Sorbs (tribe)

The Sorbs, also known as White Serbs in Serbian historiography, were an Early Slavic tribe located in present-day Saxony and Thuringia, part of the Wends. In the 7th century, the tribe was part of Samo's Empire. The tribe is last mentioned in the late 10th century, but its descendants are an ethnic group of Sorbs and Serbs.

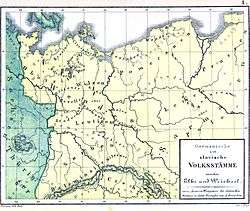

_Das_Siedlungsgebiet_der_Sorben_vom_7._bis_11._Jahrhundert_in_Mitteldeutschland.jpg)

Etymology

They are mentioned between the 6th and 10th century as Cervetiis (Servetiis), gentis (S)urbiorum, Suurbi, Sorabi, Soraborum, Sorabos, Surpe, Sorabici, Sorabiet, Sarbin, Swrbjn, Servians, Zribia, and Suurbelant.[1] While some consider their ethnonym *Sŕbъ (plur. *Sŕby) to be of Iranian-Sarmatian origin, other argue a derivation from Proto-Slavic language with a appellative meaning of a "family kinship" and "alliance".[1][2][3]

History

7th century

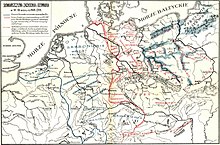

Their origin is unclear. According to the opinion of some historians and archaeologists, the tribe arrived from the Middle Danube valley in the beginning of the 7th century, they originally lived between Saale and Elbe river, and only later since the 10th century their ethnonym was transferred to the Luzici, Milceni and other tribes of Sukow-Dziedzice culture of Tornovo group for which is argued to have been present already from the 6th century.[4] However, it is considered to be completely unfounded by other scholars.[5]

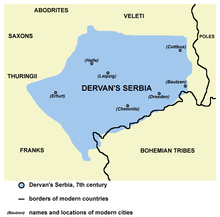

It is considered that their earliest mention is at least from the 6th century or earlier by Vibius Sequester, who recorded Cervetiis (Servetiis) living on the other part of the river Elbe which divided them from the Suevi (Albis Germaniae Suevos a Cerveciis dividiit).[1][6][7][8][9][10][11][12] According to Lubor Niederle, the Serbian district was located somewhere between Magdeburg and Lusatia, and was later mentioned by the Ottonians as Ciervisti, Zerbisti, and Kirvisti.[13] Their area of settlement possibly also included part of Chebsko, the northwestern edge of the Czech Republic.[8] The information is in accordance with the Frankish 7th-century Chronicle of Fredegar according to which the Surbi lived in the Saale-Elbe valley, having settled in the Thuringian part of Francia at least since the second-half of the 6th century and were vassals of Merovingian dynasty.[8][14][15] The Saale-Elbe line marked the approximate limit of Slavic westward migration.[16] Fredegar recounts that under the leadership of dux (duke) Dervan (Dervanus dux gente Surbiorum que ex genere Sclavinorum), they joined the Slavic tribal union of Samo, after Samo's decisive victory against Frankish King Dagobert I in 631.[14][15] Afterwards, these Slavic tribes continuously raided Thuringia.[14] The fate of the tribes after Samo's death and dissolution of the union in 658 is undetermined, but it is considered that subsequently returned to Frankish vassalage.[17]

According to 10th-century source De Administrando Imperio, writing on the Serbs and their lands previously dwelt in, they lived "since the beginning" in the region called by them as Boiki (Bohemia) which was a neighbor to Francia, and when two brothers succeeded their father, one of them migrated with half of the people to the Balkans during the rule of Heraclius in the first half of the 7th century.[18][19] According to some scholars, the White Serbian Unknown Archon who led them to the Balkans was most likely a son, brother or other relative of Dervan.[20][21][22][23]

8th century

In 782, the Sorbs, inhabiting the region between the Elbe and Saale, plundered Thuringia and Saxony.[24] Charlemagne sent Adalgis, Worad and Geilo into Saxony, aimed at attacking the Sorbs, however, they met with rebel Saxons who destroyed them.[25]

