South Wales Valleys

The South Wales Valleys (Welsh: Cymoedd De Cymru) are a group of industrialised peri-urban valleys in South Wales. Most of the valleys run north–south, roughly parallel to each other. Commonly referred to as "The Valleys" (Welsh: Y Cymoedd), they stretch from eastern Carmarthenshire to western Monmouthshire; to the edge of the pastoral country of the Vale of Glamorgan and the coastal plain near the cities of Swansea, Cardiff, and Newport.

History

Until the mid-19th century, the South Wales valleys were sparsely inhabited. The industrialisation of the Valleys occurred in two phases. First, in the second half of the 18th century, the iron industry was established on the northern edge of the Valleys, mainly by English entrepreneurs. This made South Wales the most important part of Britain for ironmaking until the middle of the 19th century. Second, from 1850 until the outbreak of the First World War, the South Wales Coalfield was developed to supply steam coal and anthracite.[1]

The South Wales Valleys hosted Britain's only mountainous coalfields.[2] Topography defined the shape of the mining communities, with a "hand and fingers" pattern of urban development.[3] There were fewer than 1,000 people in the Rhondda valley in 1851, 17,000 by 1870, 114,000 by 1901 and 153,000 by 1911; but the wider impact of urbanisation was constrained by geography—the Rhondda remained a collection of villages rather than a town.[4] The population of the Valleys in the late 19th and early 20th centuries was disproportionately young and male; many of them were migrants drawn from other parts of Wales or from further afield.[4] The new communities had extremely high birth rates—in 1840, more than 20 per cent of Tredegar's population was aged under seven, and Rhondda's birth rate in 1911 was 36 per thousand, levels usually associated with mid-19th century Britain.[4]

Merthyr Tydfil, at the northern end of the Taff valley, became Wales's largest town thanks to its growing ironworks at Dowlais and Cyfarthfa. The neighbouring Taff Bargoed Valley to the east became the centre of serious industrial and political strife during the 1930s, especially in and around the villages of Trelewis and Bedlinog, which served the local collieries of Deep Navigation and Taff Merthyr. The South Wales coalfield attracted huge numbers of people from rural areas to the valleys; and many rows of terraced housing were built along the valley sides to accommodate the influx. The coal mined in the valleys was transported south along railways and canals to Cardiff, Newport and Swansea. Cardiff was soon among the most important coal ports in the world, and Swansea among the most important steel ports.

Decline

The coal mining industry of the Valleys was buoyed throughout World War II, though there were expectations of a return to the pre-1939 industrial collapse after the end of the war. There was a sense of salvation when the government announced the nationalisation of British coalmines in 1947; but the following decades saw a continual reduction in the output from the Welsh mines. The decline in the mining of coal after World War II was a country-wide issue, but southern Wales was more severely affected than other areas of Britain. Oil had superseded coal as the fuel of choice in many industries, and there was political pressure influencing the supply of oil.[5] Of the few industries that still relied on coal, the demand was for quality coals, especially coking coal, which was required by the steel industry. Fifty percent of Glamorgan coal was now supplied to steelworks,[6] with the second biggest market being domestic heating, in which the "smokeless" coal of the southern Wales coalfield again became fashionable after the Clean Air Act of 1956 was passed.[7] These two markets now controlled the fate of the mines in Wales, and as demand from both sectors fell, the mining industry contracted further. In addition exports to other areas of Europe, traditionally France, Italy and the Low Countries, experienced a massive decline: from 33% around 1900 to roughly 5% by 1980.[7]

The other major factor in the decline of coal was the massive under-investment in Welsh mines over the past decades. Most of the mines in the valleys were sunk between the 1850s and 1880s, so they were far smaller than most modern mines.[8] The Welsh mines were comparatively antiquated, with methods of ventilation, coal-preparation and power supply all of a decades-earlier standard.[8] In 1945 the British coal industry as a whole cut 72% of its output mechanically, whereas in the south of Wales the figure was just 22%.[8] The only way to ensure the financial survival of the mines in the valleys was massive investment from the National Coal Board, but the "Plan for Coal" drawn up in 1950 was overly optimistic about the future demand for coal,[9] which was drastically reduced following an industrial recession in 1956 and an increased availability of oil.[5] From 15,000 miners in 1947, Rhondda had just a single pit within the valleys producing coal in 1984, located at Maerdy.[10]

In 1966, the village of Aberfan in the Taff valley suffered one of the worst disasters in Welsh history, referred to today as the Aberfan disaster. A mine waste tip on the top of the mountain, which had been developed over a spring,[11] slid down the valley side and destroyed the village junior school, killing 144 people, 116 of them children.[12]

In 1979, Margaret Thatcher became Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. Her policies of free market economics soon clashed with the loss-making, government-owned National Coal Board. In 1984 and 1985, after the government announced plans to close many mines across the UK, mineworkers went on strike. This strike, and its ultimate failure, led to the virtual destruction of the UK's coal industry over the next decade, although arguably costs of extraction and geological difficulties would have had the same result, perhaps a little later. No deep coal mines are left in the valleys since the closure in 2008 of Tower Colliery in the Cynon Valley. Tower had been bought by the workers in 1994, despite government attempts to close it.

