Boiled leather

Boiled leather, often referred to by its French translation, cuir bouilli (French: [kɥiʁ buji]), was a historical material for various uses common in the Middle Ages and Early Modern Period. It was leather that had been treated so that it became tough and rigid, as well as able to hold moulded decoration. It was the usual material for the robust carrying-cases that were made for important pieces of metalwork, instruments such as astrolabes, personal sets of cutlery, books, pens and the like.[1] It was used for some armour, being both much cheaper and much lighter than plate armour, but could not withstand a direct blow from a blade, nor a gunshot.[2]

Alternative names are "moulded leather" and "hardened leather". In the course of making the material it becomes very soft, and can be impressed into a mould to give it the desired shape and decoration, which most surviving examples have. Pieces such as chests and coffers also usually have a wooden inner core.[3]

Various recipes for making cuir bouilli survive, and do not agree with each other; probably there were a range of recipes, partly reflecting different final uses. Vegetable-tanned leather is generally specified. Scholars have debated the subject at length and attempted to recreate the historical material. Many, but not all, sources agree that actual boiling of the leather was not part of the process, but immersion in water, cold or hot, was.[4]

Military use

.jpg)

Cuir bouilli was used for cheap and light armour, although it was much less effective than plate armour, which was extremely expensive and too heavy for much to be worn by infantry (as opposed to knights fighting on foot). However, cuir bouilli could be reinforced against slashing blows by the addition of metal bands or strips, especially in helmets. Modern experiments on simple cuir bouilli have shown that it can reduce the depth of an arrow wound considerably, especially if coated with a crushed mineral facing mixed with glue, as one medieval Arab author recommended.[5]

In addition, "armour based on hide has the unique advantage that it can, in extremis, provide some nutrition", when actually boiled. Josephus records that the Jewish defenders in the Siege of Jerusalem in AD 70 were reduced to eating their shields and other leather kit, as was the Spanish expedition of Tristan de Luna in 1559.[6]

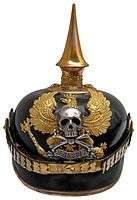

Versions of cuir bouilli were used since ancient times, especially for shields, in many parts of the world.[7] Although in general leather does not survive long burial, and excavated archaeological evidence for it is rare, an Irish shield of cuir bouilli with wooden formers, deposited in a peat bog, has survived for some 2,500 years.[8] It was commonly used in the Western world for helmets; the pickelhaube, the standard German helmet, was not replaced by a steel stahlhelm until 1916, in the midst of World War I.[9] As leather does not conduct heat the way metal does, firemen continued to use boiled leather helmets until WW2, and the invention of strong plastics.[10]

The word cuirass for a breastplate indicates that these were originally made of leather.[11] In the Late Middle Ages, the heyday of plate armour, cuir bouilli continued to be used even by the rich for horse armour and often for tournament armour,[12] as well as by ordinary infantry soldiers. Tournaments were increasingly regulated in order to reduce the risk to life, and in 1278 Edward I of England organized one in Windsor Great Park at which cuir bouilli armour was worn, and the king provided swords made of whale bone and parchment.[13]

.jpg)

The account of the Battle of Agincourt in 1415 by Jean de Wavrin, who was present on the French side, describes the crucial force of English longbowmen as having on their heads either cuir bouilli helmets, or wicker with iron strips, or nothing (the last, he says, were also barefoot).[14]

A few pieces of Roman horse armour in cuir bouilli have been excavated. Evidence from documents such as inventories show that it was common in the late Middle Ages and Renaissance, and used by the highest ranks, but survivals are very few.[15] In 1547 the Master of Armoury in the Tower of London ordered 46 sets of bards and crinets in preparation for the final invasion of Scotland in the war known as the Rough Wooing.[16] In September that year the English cavalry were crucial in the decisive victory at the Battle of Pinkie Cleugh. The German Count Palatine of the Rhine had six sets of cuir bouilli horse armour for his and his family's use in the 16th century. Often the shaffron for the horse's head would be in steel, though leather ones are also known.[17]

Cuir bouilli was also very common for scabbards. However surviving specimens of leather armour are rare, more so than the various types of civilian containers. It is believed that many leather pieces are depicted in sculpted tomb monuments, where they are more highly decorated than metal pieces would have been.[18] Cuir bouilli was also often used for elaborate figurative crests on some helmets.

