Thomas Nelson Page

Thomas Nelson Page (April 23, 1853 – November 1, 1922) was a lawyer and American writer.[1] He also served as the U.S. ambassador to Italy from 1913 to 1919 under the administration of President Woodrow Wilson during World War I. Page popularized the Southern tradition of the plantation genre as based on his own experience living in a plantation. Page first got the public's attention with his story “Marse Chan” which was published in the Century Illustrated Magazine. One of Page's most notable works include The Burial of the Guns and In Ole Virginia. [2][3] Page died in Oakland on November 1, 1922 aged 69.

Thomas Nelson Page | |

|---|---|

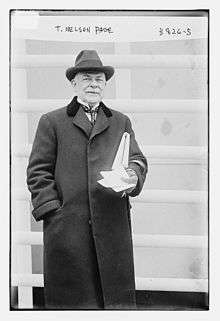

Portrait of Thomas Nelson Page, by Frances Benjamin Johnston | |

| Born | April 23, 1853 Virginia, U.S. |

| Died | November 1, 1922 (aged 69) Virginia, U.S. |

| Resting place | Rock Creek Cemetery, Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Spouse | Florence Lathrop Field |

| Signature |  |

Biography

Page was born in one of the Nelson family's plantations in Oakland, near the village of Beaverdam in Hanover County, Virginia. He was the son to John Page, a lawyer and a plantation owner, and Elizabeth Burwell (Nelson).[4] He was a scion of the prominent Nelson and Page families, each First Families of Virginia. Although he was from once-wealthy lineage, after the American Civil War, which began when he was only 8 years old, his parents and their relatives were largely impoverished during Reconstruction and his teenage years. In 1869, he entered Washington College, known now as Washington and Lee University, in Lexington, Virginia when Robert E. Lee was president of the college. In Page's later literary works, Robert E. Lee would come to serve as the model figure of Southern Heroism.[5] Page left Washington College before graduation for financial reasons after three years, but continued to desire an education specifically in law. To earn money to pay for his degree, Page tutored the children of his cousins in Kentucky. From 1873 to 1874, he was enrolled in the law school of the University of Virginia. At Washington College and thereafter at UVA, Nelson was a member of the prestigious fraternity Delta Psi, AKA St. Anthony Hall.

Admitted to the Virginia Bar Association, he practiced as a lawyer in Richmond between 1876 and 1893, and also began his writing career. He was married to Anne Seddon Bruce on July 28, 1886. She died on December 21, 1888 of a throat hemorrhage.

He remarried on June 6, 1893, to Florence Lathrop Field, a widowed sister-in-law of retailer Marshall Field. In the same year Page, who had become disillusioned with the Southern legal system, gave up his practice entirely and moved with his wife to Washington, D.C. There, he kept up his writing, which amounted to eighteen volumes when they were compiled and published in 1912. Page popularized the plantation tradition genre of Southern writing, which told of an idealized version of life before the Civil War, with contented slaves working for beloved masters and their families. He based much of his writing on his personal experience living on a plantation in the Antebellum South. Page viewed the Antebellum South as a representation of moral purity, and often vilified the reforms of the Gilded Age as a sign of moral decline.[6]

His 1887 collection of short stories, In Ole Virginia, is Page's quintessential work, providing a depiction of the Antebellum South. Criticism of Page's works runs the gamut, largely based upon whether the critic holds traditionalist or revisionist viewpoints of the antebellum South, War, and Reconstruction years. His most well-known short-story from that collection was "Marse Chan". "Marse Chan" was popularized because of Page's ability to capture southern dialect.[7] Another short-story collection of his is entitled The Burial of the Guns (1894).

As a result of his literary success, Page was popular amongst the Capital elite, and was regularly invited to socialize with politicians from around the country.[8] During the first quarter of the 20th century, he founded a library in the Sycamore Tavern structure near Montpelier, Virginia, in memory of his wife, Florence Lathrop Page.[9]

Under President Woodrow Wilson, Page was appointed as U.S. ambassador to Italy for six years between 1913 and 1919. There he supported the Czechoslovak Legion in Italy.[10] Despite being untrained in Italian and having little experience in governmental affairs, Page was determined to do a good job. He eventually learned Italian, formed beneficial relationships with Italian government officials, and accurately reported on the Italian state during World War I.[8] During his time as ambassador Page managed to maintain and improve American-Italian relations during World War I, and provided a sympathetic ear to the Italian and Triple Entente cause in the U.S government. After a disagreement with President Wilson over the terms of the Treaty of Versailles, in which he argued for increased Italian benefits, Page resigned his post in 1919. His book entitled Italy and the World War (1920) is a memoir of his service there.

After returning to his home in Oakland, Virginia, Page continued to write for the remainder of his years. He died in 1922 at Oakland, Virginia in Hanover County, Virginia.