In 789, Charlemagne launched a campaign against the Wiltzi; after reaching the Elbe, he went further and successfully "subjected the Slavs".[26] His army also included the Slavic Sorbs and Obotrites, under Witzan.[26] The army reached Dragovit, who surrendered, followed by other Slavic magnates and chieftains who submitted to Charlemagne.[26]

9th century

The Sorbs ended their partial vassalage to the Franks (the Carolingian Empire) and revolted, invading Austrasia; Charles the Younger launched a campaign against the Slavs in Bohemia in 805, killing their dux, Lecho, and then proceeded crossing the Saale with his army and killed rex (king) Melito (or "Miliduoch") of the Sorabi or Siurbis, near modern-day Weißenfels, in 806.[27][28][29] The region was laid to waste, upon which the other Slavic chieftains submitted and gave hostages.[30][31] The rebellious Sorbs were compelled in 816 to renew their oaths of submission.[29][32]

In May 826, at a meeting at Ingelheim, Cedrag of the Obotrites and Tunglo of the Sorbs were accused of malpractices; they were ordered to appear in October, after Tunglo surrendered his son as hostage and was allowed to return home.[33] The Franks had, sometime before the 830s, established the Sorbian March, comprising eastern Thuringia, in easternmost East Francia.

In 839, the Saxons fought "the Sorabos, called Colodici" at Kesigesburch and won the battle, managing to kill their king Cimusclo (or "Czimislav"), with Kesigesburch and eleven forts being captured.[29][34] The Sorbs were forced to pay tribute and forfeited territory to the Franks.[34] The Sorbian tribe of Colodici was furthermore mentioned in 973 (Coledizi pagus, Cholidici), in 975 (Colidiki), and 1015 (Colidici locus).[35]

The mid-9th century Bavarian Geographer mentioned the Surbi having 50 civitates (Iuxta illos est regio, que vocatur Surbi, in qua regione plures sunt, que habent civitates L).[36][1] Alfred the Great in his Geography of Europe (888–893) relying on Orosius, recorded the Servians; "To the north-east of the Moravians are the Dalamensae; east of the Dalamensians are the Horithi, and north of the Dalamensians are the Servians; to the west also are the Silesians. To the north of the Horiti is Mazovia, and north of Mazovia are the Sarmatians, as far as the Riphean Mountains".[37]

It is considered that in the second-half of the 9th century, Svatopluk I of Moravia (r. 871–894) may have incorporated the Sorbs into Great Moravia.[16]

10th century

The Arab historians and geographers Al-Masudi and Al-Bakri (10th and 11th century) writing on the Saqaliba mentioned the Sarbin or Sernin living between the Germans and the Moravians, a "Slavic people much feared for reasons that it would take too long to explain and whose deeds would need much too detailed an account. They have no particular religious affiliation". They, like other Slavs, "have the custom of burning themselves alive when a king or chieftain dies. They also immolate his horses".[38][39][40] In the Hebrew book Josippon (10th century) are listed four Slavic ethnic names from Venice to Saxony; Mwr.wh (Moravians), Krw.tj (Croats), Swrbjn (Sorbs), Lwcnj (Lučané or Lusatians).[41]

Between 932 and 963 the Sorbs lost their independence.[42] Henry the Fowler had subjected the Stodorane in 928, and in the following year imposed overlordship on the Obotrites and Veletians, and strengthened the grip on the Sorbs.[43] Bishop Boso of St. Emmeram (d. 970), a Slav-speaker, had considerable success in Christianizing the Sorbs.[44]

In the 10th century the region came under the influence of the Duchy of Saxony, starting with the 928 eastern campaigns of King Henry the Fowler, who conquered the Sorbs and Milceni (Upper Lusatia) by 932. Gero II, Margrave of the Saxon Eastern March, reconquered Lusatia the following year and, in 939, murdered 30 Sorbian princes during a feast. As a result, many Sorbian uprisings followed. The March of Lusatia was established in 965, remaining part of the Holy Roman Empire, while the adjacent Northern March was again lost in the Slavic uprising of 983. The later Upper Lusatian region of the Milceni lands up to the Silesian border at the Kwisa river at first was part of the Margraviate of Meissen under Margrave Eckard I. A reconstructed castle, at Raddusch in Lower Lusatia, is the sole physical remnant from this early period. These are the last mentions of the tribe.

