Veleti

The Veleti (German: Wieleten; Polish: Wieleci) or Wilzi(ans) (also Wiltzes; German: Wilzen) were a group of medieval Lechitic tribes within the territory of modern northeastern Germany, related to Polabian Slavs. In common with other Slavic groups between the Elbe and Oder Rivers, they were often described by Germanic sources as Wends. In the late 10th century, they were continued by the Lutici. In Einhard's Vita Karoli Magni, the Wilzi are said to refer to themselves as Welatabians.[1]

Confederacy of the Veleti | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6th century–10th century | |||||||||

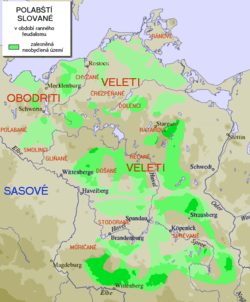

Grey: Former settlement area of the Polabian Slavs. Green: Uninhabited forest areas. Darker shade just indicates higher elevation. | |||||||||

| Capital | Unknown | ||||||||

| Common languages | Polabian language | ||||||||

| Religion | Slavic paganism | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy (Principality) | ||||||||

| Prince | |||||||||

• c. 740–? | Dragovit | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• Formed | 6th century | ||||||||

• Collapse of Veletian central rule | 798 | ||||||||

• Polabian tribes reorganized as the Lutician federation | 10th century | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||

Name

The name Veleti stems from the root vel- ('high, tall'). The Veleti were called by other names, probably given by their neighbours, such as Lutices, Ljutici, or Volki, Volčki. The latter means 'wolf', and the former probably 'fierce creature' based upon the comparison with the Russian form lyutyj zvěr.[2]

Veleti tribes

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

The first mention of a tribe named Veltae is founding Ptolemy's Geography where, writing in the second century, Ptolemy states in Book III, chapter V: "Back from the Ocean, near the Venedicus Bay [Baltic Sea], the Veltae dwell, above whom are the Ossi." The Bavarian Geographer's anonymous medieval document compiled in Regensburg in 830 contains a list of the tribes in Central Europe east of the Elbe. Among other tribes it also lists the Uuilci (Veleti), featuring 95 civitates.

The Veleti did not remain a unified tribe for long. Local tribes developed, the most important being: the Kissini (Kessiner, Chizzinen, Kyzziner) along the lower Warnow and Rostock, named after their capital Kessin; the Circipani (Zirzipanen) along the Trebel and Peene Rivers, with their capital believed to be Teterow and strongholds in Demmin and probably even Güstrow; the Tollenser east and south of the Peene along the Tollense River; and the Redarier south and east of the Tollensesee on the upper Havel. The Hevelli living in the Havel area and, though more unlikely, the Rujanes of Rugia might once have been part of the Veletians. Even the Leitha region of Lower Austria may have been named for a tribe of Veneti, the Leithi.

This political splitting of the Veleti probably occurred due to the size of the inhabited area, with settlements grouped around rivers and forts and separated by large strips of woodlands. Also, the Veletian king Dragowit had been defeated and made a vassal by Charlemagne in the only expedition into Slavic territory led by Charlemagne himself, in 798, causing the central Veletian rule to collapse. The Veleti were invaded by the Franks during their continuous expeditions into Obodrite lands, with the Obodrites being allies of the Franks against the Saxons. Einhard made these claims in "Vita Karoli Magni" (Life of Charles the Great), a biography of Charlemagne, King of the Franks.

After the 10th century, the Veleti disappeared from written records, and were replaced by the Lutici who at least in part continued the Veleti tradition.

See also

- Pomerania during the Early Middle Ages

- List of Medieval Slavic tribes

- Lutici

- Obotrites

References

- "Internet History Sourcebooks". www.fordham.edu.

- Sergent, Bernard (1991). "Ethnozoonymes indo-européens". Dialogues d'histoire ancienne. 17 (2): 24. doi:10.3406/dha.1991.1932.

- Christiansen, Erik (1997). The Northern Crusades. London: Penguin Books. p. 287. ISBN 0-14-026653-4.

- Herrmann, Joachim (1970). Die Slawen in Deutschland (in German). Berlin: Akademie-Verlag GmbH.

External links

- Dragowit, Fürst der Wilzen (in German)