Comet Swift–Tuttle

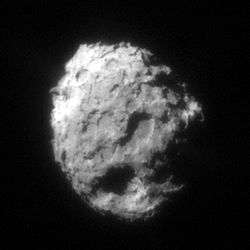

Comet Swift–Tuttle (formally designated 109P/Swift–Tuttle) is a large periodic comet with a 1995 (osculating) orbital period of 133 years that is in a 1:11 orbital resonance with Jupiter. It fits the classical definition of a Halley-type comet with a period between 20 and 200 years.[1] It was independently discovered by Lewis Swift on July 16, 1862 and by Horace Parnell Tuttle on July 19, 1862. It has a well determined orbit and has a comet nucleus 26 km in diameter.[1]

Perseid meteor, originating from Comet Swift-Tuttle, from the ISS | |

| Discovery | |

|---|---|

| Discovered by | Lewis Swift Horace Parnell Tuttle |

| Discovery date | July 16, 1862 |

| Alternative designations | 1737 N1; 1737 II; 1862 O1; 1862 III; 1992 S2; 1992 XXVIII |

| Orbital characteristics A | |

| Epoch | October 10, 1995 (JD 2450000.5) |

| Observation arc | 257 years |

| Aphelion | 51.225 AU |

| Perihelion | 0.9595 AU |

| Semi-major axis | 26.092 AU |

| Eccentricity | 0.9632 |

| Orbital period | 133.28 yr |

| Max. orbital speed | 42.6 km/s[lower-alpha 1] |

| Min. orbital speed | 0.8 km/s (2059-Dec-12) |

| Inclination | 113.45° |

| Earth MOID | 0.0009 AU (130,000 km) |

| Dimensions | 26 km[1] |

| Last perihelion | December 11, 1992[1] |

| Next perihelion | July 12, 2126[2][3] |

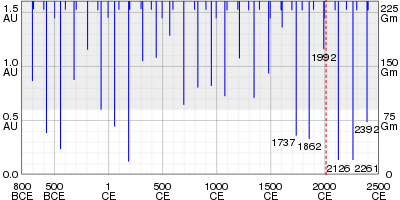

Chinese records indicate that, in 188, the comet reached apparent magnitude 0.1.[4] Observation was also recorded in 69 BC, and it was probably visible to the naked eye in 322 BC.[5] In the discovery year of 1862, the comet was as bright as Polaris.[6] The comet made a return appearance in 1992, when it was rediscovered by Japanese astronomer Tsuruhiko Kiuchi and became visible with binoculars.[7] In 2126 it will be a bright naked-eye comet reaching about apparent magnitude 0.7.[4]

After the 1862 observations it was thought that the comet would return between 1979 and 1983, but it didn't show up. However, it had been suggested in 1902 that this was the same comet as that observed by Ignatius Kegler on July 3, 1737,[8] and on this basis Brian Marsden calculated that it would return only in 1992, which in fact it did.[5]

It is the parent body of the Perseid meteor shower, perhaps the best known shower and among the most reliable in performance.[9]

The comet's perihelion is just under that of Earth, while its aphelion is just over that of Pluto. An unusual aspect of its orbit is that it was recently captured into a 1:11 orbital resonance with Jupiter; it completes one orbit for every 11 of Jupiter.[5] It was the first comet in a retrograde orbit to be found in a resonance.[5] In principle this would mean that its proper long-term average period would be 130.48 years, as it librates about the resonance. Over the short term, between epochs 1737 and 2126 the orbital period varies between 128 and 136 years.[2] However, it only entered this resonance about 1000 years ago, and will probably exit the resonance in several thousand years.[5]

Threat to Earth

Sun · Earth · Jupiter · Saturn · Uranus · 109P/Swift–Tuttle

The comet is on an orbit that makes repeated close approaches to the Earth-Moon system,[5] and has an Earth-MOID (Minimum orbit intersection distance) of 0.0009 AU (130,000 km; 84,000 mi).[1] Upon its September 1992 rediscovery, the comet's date of perihelion passage was off from the 1973 prediction by 17 days.[10] It was then noticed that if its next perihelion passage (July 2126) was also off by another 15 days (July 26), the comet could impact the Earth on August 14, 2126 (IAUC 5636: 1992t).[11] Given the size of the nucleus of Swift–Tuttle, this was of some concern. This prompted amateur astronomer and writer Gary W. Kronk to search for previous apparitions of this comet. He found the comet was most likely observed by the Chinese in 69 BC and AD 188,[12] which was quickly confirmed by Brian Marsden and added to the list of perihelion passages at the Minor Planet Center.[2] This information and subsequent observations have led to recalculation of its orbit, which indicates the comet's orbit is sufficiently stable that there is absolutely no threat over the next two thousand years.[10] It is now known that the comet will pass 0.153 AU (22.9 million km; 14.2 million mi) from Earth on August 5, 2126.[1][lower-alpha 2] and within 0.147 AU (22.0 million km; 13.7 million mi) from Earth on August 24, 2261.[4]

