Tanning (leather)

Tanning is the process of treating skins and hides of animals to produce leather. A tannery is the place where the skins are processed.

Tanning hide into leather involves a process which permanently alters the protein structure of skin, making it more durable and less susceptible to decomposition, and also possibly coloring it.

Before tanning, the skins are dehaired, degreased, desalted and soaked in water over a period of six hours to two days. Historically this process was considered a noxious or "odoriferous trade" and relegated to the outskirts of town.

Traditionally, tanning used tannin, an acidic chemical compound from which the tanning process draws its name. The use of a chromium (III) solution was adopted by tanners during the Industrial Revolution.

History

The English word for tanning is from medieval Latin tannāre, derivative of tannum (oak bark), from French tan (tanbark), from old-Cornish tann (red oak). These terms are related to the hypothetical Proto-Indo-European *dʰonu meaning 'fir tree'. (The same word is source for Old High German tanna meaning 'fir', related to modern Tannenbaum). Despite the linguistic confusion between quite different conifers and oaks, the word tan referring to dyes and types of hide preservation is from the Gaulic use referencing the bark of oaks (the original source of tannin), and not fir trees.

Ancient civilizations used leather for waterskins, bags, harnesses and tack, boats, armour, quivers, scabbards, boots, and sandals. Tanning was being carried out by the inhabitants of Mehrgarh in Pakistan between 7000 and 3300 BCE.[1] Around 2500 BCE, the Sumerians began using leather, affixed by copper studs, on chariot wheels.

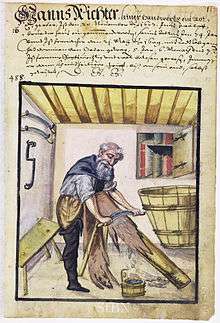

Formerly, tanning was considered a noxious or "odoriferous trade" and relegated to the outskirts of town, among the poor. Indeed, tanning by ancient methods is so foul smelling that tanneries are still isolated from those towns today where the old methods are used. Skins typically arrived at the tannery dried stiff and dirty with soil and gore. First, the ancient tanners would soak the skins in water to clean and soften them. Then they would pound and scour the skin to remove any remaining flesh and fat. Hair was removed by either soaking the skin in urine,[2] painting it with an alkaline lime mixture, or simply allowing the skin to putrefy for several months then dipping it in a salt solution. After the hair was loosened, the tanners scraped it off with a knife. Once the hair was removed, the tanners would "bate" (soften) the material by pounding dung into the skin, or soaking the skin in a solution of animal brains. Bating was a fermentative process which relied on enzymes produced by bacteria found in the dung. Among the kinds of dung commonly used were those of dogs or pigeons.[3]

Historically the actual tanning process used vegetable tanning. In some variations of the process, cedar oil, alum, or tannin was applied to the skin as a tanning agent. As the skin was stretched, it would lose moisture and absorb the agent.

Following the adoption in medicine of soaking gut sutures in a chromium (III) solution after 1840, it was discovered that this method could also be used with leather and thus was adopted by tanners.[4]

Preparation

The tanning process begins with obtaining an animal skin. When an animal skin is to be tanned, the animal is killed and skinned before the body heat leaves the tissues.[5] This can be done by the tanner, or by obtaining a skin at a slaughterhouse, farm, or local fur trader.

Preparing hides begins by curing them with salt. Curing is employed to prevent putrefaction of the protein substance (collagen) from bacterial growth during the time lag from procuring the hide to when it is processed. Curing removes water from the hides and skins using a difference in osmotic pressure. The moisture content of hides and skins is greatly reduced, and osmotic pressure increased, to the point that bacteria are unable to grow. In wet-salting, the hides are heavily salted, then pressed into packs for about 30 days. In brine-curing, the hides are agitated in a saltwater bath for about 16 hours. Curing can also be accomplished by preserving the hides and skins at very low temperatures.

Beamhouse operations

The steps in the production of leather between curing and tanning are collectively referred to as beamhouse operations. They include, in order, soaking, liming, removal of extraneous tissues (unhairing, scudding and fleshing), deliming, bating or puering, drenching, and pickling.[6][7]

Soaking

In soaking, the hides are soaked in clean water to remove the salt left over from curing and increase the moisture so that the hide or skin can be further treated.

To prevent damage of the skin by bacterial growth during the soaking period, biocides, typically dithiocarbamates, may be used. Fungicides such as 2-thiocyanomethylthiobenzothiazole may also be added later in the process, to protect wet leathers from mold growth. After 1980, the use of pentachlorophenol and mercury-based biocides and their derivatives was forbidden.[8]

Liming

After soaking, the hides are treated with milk of lime (a basic agent) typically supplemented by "sharpening agents" (disulfide reducing agents) such as sodium sulfide, cyanides, amines, etc.

