Terrestrial planet

A terrestrial planet, telluric planet, or rocky planet is a planet that is composed primarily of silicate rocks or metals. Within the Solar System, the terrestrial planets are the inner planets closest to the Sun, i.e. Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars. The terms "terrestrial planet" and "telluric planet" are derived from Latin words for Earth (Terra and Tellus), as these planets are, in terms of structure, Earth-like. These planets are located between the Sun and the asteroid belt.

Terrestrial planets have a solid planetary surface, making them substantially different from the larger gaseous planets, which are composed mostly of some combination of hydrogen, helium, and water existing in various physical states.

Structure

All terrestrial planets in the Solar System have the same basic type of structure, such as a central metallic core, mostly iron, with a surrounding silicate mantle. The Moon is similar, but has a much smaller iron core. Io and Europa are also satellites that have internal structures similar to that of terrestrial planets. Terrestrial planets can have canyons, craters, mountains, volcanoes, and other surface structures, depending on the presence of water and tectonic activity. Terrestrial planets have secondary atmospheres, generated through volcanism or comet impacts, in contrast to the giant planets, whose atmospheres are primary, captured directly from the original solar nebula.[1]

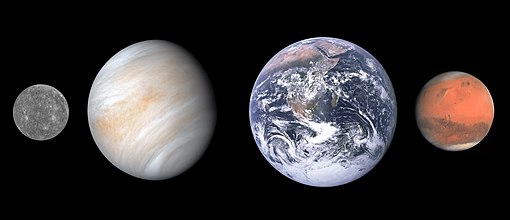

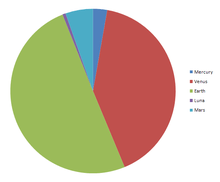

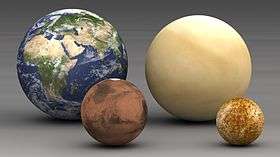

Solar System's terrestrial planets

The Solar System has four terrestrial planets: Mercury, Venus, Earth and Mars. Only one terrestrial planet, Earth, is known to have an active hydrosphere.

During the formation of the Solar System, there were probably many more terrestrial planetesimals, but most merged with or were ejected by the four terrestrial planets.

Dwarf planets, such as Ceres, Pluto and Eris, and small Solar System bodies are similar to terrestrial planets in the fact that they do have a solid surface, but are, on average, composed of more icy materials (Ceres, Pluto and Eris have densities of 2.17, 1.87 and 2.52 g·cm−3, respectively, and Haumea's , Makemake's and Gonggong's density is 2.02, 1.98 and 1.75 respectively g·cm−3). The Earth's Moon has a density of 3.4 g·cm−3 and Jupiter's satellites, Io, 3.528 and Europa, 3.013 g·cm−3; other satellites typically have densities less than 2 g·cm−3.[2][3]

Density trends

The uncompressed density of a terrestrial planet is the average density its materials would have at zero pressure. A greater uncompressed density indicates greater metal content. Uncompressed density differs from the true average density (also often called "bulk" density) because compression within planet cores increases their density; the average density depends on planet size, temperature distribution and material stiffness as well as composition.

| Object | Density (g·cm−3) | Semi-major axis (AU) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Uncompressed | ||

| Mercury | 5.4 | 5.3 | 0.39 |

| Venus | 5.2 | 4.4 | 0.72 |

| Earth | 5.5 | 4.4 | 1.0 |

| Mars | 3.9 | 3.8 | 1.52 |

The uncompressed density of terrestrial planets trends towards lower values as the distance from the Sun increases. The rocky minor planet Vesta orbiting outside of Mars is less dense than Mars still at, 3.4 g·cm−3.

Calculations to estimate uncompressed density inherently require a model of the planet's structure. Where there have been landers or multiple orbiting spacecraft, these models are constrained by seismological data and also moment of inertia data derived from the spacecraft orbits. Where such data is not available, uncertainties are inevitably higher.[4] It is unknown whether extrasolar terrestrial planets in general will show to follow this trend.

Extrasolar terrestrial planets

Most of the planets discovered outside the Solar System are giant planets, because they are more easily detectable.[5][6][7] But since 2005, hundreds of potentially terrestrial extrasolar planets have been found, with several being confirmed as terrestrial. Most of these are super-Earths, i.e. planets with masses between Earth's and Neptune's; super-Earths may be gas planets or terrestrial, depending on their mass and other parameters.

