The Fenyeit Freir of Tungland

Ane Ballat of the Fenyeit Frier of Tungland, How He Fell in the Myre Fleand to Turkiland is a comic, satirical poem in Scots by William Dunbar (born 1459 or 1460) composed in the early sixteenth century. The title may be rendered in modern English as A Ballad of The False Friar of Tongland, How He Fell in the Mire Flying to Turkey.

The poem mocks an apparent attempt by John Damian, the abbott of Tongland, to fly from a wall of Stirling Castle using a pair of artificial wings. While pillorying this event, Dunbar makes a broader attack on Damian's character, depicting him as a habitual charlatan.[1][2][3]

The text of the poem is preserved in the Bannatyne Manuscript and, partially, in the Asloan Manuscript.[1]

Historical context

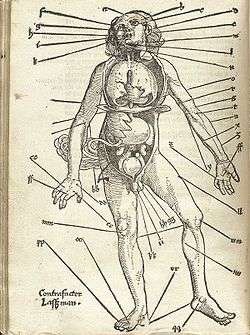

John Damian was an Italian-born cleric who came to Scotland, at the start of the sixteenth century and became a protégé of King James IV.[4] From 1501 he is recorded receiving payments from the King and is referred to as 'The French Leich' and 'The French Medicinar', suggesting that he practised medicine in some form.[4] He was made abbot of Tongland Abbey in Kirkcudbrightshire. His involvement with the natural sciences is confirmed by the alchemical experiments he carried out, at the King's expense, in Stirling in 1503.[4][5]

William Dunbar was a makar who was also close to James IV.[4] In his youth, he had accompanied diplomatic missions to France and England[5] and from 1500 was employed at the Royal court, often writing poetry which dealt with courtly events.[4] Dunbar's poem The Birth of Antichrist seems to be a second satire of John Damian with its reference to a flying abbot clothed in feathers.[1]

Damian's career was described by the later historian John Lesley.

- This tyme thair wes ane Italiane with the King, quha wes maid Abbott of Tungland, and wes of curious ingyne. He causet the King believe that he, be multiplyinge and utheris his inventions, wold make fyne golde of uther mettall, quhilk science he callit the Quintassence; quhairupon the King maid greit cost, bot all in vaine.[6]

Lesley records that, in 1507, Damian declared that he would travel to France by flight faster than a recently departed Scots embassy. He then leapt from a wall wearing his feathered costume and landed heavily, breaking a femur.

- This Abbott tuik in hand to flie with wingis and to be in Fraunce befoir the saidis ambassadours; and to that effectt he causet mak ane pair of wingis of fedderis, quhilks beand fessinit apoun him, he flew of the castell wall of Striveling, bot schortlie he fell to the ground and brak his thee bane.[6]

He then records that Damian explained his failure to achieve flight thus;

- the wyt thairof he asscryvit to that thair was some hen fedderis in the wingis quhilk yarnit for and covet the mydding and not the skyis.[6]

or, in English:

- he ascribed the blame to the fact that there were some hen feathers in the wings which yearn for and covet the midden and not the sky.[5]

Lesley compares Damian's exploit to a mythical King Bladud, but no further explanation for the Abbot's actions is given.[5]

The poem

The Fenyeit Freir of Tungland is composed in verse in the form of a Dream vision and forms a supposed biography of John Damian up to and including his attempt at flight. The tone of the poem is consistently humorous and scurrilous. Passages of fanciful fiction are mixed with elements of truth, albeit exaggerated for comic effect. In these respects it bears a strong resemblance in style to the contemporary literary form of flyting.[1]

Synopsis

The poem opens in formal, aureate style, with Dunbar declaring that, at dawn, he had a dream.

- As yung Aurora with cristall haile,

- In orient schew hir visage paile,

- A swevyng swyth did me assaile,[1]

The mood quickly becomes scurrilous. Although he will never be explicitly named, John Damian appears in the dream and is described as having Turkish origins,

- Me thocht a Turk of Tartary,

- Come throw the boundis of Barbary,

- And lay forloppin in Lumbardy,[1]

Damian is accused of having killed a cleric in Italy in order to acquire his habit and so impersonate him. This seems to be the origin of the epithet Feinyeit Freir.

- Thair a religious man he slew,

- And cled him in his abeit new,[1]

Damian is then supposed to have fled from Lombardy to France once his true identity was discovered. There, he pretended to be a physician, hiding his Italian origins.

- Quhen kend was his dissimulance,

- And all his cursit govirnance,

- For feir he fled and come in France,

- With littill of Lumbard leid.[1]

He is then accused of having no skill in bloodletting and being obliged to flee again.

