Flyting

Flyting or fliting is a contest consisting of the exchange of insults between two parties, often conducted in verse.[1]

Etymology

The word flyting comes from the Old English verb flītan meaning 'to quarrel', made into a noun with the suffix -ing. Attested from around 1200 in the general sense of a verbal quarrel, it is first found as a technical literary term in Scotland in the sixteenth century.[2] The Dictionary of the Older Scottish Tongue gives the first attestation in this sense as The Flyting of Dumbar and Kennedie,[3] from around 1500.[4]

Description

it was with thy sister

thou hadst such a son

hardly worse than thyself.

Royatouslie, lyke ane rude rubatour

Ay fukkand lyke ane furious fornicatour

Sir David Lyndsay, An Answer quhilk Schir David Lyndsay maid Y Kingis Flyting (The Answer Which Sir David Lyndsay made to the King's Flyting), 1536.

Thersites: The plague of Greece upon thee, thou mongrel beef-witted lord!

William Shakespeare, Troilus and Cressida, Act 2, Scene 1.

Flyting is a ritual, poetic exchange of insults practised mainly between the 5th and 16th centuries. Examples of flyting are found throughout Norse, Celtic,[5] Old English and Middle English literature involving both historical and mythological figures. The exchanges would become extremely provocative, often involving accusations of cowardice or sexual perversion.

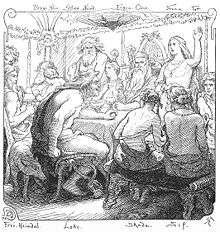

Norse literature contains stories of the gods flyting. For example, in Lokasenna the god Loki insults the other gods in the hall of Ægir. In the poem Hárbarðsljóð, Hárbarðr (generally considered to be Odin in disguise) engages in flyting with Thor.[6]

In the confrontation of Beowulf and Unferð in the poem Beowulf, flytings were used as either a prelude to battle or as a form of combat in their own right.[7]

In Anglo-Saxon England, flyting would take place in a feasting hall. The winner would be decided by the reactions of those watching the exchange. The winner would drink a large cup of beer or mead in victory, then invite the loser to drink as well.[8]

The 13th century poem The Owl and the Nightingale and Geoffrey Chaucer's Parlement of Foules contain elements of flyting.

Flyting became public entertainment in Scotland in the 15th and 16th centuries, when makars would engage in verbal contests of provocative, often sexual and scatological but highly poetic abuse. Flyting was permitted despite the fact that the penalty for profanities in public was a fine of 20 shillings (over £300 in 2020 prices) for a lord, or a whipping for a servant.[9] James IV and James V encouraged "court flyting" between poets for their entertainment and occasionally engaged with them. The Flyting of Dumbar and Kennedie records a contest between William Dunbar and Walter Kennedy in front of James IV, which includes the earliest recorded use of the word shit as a personal insult.[9] In 1536 the poet Sir David Lyndsay composed a ribald 60-line flyte to James V after the King demanded a response to a flyte.

Flytings appear in several of William Shakespeare's plays. Margaret Galway analysed 13 comic flytings and several other ritual exchanges in the tragedies.[10] Flytings also appear in Nicholas Udall's Ralph Roister Doister and John Still's Gammer Gurton's Needle from the same era.

While flyting died out in Scottish writing after the Middle Ages, it continued for writers of Celtic background. Robert Burns parodied flyting in his poem, "To a Louse," and James Joyce's poem "The Holy Office" is a curse upon society by a bard.[11] Joyce played with the traditional two-character exchange by making one of the characters society as a whole.

Similar practices

Hilary Mackie has detected in the Iliad a consistent differentiation between representations in Greek of Achaean and Trojan speech,[17] where Achaeans repeatedly engage in public, ritualized abuse: "Achaeans are proficient at blame, while Trojans perform praise poetry."[18]

Taunting songs are present in the Inuit culture, among many others. Flyting can also be found in Arabic poetry in a popular form called naqā’iḍ, as well as the competitive verses of Japanese Haikai.

Echoes of the genre continue into modern poetry. Hugh MacDiarmid's poem A Drunk Man Looks at the Thistle, for example, has many passages of flyting in which the poet's opponent is, in effect, the rest of humanity.

Flyting is similar in both form and function to the modern practice of freestyle battles between rappers and the historic practice of the Dozens, a verbal-combat game representing a synthesis of flyting and its Early Modern English descendants with comparable African verbal-combat games such as Ikocha Nkocha.[19]

In Finnic Kalevala the hero Väinämöinen uses similar practice of kilpalaulanta (duel singing) to win opposing Joukahainen.