Historical sites

Page was an activist in stimulating the Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities to mobilize to save historical sites at Yorktown and elsewhere, especially in the Historic Triangle of Virginia, from loss to development. He was involved in gaining Federal funding to build a seawall at Jamestown in 1900, protecting a site where the remains of James Fort were later discovered by archaeologists working on the Jamestown Rediscovery project which began in 1994.

Family

The Page and Nelson families were each among the First Families of Virginia. The Page lineage in Virginia began with the arrival at Jamestown of Colonel John Page at Jamestown in 1650. Col. Page was a prominent founder of Middle Plantation, which was later renamed Williamsburg. The Page family included Mann Page, U.S. Congressman and Governor John Page. The Nelson lineage began with Thomas "Scotch Tom" Nelson, a Scottish immigrant who settled at Yorktown, and his son, William Nelson, who was a royal governor of Virginia. Thomas Nelson Page was a direct descendant of Thomas Nelson, Jr., a signer of the Declaration of Independence and a governor after Statehood, and thus of Robert "King" Carter, who served as an acting royal governor of Virginia and was one of its wealthiest landowners in the late 17th and early 18th centuries. The Nelson family had settled in Hanover County, where Thomas's mother Elizabeth Burwell Nelson, married John Page.

A contemporary cousin of Thomas Nelson Page was William Nelson Page (1854–1932), who became a civil engineer and mining manager had helped develop the natural resources of western Virginia and southern West Virginia in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. William Page is credited with, in partnership with millionaire financier Henry Huttleston Rogers, planning and Building the Virginian Railway. His family's Victorian-era mansion, the Page-Vawter House in Ansted, West Virginia, is a National Historical Landmark as is a former company store of the Page Coal and Coke Company in Pageton.Other cousins were Confederate officers Robert Edward Lee and Richard Lucian Page

The ruins of Rosewell Plantation, the home of early members of the Page family and one of the finest mansions built in the colonies, sit on the banks of the York River in Gloucester County. In 1916, a fire swept the mansion leaving a magnificent shell which is testament to 18th century craftsmanship and dreams. There are ongoing archaeological studies at the site.

Writing themes

Thomas Nelson Page was one of the best-known writers of his day. He served as Woodrow Wilson's ambassador to Italy, and the president referred to him as a "national ornament".[11]

Page's postbellum fiction featured a nostalgic view of the South in step with what is termed Lost Cause ideology. Slaves are depicted as happy and simple, slotted into a paternalistic society. For example, the former slave in Marse Chan is uneducated, speaks phonetically, and has unrelenting admiration for his former master.[12] The gentry are noble and principled, with fealty to country and to chivalry—they seem like knights of a different age. The strain epitomized by Page would carry through the postwar era, cropping up again in art with films like Birth of a Nation. The ideology and thoughts that appear in Page's writing and in Southern ideology are no mere simplistic, archaic world-view; they are part of a complex history that has informed, for worse and for better, the evolution of the Southern mind to today.[13]

Thomas Nelson Page lamented that the slavery-era "good old darkies" had been replaced by the "new issue" (blacks born after slavery) whom he described as "lazy, thriftless, intemperate, insolent, dishonest, and without the most rudimentary elements of morality" (pp. 80, 163). Page, who helped popularize the images of cheerful and devoted Mammies and Sambos in his early books, became one of the first writers to introduce a literary black brute.

In 1898 he published Red Rock, a Reconstruction novel, with the heinous figure of Moses, a loathsome and sinister black politician. Moses tried to rape a white woman: "He gave a snarl of rage and sprang at her like a wild beast" (pp. 356–358). The depiction of rape using animal metaphors was a common feature of American sentimental literature.[14] He was later lynched for "a terrible crime".

Page dealt with the morality of lynching by acquitting the mob from any guilt, holding, instead, the supposedly debased Negroes responsible for their own violent executions. The following excerpts are taken from Page's essay, "The Negro: The Southerner's Problem," published in 1904. Page expected his reader to read his entire book with care before making judgments on complex, difficult subjects, in accordance with a society that read in depth. In his words in his introduction:

In this discussion, one thing must be borne in mind: In characterizing the Negroes generally, it is not meant to include the respectable element among them, except where this is plainly intended. Throughout the South there is such an element, an element not only respectable, but universally respected.[15]

With that in mind, Page's works include the following for which the disclaimer was necessary:

Lynching does not end ravishing, and that is the prime necessity... The charge that is often made, that the innocent are sometimes lynched, has little foundation. The rage of a mob is not directed against the innocent, but against the guilty; and its fury would not be satisfied with any other sacrifices than the death of the real criminal. Nor does the criminal merit any consideration, however terrible the punishment. The real injury is to the perpetrators of the crime of destroying the law, and to the community in which the law is slain...

