Tapanahony

Tapanahoni is a resort in Suriname, located in the Sipaliwini District. Its population at the 2012 census was 13,808.[3] Tapanahoni is a part of Sipaliwini which has no capital, but is directly governed from Paramaribo.[4] Tapanahony is an enormous resort which encompasses a quarter of the country of Suriname.[5] The most important town is Diitabiki (old name: Drietabbetje) which is the residence of the granman of the Ndyuka people since 1950, and the location of the oracle.[6]

Tapanahoni | |

|---|---|

Diitabiki (1907) | |

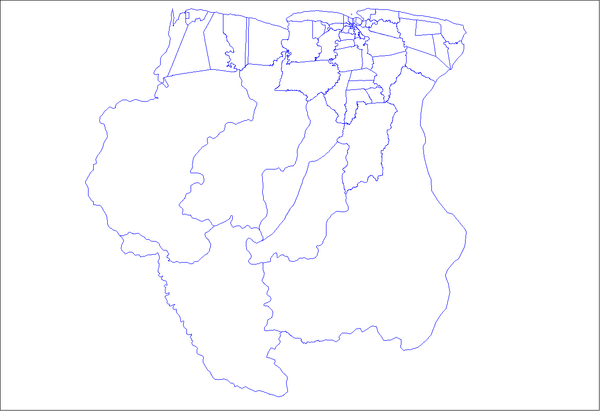

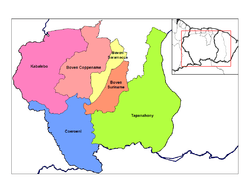

Map showing the resorts of Sipaliwini District.

Tapanahony | |

| Country | |

| District | Sipaliwini District |

| Area | |

| • Total | 38,965 km2 (15,044 sq mi) |

| Population (2012)[2] | |

| • Total | 13,808 |

| • Density | 0.35/km2 (0.92/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC-3 (AST) |

The disputed area of south-east Suriname between the Marowini (the eastern tributary river) and the Litani rivers belongs to the Tapanahoni resort.[7]

History

The Ndyuka people are of African descent, and were shipped as slaves to Suriname in the 17-18th century to work on Dutch-owned colonial plantations. The escaped slaves moved into the rainforest, and banded together.[8] There were frequent clashes between the colonists and the Ndyuka, however in 1760, a peace treaty was signed granting the Ndyuka autonomy.[9] From 1761, the Ndyuka gradually moved southwards in order to protected themselves from the colonists, and started to build camps on the Tapanahoni River dispelling the indigenous Tiriyó. Slaves who had recently fled from Armina[lower-alpha 1] and Boven Commewijne were stationed near the confluence of the Tapanahoni and Lawa River to guard against attacks by the Aluku.[11] In December 1791, Philip Stoelman founded a military outpost on Stoelmanseiland, thus establishing a militarised border between the Ndyuka held territory and the Colony of Suriname.[12] In 1857, the granman of the Ndyuka was given a yearly allowance of ƒ1,000 (2018: €10,233[13]) by the Government of Suriname.[11]

The area was an unknown area for the white settlers, and was not explored until the beginning of the 20th century.[14] Still the explorers first had to request an audience with the granman. Gerard Versteeg, leader of a 1904 expedition, expressed his frustration in his dairy about having to wait four days before being granted permission to continue his journey.[15]

In 1983, the Sipaliwini District was created.[16] On 11 September 2019,[17] a new resort was created out of Tapanahony, and is called Pamacca. The Pamacca resort is the northern part of Tapanahony, and mainly inhabited by the Paramaccan people.[16][17]

Villages

The resort of Tapanahony consists of about 49 Ndyuka villages and 14 indigenous villages.[1]

| Name | Tribe | Clinic | School | Church |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Akani Pata | Wayana | no | no | no |

| Aloepi 2 | Tiriyó | ? | ? | ? |

| Antonio do Brinco | not applicable | no | no | yes[18] |

| Apetina | Wayana | yes | yes | no |

| Benzdorp | Ndyuka | no | no | no |

| Cottica | Aluku[19] | yes | yes | no |

| Diitabiki | Ndyuka | yes | yes | Moravian |

| Godo Holo | Ndyuka | via Diitabiki | yes | two |

| Kawemhakan | Wayana | yes | no | no |

| Kumakahpan | Wayana | no | no | no |

| Moitaki | Ndyuka | no | yes | no |

| Paloemeu | Wayana | yes | no | yes |

| Pelelu Tepu | Tiriyó | yes | yes | yes |

| Poeketi | Ndyuka | no | no | no |

| Pontoetoe | Ndyuka | ? | ? | ? |

| Tutu Kampu | Wayana | no | no | no |

Source: Planning Office Suriname - Districts 2009-2013 - Table 3.1

Notes

- Post Armina was a guard post on the Marowijne River.[10]

References

- "Planning Office Suriname - Districts" (PDF). Planning Office Suriname (in Dutch). Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- "2012 Census Resorts Suriname" (PDF). Spang Staging. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- Statoids.com

- "Districten". Suriname View (in Dutch). Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- "Country map - Administrative structure - Population density of Suriname". Geo Ref. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- "Een geschiedenis van de Surinaamse literatuur. Deel 2". Digital Library for Dutch Literature (in Dutch). 2002. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- "Goudwinning met toestemming Suriname en Frankrijk". Star Nieuws (in Dutch). Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- "Suriname and the Maroons". Milwaukee Public Museum. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- "The Ndyuka Treaty Of 1760: A Conversation with Granman Gazon". Cultural Survival. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- "Disktrikt Marowijne 2" (in Dutch). Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- "Encyclopaedie van Nederlandsch West-Indië - Page 154 - Boschnegers" (PDF). Digital Library for Dutch Literature (in Dutch). 1916. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- Silvia de Groot (1970). "Rebellie der Zwarte Jagers. De nasleep van de Bonni-oorlogen 1788-1809". De Gids (in Dutch).

- "De waarde van de gulden / euro". Internationaal Instituut voor Sociale Geschiedenis (in Dutch). Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- "Distrikt Sipaliwini". Suriname.nu (in Dutch). Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- "Elsevier's Geïllustreerd Maandschrift. Jaargang 15". Digital Library for Dutch Literature (in Dutch). 1905. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- "Distrikt Sipaliwini". Suriname.nu (in Dutch). Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- "Paamaka en Ndyuka leggen grens vast". Regional Development.gov.sr (in Dutch). Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- "La Vie en face". Une Saison en Guyane (in French). Retrieved 6 July 2020.

- "Parcours La Source". Parc-Amazonien-Guyane (in French). Retrieved 1 June 2020.