Chūō Shinkansen

The Chuo Shinkansen (中央新幹線, Central Shinkansen) is a Japanese maglev line under construction between Tokyo and Nagoya, with plans for extension to Osaka. Its initial section is between Shinagawa Station in Tokyo and Nagoya Station in Nagoya, with stations in Sagamihara, Kōfu, Iida, and Nakatsugawa.[2] The line is expected to connect Tokyo and Nagoya in 40 minutes, and eventually Tokyo and Osaka in 67 minutes, running at a maximum speed of 505 km/h (314 mph).[3] About 90% of the 286-kilometer (178 mi) line to Nagoya will be tunnels,[4] with a minimum curve radius of 8,000 m (26,000 ft) and a maximum grade of 4% (1 in 25).

| Chūō Shinkansen | |||

|---|---|---|---|

An L0 Series maglev undergoing testing on the Yamanashi Maglev Test Line in 2013 | |||

| Overview | |||

| Native name | 中央新幹線 | ||

| Type | Maglev | ||

| System | SCMaglev | ||

| Status | Under construction | ||

| Termini | Shinagawa Shin-Ōsaka | ||

| Stations | 9 | ||

| Operation | |||

| Planned opening | Unknown[1] Originally 2027 (Tokyo Shinagawa – Nagoya) and 2037 (Nagoya – Shin-Osaka) | ||

| Owner | JR Central | ||

| Rolling stock | L0 Series | ||

| Technical | |||

| Line length | 285.6 km (177.5 mi) (Shinagawa–Nagoya) 42.8 km (26.6 mi) (current test track) | ||

| Number of tracks | 2 | ||

| Electrification | 33 kV AC, induction | ||

| Operating speed | 505 km/h (314 mph) | ||

| |||

The Chuo Shinkansen is the culmination of Japanese maglev development since the 1970s, a government-funded project initiated by Japan Airlines and the former Japanese National Railways (JNR). Central Japan Railway Company (JR Central) now operates the facilities and research. The line is intended to be built by extending and incorporating the existing Yamanashi test track (see below). The trainsets themselves are popularly known in Japan as linear motor car (リニアモーターカー, rinia mōtā kā), though there have been many technical variations.

Government permission to proceed with construction was granted on May 27, 2011. Construction of the line, which is expected to cost over ¥9 trillion, commenced in 2014.[5]

The start date of commercial service is unknown after Shizuoka Prefecture denied permission for construction work on a portion of the route in June 2020.[1] JR Central had originally aimed to begin commercial service between Tokyo and Nagoya in 2027, with the Nagoya–Osaka section originally planned to be completed by 2045.[6] The government is, however, planning to support a speed-up of the timeline for the construction of the Osaka section by up to 8 years to 2037 with a loan.[7]

Development overview

Miyazaki and Yamanashi Test Tracks

Following the opening of the Tokaido Shinkansen between Tokyo and Osaka in 1964, Japanese National Railways (JNR) focused on the development of faster Maglev technology. In the 1970s, a 7-kilometer (4.3 mi) test track for Maglev research and development was built in Miyazaki Prefecture.[8] As desired results had been obtained at the (now former) Miyazaki test track, an 18.4 kilometer test track with tunnels, bridges and slopes was built at a site in Yamanashi Prefecture, between Ōtsuki and Tsuru (35.5827°N 138.927°E). Residents of Yamanashi Prefecture and government officials were eligible for free rides on the Yamanashi test track, and over 200,000 people took part. Trains on this test track have routinely achieved operating speeds of over 500 km/h (310 mph), making this an embryonic part of the future Chuo Shinkansen.

The track was extended a further 25 km (16 mi) along the future route of the Chuo Shinkansen, to bring the combined track length up to 42.8 km (26.6 mi). Extension and upgrading work was completed by June 2013, allowing researchers to test sustained top speed over longer periods.[9][10] The first tests covering this longer track took place in August 2013.[11][12] JR Central began offering public train rides at 500 km/h on the Yamanashi test track, via a lottery selection, in 2014.[13] The train has the world record for fastest manned train on this track.