This:

- Removes the hair and other keratinous matter

- Removes some of the interfibrillary soluble proteins such as mucins

- Swell up and split up the fibres to the desired extent

- Removes the natural grease and fats to some extent

- Brings the collagen in the hide to a proper condition for satisfactory tannage

The weakening of hair is dependent on the breakdown of the disulfide link of the amino acid cystine, which is the characteristic of the keratin class of proteins that gives strength to hair and wools (keratin typically makes up 90% of the dry weight of hair). The hydrogen atoms supplied by the sharpening agent weaken the cystine molecular link whereby the covalent disulfide bond links are ultimately ruptured, weakening the keratin. To some extent, sharpening also contributes to unhairing, as it tends to break down the hair proteins.

The isoelectric point of the collagen (a tissue-strengthening protein unrelated to keratin) in the hide is also shifted to around pH 4.7 due to liming.

Unhairing and scudding

Unhairing agents used at this time include sodium sulfide, sodium hydroxide, sodium hydrosulfite, calcium hydrosulfide, dimethyl amine, and sodium sulfhydrate. The majority of hair is then removed mechanically, initially with a machine and then by hand using a dull knife, a process known as scudding.

Deliming and bating

The pH of the collagen is brought down to a lower level so the enzymes may act on it, in a process known as deliming. Depending on the end use of the leather, hides may be treated with enzymes to soften them, a process called bating. In modern tanning, these enzymes are purified agents, and the process no longer requires bacterial fermentation (as from dung-water soaking) to produce them.[9]

Pickling

Once bating is complete, the hides and skins are treated first with common salt (sodium chloride) and then with sulfuric acid, in case a mineral tanning is to be done. This is done to bring down the pH of collagen to a very low level so as to facilitate the penetration of mineral tanning agent into the substance. This process is known as pickling. The salt penetrates the hide twice as fast as the acid and checks the ill effect of the sudden drop of pH.

Process

Chrome tanning

Chromium(III) sulfate ([Cr(H2O)6]2(SO4)3) has long been regarded as the most efficient and effective tanning agent.[10][11] Chromium(III) compounds of the sort used in tanning are significantly less toxic than hexavalent chromium, although the latter arises in inadequate waste treatment. Chromium(III) sulfate dissolves to give the hexaaquachromium(III) cation, [Cr(H2O)6]3+, which at higher pH undergoes processes called olation to give polychromium(III) compounds that are active in tanning,[12] being the cross-linking of the collagen subunits. The chemistry of [Cr(H2O)6]3+ is more complex in the tanning bath rather than in water due to the presence of a variety of ligands. Some ligands include the sulfate anion, the collagen's carboxyl groups, amine groups from the side chains of the amino acids, and masking agents. Masking agents are carboxylic acids, such as acetic acid, used to suppress formation of polychromium(III) chains. Masking agents allow the tanner to further increase the pH to increase collagen's reactivity without inhibiting the penetration of the chromium(III) complexes.

Collagen is characterized by a high content of glycine, proline, and hydroxyproline, usually in the repeat -gly-pro-hypro-gly-.[13] These residues give rise to collagen's helical structure. Collagen's high content of hydroxyproline allows for significant cross-linking by hydrogen bonding within the helical structure. Ionized carboxyl groups (RCO2−) are formed by hydrolysis of the collagen by the action of hydroxide. This conversion occurs during the liming process, before introduction of the tanning agent (chromium salts). The ionized carboxyl groups coordinate as ligands to the chromium(III) centers of the oxo-hydroxide clusters.

Tanning increases the spacing between protein chains in collagen from 10 to 17 Å.[14] The difference is consistent with cross-linking by polychromium species, of the sort arising from olation and oxolation.

_Tanning_Mechanisms.tif.jpg)

Prior to the introduction of the basic chromium species in tanning, several steps are required to produce a tannable hide. The pH must be very acidic when the chromium is introduced to ensure that the chromium complexes are small enough to fit in between the fibers and residues of the collagen. Once the desired level of penetration of chrome into the substance is achieved, the pH of the material is raised again to facilitate the process. This step is known as basification. In the raw state, chrome-tanned skins are greyish-blue, so are referred to as wet blue. Chrome tanning is faster than vegetable tanning (less than a day for this part of the process) and produces a stretchable leather which is excellent for use in handbags and garments.