A close encounter with Earth is predicted for the comet's return to the inner Solar System in the year 3044, with the closest approach estimated to be one million miles (1,600,000 km; 0.011 AU).[13] Another close encounter is predicted for the year 4479, around Sept. 15; the close approach is estimated to be less than 0.05 AU, with a probability of impact of 1 in a million.[5] Subsequent to 4479, the orbital evolution of the comet is more difficult to predict; the probability of Earth impact per orbit is estimated as 2×10−8 (0.000002%).[5]

Comet Swift–Tuttle is by far the largest near-Earth object (Apollo or Aten asteroid or short-period comet) to cross Earth's orbit and make repeated close approaches to Earth.[14] With a relative velocity of 60 km/s,[15][16] an Earth impact would have an estimated energy of ~27 times that of the Cretaceous–Paleogene impactor.[17] The comet has been described as "the single most dangerous object known to humanity".[16] In 1996, the long-term possibility of Comet Swift–Tuttle impacting Earth was compared to 433 Eros and about 3000 other kilometer-sized objects of concern.[18]

Notes

- v = 42.1219 √1/r − 0.5/a, where r is the distance from the Sun, and a is the semimajor axis.

- The 3-sigma uncertainty in the comet's closest approach to Earth on 5 August 2126 is about ±10 thousand km.

References

- "JPL Small-Body Database Browser: 109P/Swift–Tuttle" (last observation: 1995-03-29). Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Retrieved 2011-05-09.

- "109P/Swift-Tuttle Orbit". Minor Planet Center. Retrieved 2014-06-17.

- Syuichi Nakano (1999-11-18). "109P/Swift–Tuttle (NK 798)". OAA Computing and Minor Planet Sections. Retrieved 2011-05-09.

- Yau, K.; Yeomans, D.; Weissman, P. (1994). "The past and future motion of Comet P/Swift-Tuttle". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 266 (2): 305–316. Bibcode:1994MNRAS.266..305Y. doi:10.1093/mnras/266.2.305.

- Chambers, J. E. (1995). "The long-term dynamical evolution of Comet Swift–Tuttle". Icarus. Academic Press. 114 (2): 372–386. Bibcode:1995Icar..114..372C. doi:10.1006/icar.1995.1069.

- Levy, David H. (2008). David Levy's Guide to Observing Meteor Showers. Cambridge University Press. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-521-69691-3.

- Britt, Robert (2005-08-11). "Top 10 Perseid Meteor Shower Facts". Space.com. Retrieved 2009-08-10.

- Gary W. Kronk (1999). "109P/1737 N1". Cometography. 1. pp. 400–2.

- Bedient, John. "AMS Meteor Showers page", American Meteor Society, 20 June 2010. Retrieved 2010-7-31.

- Stephens, Sally (1993). "on Swift–Tuttle's possible collision". Astronomical Society of the Pacific. Archived from the original on 2012-05-25. Retrieved 2008-08-25.

- Marsden, Brian G. (1992-10-15). "IAUC 5636: Periodic Comet Swift–Tuttle (1992t)". Central Bureau for Astronomical Telegrams. Retrieved 2009-06-19.

- Marsden, Brian G. (1992-12-05). "IAUC 5670: Periodic Comet Swift–Tuttle (1992t)". Central Bureau for Astronomical Telegrams. Retrieved 2009-06-19.

- https://astrosociety.org/edu/publications/tnl/23/23.html

- "JPL Small-Body Database Search Engine: q < 1 (au) and period < 200 (years)". JPL Solar System Dynamics. Retrieved 24 July 2020.

- Weissman, Paul R. (August 2006), Milani, A.; Valsecchi, G.B.; Vokrouhlicky, D. (eds.), "The cometary impactor flux at the Earth", Proceedings of the International Astronomical Union, Near Earth Objects, our Celestial Neighbors: Opportunity and Risk; IAU Symposium No. 236, 2 (s236): 441–450, doi:10.1017/S1743921307003559

- Verschuur, Gerrit L. (1997). Impact!: the threat of comets and asteroids. Oxford University Press. pp. 256 (see p. 116). ISBN 978-0-19-511919-0.

- This calculation can be carried out in the manner given by Weissman for Comet Hale–Bopp, as follows: A radius of 13.5 km and an estimated density of 0.6 g/cm3 gives a cometary mass of 6.2×1018 g. An encounter velocity of 60 km/s yields an impact velocity of 61 km/s, giving an impact energy of 1.15×1032 ergs, or 2.75×109 megatons, about 27.5 times the estimated energy of the K–T impact event.

- Browne, Malcolm W. "Mathematicians Say Asteroid May Hit Earth in a Million Years". Retrieved 2018-11-16.

External links

- 109P/Swift-Tuttle at the Minor Planet Center's Database

- 109P/Swift–Tuttle at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory's Small-Body Database

- NASA Astronomy Picture of the Day: Periodic Comet Swift–Tuttle (19 February 1996)

| Numbered comets | ||

|---|---|---|

| Previous 108P/Ciffreo |

Comet Swift–Tuttle | Next 110P/Hartley |