433 Eros

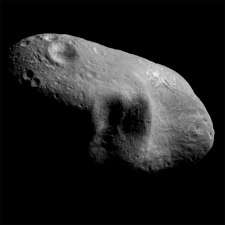

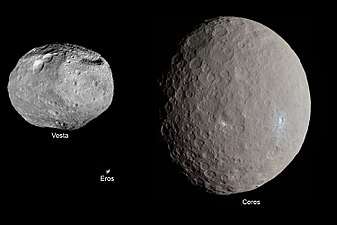

Eros (minor planet designation: 433 Eros), provisional designation 1898 DQ, is a stony and elongated asteroid of the Amor group and the first discovered and second-largest near-Earth object with a mean diameter of approximately 16.8 kilometers. Visited by the NEAR Shoemaker space probe in 1998, it became the first asteroid ever studied from orbit.

.jpg) Eros [lower-alpha 1] | |

| Discovery [1] | |

|---|---|

| Discovered by | G. Witt |

| Discovery site | Berlin Urania Obs. |

| Discovery date | 13 August 1898 |

| Designations | |

| (433) Eros | |

| Pronunciation | /ˈɪərɒs/[2] |

Named after | Eros (Greek mythology)[3] |

| |

| Adjectives | Erotian /ɛˈroʊʃ(i)ən/ |

| Orbital characteristics [1] | |

| Epoch 4 September 2017 (JD 2458000.5) | |

| Uncertainty parameter 0 | |

| Observation arc | 53.89 yr (19,683 days) |

| Aphelion | 1.7825 AU |

| Perihelion | 1.1334 AU |

| 1.4579 AU | |

| Eccentricity | 0.2226 |

| 1.76 yr (643 days) | |

| 71.280° | |

| 0° 33m 35.64s / day | |

| Inclination | 10.828° |

| 304.32° | |

| 178.82° | |

| Earth MOID | 0.1505 AU (58.6 LD) |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Dimensions | |

| Mass | (6.687±0.003)×1015 kg[4] |

Mean density | 2.67±0.03 g/cm3[1][4] |

| 5.270 h[1] | |

| 0.25±0.06[1] | |

| 7.0–15[6] | |

| 11.16[1] | |

The eccentric asteroid was discovered by German astronomer Carl Gustav Witt at the Berlin Observatory on 13 August 1898, and later named after Eros, a god from Greek mythology; the son of Aphrodite who is identified with the planet Venus.[3]

History

Discovery

Eros was discovered on 13 August 1898 by Carl Gustav Witt at Berlin Urania Observatory and Auguste Charlois at Nice Observatory.[7] Witt was taking a two-hour exposure of Beta Aquarii to secure astrometric positions of asteroid 185 Eunike.[8]

Later studies

During the opposition of 1900–1901, a worldwide program was launched to make parallax measurements of Eros to determine the solar parallax (or distance to the Sun), with the results published in 1910 by Arthur Hinks of Cambridge.[9] A similar program was then carried out, during a closer approach, in 1930–1931 by Harold Spencer Jones.[10] The value of the Astronomical Unit (roughly the Earth-Sun distance) obtained by this program was considered definitive until 1968, when radar and dynamical parallax methods started producing more precise measurements.

Eros was the first asteroid detected by the Arecibo Observatory's radar system.[11][12]

Eros was one of the first asteroids visited by a spacecraft, the first one orbited, and the first one soft-landed on. NASA spacecraft NEAR Shoemaker entered orbit around Eros in 2000, and landed in 2001.

Mars-crosser

Eros is a Mars-crosser asteroid, the first known to come within the orbit of Mars. Objects in such an orbit can remain there for only a few hundred million years before the orbit is perturbed by gravitational interactions. Dynamical integrations suggest that Eros may evolve into an Earth-crosser within as short an interval as two million years, and has a roughly 50% chance of doing so over a time scale of 108–109 years.[13] It is a potential Earth impactor,[13] about five times larger than the impactor that created Chicxulub crater and led to the extinction of the dinosaurs.[lower-alpha 2]

NEAR Shoemaker

The NEAR Shoemaker probe visited Eros twice, first with a 1998 flyby, and then by orbiting it in 2000 when it extensively photographed its surface. On 12 February 2001, at the end of its mission, it landed on the asteroid's surface using its maneuvering jets.