By 2002, the unemployment rates in the Welsh valleys were among the highest in the whole United Kingdom since the 1980s, and have been seen as a major factor in the rise in drug abuse in the local area, which was highlighted in the national media during the autumn of 2002 and largely linked to drug dealing gangs from Birmingham and Bristol.[13]

Present day

The Valleys are home to around 30% of the Welsh population, although this is declining slowly because of emigration, especially from the Upper Valleys.[14] The area is less diverse than the rest of the country, with a relatively high proportion of residents (over 90% in Blaenau Gwent and Merthyr Tydfil) born in Wales.[15] High rates of teenage pregnancy give the area a slightly younger age profile than Wales as a whole.[14]

The Valleys suffer from a number of socio-economic problems. Educational attainment in the Valleys is low, with a large proportion of people possessing few or no qualifications.[14] A high proportion of people report a limiting long-term health problem, especially in the Upper Valleys.[14] In 2006, only 64% of the working age population in the Heads of the Valleys was in employment compared with 69% in the Lower Valleys and 71% across Wales as a whole.[16]

A relatively large number of local people are employed in manufacturing, health and social services. Fewer work in managerial or professional occupations, and more in elementary occupations, compared to the rest of the country.[14] A large number of people commute to Cardiff, particularly in Caerphilly, Torfaen and Rhondda Cynon Taf. Though the rail network into Cardiff is extensive, train times and frequencies beyond Caerphilly and Pontypridd impede the development of a significant commuter market to city centre jobs.[14]

Although the housing stock is not of significantly worse quality than elsewhere in Wales, there is a lack of variety in terms of private dwellings.[16] Many homes are low-priced, older and terraced, concentrated in the lowest Council Tax bands; few are higher-priced detached homes.[14] A report for the Welsh Government concluded that the Valleys is "a distressed area unique in Great Britain for the depth and concentration of its problems".[14] However, the area does benefit from a local landscape described as "stunning", improving road links such as the upgraded A465, and public investment in regeneration initiatives.[16]

Following devolution in the late 2000s, powers over the Wales and Borders rail franchise are now held by the Welsh Government. As a result, financing has been advanced through the Cardiff City Deal for a South Wales Metro. The metro will consist of route electrification, new Construcciones y Auxiliar de Ferrocarriles trains manufactured at Llanwern for use in 2023, new stations, more frequent services, and faster journey times across most valleys. The first major improvement is the re-opening of services between Ebbw Vale and Newport (via the Gaer Tunnel) which is projected to be completed by 2021.[17]

Culture

The South Wales Valleys contain a large proportion of the Welsh population and remain an important centre of Welsh culture, despite the growing economic dominance of Cardiff. The UK Parliament's first Labour Party MP, Keir Hardie, was elected from the area, and the Valleys remain a stronghold of Labour Party power. Rugby union is very popular, and pitches can be seen along the valley corridors.

The geographical shape of the valleys has its effect on culture. Roads stretch along valleys and connect the different settlements in the valley, whereas neighbouring valleys are separated by hills and mountains. Consequently, the towns in a valley are more closely associated with each other than they are with towns in the neighbouring valley, even when the towns in the neighbouring valley are closer on the map.

Roads

The A470 from Cardiff is, as far as its junction with the A465 Heads of the Valleys road, a dual-carriageway providing direct access to Taff's Well, Pontypridd, Abercynon and Merthyr Tydfil. It links with the A4059 from Abercynon, Aberdare and Hirwaun; the A472 from Ystrad Mynach and Pontypool, and the A4054 from Quakers Yard. The First Minister has repeated on a number of occasions the promise that the dualling of the A465 will be complete by 2020.[18]

| Section | From / To | Commencement date | Completion date | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Abergavenny to Gilwern | February 2005 | May 2008 | Complete |

| 2 | Gilwern to Brynmawr | December 2014[19] | Due by 2018 | Under construction |

| 3 | Brynmawr to Tredegar | January 2013 | September 2015 | Complete |

| 4 | Tredegar to Dowlais Top | March 2002 | November 2004 | Complete |

| 5 | Dowlais Top to A470 | Late 2018 | Due by 2020 | Planned |

| 6 | A470 Junction to Hirwaun | Late 2018 | Due by 2020 | Planned |

Public transport

Stagecoach in South Wales provides bus services linking many towns and villages directly to Cardiff city centre.