Routing

The line's route passes through many sparsely populated areas in the Japanese Alps (Akaishi Mountains), but is more direct than the current Tōkaidō Shinkansen route, and time saved through a more direct route was a more important criterion to JR Central than having stations at intermediate population centers. Also, the more heavily populated Tōkaidō route is congested, and providing an alternative route if the Tōkaidō Shinkansen were to become blocked by earthquake damage was also a consideration. The route will have a minimum curve radius of 8,000 m (26,000 ft), and a maximum gradient of 4%. This is significantly more than the traditional Shinkansen lines, which top out at 3%.

The planned route between Nagoya and Osaka includes a stop in Nara. In 2012, politicians and business leaders in Kyoto petitioned the central government and JR Central to change the route to pass through their city.[14] The governor of Nara Prefecture announced in November 2013 that he had re-confirmed the Transport Ministry's intention to route the segment through Nara.[15]

JR Central announced in July 2008 that the Chūō Shinkansen would start at Tokyo's Shinagawa Station, citing difficulties in securing land at nearby Tokyo and Shinjuku stations for a maglev terminal.[16]

| Plan name | Route between Kofu and Nakatsugawa |

Distance from Tokyo (km) | Construction costs (JPY) from Tokyo | Shortest journey time from Tokyo | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| to Nagoya | to Osaka | to Nagoya | to Osaka | to Nagoya | to Osaka | ||

| Plan A | via Kiso Valley | 334 | 486 | 5.63 trillion | 8.98 trillion | 46 minutes | 73 minutes |

| Plan B | via Ina Valley (Chino, Ina, Iida) | 346 | 498 | 5.74 trillion | 9.09 trillion | 47 minutes | 74 minutes |

| Plan C | under the Japanese Alps and Iida City | 286 | 438 | 5.10 trillion | 8.44 trillion | 40 minutes | 67 minutes |

A JR Central report on the Chuo Shinkansen was approved by a Liberal Democratic Party panel in October 2008, which certified three proposed routes for the Maglev. According to a Japan Times news article, JR Central supported the more direct route, which would cost less money to build than the other two proposals, backed by Nagano Prefecture. The latter two plans had the line swinging up north between Kōfu and Nakatsugawa stations to serve areas within Nagano.[17] In June 2009, JR Central also announced research results comparing the three routes, estimating revenue and travel time, which showed the most favorable being the shortest Plan C, with long tunnels under the Japanese Alps.[18] The Council for Transport Policy for the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism concluded on October 20, 2010 that Plan C would be most cost-efficient.[19] JR Central announced that one station would be constructed in each of Yamanashi, Gifu, Nagano, and Kanagawa Prefectures.[3] On 31 October 2014, Japan's Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism approved Plan C for construction.[20] Construction began on 17 December 2014.[21]

The station in Nagoya was completed in 2016. A skyscraper measuring 220 m (720 ft) in height was built by JR Central. The structure is named "Nagoya-eki Shin-biru" (Nagoya Station new building) and accommodates a station for the maglev trains in its basement area.[22]

Construction schedule and costs

JR Central announced in December 2007 that it planned to raise funds for the construction of the Chuo Shinkansen on its own, without government financing. Total cost, originally estimated at 5.1 trillion yen in 2007,[23] escalated to over 9 trillion yen by of 2011.[5] Nevertheless, the company has said it can make a pretax profit of around 70 billion yen in 2026, when the operating costs stabilize.[24] The primary reason for the project's huge expense is that most of the line is planned to run in a tunnel (about 86% of the initial section from Tokyo to Nagoya will be underground)[25] with some sections at a depth of 40 m (130 ft) (deep underground) for a total of 100 km (62 mi) in the Tokyo, Nagoya and Osaka areas.

The original construction schedule from 2013, which called for the Tokyo–Nagoya segment to open in 2027 and the Nagoya–Osaka segment to open in 2045, was designed to keep JR Central's total debt burden below its approximate level at the time of privatization (around 5 trillion yen). The schedule was later altered to bring forward the completion date of the Nagoya-Osaka segment to 2037, after JR Central received a loan from the government.