Aftermath

During the reign of Boleslaw I of Poland in 1002–18, three Polish-German wars were waged which caused Lusatia to come under the domination of new rulers. In 1018, on the strength of peace in Bautzen, Lusatia became a part of Poland; however, it returned to German rule before 1031. At the same time the Kingdom of Poland raised claims to the Lusatian lands and upon the death of Emperor Otto III in 1002, Margrave Gero II lost Lusatia to the Polish Duke Boleslaw I, who took the region in his conquests. After the 1018 Peace of Bautzen, Lusatia became part of his territory, however Germans and Poles continued struggling for administration of the region. It was regained in a 1031 campaign by Emperor Conrad II in favour of the Saxon German rulers of the Meissen House of Wettin and the Ascanian margraves of Brandenburg, who purchased the March of (Lower) Lusatia in 1303. In 1367 the Brandenburg elector Otto V of Wittelsbach finally sold Lower Lusatia to Emperor and Bohemian King Charles IV and it was incorporated into the Kingdom of Bohemia.

From the 11th to the 15th century, agriculture in Lusatia developed and colonization by Frankish, Flemish and Saxon settlers intensified. In 1327 the first prohibitions on using Sorbian in Altenburg, Zwickau and Leipzig appeared.

References

- Łuczyński, Michal (2017). "„Geograf Bawarski" — nowe odczytania" ["Bavarian Geographer" — New readings]. Polonica (in Polish). XXXVII (37): 71. doi:10.17651/POLON.37.9. Retrieved 4 August 2020.

- Rudnicki, Mikołaj (1959). Prasłowiańszczyzna, Lechia-Polska (in Polish). Państwowe wydawn. naukowe, Oddzia ︢w Poznaniu. p. 182.

- Popowska-Taborska, Hanna (1993). "Ślady etnonimów słowiańskich z elementem obcym w nazewnictwie polskim". Acta Universitatis Lodziensis. Folia Linguistica (in Polish). 27: 225–230. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- Sedov, Valentin Vasilyevich (2013) [1995]. Славяне в раннем Средневековье [Sloveni u ranom srednjem veku (Slavs in Early Middle Ages)]. Novi Sad: Akademska knjiga. pp. 191–205, 458–466. ISBN 978-86-6263-026-1.

- Schuster-Šewc, Heinz. "Порекло и историја етнонима Serb "Лужички Србин"". rastko.rs (in Serbian). Translated by Petrović, Tanja. Пројекат Растко - Будишин.

- Fischer, Adam (1932). Etnografja Słowiańska: Łużyczanie (in Polish). Ksia̧żnica-Atlas. p. 46.

Najdawniejszą wzmiankę o plemionach łużyckich mamy u Wibia Sequestra (VI w.), że „Albis Suevos a Cervetiis dividit". Następnie wiemy, że w latach 623–631 istniało Księstwo łużyckie nad Salą, a wedle Fredegara...

- Małowist, Marian (1954). Materiały źródłowe do historii Polski epoki feudalnej (in Polish). Państwowe Wydawn. Naukowe. p. 47.

Albis Germaniae Suevos a Cervetiis dividit. (Rzeka) Łaba oddziela Swewów1 od Serbów... Swewowie oznaczają tu znany lud germański, który w początkach n . e . mieszkał nad Łabą, a następnie...

- Simek, Emanuel (1955). Chebsko V Staré Dobe: Dnesní Nejzápadnejsi Slovanské Území (in Czech). Vydává Masarykova Universita v Brne. pp. 47, 269, 271, 274.