- Vane organis he full clenely carvit,

- Quhen of his straik so mony starvit,

- Dreid he had gottin that he desarvit,

- He fled away gud speid.[1]

He arrives in Scotland, where he continues his medical malpractice.

- In leichecraft he was homecyd,

- He wald haif, for a nycht to byd,

- A haiknay and the hurt manis hyd,

- So meikle he was of mynace.

- His yrnis was rude as ony rawchtir.

- Quhair he leit blude it was no lawchtir.

- Full mony instrument for slawchtir,

- Was in his gardevyance.[1]

It is suggested that, after being appointed as an abbot, he neglected his religious duties in favour of alchemy.

- Unto no Mes pressit this prelat,

- For sound of sacring bell nor skellat,

- As blaksmyth bruikit was his pallatt,

- For battering at the study.[1]

After the failure of his alchemical work, he decides to fly back to Turkey with a coat of feathers. He takes off, observed by marvelling birds who compare him to mythical characters.

- Me thocht seir fassonis he assailyeit,

- To mak the quintessance, and failyeit,

- And quhen he saw that nocht availyeit,

- A fedrem on he tuke,

- And schupe in Turky for to fle.

- And quhen that he did mont on he,

- All fowill ferleit quhat he sowld be,

- That evir did on him luke.

- Sum held he had bene Dedalus,

- Sum the Menatair marvelus,

- Sum Martis blaksmyth, Vulcanus,

- And sum Saturnus kuke.[1]

The birds attack. During an extended descriptive passage, each species adopts a different tactic. They peck him, claw him, pluck his hair and tear at his wings.

- The tarsall gaif him tug for tug,

- A stanchell hang in ilka lug,

- The pyot furth his pennis did rug,

- The stork straik ay but stynt,

- The bissart, bissy but rebuik,

- Scho was so cleverus of hir cluik

- His bawis he micht not langer bruik,

- Scho held thame at ane hint.

- Thik was the clud of kayis and crawis,

- Of marleyonis, mittanis, and of mawis,

- That bikkrit at his berd with blawis,

- In battell him abowt.

- Thay nybbillit him with noyis and cry,

- The rerd of thame rais to the sky,

- And evir he cryit on Fortoun, "Fy!"

- His lyfe was into dowt.[1]

In a particularly scatological detail, the panic-stricken Damian loses control of his bowels above a herd of cattle,

- For feir uncunnandly he cawkit,

- Quhill all his pennis war drownd and drawkit,

- He maid a hundreth nolt all hawkit

- Beneth him with a spout.[1]

Deprived by the birds of his 'plumage', he falls into a midden, 'sliding up to the eyes in muck'.

- He schewre his feddreme that was schene,

- And slippit out of it full clene,

- And in a myre up to the ene.

- Amang the glar did glyd.[1]

Damian hides in the mud for three days while the carrion birds search for him.

- And he lay at the plunge evirmair,

- Sa lang as any ravin did rair.

- The crawis him socht with cryis of cair,

- In every schaw besyde.

- Had he reveild bene to the ruikis,

- Thay had him revin all with thair cluikis.

- Thre dayis in dub amang the dukis

- He did with dirt him hyde.[1]

Dunbar is then woken by the dawn chorus. To his frustration, his vision of Damian is 'taken with the tide'.

Interpretation

It is unclear how much of the poem is truthful and how much is exaggeration or fiction.

Certain episodes, such as the long and elaborate description of Damian's attack by a flock of outraged birds, are obvious fantasy.

Some of Dunbar's details are however corroborated by other documents. Principally, the Treasurer's accounts confirm that John Damian did indeed practice medicine and also dabbled in alchemy.[4] Bishop Lesley's history gives further corroboration.[6]

Dunbar's clear intention is to mock his target by any means available and so the reader must be the final judge of what is true and false in the poem.

References

- W. Mackay Mackenzie, The Poems of William Dunbar, The Mercat press, 1990.

- The full text with notes at TEAMS Archived 2007-03-14 at the Wayback Machine

- Womald, Jenny (1981). Court, Kirk and Community. Scotland 1470-1625, The New History of Scotland. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Accounts of the Lord High Treasurer of Scotland

- Nicolson, Ranald (1974). The Edinburgh History of Scotland Volume 2, 'The Later Middle Ages'. Edinburgh: Mercat Press.

- Lesley, John (1830). The History of Scotland: From the Death of King James I., in the Year 1436, to the Year 1561. Edinburgh, Scotland: Bannatyne Club.