The first major contract announced was for a 7 km (4.3 mi) tunnel in Yamanashi and Shizuoka prefectures expected to be completed in 2025.[26] Construction of a 25 km (16 mi) tunnel under the southern Japanese Alps commenced on 20 December 2015, approximately 1,400 m (4,600 ft) below the surface at its deepest point. The tunnel is expected to be completed in 2025, and upon completion will succeed the 1,300 m (4,300 ft) deep Daishimizu Tunnel on the Joetsu Shinkansen line as the deepest tunnel in Japan. Construction has also started on the maglev station at Shinagawa.[27] Being built below the existing Shinkansen station, and to consist of two platforms and four tracks, construction is planned to take 10 years, largely to avoid disruption to the existing Tokaido Shinkansen services located above the new station.

JR Central estimates that Chuo Shinkansen fares will be only slightly more expensive than Tokaido Shinkansen fares, with a difference of around 700 yen between Tokyo and Nagoya, and around 1,000 yen between Tokyo and Osaka. The positive economic impact of the Chuo Shinkansen in reducing travel times between the cities has been estimated at anywhere between 5 and 17 trillion yen during the line's first fifty years of operation.[28]

The Ōi River issue

Construction is yet to commence on the part of the line going through Shizuoka Prefecture, as the municipality has expressed concern about water from the Ōi River leaking into the tunnel, lowering the water level.[29] JR Central has expressed concern early on that the delay on construction of the only 9 kilometer long section going through Shizuoka might throw the entire project off schedule.[30]

Officials of Shizuoka Prefecture, in a meeting with JR Central in June 2020, denied permission to begin construction work on the tunnel. JR Central announced the following week that it would be "difficult" to open the Tokyo-Nagoya line in 2027 as previously announced.[1]

Osaka Extension

The government of Osaka Prefecture, as well as local corporations such as Suntory and Nippon Life, have raised concerns about the impact of the delayed construction of the Nagoya–Osaka segment on the Osaka economy. Politicians from the Kansai region called for, and received, expanded government assistance in order to expedite the line's construction, resulting in the opening of the extension being moved forward by up to 8 years.[15]

Technology

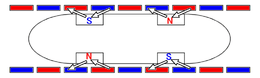

The levitating force is generated between superconducting magnets on the trains and coils on the track.[31] The absence of wheel friction allows normal operation at over 500 km/h, and higher accelerations and deceleration performance compared to conventional high-speed rail. The superconducting coils use Niobium–titanium alloy cooled to a temperature of −269 °C (4.15 K; −452.20 °F) with liquid helium.[31]

Magnetic coils are used both for levitation and propulsion. Trains are accelerated by alternating currents on the ground producing attraction and repulsion forces with the coils on the train. The levitation and guidance system, working with the same principle, ensures that the train is elevated and centered in the track.[31]

Energy consumption

In 2018, a scientific comparison of the energy consumption of SCMaglev, Transrapid and conventional high-speed trains was conducted. Here, the energy consumption per square meter of usable area was examined according to speed.[32] The results show that there are only minor differences at speeds of 200 km/h and above. However, maglevs can reach much higher speeds than trains. Conventional trains, on the other hand, require less energy at slow speeds.[32]

At normal operating speed, the energy consumption of the Maglev train is estimated at 90-100 Wh/(seat km).[33] For comparison, the conventional Shinkansen Nozomi running at normal speed has an energy consumption of 29 Wh/(seat km).[33] However, this is still less than half of even the most efficient short/medium-haul modern passenger aircraft. For instance, the Airbus A319neo uses ~209 Wh/(seat km).[34] Moreover, the operation of the Maglev train is completely electric.