The material is mentioned in Froissart's Chronicles of the Hundred Years' War,[19] and Geoffrey Chaucer, in his Canterbury Tales, written in the late 1300s, says of the knight Sir Thopas:[20]

Hise jambeux were of quyrboilly, |

His jambeaux were of cuir-bouilli, |

(Note: jambeaux are greaves – shin armour).

The large decorative crests that came to top some helmets in the late Middle Ages were often made of cuir bouilli, as is the famous example belonging to the Black Prince and hung with other "achievements" over his tomb in Canterbury Cathedral.[21] His wooden shield also has the heraldic animals appliqued in cuir bouilli.[22]

Examples of other uses

As well as the crests on helmets described above, cuir bouilli was probably used sculpturally in various contexts, over a wood or plaster framework where necessary. When Henry V of England died in France, his effigy in cuir bouilli was placed on top of his coffin for the journey back to England.[23]

A near life-size crucifix in the Vatican Museums is in cuir bouilli over wood. This is of special interest to art historians because it was made in 1540 as a replica of a crucifix in silver presented by Charlemagne some 740 years before; an object of great interest as possibly the first of the long line of monumental crucifixes in Western art. In 1540 the original silver was melted down for church plate to replace that looted in the Sack of Rome in 1527. It seems likely that the leather was moulded directly from the original and it is possible that the wooden core underneath is actually the Carolingian original, with the leather replacing the sheets of silver originally fitted over the wood.[24]

Cuir bouilli has also been employed to bind books, mainly between the 9th and 14th centuries.[25] Other uses include high boots for especially tough use, which were called "postillion's boots" in England.[26] Another use was for large bottles or jugs called "blackjacks", "bombards" or "costerns". There is an English reference to these from 1373.[27]

Portable Reliquary Case, French, c. 1400, 12.6 cm long

Portable Reliquary Case, French, c. 1400, 12.6 cm long Late 15th-century box, 4 x 12 x 7.4 cm, Italian. The interior is painted.

Late 15th-century box, 4 x 12 x 7.4 cm, Italian. The interior is painted. Box, probably for ink powder, 15th-century Italian, textile interior and wood core

Box, probably for ink powder, 15th-century Italian, textile interior and wood core Book case, 15th-century Italian

Book case, 15th-century Italian_with_an_amorous_inscription_MET_sf50-53-1s3.jpg) Etui "with an amorous inscription", 1450–1500, Italian, 21 cm long

Etui "with an amorous inscription", 1450–1500, Italian, 21 cm long_with_an_amorous_inscription_MET_sf50-53-1d1.jpg) Detail of last. This piece has a wooden core.

Detail of last. This piece has a wooden core..jpg) French miner's hat, after 1840

French miner's hat, after 1840 Hunting Knife, Sharpener, and Sheath. French, c. 1880, as a fake 15th-century set.

Hunting Knife, Sharpener, and Sheath. French, c. 1880, as a fake 15th-century set. Braunschweigisches Husaren-Regiment Nr. 17, Death's Head pickelhaube

Braunschweigisches Husaren-Regiment Nr. 17, Death's Head pickelhaube- German fireman's helmet; designed for fire situations involving electricity

Notes

- Davies, 94; 24 items in the British Museum

- Ffoulkes, 97–99; Cheshire, 42; Abse; Loades, 10

- Davies, 94; Abse

- Davies, 94–98; Cheshire, 42–53; Loades, 10; Abse; Bradbury, 10

- Cheshire, 41–44, 51–53; Loades, 10; Bradbury, 10

- Cheshire, 47

- Ffoulkes, 97–100; Cheshire, 43 (Sioux)

