Alkmaar, Suriname

Alkmaar (Sranan Tongo: Goedoefrow[2]) is a resort in Suriname, located in the Commewijne District. Its population at the 2012 census was 5,561.[3]

Alkmaar Goedoefrow | |

|---|---|

Resort and town | |

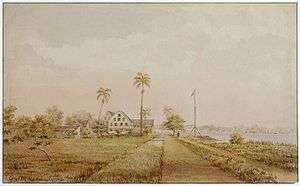

The plantations 'Nijd en Spijt' and 'Alkmaar' (1860) | |

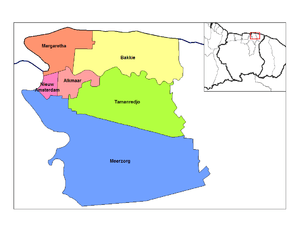

Map showing resorts in Commewijne District.

Alkmaar | |

| Coordinates: 5°51′N 55°2′W | |

| Country | |

| District | Commewijne District |

| Area | |

| • Total | 81 km2 (31 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 0 m (0 ft) |

| Population (2012) | |

| • Total | 5,561[1] |

| Time zone | UTC-3 (AST) |

| Climate | Af |

History

The plantation was named after the city of Alkmaar in the Dutch province of North Holland where Jacobus Hengeveldt, the founder was born.[4] The city was named after the plantation. Alkmaar has regional significance as a government post and a medical centre. The Moravian Church (EMEA) is an important center of Christian consignment among the Hindus, and started when P.M. Legêne arrived in Alkmaar. The church was built in 1923, partly financed by fundraising from the Netherlands. A children's home was also setup.[5]

In the 18th century Alkmaar became a notable coffee producing location. Construction of the plantation was consigned to James Hengeveldt in 1745. After the completion of Fort at New Amsterdam in 1746, the land at the mouth of the Commewijne River was cleared to make way for the plantation which opened in 1747.[6] Charles Godeffroy then took over the plantation.[4] In 1884, the plantation ceased its operation due to low sugar prices.[7]. In 1894, the government bought the grounds in order to distribute it to small farmers.[4] The motivation was to entice the contract workers from Java to remain in Suriname.[8] The Javanese still form the largest ethnic group.[1] In 1908, there were 699 farmers producing 20,000 kg of cacao, 50,000 kg of rice, and 57,000 bunches of bananas.[4]

The village and former sugarcane factory of Mariënburg is located close to Alkmaar.[9] The villages of Johan & Margaretha and Frederiksdorp on the other side of the river, can be reached by a ferry from Mariënburg.[10]

Notable people

References

- "Resorts in Suriname Census 2012" (PDF). Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- "Alkmaar". Alkmaar voor Alkmaar (in Dutch). Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- Statoids.com

- "Plantage Alkmaar". Suriname Plantages (in Dutch). Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- "Suriname 1599-1975: Weeshuizen". University of Amesterdam (in Dutch). Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- National Archives of Suriname Archived 2007-10-10 at the Wayback Machine, (in Dutch)

- "Encyclopaedie van Nederlandsch West-Indië - Page 355 - Handels-Maatschappij (de Nederlandsche)" (PDF). Digital Library for Dutch Literature (in Dutch). 1916. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- "Sranan. Cultuur in Suriname page 53". Digital Library for Dutch Literature. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- "Marienburg Suriname". Suriname.nu (in Dutch). Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- "Over Ons". Frederiksdorp.com (in Dutch). Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- "Frits E.M. Mitrasing". Suriname.nu (in Dutch). Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- "Soekhai (VHP): 'Voor 650 miljoen US gaan we over op biobrandstof'". Star Nieuws (in Dutch). Retrieved 12 May 2020.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Alkmaar, Suriname. |