O Srbech máme zachován první historický záznam ze VI. století u Vibia Sequestra, který praví, že Labe dělí v GermaniinSrby od Suevů65. Tím ovšem nemusí být řečeno, že v končinách severně od českých hor nemohli býti Srbové již i za Labem (západně od Labe), neboť nevíme, koho Vibius Sequester svými Suevy mínil. Ať již tomu bylo jakkoli, víme bezpečně ze zpráv kroniky Fredegarovy, že Srbové měli celou oblast mezi Labem a Sálou osídlenu již delší dobu před založením říše Samovy66, tedy nejméně již v druhé polovici VI. století67. Jejich kníže Drevan se osvobodil od nadvlády francké a připojil se někdy kolem roku 630 se svou državou k říši Samově68. V následujících letech podnikali Srbové opětovně vpády přes Sálu do Durinska 69... 67 Schwarz, ON 48, dospěl k závěru, že se země mezi Labem a Sálou stala srbskou asi r. 595 a kolem roku 600 že bylo slovanské stěhování do končin západně od Labe určitě již skončeno; R. Fischer, GSl V. 58, Heimatbildung XVIII. 298, ON Falk. 59, NK 69 datuje příchod Slovanů na Chebsko do druhé polovice VI. století, G. Fischer(ová), Flurnamen 218, do VI. století. Chebský historik Sieg1 dospěl v posledním svém souhrnném díle o dějinách Chebska Eger u. Egerland 4 k závěru, že Slované (myslil na Srby) přišli do Chebska již kolem roku 490, tedy před koncem V. století.

- Sułowski, Zygmunt (1961). "Migracja Słowian na zachód w pierwszym tysiącleciu n. e." Roczniki Historyczne (in Polish). 27: 50–52. Retrieved 4 August 2020.

- Tyszkiewicz, Lech A. (1990). Słowianie w historiografii antycznej do połowy VI wieku (in Polish). Wydawn. Uniwersytetu Wrocławskiego. p. 124. ISBN 978-83-229-0421-3.

...Germaniae Suevos a Cervetiis dividit mergitur in oceanum”. Według Szafarzyka, który odrzucił emendację Oberlina Cervetiis na Cheruscis, zagadkowy lud Cervetti to nikt inny, jak tylko Serbowie połabscy.

- Dulinicz, Marek (2001). Kształtowanie się Słowiańszczyzny Północno-Zachodniej: studium archeologiczne (in Polish). Instytut Archeologii i Etnologii Polskiej Akademii Nauk. p. 17. ISBN 978-83-85463-89-4.

- Moczulski, Leszek (2007). Narodziny Międzymorza: ukształtowanie ojczyzn, powstanie państw oraz układy geopolityczne wschodniej części Europy w późnej starożytności i we wczesnym średniowieczu (in Polish). Bellona. pp. 335–336.

Tak jest ze wzmianką Vibiusa Sequestra, pisarza z przełomu IV—V w., którą niektórzy badacze uznali za najwcześniejszą informację o Słowianach na Polabiu: Albis Germaniae Suevon a Cervetiis dividit (Vibii Sequestris, De fluminibus, fontibus, lacubus, memoribus, paludibus, montibus, gentibus, per litteras, wyd. Al. Riese, Geographi latini minores, Heilbronn 1878). Jeśli początek nazwy Cerve-tiis odpowiadał Serbe — chodziło o Serbów, jeśli Cherue — byli to Cheruskowie, choć nie można wykluczyć, że pod tą nazwą kryje się jeszcze inny lud (por. G. Labuda, Fragmenty dziejów Słowiańszczyzny Zachodniej, t. 1, Poznań 1960, s. 91; H. Lowmiański, Początki Polski..., t. II, Warszawa 1964, s. 296; J. Strzelczyk, Vibius Sequester [w:] Slownik Starożytności Słowiańskich, t. VI, Wroclaw 1977, s. 414). Pierwsza ewentualność sygeruje, że zachodnia eks-pansja Słowian rozpoczęta się kilka pokoleń wcześniej niż się obecnie przypuszcza, druga —że rozgraniczenie pomiędzy Cheruskami a Swebami (Gotonami przez Labę względnie Semnonami przez Soławę) uksztaltowało się — być może po klęsce Marboda — dalej na południowy wschód, niżby wynikało z Germanii Tacyta (patrz wyżej). Tyle tylko, że nie będzie to sytuacja z IV w. Istnienie styku serbsko-turyńskiego w początkach VII w. potwierdza Kronika Fredegara (Chronicarum quae dicuntw; Fredegari scholastici, wyd. B., Krusch, Monu-menta Gennaniae Bisiorka, Scriptores rerum Merovingicarum, t. II, Hannover 1888, s. 130); bylby on jednak późniejszy niż styk Franków ze Slowianami (Sldawami, Winklami) w Alpach i na osi Dunaju. Tyle tylko, te o takim styku możemy mówić dopiero w końcu VI w.

