Super 35

Super 35 (originally known as Superscope 235) is a motion picture film format that uses exactly the same film stock as standard 35 mm film, but puts a larger image frame on that stock by using the space normally reserved for the optical analog sound track.

History

Super 35 was revived from a similar Superscope variant known as Superscope 235, which was originally developed by the Tushinsky Brothers (who founded Superscope Inc. in 1954) for RKO in 1954. The first film to be shot in Superscope was Vera Cruz.[1]

When cameraman Joe Dunton[2] was preparing to shoot Dance Craze in 1982, he chose to revive the Superscope format by using a full silent-standard gate and slightly optically recentering the lens port (to adjust for the inclusion of the area of the optic soundtrack -the gray track on left side of the illustration). These two characteristics are central to the format.

It was adopted by Hollywood starting with Greystoke in 1984, under the format name Super Techniscope. It also received much early publicity for making the cockpit shots in Top Gun possible, since it was otherwise impossible to fit 35 mm cameras with large anamorphic lenses into the small free space in the cockpit. Later, as other camera rental houses and labs started to embrace the format, Super 35 became popular in the mid-1990s, and is now considered a ubiquitous production process, with usage on well over a thousand feature films. It is often the standard production format for television shows, music videos, and commercials. Since none of these require a release print, it is unnecessary to reserve space for an optical soundtrack.

When composing for 1.85:1, it was known as Super 1.85, since it was larger than standard 1.85.

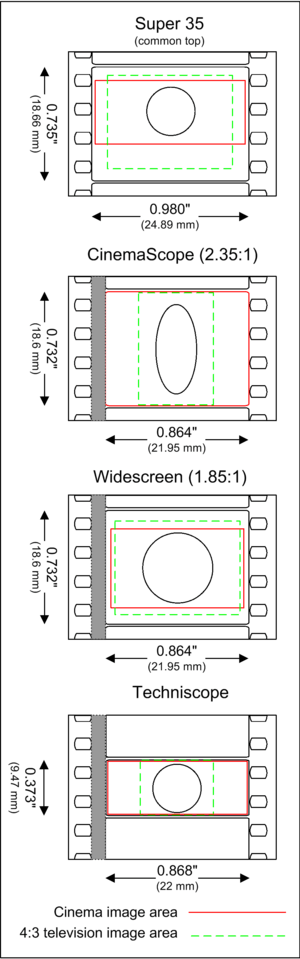

When composing for 2.39:1, it was often typical to employ either a "common center", which keeps the 2.39 extraction area at the center of the film that results in extra headroom if opened up to 4:3 or 16:9, or a "common top", which shifts the 2.39 extraction area upwards on the film so that it shared a common top line with a centered 1.85:1 frame. This allowed frame compositions with actors to remain relatively unaffected when producing a 4:3 or 16:9 full screen version with similar headrooms. The downside with common top extraction is that lens flares may not be aligned properly as light sources that are in the center of the full frame appear slightly lower than usual in 2.39 and corner fall-offs and other distortions are not optically centered properly. Also in wide shots, there is too much footroom and not enough headroom and extreme close ups of actors faces as well as their foreheads are still cut off but more picture is gained below the frame. As 16:9 televisions increased in popularity, it became more practical for productions to use the "common center" extraction, which frames across the center of the film, although a "common third" extraction is used if directors want similar headrooms between 2.39 & 16:9 versions.

The Super 35 format has also gained attraction for use in films with extensive visual effects as the unused frame areas outside 1.85/2.39 can be used by VFX artists to film different visual effects elements with spherical lenses and more freedom to move within the frame.

Details

Super 35 is a production format. Theatres do not receive or project Super 35 prints. Rather, films are shot in a Super 35 format but are then — either through optical blowdown/matting or digital intermediate — converted into one of the standard formats to make release prints. Because of this, often productions also use Super 35's width in conjunction with a 3-perf negative pulldown to save costs on "wasted" frame area shot and accommodate camera magazines that could shoot 33% longer in time with the same length of film.