Subsequent to application of the chromium agent, the bath is treated with sodium bicarbonate to increase the pH to 4.0–4.3, which induces cross-linking between the chromium and the collagen. The pH increase is normally accompanied by a gradual temperature increase up to 40 °C.[15] Chromium's ability to form such stable bridged bonds explains why it is considered one of the most efficient tanning compounds. Chromium-tanned leather can contain between 4 and 5% of chromium.[14] This efficiency is characterized by its increased hydrothermal stability of the skin, and its resistance to shrinkage in heated water.[11]

Vegetable tanning

Vegetable tanning uses tannins (a class of polyphenol astringent chemicals), which occur naturally in the bark and leaves of many plants. Tannins bind to the collagen proteins in the hide and coat them, causing them to become less water-soluble and more resistant to bacterial attack. The process also causes the hide to become more flexible. The primary barks processed in bark mills and used in modern times are chestnut, oak, redoul, tanoak, hemlock, quebracho, mangrove, wattle (acacia; see catechol), and myrobalans from Terminalia spp., such as Terminalia chebula. Hides that have been stretched on frames are immersed for several weeks in vats of increasing concentrations of tannin. Vegetable-tanned hide is not very flexible. It is used for luggage, furniture, footwear, belts, and other clothing accessories.

Alternative chemicals

Wet white is a term used for leathers produced using alternative tanning methods that produce an off-white colored leather. Like wet blue, wet white is also a semifinished stage. Wet white can be produced using aldehydes, aluminum, zirconium, titanium, or iron salts, or a combination thereof. Concerns with the toxicity and environmental impact of any chromium (VI) that may form during the tanning process have led to increased research into more efficient wet white methods.

Natural tanning

The conditions present in bogs, including highly acidic water, low temperature, and a lack of oxygen, combine to preserve but severely tan the skin of bog bodies.

Tawing

Tawing is a method that uses alum and aluminium salts, generally in conjunction with other products such as egg yolk, flour, and other salts. The leather becomes tawed by soaking in a warm potash alum and salts solution, between 20 and 30 °C. The process increases the leather's pliability, stretchability, softness, and quality. Adding egg yolk and flour to the standard soaking solution further enhances its fine handling characteristics. Then, the leather is air dried (crusted) for several weeks, which allows it to stabilize. Tawing is traditionally used on pigskins and goatskins to create the whitest colors. However, exposure and aging may cause slight yellowing over time and, if it remains in a wet condition, tawed leather will suffer from decay. Technically, tawing is not tanning.[16]

Depending on the finish desired, the hide may be waxed, rolled, lubricated, injected with oil, split, shaved and dyed. Suedes, nubucks, etc. are finished by raising the nap of the leather by rolling with a rough surface.

The first stage is the preparation for tawing. The second stage is the actual tawing and other chemical treatment. The third stage, known as retawing, applies retawing agents and dyes to the material to provide the physical strength and properties desired depending on the end product. The fourth and final stage, known as finishing, is used to apply finishing material to the surface or finish the surface without the application of any chemicals if so desired.

Health and environmental impact

The tanning process involves chemical and organic compounds that can have a detrimental effect on the environment. Agents such as chromium, vegetable tannins, and aldehydes are used in the tanning step of the process. However, other processes and chemicals are also involved.[17] Chemicals used in tanned leather production increase the levels of chemical oxygen demand and total dissolved solids in water when not disposed of responsibly. These processes also use large quantities of water and produce large amounts of pollutants.[18]

The tannery in León, Nicaragua, has also been identified as a source of major river pollution.[19]

Boiling and sun drying can oxidize and convert the various chromium(III) compounds used in tanning into carcinogenic hexavalent chromium, or chromium(VI). This hexavalent chromium runoff and scraps are then consumed by animals, in the case of Bangladesh, chickens (the nation's most common source of protein). Up to 25% of the chickens in Bangladesh contained harmful levels of hexavalent chromium, adding to the national health problem load.[20]

Chromium is not solely responsible for these diseases. Methylisothiazolinone, which is used for microbiological protection (fungal or bacterial growth), causes problems with the eyes and skin. Anthracene, which is used as a leather tanning agent, can cause problems in the kidneys and liver and is also considered a carcinogen. Formaldehyde and arsenic, which are used for leather finishing, cause health problems in the eyes, lungs, liver, kidneys, skin, and lymphatic system and are also considered carcinogens.[18] The waste from leather tanneries is detrimental to the environment and the people who live in it. The use of old technologies plays a large factor in how hazardous wastewater results in contaminating the environment. This is especially prominent in small and medium-sized tanneries in developing countries.[21]

The UN Leather Working Group (LWG) "provides an environmental audit protocol, designed to assess the facilities of leather manufacturers,"[22] for " traceability, energy conservation, [and] responsible management of waste products."[23]

Alternatives

As an alternative to tanning, hides can be dried to produce rawhide rather than leather.