- Fomina, Z.Ye. (2016). "Славянская топонимия в современной Германии в лингвокультуроло-гическоми лингво-историческом аспек" [Slavonic Toponymy in Linguoculturological and Linguo-historical Aspects in Germany]. Современные лингвистические и методико-дидактические исследования (in Russian) (1 (12)): 30. Retrieved 4 August 2020.

Как следует из многотомного издания „Славянские древности“ (1953) известного чешского ученого Любора Нидерле, первым историческим известием о славянах на Эльбе является запись Вибия Секвестра «De fluminibus» (VI век), в которой об Эльбе говорится: «Albis Suevos a Cervetiis dividit». Cervetii означает здесь наименованиесербскогоокруга (pagus) на правом берегу Эльбы, между Магдебургом и Лужицами, который в позднейших грамотах Оттона I, Оттона II и Генриха II упоминается под терминомCiervisti, Zerbisti, Kirvisti,нынешний Цербст[8]. В тот период, как пишет Любор Нидерле, а именно в 782 году, началось большое, имевшее мировое значение, наступление германцев против сла-вян. ПерейдяЭльбу, славяне представляли большую опасность для империи Карла Вели-кого. Для того, чтобы создать какой-то порядок на востоке, Карл Великий в 805 году соз-дал так называемый limes Sorabicus, который должен был стать границей экономических (торговых) связеймежду германцами и славянами[8].

- Sigfried J. de Laet; Joachim Herrmann (1 January 1996). History of Humanity: From the seventh century B.C. to the seventh century A.D. UNESCO. pp. 282–284. ISBN 978-92-3-102812-0.

- Gerald Stone (2015). Slav Outposts in Central European History: The Wends, Sorbs and Kashubs. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 6. ISBN 978-1-4725-9211-8.

- Vlasto 1970, p. 142.

- Saskia Pronk-Tiethoff (2013). The Germanic loanwords in Proto-Slavic. Rodopi. pp. 68–69. ISBN 978-94-012-0984-7.

- Živković, Tibor (2002). Јужни Словени под византијском влашћу (600-1025). Belgrade: Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts. p. 198.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Živković, Tibor (2012). De conversione Croatorum et Serborum: A Lost Source. Belgrade: The Institute of History. pp. 152–185.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sava S. Vujić, Bogdan M. Basarić (1998). Severni Srbi (ne)zaboravljeni narod. Beograd. p. 40.

- Miloš S. Milojević (1872). Odlomci Istorije Srba i srpskih jugoslavenskih zemalja u Turskoj i Austriji. U državnoj štampariji. p. 1.

- Relja Novaković (1977). Odakle su Sebl dos̆il na Balkansko poluostrvo. Istorijski institut. p. 337.

- Kardaras, Georgios (2018). Florin Curta; Dušan Zupka (eds.). Byzantium and the Avars, 6th-9th Century AD: political, diplomatic and cultural relations. BRILL. p. 95. ISBN 978-90-04-38226-8.

- Verbruggen 1997, p. 21.

- Jim Bradbury (2 August 2004). The Routledge Companion to Medieval Warfare. Routledge. pp. 118–. ISBN 978-1-134-59847-2.