Modern portrayals

In "The Roaring Trumpet", part of Harold Shea's introduction to the Norse gods is a flyting between Heimdall and Loki in which Heimdall utters the immortal line "All insults are untrue. I state facts."

The climactic scene in Rick Riordan's novel The Ship of the Dead consists of a flyting between the protagonist Magnus Chase and the Norse god Loki.

Recreation

In a May 2010 episode of the Channel 4 series Time Team, archaeologists Matt Williams and Phil Harding engage in some mock flyting in Old English written by Saxon historian Sam Newton to demonstrate the practice. For example, "Mattaeus, ic þé onsecge þæt þín scofl is nú unscearp æfter géara ungebótes" ("Matthew, I to thee say that thy shovel is now blunt after years of misuse").

See also

- Beot

- Senna

- Slam poetry

- The Dozens

- Maternal insult

- Battle rap

Notes

- Parks, Ward. "Flyting, Sounding, Debate: Three Verbal Contest Genres", Poetics Today 7.3, Poetics of Fiction (1986:439-458) provided some variable in the verbal contest, to provide a basis for differentiating the genres of flyting, sounding, and debate.

- "fliting | flyting, n.", OED Online, 1st edn (Oxford: Oxford University Press), accessed 1 April 2020.

- Dictionary of the Older Scottish Tongue, 12 vols (Chicago: University of Chicago Press; Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1931–2002), s.v. flyting.

- The Poems of William Dunbar, ed. by James Kinsley (Oxford University Press, 1979) ISBN 9780198118886, note to text 23.

- Sayers, William (1991). "Serial Defamation in Two Medieval Tales: The Icelandic Ölkofra Þáttr and The Irish Scéla Mucce Meic Dathó" (PDF). Oral Tradition. pp. 35–57. Retrieved 2016-03-16.

- Byock, Jesse (1983) [1982]. Feud in the Icelandic Saga. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-08259-1.

- Clover, Carol (1980). "The Germanic Context of the Unferth Episode", Spoeculum 55 pp. 444-468.

- Quaestio: selected proceedings of the Cambridge Colloquium in Anglo-Saxon, Norse, and Celtic Volumes 2-3, p43-44, University of Cambridge, 2001.

- An encyclopedia of swearing: the social history of oaths, profanity, foul language, and ethnic slurs in the English-speaking world, Geoffrey Hughes, M.E. Sharpe, 2006, p175

- Margaret Galway, Flyting in Shakespeare's Comedies, The Shakespeare Association Bulletin, vol. 10, 1935, pp. 183-91.

- "flyting." Merriam Webster's Encyclopedia of Literature. Springfield, MA: Merriam-Webster, 1995. Literature Resource Center. Web. 1 Oct. 2015.

- Oberman, Heiko Augustinus (1 January 1994). "The Impact of the Reformation: Essays". Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing – via Google Books.

- Luther's Last Battles: Politics And Polemics 1531-46 By Mark U. Edwards, Jr. Fortress Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0-8006-3735-4

- In Latin, the title reads "Hic oscula pedibus papae figuntur"

- "Nicht Bapst: nicht schreck uns mit deim ban, Und sey nicht so zorniger man. Wir thun sonst ein gegen wehre, Und zeigen dirs Bel vedere"

- Mark U. Edwards, Jr., Luther's Last Battles: Politics And Polemics 1531-46 (2004), p. 199

- Mackie, Hilary Susan (1996). Talking Trojan: Speech and Community in the Iliad. Lanham MD: Rowmann & Littlefield. ISBN 0-8476-8254-4., reviewed by Joshua T. Katz in Language 74.2 (1998) pp. 408-09.

- Mackie 1996:83.

- Johnson, Simon (2008-12-28). "Rap music originated in medieval Scottish pubs, claims American professor". telegraph.co.uk. Telegraph Media Group. Retrieved 2008-12-30.

Professor Ferenc Szasz argued that so-called rap battles, where two or more performers trade elaborate insults, derive from the ancient Caledonian art of "flyting." According to the theory, Scottish slave owners took the tradition with them to the United States, where it was adopted and developed by slaves, emerging many years later as rap; see also John Dollard, "The Dozens: the dialect of insult", American Image 1 (1939), pp 3-24; Roger D. Abrahams, "Playing the dozens", Journal of American Folklore 75 (1962), pp 209-18.

External links

- Flyting – britannica.com