Route

The line has one station for each prefecture it passes through, except for Shizuoka.

| Station name[lower-alpha 1] | Distance from (km) | Connections | Location | Coordinates | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| previous station |

Shinagawa | ||||

| Shinagawa Station | 0.0 | JR Central: Tokaido Shinkansen JR East: Yamanote Line, Keihin-Tohoku Line, Tokaido Line, Yokosuka Line, Sobu Line, Utsunomiya Line, Takasaki Line, Joban Line Keihin Electric Express Railway: Keikyū Main Line |

Tokyo | 35°37′50″N 139°44′28.9″E | |

| Hashimoto Station | JR East: Yokohama Line, Sagami Line Keio Electric Railway: Sagamihara Line |

Sagamihara, Kanagawa Prefecture | 35°35′35.3″N 139°20′42.2″E | ||

| Kōfu Station | Kofu, Yamanashi Prefecture | 35°36′19″N 138°33′41.6″E | |||

| Iida Station | JR Central: Iida Line (New Station Planned) | Iida, Nagano Prefecture | 35°31′36″N 137°51′9.1″E | ||

| Nakatsugawa Station | JR Central: Chuo Main Line | Nakatsugawa, Gifu Prefecture | 35°28′47.2″N 137°26′51″E | ||

| Nagoya Station | 285.6 | JR Central: Tokaido Shinkansen, Tokaido Main Line, Chuo Main Line, Kansai Main Line Nagoya Rinkai Rapid Transit: Aonami Line Nagoya Municipal Subway: Higashiyama Line, Sakura-dori Line Meitetsu: Nagoya Main Line Kintetsu Railway: Kintetsu Nagoya Line |

Nagoya | 35°10′19.7″N 136°52′52.2″E | |

| Mie Prefecture Station | (TBD) | Kameyama, Mie Prefecture | 34°51′01.1″N 136°27′01.6″E | ||

| Nara Prefecture Station | (TBD) | Nara | 34°42′38.5″N 135°48′37.6″E | ||

| Shin-Osaka Station | 438.0 | JR Central: Tokaido Shinkansen JR West: Sanyo Shinkansen, Hokuriku Shinkansen (planned), JR Kyoto Line, JR Kobe Line, JR Takarazuka Line, Osaka Higashi Line, Naniwasuji Line (planned) Hankyu Corporation (planned) Osaka Municipal Subway: Midosuji Line |

Osaka | 34°44′0.54″N 135°30′0.41″E | |

| |||||

Rolling stock

On December 2, 2003, MLX01, a three-car train set a world record speed of 581 km/h (361 mph) in a manned vehicle run. On November 16, 2004, it also set a world record for two trains passing each other at a combined speed of 1,026 km/h (638 mph).

On October 26, 2010, JR Central announced a new train type, the L0 Series, for commercial operation at 505 km/h (314 mph).[35] This model set a world record speed for a manned train of 603 km/h (375 mph) on 21 April 2015.[36]

References

- "JR Central gives up on opening new maglev train service in 2027". Kyodo. 3 July 2020. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

- "中央新幹線(東京都・名古屋市間)計画段階環境配慮書の公表について" (PDF). Central Japan Railway Company. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 June 2011. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- Kyodo News, "JR Tokai to list sites for maglev stations in June", The Japan Times, 2 June 2011, p. 9.

- Smith, Kevin (18 December 2014). "JR Central starts construction on Chuo maglev". International Railway Journal. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

Major construction on the 286km line, 90% of which will be underground or through tunnels, is set to begin in 2015 and the project is due to be completed in 2027.

- "Chuo maglev project endorsed". Railway Gazette International. 27 May 2011.

- "Maglev launch to be delayed to 2027". Asahi Shimbun. 30 April 2010. Archived from the original on 26 October 2010. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- "10-year countdown begins for launch of Tokyo-Nagoya maglev service". The Japan Times Online. 9 January 2017. Retrieved 25 November 2017.

- Taniguchi, Mamoru (1993). "The Japanese Magnetic Levitation Trains". Built Environment. Alexandrine Press. 9 (3/4): 235. JSTOR 23288579. – via JSTOR (subscription required)

- "JR Central unveils L0 maglev". Railway Gazette International. 4 November 2010.