- Leif Inge Ree Petersen (1 August 2013). Siege Warfare and Military Organization in the Successor States (400-800 AD): Byzantium, the West and Islam. BRILL. pp. 749–750. ISBN 978-90-04-25446-6.

- Vickers, Robert H. (1894). History of Bohemia. Chicago: C. H. Sergel Company. p. 48.

- Gerard Labuda (2002). Fragmenty dziejów Słowiańszczyzny zachodniej. PTPN. ISBN 978-83-7063-337-0.

806: „Et inde post non multos dies [imperator] Aquasgrani veniens Karlum filium suum in terram Sclavorum, qui dicuntur Sorabi, qui sedent super Albim fluvium, cum exercitu misit; in qua expeditione Miliduoch Sclavorum dux interf ectus

- Henryk Łowmiański, O identyfikacji nazw Geografa bawarskiego, Studia Źródłoznawcze, t. III: 1958, s. 1–22; reed: w: Studia nad dziejami Słowiańszczyzny, Polski i Rusi w wiekach średnich, Wydawnictwo Naukowe Uniwersytetu im. Adama Mickiewicza, Poznań 1986, s. 151–181, ISSN 0554-8217

- Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, Vol. 9, Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, JSTOR (Organization), 1880, p. 224

- Verbruggen 1997, pp. 314-315.

- Bury 2011, p. 900.

- Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. 1880. p. 224.

- Janet Laughland Nelson (1 January 1991). The Annals of St-Bertin. Manchester University Press. pp. 48–. ISBN 978-0-7190-3425-1.

- Šafárik, Pavel Jozef (1837). Slowanské starožitnosti (in Slovak). Tiskem I. Spurného. p. 912.

- Pierre Riche (1 January 1993). The Carolingians: A Family Who Forged Europe. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 110–. ISBN 0-8122-1342-4.

- Ingram, James (1807). An Inaugural Lecture on the Utility of Anglo-Saxon Literatures to which is Added the Geography of Europe by King Alfred, Including His Account of the Discovery of the North Cape in the Ninth Century. University Press. p. 72.

- Faḍlān, Aḥmad Ibn (2012). Ibn Fadlan and the Land of Darkness: Arab Travellers in the Far North. Translated by Lunde, Paul; Stone, Caroline. Penguin. pp. 128, 200. ISBN 978-0-14-045507-6.

- Lewicki, Tadeusz (1949). "Świat słowiański w oczach pisarzy arabskich". Slavia Antiqua (in Polish). 2 (2): 321–388. Retrieved 4 August 2020.

- Janković, Đorđe (2001). "Slovenski i srpski pogrebni obred u pisanim izvorima i arheološka građa" [Slavic and Serbian Mortuary Ritual in Written Sources and Archaeological Material]. Journal of the Serbian Archaeological Society (in Serbian) (17): 128. Retrieved 4 August 2020.

- Łowmiański, Henryk (2004) [1964]. Nosić, Milan (ed.). Hrvatska pradomovina (Chorwacja Nadwiślańska in Początki Polski) [Croatian ancient homeland] (in Croatian). Translated by Kryżan-Stanojević, Barbara. Maveda. p. 84–86. OCLC 831099194.

- Vlasto 1970, p. 147.

- Vlasto 1970, p. 144.

- Vlasto 1970, p. 90.

- Secondary sources

- Vlasto, A. P. (1970). The Entry of the Slavs Into Christendom: An Introduction to the Medieval History of the Slavs. CUP Archive. pp. 142–147. ISBN 978-0-521-07459-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Verbruggen, J. F. (1997). The Art of Warfare in Western Europe During the Middle Ages: From the Eighth Century to 1340. Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 978-0-85115-570-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bury, J.B. (2011). The Cambridge Medieval History Series volumes 1-5. Plantagenet Publishing. GGKEY:G636GD76LW7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Primary sources

- Chronicle of Fredegar, 642

- Royal Frankish Annals, 829

- Bavarian Geographer, mid-9th-century

- Annales Fuldenses, 901