Howards End (film)

Howards End is a 1992 romantic drama film based upon the 1910 novel of the same name by E. M. Forster, a story of class relations in turn-of-the-20th-century Britain. The film — produced by Merchant Ivory Productions as their third adaptation of a Forster novel (following A Room with a View in 1985 and Maurice in 1987) — was the first film to be released by Sony Pictures Classics. The screenplay was written by Ruth Prawer Jhabvala, directed by James Ivory, and produced by Ismail Merchant.

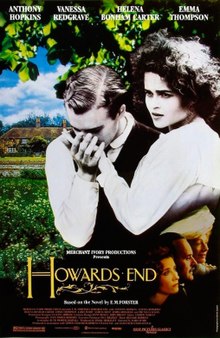

| Howards End | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | James Ivory |

| Produced by | Ismail Merchant |

| Screenplay by | Ruth Prawer Jhabvala |

| Based on | Howards End by E. M. Forster |

| Starring | |

| Music by | Richard Robbins Percy Grainger (opening and end title) |

| Cinematography | Tony Pierce-Roberts |

| Edited by | Andrew Marcus |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Sony Pictures Classics |

Release date |

|

Running time | 142 minutes[1][2] |

| Country |

|

| Language | English |

| Budget | $8 million |

| Box office | $26.3 million |

Howards End was entered as an official selection for the Cannes International Film Festival and won the 45th Anniversary Award. In 1993, the film received nine Academy Award nominations, including Best Picture. The film won three awards, including for Best Art Direction (Art Direction: Luciana Arrighi; Set Decoration: Ian Whittaker). Ruth Prawer Jhabvala earned her second Academy Award for Best Screenplay Based on Material Previously Produced or Published, while Emma Thompson won the 1992 Academy Award for Best Actress.

Plot

In Edwardian Britain, Helen Schlegel becomes engaged to Paul Wilcox during a moment of passion, while she is staying at the country home of the Wilcox family, Howards End. The Schlegels are an intellectual family of Anglo-German bourgeoisie, while the Wilcoxes are conservative and wealthy, led by hard-headed businessman Henry. Helen and Paul quickly decide against the engagement, but Helen has already sent a telegram informing her sister Margaret, which causes an uproar when the sisters' Aunt Juley arrives and causes a scene.

Months later, when the Wilcox family takes a flat across the street from the Schlegels in London, Margaret resumes her acquaintance with Ruth Wilcox, whom she had briefly met before. Ruth is descended from English yeoman stock, and it is through her family that the Wilcoxes have come to own Howards End, a house she loves dearly.

Over the course of the next few months, the two women become very good friends, even as Mrs. Wilcox's health declines. Hearing that the lease on the Schlegels' house is due to expire, Ruth on her death bed bequeaths Howards End to Margaret. This causes great consternation to the Wilcoxes, who refuse to believe that Ruth was in her "right mind" or could possibly have intended her home to go to a relative stranger. The Wilcoxes burn the piece of paper on which Ruth's bequest is written, deciding to ignore it completely.

Henry Wilcox, Ruth's widower, begins to develop an attraction to Margaret, and agrees to assist her in finding a new home. Eventually he proposes marriage, which Margaret accepts.

Some time before this, the Schlegels had befriended a self improving young clerk, Leonard Bast, who lives with a woman of dubious origins named Jacky. Both sisters find Leonard remarkable, appreciating his intellectual curiosity and desire to improve his lot in life. The sisters pass along advice from Henry to the effect that Leonard must leave his post, because the insurance company he works for is supposedly heading for bankruptcy. Leonard takes the advice and quits, but has to settle for a job paying much less, which he eventually loses altogether due to downsizing of its business. Helen is later enraged to learn that Henry's advice was wrong; Leonard's first employer had been perfectly sound but won't reemploy him.

Months later, Henry and Margaret host the wedding of his daughter Evie at his Shropshire estate. Margaret is shocked when Helen arrives with the Basts, whom she has found living in poverty. Considering that Henry is responsible for their plight, Helen demands that he help them. However, Jacky becomes drunk at the reception, and when she sees Henry she recognizes and exposes him as a former lover from years ago. Henry is embarrassed and ashamed to have been revealed as an adulterer in front of Margaret, but she forgives him and agrees to send the Basts away. After the wedding, Helen, upset with Margaret's decision to marry a man she loathes prepares to leave for Germany, but not before giving in to her attraction for Leonard having sex with him while out boating.

Fearing that the Basts will be penniless, Helen sends instruction from Germany to her donnish brother Tibby to make over £5000 of her own money to Leonard. Leonard returns the cheque uncashed, refusing to accept the money through pride.

Margaret and Henry marry, with the pair arranging to use Howards End as storage for Margaret and her siblings' belongings. After months of only hearing from Helen through postcards, Margaret grows concerned. When Aunt Juley falls ill, Helen returns to England to visit her, but when she receives word that her aunt has recovered, avoids seeing Margaret or any of her family.