This was the first time a Near Earth asteroid was closely visited by a spacecraft.[15]

Animation of NEAR Shoemaker trajectory from 19 February 1996 to 12 February 2001.

Animation of NEAR Shoemaker trajectory from 19 February 1996 to 12 February 2001.

NEAR Shoemaker; 433 Eros; Earth; 253 Mathilde ; Sun. Animation of NEAR Shoemaker's trajectory around 433 Eros from 1 April 2000 to 12 February 2001.

Animation of NEAR Shoemaker's trajectory around 433 Eros from 1 April 2000 to 12 February 2001.

NEAR Shoemaker · 433 Eros.

Physical characteristics

Surface gravity depends on the distance from a spot on the surface to the center of a body's mass. Eros's surface gravity varies greatly because Eros is not a sphere but an elongated peanut-shaped (or potato- or shoe-shaped) object. The daytime temperature on Eros can reach about 100 °C (373 K) at perihelion. Nighttime measurements fall near −150 °C (123 K). Eros's density is 2.67 g/cm3, about the same as the density of Earth's crust. It rotates once every 5.27 hours.

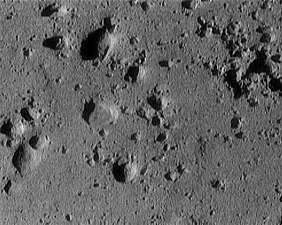

NEAR scientists have found that most of the larger rocks strewn across Eros were ejected from a single crater in an impact approximately 1 billion years ago.[16] (The crater involved was proposed to be named "Shoemaker", but is not recognized as such by the International Astronomical Union (IAU), and has been formally designated Charlois Regio.) This event may also be responsible for the 40 percent of the Erotian surface that is devoid of craters smaller than 0.5 kilometers across. It was originally thought that the debris thrown up by the collision filled in the smaller craters. An analysis of crater densities over the surface indicates that the areas with lower crater density are within 9 kilometers of the impact point. Some of the lower density areas were found on the opposite side of the asteroid but still within 9 kilometers.[17]

It is theorized that seismic shockwaves propagate through the asteroid, shaking smaller craters into rubble. Since Eros is irregularly shaped, parts of the surface antipodal to the point of impact can be within 9 kilometres of the impact point (measured in a straight line through the asteroid) even though some intervening parts of the surface are more than 9 kilometres away in straight-line distance. A suitable analogy would be the distance from the top centre of a bun to the bottom centre as compared to the distance from the top centre to a point on the bun's circumference: top-to-bottom is a longer distance than top-to-periphery when measured along the surface but shorter than it in direct straight-line terms.[17]

Compression from the same impact is believed to have created the thrust fault Hinks Dorsum.[18]

Data from the Near Earth Asteroid Rendezvous spacecraft collected on Eros in December 1998 suggests that it could contain 20 billion tonnes of aluminum and similar amounts of metals that are rare on Earth, such as gold and platinum.[19]

Visibility from Earth

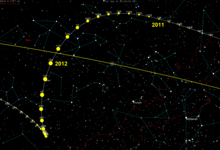

On 31 January 2012, Eros passed Earth at 0.17867 AU (26,729,000 km; 16,608,000 mi),[20][21] about 70 times the distance to the Moon, with a visual magnitude of +8.1.[22] During rare oppositions, every 81 years, such as in 1975 and 2056, Eros can reach a magnitude of +7.0,[6] which is brighter than Neptune and brighter than any main-belt asteroid except 1 Ceres, 4 Vesta and, rarely, 2 Pallas and 7 Iris. Under this condition, the asteroid actually appears to stop, but unlike the normal condition for a body in heliocentric conjunction with Earth, its retrograde motion is very small. For example, in January and February 2137, it moves retrograde only 34 minutes in right ascension.[1]

