Tadef

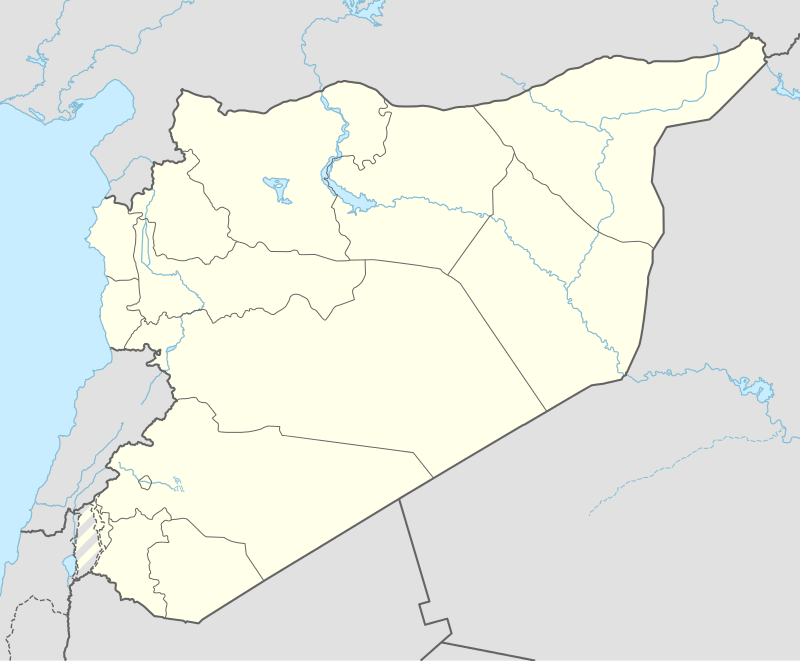

Tadef (Arabic: تادف; also spelled Tedef or Tadif) is a town just southeast of Al-Bab, about 20 miles (32 km) east of Aleppo, Syria and less than 3 kilometers (1.9 mi) south of Al Bab.[2] The town, which is the site of a shrine to the Hebrew prophet Ezra (c. 400 BCE), was a popular summer resort for the Jews of Aleppo.[3]

Tadef تادف | |

|---|---|

Town | |

Tadef Location of Tadef in Syria | |

| Coordinates: 36°20′53″N 37°31′48″E | |

| Country | |

| Governorate | Aleppo |

| District | al-Bab |

| Subdistrict | Tadef |

| Population (2004)[1] | 12,360 |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

History

The village was inhabited during the 19th century by Arabs belonging to the Aneyzeh tribe.[4] During the late 1800s, the village came under repeated attack by nomadic tribes who wished to steal sheep and cattle from the surrounding plains. Casualties were reported as the villagers were able to muster over 400 armed men to defend their flocks and herds.[5] At the time, about 20 Jewish families lived in the village,[6] which was described as a “Jewish town”.[7] Before the festival of Shavuot, Jews from Aleppo made an annual pilgrimage to the village.[6]

In 1931, there were 15 Jewish families living in the town.[8]

Association with Ezra the Scribe

Local tradition maintains that Ezra the Scribe (c. 400 BCE) paused in the town on his way from Babylon to Jerusalem and built the synagogue which still stands today.[9] In 1899, Max Freiherr von Oppenheim discovered 14th-century Hebrew inscriptions at the synagogue.[10] There is a spring near the town called Ein el-Uzir, where it is said Ezra regularly immersed himself during his sojourn there.[11][12] A tomb ascribed to Ezra is also located in the town and has been intact for many centuries.[13] On a pilgrimage to Jerusalem in 1414, Issac Elfarra of Malaga was informed:

At a distance of two (sic) miles from [Aleppo] is the tomb of Ezra the Scribe. There Ezra recorded the Torah... This village is called Taduf [and contains] a synagogue... They [also] say that every night year round a cloud ascends from the tomb of Ezra never departing.[14]

There is also another tomb attributed to Ezra near Basra, Iraq.

References

- "2004 Census Data for Nahiya Tadef" (in Arabic). Syrian Central Bureau of Statistics. Also available in English: UN OCHA. "2004 Census Data". Humanitarian Data Exchange.

- Royal Geographical Society (Great Britain) (1856). A Gazetteer of the World: Ta-Zzubin and appendix. A. Fullarton. p. 45. Retrieved 24 November 2010.

- Joseph A. D. Sutton (January 1988). Aleppo chronicles: the story of the unique Sephardeem of the Ancient Near East, in their own words. Thayer-Jacoby. p. 162. Retrieved 24 November 2010.

- Van Nostrand's engineering magazine. D. Van Nostrand. 1881. p. 414. Retrieved 24 November 2010.

- Great Britain. Parliament. House of Commons (1860). House of Commons papers. HMSO. p. 42. Retrieved 24 November 2010.

- Israel Joseph Benjamin (1859). Eight years in Asia and Africa from 1846-1855. The author. p. 49. Retrieved 24 November 2010.

- Evangelical Christendom. XIV. London: William John Johnson. 1860. p. 42. Retrieved 24 November 2010.

- Aron Rodrigue (2003). Jews and Muslims: images of Sephardi and eastern Jewries in modern times. University of Washington Press. p. 170. ISBN 978-0-295-98314-1. Retrieved 24 November 2010.

- Lucien Gubbay; Abraham Levy (June 1992). The Sephardim: their glorious tradition from the Babylonian exile to the present day. Carnell. p. 79. ISBN 978-1-85779-036-8. Retrieved 24 November 2010.

- Kevin J. Cathcart; Carmel McCarthy; John F. Healey (2004). Biblical and Near Eastern essays: studies in honour of Kevin J. Cathcart. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 317. ISBN 978-0-8264-6690-7. Retrieved 24 November 2010.

- David Sutton (30 March 2005). Aleppo: city of scholars. Mesorah. p. 12. ISBN 978-1-57819-056-0. Retrieved 24 November 2010.

- Ḥayim Sabato; Philip Simpson (2004). Aleppo tales. Toby Press. p. 53. ISBN 978-1-59264-051-5. Retrieved 24 November 2010.

- Walter P. Zenner (2000). A global community: the Jews from Aleppo, Syria. Wayne State University Press. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-8143-2791-3. Retrieved 24 November 2010.

- Josef W. Meri (2002). The cult of saints among Muslims and Jews in medieval Syria. Oxford University Press US. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-19-925078-3. Retrieved 24 November 2010.