- 7月中にも最高時速500キロに 新型車両「L0系」 [New L0 series trains to reach 500 km/h during July]. Chunichi Web (in Japanese). Japan: The Chunichi Shimbun. 24 July 2013. Archived from the original on 29 July 2013. Retrieved 30 July 2013.

- Hirokazu Tatematsu (29 August 2013). "Test runs get under way on 500 km/h maglev Shinkansen". Asahi Shimbun. Archived from the original on 2013-09-02.

- Hirokazu Tatematsu (30 August 2013). "Maglev train offers smooth ride inside, deafening noise outside". Asahi Shimbun. Archived from the original on 2013-09-02.

- SAWAJI, OSAMU (April 2017). "Tokyo to Nagoya City in 40 Minutes: The coming age of maglev". Highlighting Japan: The New Age of Rail. Public Relations Office of the Government of Japan. Retrieved 2018-03-04.

- Johnston, Eric, "Economy, prestige at stake in Kyoto-Nara maglev battle", The Japan Times, 3 May 2012, p. 3.

- "リニア「同時開業」綱引き 品川―名古屋―新大阪". 日本経済新聞. 6 December 2013. Retrieved 9 December 2013.

- "New Maglev Shinkansen line to start from Shinagawa Station in Tokyo". Mainichi Daily News. 2008-07-03. Retrieved 2008-07-03.

- "LDP OKs maglev line selections". The Japan Times. 2008-10-21. Archived from the original on 2012-07-16. Retrieved 2008-10-21.

- "JR Tokai gives maglev estimates to LDP; in favor of shortest route". The Japan Times. 2009-06-19. Archived from the original on 2009-07-12. Retrieved 2009-07-08.

- "New maglev bullet train line to run through South Alps". The Mainichi Daily News. 2010-10-21. Archived from the original on 2010-10-24. Retrieved 2010-10-26.

- "JR Central's Chuo maglev project approved". International Railway Journal. 2014-10-31. Retrieved 2014-12-21.

- "JR Central starts construction on Chuo maglev". International Railway Journal. 2014-12-18. Retrieved 2014-12-21.

- "Planned start of maglev trains brings construction boom, concern in Nagoya". The Asahi Shimbun. 29 January 2014. Archived from the original on 4 January 2015. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- JR東海、リニア新幹線建設を全額自己負担 総事業費5.1兆円 Archived July 4, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, IB Times, December 26, 2007 (in Japanese)

- JR Tokai to build maglev system, The Japan Times, December 26, 2007

- "New maglev Shinkansen to run underground for 86% of initial route". The Asahi Shimbun. Archived from the original on 26 December 2014. Retrieved 11 February 2015.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-08-28. Retrieved 2015-08-29.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-01-30. Retrieved 2016-01-28.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "東名阪経済圏が誕生? リニア新幹線で日本変わるか". Nihon Keizai Shimbun. 4 January 2014. Retrieved 7 January 2014.

- "リニアでJR東海と対立、静岡県の「本当の狙い」 | 新幹線". 東洋経済オンライン (in Japanese). 2019-07-08. Retrieved 2019-09-22.

- "リニア開業遅れの懸念 愛知側「国が調整やらないかん」:朝日新聞デジタル". 朝日新聞デジタル (in Japanese). Retrieved 2019-09-23.

- Uno, Mamoru. "Chuo Shinkansen Project Using Superconducting Maglev System" (PDF). Japan Railway & Transport Review. Retrieved 5 March 2018.

- "Energy Consumption of Track-Based High-Speed Transportation Systems: Maglev Technologies in Comparison with Steel-Wheel-Rail". 2018.

- "鉄道を他交通機関と比較する" (PDF).

- "CS300 first flight Wednesday, direct challenge to 737-7 and A319neo". Leeham News and Analysis. 2015-02-25. Retrieved 2019-03-14.

- http://www.mlit.go.jp/common/000145486.pdf

- "Japan's maglev train breaks world speed record with 600km/h test run". The Guardian. United Kingdom: Guardian News and Media Limited. 21 April 2015. Retrieved 21 April 2015.