Gallery

Animation of the rotation of Eros

Animation of the rotation of Eros View from one end of Eros across the gouge on its side towards the opposite end

View from one end of Eros across the gouge on its side towards the opposite end First mosaic image of Eros taken from an orbiting spacecraft

First mosaic image of Eros taken from an orbiting spacecraft Mosaic image of Eros

Mosaic image of Eros At 4.8 km (3.0 mi) across, the crater Psyche is Eros's second largest.

At 4.8 km (3.0 mi) across, the crater Psyche is Eros's second largest. Regolith of Eros, seen during NEAR's descent; area shown is about 12 meters (40 feet) across

Regolith of Eros, seen during NEAR's descent; area shown is about 12 meters (40 feet) across- Orbital diagram of Eros with locations on 7 May 2013

Orbital diagram of Eros with locations on 1 January 2018

Orbital diagram of Eros with locations on 1 January 2018

Six different views of Eros in approximate natural color from NEAR-Shoemaker in February 2000

Six different views of Eros in approximate natural color from NEAR-Shoemaker in February 2000 Stereo image of Eros

Stereo image of Eros

Notes

- A composite image of the north polar region, with the craters Psyche above and Himeros below. The long ridge Hinks Dorsum, believed to be a thrust fault, can be seen snaking diagonally between them. The smaller crater in the foreground is Narcissus (Watters, 2011)

- Ratio of mean diameters is 16.84 km/~10 km; the volume ratio is approximately 4.8 (cubed value).

References

- "JPL Small-Body Database Browser: 433 Eros (1898 DQ)" (2017-06-04 last obs.). Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Retrieved 16 August 2017.

- "Eros". Oxford English Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. September 2005. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Schmadel, Lutz D. (2007). "(433) Eros". Dictionary of Minor Planet Names – (433) Eros. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. p. 50. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-29925-7_434. ISBN 978-3-540-00238-3.

- Yeomans, D. K.; Antreasian, P. G.; Barriot, J.-P.; Chesley, S. R.; Dunham, D. W.; Farquhar, R. W.; et al. (September 2000). "Radio Science Results During the NEAR-Shoemaker Spacecraft Rendezvous with Eros". Science. 289 (5487): 2085–2088. Bibcode:2000Sci...289.2085Y. doi:10.1126/science.289.5487.2085. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 11000104.

- Jim Baer (2008). "Recent Asteroid Mass Determinations". Personal Website. Archived from the original on 29 January 2009. Retrieved 11 December 2008.

- "NEODys (433) Eros Ephemerides for 2137". Department of Mathematics, University of Pisa, Italy. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- Scholl, Hans; Schmadel, Lutz D. (2002). "Discovery Circumstances of the First Near-Earth Asteroid (433) Eros". Acta Historica Astronomiae. 15: 210–220. Bibcode:2002AcHA...15..210S.

- Yeomans, Donald K.; Asteroid 433 Eros: The Target Body of the NEAR Mission Archived 2007-09-28 at the Wayback Machine, Jet Propulsion Laboratory/California Institute of Technology.

- Hinks, Arthur R. (1909). "Solar Parallax Papers No. 7: The General Solution from the Photographic Right Ascensions of Eros, at the Opposition of 1900" (PDF). Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 69 (7): 544–67. Bibcode:1909MNRAS..69..544H. doi:10.1093/mnras/69.7.544.

- Jones, H. Spencer (1941). "The Solar Parallax and the Mass of the Moon from Observations of Eros at the Opposition of 1931". Mem. Roy. Astron. Soc. 66: 11–66.

- Butrica, Andrew J. (1996). To see the unseen: a history of planetary radar astronomy (2nd ed.). Washington, DC: National Aeronautics and Space Administration. p. 224. ISBN 978-0160485787.