During the early 1990s, the first extrasolar planets were discovered orbiting the pulsar PSR B1257+12, with masses of 0.02, 4.3, and 3.9 times that of Earth's, by pulsar timing.

When 51 Pegasi b, the first planet found around a star still undergoing fusion, was discovered, many astronomers assumed it to be a gigantic terrestrial, because it was assumed no gas giant could exist as close to its star (0.052 AU) as 51 Pegasi b did. It was later found to be a gas giant.

In 2005, the first planets orbiting a main-sequence star and which show signs of being terrestrial planets, were found: Gliese 876 d and OGLE-2005-BLG-390Lb. Gliese 876 d orbits the red dwarf Gliese 876, 15 light years from Earth, and has a mass seven to nine times that of Earth and an orbital period of just two Earth days. OGLE-2005-BLG-390Lb has about 5.5 times the mass of Earth, orbits a star about 21,000 light years away in the constellation Scorpius. From 2007 to 2010, three (possibly four) potential terrestrial planets were found orbiting within the Gliese 581 planetary system. The smallest, Gliese 581e, is only about 1.9 Earth masses,[8] but orbits very close to the star. An ideal terrestrial planet would be two Earth masses, with a 25-day orbital period around a red dwarf.[9] Two others, Gliese 581c and Gliese 581d, as well as a disputed planet, Gliese 581g, are more-massive super-Earths orbiting in or close to the habitable zone of the star, so they could potentially be habitable, with Earth-like temperatures.

Another possibly terrestrial planet, HD 85512 b, was discovered in 2011; it has at least 3.6 times the mass of Earth.[10] The radius and composition of all these planets are unknown.

The first confirmed terrestrial exoplanet, Kepler-10b, was found in 2011 by the Kepler Mission, specifically designed to discover Earth-size planets around other stars using the transit method.[11]

In the same year, the Kepler Space Observatory Mission team released a list of 1235 extrasolar planet candidates, including six that are "Earth-size" or "super-Earth-size" (i.e. they have a radius less than 2 Earth radii)[12] and in the habitable zone of their star.[13] Since then, Kepler has discovered hundreds of planets ranging from Moon-sized to super-Earths, with many more candidates in this size range (see image).

List of terrestrial exoplanets

The following exoplanets have a density of at least 5 g/cm3 and a mass below Neptune's and are thus very likely terrestrial:

Kepler-10b, Kepler-20b, Kepler-36b, Kepler-48d, Kepler 68c, Kepler-78b, Kepler-89b, Kepler-93b, Kepler-97b, Kepler-99b, Kepler-100b, Kepler-101c, Kepler-102b, Kepler-102d, Kepler-113b, Kepler-131b, Kepler-131c, Kepler-138c, Kepler-406b, Kepler-406c, Kepler-409b.

The Neptune-mass planet Kepler-10c also has a density >5 g/cm3 and is thus very likely terrestrial.

Frequency

In 2013, astronomers reported, based on Kepler space mission data, that there could be as many as 40 billion Earth- and super-Earth-sized planets orbiting in the habitable zones of Sun-like stars and red dwarfs within the Milky Way.[14][15][16] 11 billion of these estimated planets may be orbiting Sun-like stars.[17] The nearest such planet may be 12 light-years away, according to the scientists.[14][15] However, this does not give estimates for the number of extrasolar terrestrial planets, because there are planets as small as Earth that have been shown to be gas planets (see KOI-314c).[18]

Types

Several possible classifications for terrestrial planets have been proposed:[19]

- Silicate planet

- The standard type of terrestrial planet seen in the Solar System, made primarily of silicon-based rocky mantle with a metallic (iron) core.

- Carbon planet (also called "diamond planet")

- A theoretical class of planets, composed of a metal core surrounded by primarily carbon-based minerals. They may be considered a type of terrestrial planet if the metal content dominates. The Solar System contains no carbon planets, but does have carbonaceous asteroids.

- Iron planet

- A theoretical type of terrestrial planet that consists almost entirely of iron and therefore has a greater density and a smaller radius than other terrestrial planets of comparable mass. Mercury in the Solar System has a metallic core equal to 60–70% of its planetary mass. Iron planets are thought to form in the high-temperature regions close to a star, like Mercury, and if the protoplanetary disk is rich in iron.