Associated processes

Leftover leather would historically be turned into glue. Tanners would place scraps of hides in a vat of water and let them deteriorate for months. The mixture would then be placed over a fire to boil off the water to produce glue.

A tannery may be associated with a grindery, originally a whetstone facility for sharpening knives and other sharp tools, but later could carry shoemakers' tools and materials for sale.[24]

There are several solid and waste water treatment methodologies currently being researched, such as anaerobic digestion of solid wastes and wastewater sludge.

See also

References

- Possehl, Gregory L. (1996). Mehrgarh in Oxford Companion to Archaeology, edited by Brian Fagan. Oxford University Press.

- Kumar, Mohi (August 20, 2013). "From Gunpowder to Teeth Whitener: The Science Behind Historic Uses of Urine". smithsonian.com. Retrieved December 16, 2018.

- Johnson, Steven (2006). The Ghost Map. New York: Riverhead Books. pp. 4, 263. ISBN 978-1-59448-269-4.

- "A history of new ideas in tanning - Leather International". www.leathermag.com. Archived from the original on 2 January 2017. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- "What is Vegetable Tanned Leather?". The Wallet Shoppe. 2018-03-07.

- "Etherington and Roberts Dictionary". Foundation of the American Institute for Conservation. 2011-03-10. Archived from the original on 2011-02-25. Retrieved 2011-10-14.

- "3. Tanneries, Description of the Tanning Process". Food and Agriculture Organization. Archived from the original on 2011-08-22. Retrieved 2011-10-14.

- "Hazardous Chemicals in Clothing" GreenPeace.org. Retrieved 2018-11-13.

- Covington, Tony (31 August 2002). "Letters: Pure dog dung". New Scientist. Archived from the original on 13 April 2016. Retrieved 6 January 2016.

- Wilson, J.A. The Chemistry of Leather Manufacture. The Chemical Catalog Company, Inc. New York 1923.

- Covington, A. "Modern Tanning Chemistry" Chemical Society Review 1997, volume 26, 111–126. doi:10.1039/CS9972600111

- Harlan, J.; Feairheller, S.; Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1977, 86A, 425.

- Heidemann, E.; J. Soc. Leather Technol. Chem., 1982, 66, 21.

- Gustavson, K.H. "The Chemistry of Tanning Processes" Academic Press Inc., New York, 1956.

- Heidemann, E.; Leather. Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry,2005. doi:10.1002/14356007.a15_259

- "Etherington & Roberts. Dictionary--tawing". cool.conservation-us.org. Archived from the original on 29 June 2017. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- Lofrano, G., Meric, S., Balci, G., & Orhon, D. (2013). Chemical and biological treatment technologies for leather tannery chemicals and wastewaters: A review. Science of Total Environment, 461-462, 265-281.

- Das, Mukul; Dwivedi, Premendra D.; Yadav, Ashish; Dixit, Sumita (2015). "Toxic hazards of leather industry and technologies to combat threat: a review". Journal of Cleaner Production. 87: 39–49. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.10.017. Archived from the original on 2016-03-24. Retrieved 2015-11-07.

- Rodríguez Area, Clara. "Strategy for the implementation of DEWATS* for industrial effluents in León (Nicaragua)" (PDF). Hafencity University Hamburg. Resource Efficiency in Architecture and Planning (REAP), Hafencity University Hamburg. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- http://www.gulf-times.com/bangladesh/245/details/398475/toxic-poultry-feed-threatens-bangladesh’s-poor Archived 2014-09-07 at the Wayback Machine

- Blackman, Allen; Kildegaard, Arne (2010-09-18). "Clean technological change in developing-country industrial clusters: Mexican leather tanning". Environmental Economics and Policy Studies. 12 (3): 115–132. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.534.6195. doi:10.1007/s10018-010-0164-7. ISSN 1432-847X.

- "UN SDGs - Leather Working Group". Leather Working Group. Retrieved 2019-12-08.

- Martinko, Katherine (December 6, 2019). "KEEN has launched its 'most durable, consciously-constructed' boot yet". TreeHugger. Retrieved 2019-12-08.

- The Oxford English Dictionary, Second edition, Volume VI, ISBN 0-19-861218-4 entry: "grindery"

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tanning. |