The crime of lynching is not likely to cease until the crime of ravishing and murdering women and children is less frequent than it has been of late. And this crime, which is well-nigh wholly confined to the Negro race, will not greatly diminish until the Negroes themselves take it in hand and stamp it out...

As the crime of rape of late years had its baleful renascence in the teaching of equality and the placing of power in the ignorant Negroes' hands, so its perpetuation and increase have undoubtedly been due in large part to the same teaching. The intelligent Negro may understand what social equality truly means, but to the ignorant and brutal young Negro, it signifies but one thing: the opportunity to enjoy, equally with white men, the privilege of cohabiting with white women.[16]

Likewise, Thomas Nelson Page complained that African American leaders should cease "talk of social equality that inflames the ignorant Negro,"[17] and instead, work to stop "the crime of ravishing and murdering women and children."[17]

Publications

- In Ole Virginia, or Marse Chan and Other Stories (1887) short stories.

- Befo' de War: Echoes in Negro Dialect (1888) poems.

- Two Little Confederates (1888) short novel for young readers.

- Among the Camps (1891) short stories for young readers.

- Elsket, and Other Stories (1891) short stories.

- On Newfound River (1891) novel.

- The Old South: Essays Social and Political (1892) essays.

- The Burial of the Guns (1894) short stories and one novella.

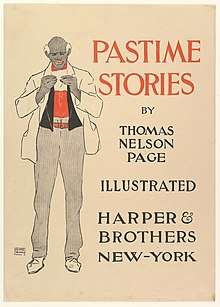

- Pastime Stories (1894) short stories.

- Unc' Edinburg: A Plantation Echo (1895).

- Social Life in Old Virginia Before the War (1896).

- The Old Gentleman of the Black Stock (1897) novella.

- Red Rock: A Chronicle of Reconstruction (1898) novel.

- Santa Claus's Partner (1899).

- A Captured Santa Claus (1900).

- Gordon Keith (1903) novel.

- Two Prisoners (1903).

- Bred in the Bone (1904) short stories.

- The Negro (1905).

- The Coast of Bohemia (1907) poems.

- John Marvel, Assistant (1907) novel.

- Under the Crust (1907) short stories and one play.

- The Old Dominion: Her Making and Her Manners (1908) essays.

- Tommy Trot's Visit to Santa Claus (1908).

- Robert E. Lee: The Southerner (1908).

- Mount Vernon and Its Preservation, 1858-1910 (1910).

- Robert E. Lee: Man and Soldier (1911).

- The Land of the Spirit (1913).

- The Page Story Book (1914).

- The Stranger's Pew (1914) short story.

- The Shepherd Who Watched by Night (1916).

- Address at the Three Hundredth Anniversary of the Settlement of Jamestown (1919).

- Italy and the World War (1920).

- Dante and His Influence: Studies (1922).

- The Red Riders (1924).

Selected articles

- "Lee in Defeat," The South Atlantic Quarterly, Vol. VI (1907).

- "The Spirit of a People Manifested in their Art," Art and Progress, Vol. II (1910).

- "Our Relation to Art," The American Magazine of Art, Vol. XIII (1922).

Collected works

- The Novels, Stories, Sketches and Poems of Thomas Nelson Page (18 vols., 1910–12).

See also

- Thomas Nelson Page House, listed on the National Register of Historic Places

References

- "PAGE, Thomas Nelson". The International Who's Who in the World. 1912. p. 829.

- "Thomas Nelson Page | American author". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- "Thomas Nelson Page". HarperCollins US. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- Kunitz, Stanley. (1938). American Authors 1600-1900. A Biographical Dictionary of American Literature. New York: H.W Wilson.

- Simms, L. Moody. "Thomas Nelson Page". American National Biography Online. Retrieved September 9, 2011.

- Gross, Theodore L. (1967). Thomas Nelson Page. New York: Twayne Publishers Inc. p. 18.

- Kunitz, Stanley. (1938). American Authors 1600-1900. A Biographical Dictionary of American Literature. New York: H.W Wilson.

- Dauer, Richard Paul. "Thomas Nelson Page, Diplomat" (MA, College of William and Mary, 1972)

- Virginia Historic Landmarks Commission staff (January 1974). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination: Sycamore Tavern" (PDF). Virginia Department of Historic Resources.

- PRECLÍK, Vratislav. Masaryk a legie (TGM and legions), váz. kniha, 219 str., vydalo nakladatelství Paris Karviná, Žižkova 2379 (734 01 Karviná) ve spolupráci s Masarykovým demokratickým hnutím (Masaryk democratic movement in Prague), 2019, ISBN 978-80-87173-47-3, page 19 - 25, 87

- Abbott, Shirley. Womenfolks, growing up down South. New Haven, Conn.: Ticknor & Fields, 1983. Print.