If using 4-perf, the Super 35 camera aperture is 24.89 mm × 18.66 mm (0.980 in × 0.735 in), compared to the standard Academy 35 mm film size of 21.95 mm × 16.00 mm (0.864 in × 0.630 in) and thus provides 32% more image area than the standard 35-mm format. 4-perf Super 35 is simply the original frame size that was used in 35 mm silent films. That is, it is a return to the way the film stock was used before the frame size was cropped to allow room for a soundtrack.

Super 35 competes with the use of the standard 35 mm format used with an anamorphic lens. In this comparison, advocates of Super 35 claim an advantage in production costs and flexibility; when used to make 1.85:1 or 2.39:1 theatrical prints, detractors complain of a loss in quality, due to less negative area used and more lab intermediate steps (if done optically).

Aspect ratio

Super 35 uses standard "spherical" camera lenses, which are faster, smaller, and cheaper to rent — a factor in low-budget production — and provide a wider range of lens choices to the cinematographer. The chief advantage of Super 35 for productions is its adaptability to different release formats. Super 35 negatives can be used to produce high-quality releases in any aspect ratio, as the final frame is extracted and converted from the larger full frame negative. This also means that a full-frame video release can actually use more of the frame than the theatrical release (Open matte), provided that the extra frame space is "protected for" during filming. Generally the aspect ratio(s) and extraction method (either from a common center or common topline) must be chosen by the director of photography ahead of time, so the correct ground glass can be created to let the camera operator see where the extracted frame is.

Super 35 ratios have included:

- 1.33:1 (4:3 full screen video)

- 1.78:1 (16:9, widescreen video)

- 1.85:1 ("flat" print) (Super 1.85)

- 2.00:1 (Univisium)

- 2.20:1 (70mm print)

- 2.39:1 (anamorphic print)

1.66:1 and 1.75:1 have been indicated in some Super 35 frame leader charts, although generally they have not been used for Super 35 productions due to both relative lack of usage since the rise of Super 35 and their greater use of negative frame space by virtue of their increased vertical dimension.

Theoretically, 2.39:1 release prints made from Super 35 should have slightly lower technical quality than films produced directly in the anamorphic format. Because part of the Super 35 image is thrown away when printing to this format, films originated with anamorphic lenses use a larger negative area. Super 35 has continually been popular with television shows, due to the lack of a need for a final release print; with the advent of widescreen television sets, 3-perf Super 35 – with a native 1.78:1 (16:9) ratio – was widely used for widescreen television shows until the advent of digital shooting. 3-perf Super 35 was also used for some time for 2.39:1 feature films, and the digital intermediate process made it more attractive because it allowed the optical processing formerly required to be skipped entirely.

Examples

Franchises that used the Super 35 format include The Matrix, The Fast and the Furious, Harry Potter, Bourne, the first three Pirates of the Caribbean movies, National Treasure, the first two The Chronicles of Narnia movies, the first three live-action Alvin and the Chipmunks movies (Super 1.85), and The Twilight Saga.

See also

- List of film formats

- Full frame

- Maxivision

- Negative pulldown

References

- "About Us: Superscope Technologies Co." - Superscope website, Archived at the Wayback Machine

- "Joe Dunton". IMDb. Retrieved 2016-10-07.

- Heuring, David (June 22, 2012). "Cinematographer Darius Khondji on Woody Allen's To Rome with Love". StudioDaily. Archived from the original on January 27, 2020. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- "Aguirresarobe Reteams with Allen for Blue Jasmine". InCamera Magazine. Kodak. May 14, 2013. Archived from the original on October 10, 2015. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- Marcks, Iain (February 2016). "Hail, Caesar". American Cinematographer. American Society of Cinematographers. Retrieved July 17, 2020.

- Oppenheimer, Jean (April 2010). "Production Slate: Police Under Pressure". American Cinematographer. American Society of Cinematographers. Retrieved July 17, 2020.

- "I Am Number Four Edit Bay Visit". ComingSoon.net. December 8, 2010. Retrieved June 19, 2020.

- Johnson, Shelly (February 2010). "Bad Moon Rising". American Cinematographer. American Society of Cinematographers. Retrieved July 17, 2020.