Colonia Buenos Aires

Colonia Buenos Aires is a colonia of the Cuauhtémoc borough located south of the historic center of Mexico City. This colonia is primarily known for its abundance of dealers selling used car parts, and an incident when six youths were executed by police. About half of the colonia’s residents make a living from car parts, but these businesses have a reputation for selling stolen merchandise. The colonia is also home to an old cemetery established by Maximilian I, which has a number of fine tombs and sculptures.

Buenos Aires | |

|---|---|

Dr. Andrade Street at the very north end of the colonia | |

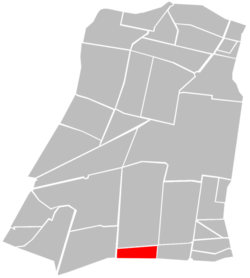

Location of Colonia Buenos Aires (in red) within Cuauhtémoc borough | |

| Country | Mexico |

| City | Mexico City |

| Borough | Cuauhtémoc |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 5,772[1] |

| Postal code | 06780 |

Location

The neighborhood is bordered by:[2]

- Eje 3 Sur Dr. Ignacio Morones Prieto on the north, across which is Colonia Doctores

- Eje 1 Poniente Cuauhtémoc on the west, across which is Colonia Roma Sur

- Viaducto Miguel Alemán on the south, across which is Colonia Piedad Narvarte and Colonia Atenor Salas

- Eje Central Lázaro Cárdenas on the east, across which is Colonia Algarín

History

While there are no records to establish an exact date, the colonia was probably first constructed at the beginning of the 20th century, beginning with irregular and unregulated housing around Hidalupe and El Tinado Streets. The first mention of it in official records is in the Boletín Municipal in 1920, which reports that 23 blocks and 285 residences were already in existence.[3] The Boletín also mentions that the area was not authorized for housing.[4] It is believed that the name is ironic, as at the time wastewater flowed past here in the Rio La Piedad.[3]

Originally, it was home to a large number of plumbers and those who sold tools. From in the 1940s, with the rise of the automobile, work associated with cars, such as mechanics and taxi drivers began to dominate the economy. This led to the selling of auto parts as the main business.[3][5]

In 1997, Buenos Aires became famous due to a tragedy that came to symbolize urban violence at that time, being widely reported and analyzed for weeks on radio and television.[5] The incident left the neighborhood with a violent reputation.[5] Six youths disappeared during a police operation on September 8, 1997 by “preventative police” squad of the Secretaria de Seguridad Publica. The sweep was in response to a recent shooting in which a policeman and a resident died.[6] The young men were apprehended by the police as they occupied an abandoned car in front of a city run child care center.[5] Of the six that disappeared, three were found dead in Tlahuac with evidence that they had been executed. The bodies assumed to be of the other three were found in a rural area of Ajusco.[6] The three found in Tlahuac had signs of torture and their faces disfigures beyond recognition.[7] The bodies were mutilated with only one remaining not decapitated.[8] One of the victims received 13 shots, 10 to the head.[8]

More than 400 government agents were investigated including police and some nearby military personnel. Thirty six were accused and 13 convicted.[6] The accused and convicted were mostly members of two elite police squads called the “Zorros” (Foxes) and the “Jaguares” (Jaguars).[7]

The bodies of three of the men were left with authorities because their families demanding DNA tests from abroad to verify identity.[6] Six years after their death, the remains of the three, Ángel Leal Alonso, Carlos Alberto López Inés and Román Morales, were still in the lockers of the Forensics Service. Due to bureaucratic paperwork, the families had not been able to retrieve them, and some had decided to leave them there.[8]

In 1998, the family received reparations from the city. The families demanded one million pesos for each victim but received 400,000. At the corner of Doctor Andrade and Ingeniero Bolaños Cacho an altar to the Virgin of Guadalupe serves as a memorial to the victims.[6]