- Davies, 94–95

- Stone, 220–221; Ward, Arthur, A Guide to Wartime Collectables, 23, 2013, Pen and Sword, ISBN 1473831067, 9781473831063, google books

- Davies, 95; 19th-century fireman's helmet from Montreal (text in French)

- Loades, 10

- Ffoulkes, 97–98

- Barker, 179

- Loades, 39; the passage in Wavrin's text is here

- Phyrr et al., 57–59; all significant survivals are listed.

- Phyrr et al., 57–58

- Phyrr et al., 58

- Ffoulkes, 97–99; Williams, 54

- Cheshire, 42

- Ffoulkes, 97–98; "The Tale of Sir Thopas". Librarius. Archived from the original on 8 August 2011. Retrieved 5 July 2017.

- St. John Hope, W.H., A Grammar of English Heraldry, 2011 revd edn, ed. Anthony Wagner, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 1107402107, 9781107402102, google books; Barker, 181

- "Black Prince's Tomb Canterbury Historical and Archaeological Society, 2015

- Frances Yates, p. 164 in Selected works. 10. Ideas and ideals in the North European Renaissance

- Lasko, 16–17

- Wijnekus, 170

- Davies, 96

- Davies, 95–96

References

- Abse, Bathsheba, in Abse, Bathsheba and Calnan, Christopher, "Leather, 2. iii, Moulding", Grove Art Online, Oxford Art Online, Oxford University Press. Web. 13 Oct. 2017, subscription required

- Barker, Juliet R.V., The Tournament in England, 1100–1400, 1986, Boydell Press, ISBN 0851159427, 9780851159423, google books

- Bradbury, Jim, The Routledge Companion to Medieval Warfare, 2004, Routledge, IBSN 1134598475, 9781134598472, google books

- Cheshire, Edward, "Cuir bouilli armour", in Why Leather?: The Material and Cultural Dimensions of Leather, ed. Harris, Susanna, 2014, Sidestone Press, ISBN 978-9088904707, google books

- Davies, Laura, "Cuir bouilli", Chapter 10 in Conservation of Leather and Related Materials, Eds. Marion Kite, Roy Thomson, 2006, Routledge, ISBN 1136415238, 9781136415234, google books

- Ffoulkes, Charles John, The Armourer and His Craft, 2008 (reprint), Cosimo, Inc., ISBN 1605204110, 9781605204116, google books

- Lasko, Peter, Ars Sacra, 800–1200, Penguin History of Art (now Yale), 1972 (nb, 1st edn.) ISBN 014056036X (2nd edition on google books)

- Loades, Mike, The Longbow, 2013, Bloomsbury Publishing, ISBN 1782000860, 9781782000860, google books

- "Phyrr et al.", Stuart W. Pyhrr, Donald J. LaRocca, Dirk H. Breiding, The Armored Horse in Europe, 1480–1620, 2005, Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, N.Y.), ISBN 1588391507, 9781588391506, fully available online

- Stone, David, The Kaiser's Army: The German Army in World War One, 2015, Bloomsbury Publishing, ISBN 1844862917, 9781844862917, google books

- Wijnekus, F.J.M., and Wijnekus, E.F.P.H., Dictionary of the Printing and Allied Industries, 2013 (2nd edn.), Elsevier, ISBN 1483289842, 9781483289847, google books

- Williams, Alan R, The Knight and the Blast Furnace: A History of the Metallurgy of Armour in the Middle Ages & the Early Modern Period, 2003, BRILL, ISBN 9004124985, 9789004124981, google books

- Wright, Thomas, The Archaeological Album; Or Museum of National Antiquities, 1845, Chapman & Hall, google books

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cuir bouilli. |