Shaqqa

Shaqqa or Shakka (Arabic: شقا) is a Syrian town in As Suwayda Governorate in southern Syria, whose some 8,000 inhabitants are mainly Druze, descendants of those who migrated here from Lebanon in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Shaqqa شقا | |

|---|---|

Al-Qaysariye residential palace in Shaqqa | |

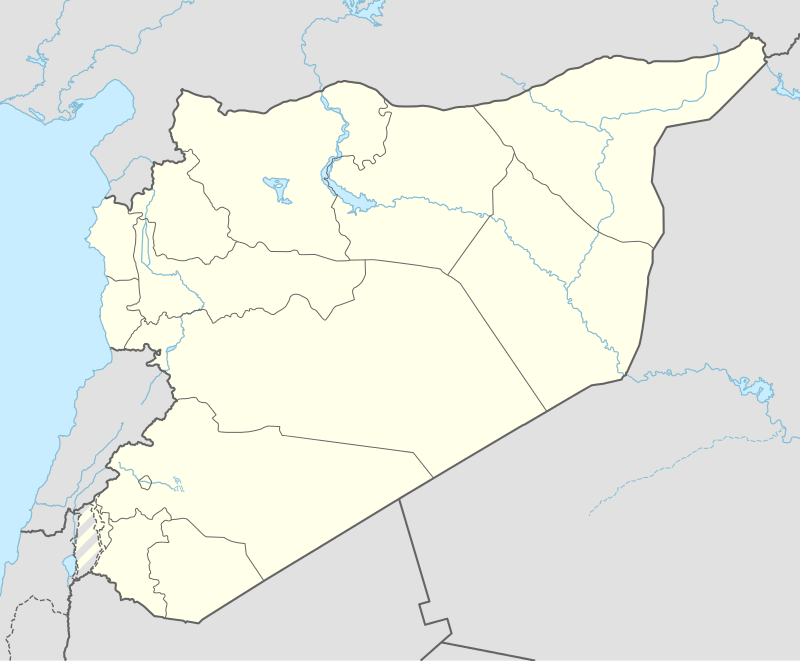

Shaqqa Location in Syria | |

| Coordinates: 32°53′50″N 36°41′53″E | |

| Country | |

| Governorate | As-Suwayda Governorate |

| District | Shahba District |

| Elevation | 1,070 m (3,510 ft) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 8,000 |

In ancient times it was known as Saccaea (transliterated also as Sakkaia). In AD 287, it was given the rank of a city and the name Maximianopolis.[1][2][3] Since it was situated in the Roman province of Arabia, it is distinguished from other cities by being called Maximianopolis in Arabia.

Location and architectural remains

Shaqqa is situated in the northern fringes of Jabal el Druze volcanic plateau at 1070 metres above sea level, 7 kilometres east of Shahba and about 25 kilometres north of As-Suwayda, the capital of the governatorate.

The ancient remains include several dwellings rich adorned both architecturally and by carvings. In addition it has:

- The enormous Al-Qaysariye, generally interpreted as the residence of the Roman governors, but more probably a small forum linked with a vast basilical hall, which was worked on in the 3rd century.[1] It has a number of rooms and halls with floral decorations.

- A Roman civil basilica, later transformed into a church dedicated to Saint George. It is believed that this church is the oldest one dedicated to the martyr Saint George on the basis of a Greek inscription naming the building for the "holy and triumphant" martyr George. It is dated to either AD 368 or 197.

- A kalybe, an old architectural style of temples typical for the Roman era southern Syria.

Maximianopolis in Arabia, doubtless the seat of a Roman garrison,[1] was a colonia,[4] the highest rank of city in the empire. It employed a calendar era that counted the years from that of Maximian's accession to the imperial throne (AD 286).[5] An inscription mentions a temple of Zeus Megistos,[6] and another bearing an epigram about the philosopher Proclus is a witness to local literary culture.[6]

Bishopric

In the 5th century Maximianopolis was an episcopal see,[1] as indicated by the participation of its bishop Severus as a signatory of the Council of Chalcedon in 451.[7][8] An inscription of 594 speaks of the local bishop, named Tiberinus, having erected a martyrium of Saint George and other martyrs.[9] Another inscription mentions a Bishop Peter.[10]

The bishopric of Maximianopolis in Arabia is included in the Catholic Church's list of titular sees.[11] In the 19th century it was mistakenly called "Maximopolis", until corrected in 1885.[10] Some sources of the same period proposed identification of Maximianopolis in Arabia with the town of Sheikh Miskin.[10]

See also

- Maximianopolis (disambiguation)

References

- UNESCO, Les villages antiques du nord de la Syrie, pp. 115-116

- Kevin Butcher, Roman Syria and the Near East (Getty Publications 2003 ISBN 978-0-89236715-3), p. 157

- Diana Darke, Syria (Bradt Travel Guides 2010 ISBN 978-1-84162314-6), p. 254

- Monuments of Syria: Shaqqa

- Johannes Koder / Marcel Restle: "Die Ära von Sakkaia (Maximianopulis) in Arabia", in: Jahrbuch der österreichischen Byzantinistik 42 (1992), pp. 79-82

- Frank R. Trombley: Hellenic Religion & Christianization, c. 370-529, E. J. Brill, Leiden 1993 (= Religions in the Graeco-Roman world, 115), vol. II, p. 344

- Eduard Schwarz (editor), Acta Conciliorum Oecumeniorum, Tom. II, vol. iii, pars 3, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin/Leipzig 1937, p. 544, No. 89

- Mansi, "Coll. Conc.", VII, 168.

- Trombley, Hellenic Religion (1993), p. 345

- Siméon Vailhé, "Maximopolis" in Catholic Encyclopedia (New York 1911)

- Annuario Pontificio 2013 (Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 2013, ISBN 978-88-209-9070-1), p. 925