the long-toed feet of amniotes. Additionally, the phalanges decrease in relative size towards the tip of the foot in this genus, while the opposite is true of amniotes.[3]

Phylogeny

The phylogenetic placement of Westlothiana has varied from basal amniote (i.e. a primitive reptile)[2] to a basal Lepospondyl, in analyses with the lepospondyls branching off from within Reptiliomorpha.[5] The actual phylogenetic position of Westlothiana is uncertain, reflecting both the fragmentary nature of the find and the uncertainty of "labyrinthodont" phylogeny in general.[7]

The modern consensus on the classification of Westlothiana, as supported by analyses such as Clack (2002),[13] Ruta et al. (2003),[4] and Ruta & Coates (2007)[14] considers the genus to be the earliest diverging (most "basal" or "primitive") member of Lepospondyli. Westlothiana's placement in Lepospondyli supports the hypothesis that lepospondyls are not very distant from amniotes. However, modern lissamphibians are sometimes considered to be descended from lepospondyls. Therefore, Westlothiana may actually be closer to modern amphibians than to amniotes, although still close to both.

See also

External links

References

- Smithson, T.R. & Rolfe, W.D.I. (1990): Westlothiana gen. nov. :naming the earliest known reptile. Scottish Journal of Geology no 26, pp 137–138.

- Smithson, T. R. (December 1989). "The earliest known reptile". Nature. 342 (6250): 676–678. doi:10.1038/342676a0. ISSN 0028-0836.

- Smithson, T. R.; Carroll, R. L.; Panchen, A. L.; Andrews, S. M. (1993). "Westlothiana lizziae from the Viséan of East Kirkton, West Lothian, Scotland, and the amniote stem". Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. 84 (3–4): 383–412. doi:10.1017/S0263593300006192. ISSN 1755-6929.

- Ruta, M.; Coates, M.I. & Quicke, D.L.J. (2003): Early tetrapod relationships revisited. Biological Reviews no 78: pp 251-345.PDF

- Palmer, D., ed. (1999). The Marshall Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Animals. London: Marshall Editions. p. 62. ISBN 978-1-84028-152-1.

- Carroll R.L. (1991): The origin of reptiles. In: Schultze H.-P., Trueb L., (ed) Origins of the higher groups of tetrapods — controversy and consensus. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, pp 331-353.

- Laurin, M. (2004): The Evolution of Body Size, Cope's Rule and the Origin of Amniotes. Systematic Biology no 53 (4): pp 594-622. doi:10.1080/10635150490445706 article

- Paton R.L., Smithson, T.R. & Clack, J.A. (1999): An amniote-like skeleton from the Early Carboniferous of Scotland. Nature no 398: pp 508–513

- Carroll, Robert L.; Gaskill, Pamela (1978). The Order Microsauria. Philadelphia: The American Philosophical Society. ISBN 978-0871691262.

- Laurin, Michel (1998). "A reevaluation of the origin of pentadactyly". Evolution. 52 (5): 1476–1482. doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.1998.tb02028.x. ISSN 0014-3820. PMID 28565380.

- Laurin, Michel; Reisz, Robert R. (1999). "A new study of Solenodonsaurus janenschi, and a reconsideration of amniote origins and stegocephalian evolution". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 36 (8): 1239–1255. doi:10.1139/e99-036.

- Piñeiro, Graciela; Núñez Demarco, Pablo; Meneghel, Melitta D. (2016-05-17). "The ontogenetic transformation of the mesosaurid tarsus: a contribution to the origin of the primitive amniotic astragalus". PeerJ. 4: e2036. doi:10.7717/peerj.2036. ISSN 2167-8359. PMC 4878385. PMID 27231658.

- Clack, J. A. (2002). "An early tetrapod from 'Romer's Gap'". Nature. 418 (6893): 72–76. doi:10.1038/nature00824. PMID 12097908.

- Ruta, M.; Coates, M. I. (2007). "Dates, nodes and character conflict: addressing the lissamphibian origin problem". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 5 (1): 69–122. doi:10.1017/S1477201906002008.