The notoriety of the event prompted Conrado Tostado, the director of the Museum of the City of Mexico, to get the city to sponsor sculptures for Colonia Buenos Aires. One artist who did work here was Ivonne Domenge. These are sculptures are made of machine parts soldered together and located on the traffic islands on Doctor Vértiz Street.[5]

Another artist who became interesting in working in the colonia was Betsabeé Romero, whose specialty is in altars and commemorative works, with emphasis on symbolism. In 1995, she began to be interested in cars and their role in the urban landscape. She first created a piece using a 1955 Ford Crown Victoria in Tijuana, then began to be interested in Buenos Aires after the 1997 incident. She tried to work in the colonia, creating pieces, much as she did in Tijuana but area residents became suspicious of her activities. Early pieces were quickly vandalized. Romero then worked to introduce herself and her work to residents and workers in the area. This resulted in success, and the “adoption” of five long-abandoned cars on the streets of the colonia.[5]

One of these cars was “seeded” here by local police with the aim of accusing local shop owners of auto theft, thus rendering it “taboo” and “untouchable.”[5] This one was converted into a massive flowerpot with a large nopal cactus plant. Another was covered in antique tile. The most accepted was based on a 1979 Grand Marquis parked in front of the child care center where the executed youths had been taken. This car was “bandaged” and otherwise prepped to allow residents to cover it in graffiti, insults, messages and more.[5]

Description and population

The colonia is located south of the historic center of Mexico City. The borders are marked by the following streets: Viaducto Miguel Alemán to the south, Eje Tres Sur to the north, Eje Central to the east and Avenida Cuauhtémoc to the west.[4] Today, there are 256 established businesses There are 23 blocks with 1,685 housing units and 256 established businesses.[3]

It is a poor area, of about 5,000 people, about half of whom make a living from selling auto parts.[3] Most residents are between 15 and 30 years of age. Many of the children begin working at age 10 and abandon school.[8]

There is only one school, the Celerino Cano primary school, in which few students attend and there is a high dropout rate. There are no sports facilities, no cultural centers, parks or other public spaces. There are no offices for city social programs.[8]

Used auto parts

While there are 236 officially registered businesses in the colonia,[3] there are an estimated 400 businesses dedicated to the sale of used car parts alone.[9] These businesses have a reputation for selling parts from stolen cars.[9] One reason for this is that a boom in stolen parts began in the 1970s, when chrome accessories such as bumpers and mirrors began to be replaced by cheaper and interchangeable plastic parts.[3] The Unión de Comerciantes de Refacciones y Accessorios Nuevos y Usados para Autos y Camiones de la Colonia Buenos Aires says that this is not the case, that there exists a norm for the acquisition and sale of used auto parts.[3] The government, too, has ceased to consider the area as a major focus for the traffic in stolen auto parts but the reputation persists.[3][9] In the 2000s, there were efforts between the business association and the city government to help the used auto part market here but these talks fell through after then mayor Andrés Manuel López Obrador was told that the market here was primarily in stolen parts.[9]

The police are also accused of colluding with car thieves and chop shops in this area.[7] However, in April 2010, 35 tons of auto parts were confiscated in a sweep of the colonia. It was part of an ongoing investigation into seven car theft rings in the city and the state of Querétaro.[10]

Since the area is filled with small shops, there are as many as 235 people who work as “coyotes.” These people stand in the streets and look for potential customers as they enter the neighborhood. Then they work to help find the part from the various stores in their area. They also are supposed to help keep customers from the area from getting robbed, but they have been implicated in such crimes.[3]

Crime

The area has a reputation of being “bravo” (lit. fierce) or dangerous and a “nido de delincuentes” (nest of delinquents) even though crime statistics here are fairly low.[3] The government considers the area to be populated by generally honest people but infiltrated by delinquents.[3] Many state that it is perfectly safe to walk the streets in the center of the colonia, although they admit the area in the north that borders Colonia Doctores does have some problems with delinquents.[9] Most of the crime in the area (outside of the trafficking of stolen car parts) involves car theft, muggings and homicide.[8]