- Coreless planet

- A theoretical type of terrestrial planet that consists of silicate rock but has no metallic core, i.e. the opposite of an iron planet. Although the Solar System contains no coreless planets, chondrite asteroids and meteorites are common in the Solar System. Coreless planets are thought to form farther from the star where volatile oxidizing material is more common.

See also

References

- Dr. James Schombert (2004). "Primary Atmospheres (Astronomy 121: Lecture 14 Terrestrial Planet Atmospheres)". Department of Physics University of Oregon. Archived from the original on 13 July 2011. Retrieved 22 December 2009.

- NASA: Moons of Jupiter

- Space: The Earth's Moon density

- "Course materials on "mass-radius relationships" in planetary formation" (PDF). caltech.edu. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 December 2017. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- Carole Haswell, Transiting Exoplanets Archived 7 November 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- Michael Perryman, The Exoplanet Handbook Archived 7 November 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- Sara Seager, Exoplanets Archived 7 November 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- "Lightest exoplanet yet discovered". ESO (ESO 15/09 – Science Release). 21 April 2009. Archived from the original on 5 July 2009. Retrieved 15 July 2009.

- M. Mayor; X. Bonfils; T. Forveille; X. Delfosse; S. Udry; J.-L. Bertaux; H. Beust; F. Bouchy; C. Lovis; F. Pepe; C. Perrier; D. Queloz; N. C. Santos (2009). "The HARPS search for southern extra-solar planets,XVIII. An Earth-mass planet in the GJ 581 planetary system". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 507 (1): 487–494. arXiv:0906.2780. Bibcode:2009A&A...507..487M. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/200912172.

- Kaufman, Rachel (30 August 2011). "New Planet May Be Among Most Earthlike – Weather Permitting, Alien world could host liquid water if it has 50 percent cloud cover, study says". National Geographic News. Archived from the original on 23 September 2011. Retrieved 5 September 2011.

- Rincon, Paul (22 March 2012). "Thousand-year wait for Titan rain". Archived from the original on 25 December 2017 – via www.bbc.com.

- Namely: KOI 326.01 [Rp=0.85], KOI 701.03 [Rp=1.73], KOI 268.01 [Rp=1.75], KOI 1026.01 [Rp=1.77], KOI 854.01 [Rp=1.91], KOI 70.03 [Rp=1.96] – Table 6). A more recent study found that one of these candidates (KOI 326.01) is in fact much larger and hotter than first reported. Grant, Andrew (8 March 2011). "Exclusive: "Most Earth-Like" Exoplanet Gets Major Demotion—It Isn't Habitable". 80beats. Discover Magazine. Archived from the original on 9 March 2011. Retrieved 9 March 2011. External link in

|work=(help) - Borucki, William J; et al. (2011). "Characteristics of planetary candidates observed by Kepler, II: Analysis of the first four months of data". The Astrophysical Journal. 736 (1): 19. arXiv:1102.0541. Bibcode:2011ApJ...736...19B. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/736/1/19.

- Overbye, Dennis (4 November 2013). "Far-Off Planets Like the Earth Dot the Galaxy". New York Times. Archived from the original on 5 November 2013. Retrieved 5 November 2013.

- Petigura, Eric A.; Howard, Andrew W.; Marcy, Geoffrey W. (31 October 2013). "Prevalence of Earth-size planets orbiting Sun-like stars". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 110 (48): 19273–19278. arXiv:1311.6806. Bibcode:2013PNAS..11019273P. doi:10.1073/pnas.1319909110. PMC 3845182. PMID 24191033. Archived from the original on 9 November 2013. Retrieved 5 November 2013.

- Staff (7 January 2013). "17 Billion Earth-Size Alien Planets Inhabit Milky Way". Space.com. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 8 January 2013.

- Khan, Amina (4 November 2013). "Milky Way may host billions of Earth-size planets". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 6 November 2013. Retrieved 5 November 2013.

- "Newfound Planet is Earth-mass But Gassy". harvard.edu. 3 January 2014. Archived from the original on 28 October 2017. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- Naeye, Bob (24 September 2007). "Scientists Model a Cornucopia of Earth-sized Planets". NASA, Goddard Space Flight Center. Archived from the original on 24 January 2012. Retrieved 23 October 2013.