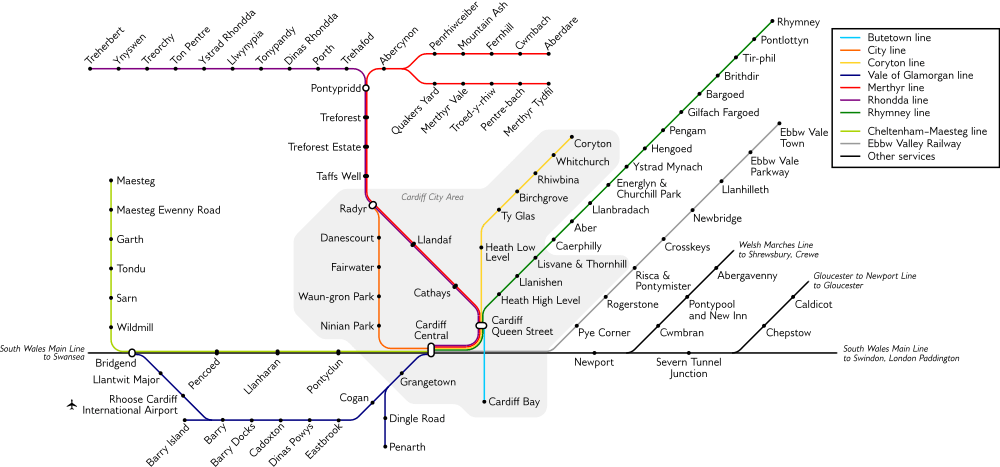

Many settlements in the Valleys are served by the Valley Lines network, an urban rail network radiating from Cardiff which links them to the city's stations, principally Cardiff Queen Street and Cardiff Central, with connections onto the South Wales Main Line. There are six main lines from Central Cardiff to the Valleys:

- Valley Lines via Cardiff Queen Street

- Rhondda Line to Pontypridd to Treherbert

- Merthyr Line to Pontypridd and Abercynon continuing to either Aberdare or Merthyr Tydfil, plus the freight-only section beyond Aberdare to Hirwaun

- Rhymney Line to Rhymney, plus the freight-only line from Ystrad Mynach to Cwmbargoed.[20]

- Routes via the South Wales Main Line

- Maesteg Line to Bridgend and Maesteg

- Ebbw Valley Railway to Ebbw Vale

- Welsh Marches Line to Abergavenny continuing to North Wales and North West England

Listed from west to east

- Gwendraeth valley

- Amman Valley

- Loughor Valley (forms the historic boundary between Carmarthenshire and Glamorgan)

- Swansea Valley (Tawe Valley)

- Dulais Valley

- Vale of Neath

- Afan Valley

- Llynfi Valley

- Garw Valley

- Ogmore Valley

- Rhondda Valley

- Cynon Valley

- Aber Valley

- Ely Valley

- Taff Valley

- Taff Bargoed Valley

- Rhymney Valley (forms the historic boundary between Glamorgan and Monmouthshire)

- Sirhowy Valley

- Ebbw Valley

- Ebbw Fach Valley

- Llwyd Valley

References

- Minchinton, W. E., ed. (1969) Industrial South Wales, 1750–1914

- Davies, John; The Welsh Academy Encyclopedia of Wales. Cardiff: University of Wales Press 2008.

- Welsh Assembly Government (2008) People, Places, Futures – The Wales Spatial Plan 2008 Update.

- Jenkins, P. (1992) A History of Modern Wales, 1536–1990. Harlow: Longman.

- John (1980), p. 590

- John (1980), p. 595

- John (1980), p. 596

- John (1980), p. 588

- John (1980), p. 589

- Davies (2008), p. 748

- Hawley, Mark (2017). Guidelines for Mine Waste Dump and Stockpile Design. CRC Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-1138197312.

- Morris, Steven (2016-10-21). "Aberfan: Prince of Wales among those marking disaster's 50th anniversary". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2019-10-08.

- "Blunkett told of 'Valleys drug menace'". BBC News. 1 October 2002.

- David, R. et al. (2003) The Socio-Economic Characteristics of the South Wales Valleys in a Broader Context. A report for the Welsh Assembly Government.

- "Wales: Its People". Statistics.gov.uk. Retrieved 2013-05-06.

- "Turning heads... a strategy for the Heads of the Valleys. Welsh Assembly Government 2006". Adjudicationpanelwales.org.uk. Retrieved 2013-05-06.

- "Restoration of Newport-Ebbw Vale rail link on track for 2021". South Wales Argus. Retrieved 2019-12-11.

- "Welsh Assembly Government (2009) ''National Transport Plan''" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-08-06. Retrieved 2013-05-06.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 21 February 2015. Retrieved 2015-02-21.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Network Rail Route Plans 2009. Route 15, South Wales Valleys" (PDF). Retrieved 2013-05-06.

Bibliography

- John, Arthur H. (1980). Glamorgan County History, Volume V, Industrial Glamorgan from 1700 to 1970. Cardiff: University of Wales Press.