The more serious problem is the sale of drugs in the area. There have been 25 areas in the 27 block area identified as selling drugs. Many of the substances sold include very cheap ones, including inhalants, which primarily affect the young people of the colonia.[3] Another problem is the robbery of those from outside who enter the area, especially those who come to shop. This is one of the reasons the colonia has been ranked as one of the most dangerous in the Cuauhtémoc borough. Assaults tend to concentrate on the following streets: Doctor Norma, Federico Gomez Santos, Andrade as well as near the Centro Médico hospital.[3]

Panteón Francés de la Piedad

The neighborhood contains the Panteón Francés de la Piedad (French Cemetery of Piety) which was founded by Maximilian I in the 19th century.[4] Today, this cemetery is mostly abandoned and quiet, even on Day of the Dead, when most Mexican families visit family graves. Many are tombs over 100 years old, abandoned. Some remain works of art but others are totally destroyed. The grounds are not kept. The remains of Francisco I. Madero, José María Pino Suárez, Emilio Portes Gil, Javier Torres Adalid, Mariano Escobedo and José Revueltas are buried here.[11]

The cemetery was used mostly by the well-to-do and many of the graves have Art Nouveau designs. Those with the means would have large gravestones, small buildings and/or sculptures on the gravesites. Many of the sculptures refer to death, fragility and the brevity of life. Some were done by an Italian sculptor named Ponzanelli. There is also a 100-year-old replica of the Pietà sculpture by Michelangelo.[11] The government of the Cuauhtémoc borough states that the cemetery was closed in 1924;[4] however, Oaxacan writer Andrés Henestrosa was buried here in 2008, which was his wish according to his daughter.[12]

Transportation

Public transportation

The area is served by the Mexico City Metro. While it is not inside the neighborhood limits, Metro Lázaro Cárdenas is within walking distance.

Metro stations

References

- Delegación Cuauhtémoc. "Delegación Cuauhtémoc Entorno" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2018-06-12. Retrieved 2018-06-11.

- (in Spanish) Mapa de colonias de la Delegación Cuauhtémoc (Map of colonias of the Cuauhtémoc borough

- Luis Ramon Ocampo (July 7, 2002). "La Buenos Aires en el limbo" [Colonia Buenos Aires in limbo]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 2.

- "Colonia Buenos Aires" (in Spanish). Mexico City: Borough of Cuauhtémoc. Archived from the original on August 10, 2008. Retrieved August 17, 2010.

- Olivier Debroise (July 26, 2001). "La 'cosecha' de Romero en la Buenos Aires" [The "harvest" of Romero en Colonia Buenos Aires]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 4.

- Beatriz Vargas; Francisco Rodriguez (September 9, 1999). "Olvidan restos de tres victimas" [They forget the remains of three victims]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 1.

- Genoveva Caballero (April 1, 1998). "La mala vida en la colonia Buenos Aires". Contenido (in Spanish). Mexico City.

- Josefina Quintero Morales (September 8, 2003). "La Buenos Aires, entre el estigma y el olvido" [Colonia Buenos Aires, between stigma and oblivion]. SDP Noticias (in Spanish). Mexico City.

- Ricardo Zamora (October 5, 2001). "Culpan a la Doctores" [They blame Colonia Doctores]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 2.

- "Incautan 35 toneladas de autopartes en la colonia Buenos Aires" [Impound 35 tons of auto parts in Colonia Buenos Aires]. SDP Noticias (in Spanish). Mexico City. April 27, 2010. Archived from the original on May 1, 2010. Retrieved August 18, 2010.

- Marissa Rivera. "El Panteón Francés, monumento artístico en el olvido" [The Panteón Francés, an artistic monument in oblivion]. Televisa (in Spanish). Mexico City.

- "Sepultarán a Henestrosa en Panteón Francés" [Will bury Henestrosa in Panteón Francés]. Terra (in Spanish). Mexico City. January 11, 2008.