- "Introduction to Asteroid Radar Astronomy". UCLA. Retrieved 19 May 2014.

- Michel, Patrick; Farinella, Paolo; Froeschlé, Christiane (25 April 1996). "The orbital evolution of the asteroid Eros and implications for collision with the Earth". Nature. 380 (6576): 689–691. Bibcode:1996Natur.380..689M. doi:10.1038/380689a0.

- Asimov, Isaac (1988). The asteroids (A Gareth Stevens children's books ed.). Milwaukee: G. Stevens Pub. ISBN 978-1555323783. OCLC 17301161.

- "The End is Near | DiscoverMagazine.com". Discover Magazine. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- Thomas, P. C.; Veverka, J.; Robinson, M. S.; Murchie, S. (27 September 2001). "Shoemaker crater as the source of most ejecta blocks on the asteroid 433 Eros". Nature. 413 (6854): 394–396. Bibcode:2001Natur.413..394T. doi:10.1038/35096513. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 11574880.

- Thomas, P. C.; Robinson, M. S. (21 July 2005). "Seismic resurfacing by a single impact on the asteroid 433 Eros". Nature. 436 (7049): 366–369. Bibcode:2005Natur.436..366T. doi:10.1038/nature03855. PMID 16034412.

- Watters, T. R.; Thomas, P. C.; Robinson, M. S. (2011). "Thrust faults and the near-surface strength of asteroid 433 Eros". Geophysical Research Letters. 38 (2): L02202. Bibcode:2011GeoRL..38.2202W. doi:10.1029/2010GL045302. ISSN 0094-8276.

- "Gold rush in space?". BBC News. Retrieved 13 December 2014.

- "JPL Close-Approach Data: 433 Eros (1898 DQ)" (2011-11-13 last obs). Retrieved 14 November 2011.

- "NEODyS-2 Close Approaches for (433) Eros". Near Earth Objects – Dynamic Site. Retrieved 14 November 2011.

- "AstDys (433) Eros Ephemerides for 2012". Department of Mathematics, University of Pisa, Italy. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

Further reading

- Clark, C. S.; Clark, P. E. (13–17 March 2006). Using Boundary-based Mapping Projections to Reveal Patterns in Depositional and Erosional Features on 433 Eros. 37th Annual Lunar and Planetary Science Conference. League City, Texas. p. 1189. Bibcode:2006LPI....37.1189C. Abstract no.1189.

- Riner, M. A.; et al. (November 2008). "Global survey of color variations on 433 Eros: Implications for regolith processes and asteroid environments". Icarus. 198 (1): 67–76. Bibcode:2008Icar..198...67R. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2008.07.007.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to (433) Eros. |

- NEAR Shoemaker spacecraft

- NEAR image of the day archive

- Movie: NEAR Shoemaker spacecraft landing

- The Eros Project (OrbDev's attempts at litigation over their property claim)

- 3D VRML 433 Eros Model

- 3D shape model of Eros (requires WebGL)

- NEODys (saved output file from 2007) showing distance and magnitude Ephemerides for Eros during rare oppositions

- The Chicxulub Debate In relation to the K-T extinction.

- Dearborn Observatory Records, Northwestern University Archives, Evanston, Illinois Notations as to historical archived work on asteroid 433 Eros.

- Eros at Opposition in 2012 (Royal Astronomical Society of New Zealand)

- NEAR database by ASU (Image search) (Example)

- Eros nomenclature and Eros map with feature names from the USGS planetary nomenclature page

- 433 Eros at NeoDyS-2, Near Earth Objects—Dynamic Site

- Ephemeris · Obs prediction · Orbital info · MOID · Proper elements · Obs info · Close · Physical info · NEOCC

- 433 Eros at AstDyS-2, Asteroids—Dynamic Site

- 433 Eros at the JPL Small-Body Database