- Page, Thomas Nelson. Marse Chan excerpted from in Ole Virginia. Charles Scribner's Sons, 1887.

- Cash, W.J. Mind of the South. Vintage.

- Woodward, Vincent. The Delectable Negro: Human Consumption and Homoeroticism within US Slave Culture. NYU Press. p. 109.

- The Negro. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, pp. xi.

- Page, Thomas Nelson (1904). The Negro. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, pp. xi, 108, 109, 111, 112–113.

- Page (1904), p. 111.

Further reading

- Bailey, Fred Arthur (1997). "Thomas Nelson Page and the Patrician Cult of the Old South," International Social Science Review, Vol. 72, No. 3/4, pp. 110–121.

- Baskervill, William Malone (1911). "Thomas Nelson Page." In: Southern Writers. Nashville, Tenn.: Publishing House M.E. Church, South, pp. 120–151.

- Bundrick, Christopher (2008). "Return of the Repressed: Gothic and Romance in Thomas Nelson Page's Red Rock," South Central Review, Vol. 25, No. 2, pp. 63–79.

- Cable, George W. (1909). "Thomas Nelson Page, a Study in Reminiscence and Appreciation," Book News Monthly, Vol. 18, pp. 139–140.

- Christmann, James (2000). "Dialect's Double-Murder: Thomas Nelson Page's 'In Ole Virginia'," American Literary Realism, Vol. 32, No. 3, pp. 234–243.

- Coleman, Charles W. (1887). "The Recent Movement in Southern Literature," Harper's Magazine, Vol. 74, pp. 837–855.

- Flusche, Michael (1976). "Thomas Nelson Page: The Quandary of a Literary Gentleman," The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 84, No. 4, pp. 464–485.

- Gaines, Anne-Rosewell J. (1981). "Political Reward and Recognition: Woodrow Wilson Appoints Thomas Nelson Page Ambassador to Italy," The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 89, No. 3, pp. 328–340.

- Gordon, Armistead C. (1924). "Thomas Nelson Page (1853–1922)." In: Virginian Portraits. Staunton, Va.: McClure Company, pp. 125–137.

- Gross, Theodore L. (1966). "Thomas Nelson Page: Creator of a Virginia Classic," The Georgia Review, Vol. 20, No. 3, pp. 338–351.

- Holman, Harriet R. (1969). "Thomas Nelson Page's Account of Tennessee Hospitality," Tennessee Historical Quarterly, Vol. 28, No. 3, pp. 269–272.

- Holman, Harriet R. (1970). "The Kentucky Journal of Thomas Nelson Page," The Register of the Kentucky Historical Society, Vol. 68, No. 1, pp. 1–16.

- Holman, Harriet R. (1970). "Attempt and Failure: Thomas Nelson Page as Playwright," The Southern Literary Journal, Vol. 3, No. 1, pp. 72–82.

- Kent, Charles W. (1907). "Thomas Nelson Page," The South Atlantic Quarterly, Vol. 6, pp. 263–271.

- Martin, Matthew R. (1998). "The Two-Faced New South: The Plantation Tales of Thomas Nelson Page and Charles W. Chesnutt," The Southern Literary Journal, Vol. 30, No. 2, pp. 17–36.

- McCluskey, John (1982). "Americanisms in the Writings of Thomas Nelson Page," American Speech, Vol. 57, No. 1, pp. 44–47.

- Mims, Edwin (1907). "Thomas Nelson Page," The Atlantic Monthly, Vol. 100, pp. 109–115.

- Page, Rosewell (1923). Thomas Nelson Page. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons.

- Quisenberry, A.C. (1913). "The First Pioneer Families of Virginia", Register of the Kentucky State Historical Society, Vol. 11, No. 32, pp. 55, 57–77.

- Roberson, John R. (1956). "Two Virginia Novelists on Woman's Suffrage: An Exchange of Letters between Mary Johnston and Thomas Nelson Page," The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 64, No. 3, pp. 286–290.

- Wilson, Edmund (1962). Patriotic Gore: Studies in the Literature of the Civil War. New York: Oxford University Press.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Thomas Nelson Page. |

- Works by Thomas Nelson Page at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Thomas Nelson Page at Internet Archive

- Works by Thomas Nelson Page, at Hathi Trust

- Works by Thomas Nelson Page, at JSTOR

- Works by Thomas Nelson Page, at Unz.org

- Works by Thomas Nelson Page at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Social Life in Old Virginia before the War. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1897.

- Thomas Nelson Page on IMDb

- Thomas Nelson Page at Find a Grave

- Thomas Nelson Page, 1853–1922

- Thomas Nelson Page at Library of Congress Authorities, with 100 catalog records

| Diplomatic posts | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Thomas J. O'Brien |

United States Ambassador to Italy October 12, 1913 – June 21, 1919 |

Succeeded by Robert Underwood Johnson |