Fearing that Helen is mentally unstable, Margaret lures her to Howards End to collect her belongings, only to turn up herself with Henry and a doctor. However, on first glance she realizes that Helen is heavily pregnant. Helen insists on returning to Germany to raise her baby alone but asks that she be allowed to stay the night at Howards End before she leaves. When Margaret requests this from Henry, he stubbornly refuses and the couple bicker.

The next day, Leonard, still living unhappily in poverty with Jacky, leaves London and travels to Howards End to see the Schlegels. When he arrives he finds the pair, as well as Henry's brutish eldest son Charles. Charles quickly realizes that Leonard is the baby's father and begins assaulting him for "dishonoring" Helen.

In his rage, Charles beats Leonard with the flat of a sword, and Leonard grabs onto a bookcase for support. The bookcase collapses on him, which causes Leonard to have a heart attack and die.

Margaret tells Henry that she is leaving him to help Helen raise Helen's baby, and Henry breaks down, telling her the police inquest will charge Charles with manslaughter.

A year later, Paul, Evie, and Charles's wife Dolly gather at Howards End. Henry and Margaret are still together, and living with Helen and her young son. Henry tells the others that, upon his death, Margaret will receive Howards End—but no money, at her own request. Dolly points out the irony of Margaret's inheriting the house, revealing Mrs. Wilcox's dying wish to Margaret for the first time. Henry admits to what happened, and Margaret appears to forgive him.

Cast

- Emma Thompson ... Margaret Schlegel

- Helena Bonham Carter ... Helen Schlegel

- Vanessa Redgrave ... Ruth Wilcox

- Joseph Bennett ... Paul Wilcox

- Prunella Scales ... Aunt Juley

- Adrian Ross Magenty ... Tibby Schlegel

- Jo Kendall ... Annie

- Anthony Hopkins ... Henry Wilcox

- James Wilby ... Charles Wilcox

- Jemma Redgrave ... Evie Wilcox

- Ian Latimer ... Stationmaster

- Samuel West ... Leonard Bast

- Simon Callow ... Music and Meaning Lecturer (cameo)

- Mary Nash ... Pianist

- Siegbert Prawer ... Man Asking a Question

- Susie Lindeman ... Dolly Wilcox

- Nicola Duffett ... Jacky Bast

- Atalanta White... Maid at Howards End

- Gerald Paris ... Porphyrion Supervisor

- Mark Payton ... Percy Cahill

- David Delaney ... Simpson's Carver

- Mary McWilliams ... Wilcox Baby

- Barbara Hicks ... Miss Avery

- Rodney Rymell ... Chauffeur

- Luke Parry ... Tom, the Farmer's Boy

- Antony Gilding ... Bank Supervisor

- Peter Cellier ... Colonel Fussell

- Crispin Bonham Carter ... Albert Fussell

- Patricia Lawrence, Margery Mason ... Wedding Guests

- Jim Bowden ... Martlett

- Alan James ... Porphyrion Chief Clerk

- Jocelyn Cobb ... Telegraph Operator

- Peter Darling ... Doctor

- Terence Sach ... Deliveryman

- Brian Lipson ... Police Inspector

- Barr Heckstall-Smith ... Helen's Child

- Mark Tandy, Andrew St. Clair, Anne Lambton, Emma Godfrey, Duncan Brown, Iain Kelly ... Luncheon Guests

- Allie Byrne, Sally Geoghegan, Paula Stockbridge, Bridget Duvall, Lucy Freeman, Harriet Stewart, Tina Leslie ... Blue-stockings

Production

Financing

Merchant-Ivory encountered difficulty securing funding for Howards End, the budget of which stood at $8 million. This was considerably larger than that of Maurice and A Room with a View, which led to trouble in raising capital in the UK and the United States. Orion Pictures, the film's distributor, was on the verge of bankruptcy and only contributed a small amount to the overall budget.[4] A solution presented itself when Merchant Ivory sought funding through an intermediary in Japan, where the previous Forster adaptations, particularly Maurice, had been very successful. Eventually Japanese companies including the Sumitomo Corporation, Japan Satellite Broadcasting, and the Imagica Corporation provided the bulk of the film's financing. The distribution problem would be solved when the heads of Orion Classics departed the company for Sony Pictures, creating the entirely new division of Sony Pictures Classics. Howards End was the first title distributed by this new division.[5]

Casting

Anthony Hopkins accepted the part of Henry Wilcox after reading the script, passed to him by a young woman who was helping edit Slaves of New York and The Silence of the Lambs simultaneously in the same building. Phoebe Nicholls, Joely Richardson, Miranda Richardson, and Tilda Swinton were all considered for the part of Margaret Schlegel before Emma Thompson accepted the role. James Ivory was unaware of Emma Thompson before she was recommended to him by Simon Callow, who made a small cameo as the music lecturer in the concert scene.[6]Jemma Redgrave (Evie Wilcox), who played the daughter of Vanessa Redgrave's character (Ruth Wilcox), is her niece off-screen. Samuel West, who played Leonard Bast, is the son of Prunella Scales, who played Aunt Juley.

According to James Ivory, although Vanessa Redgrave was his preferred choice for the role of Ruth Wilcox, her participation was uncertain until the last moment, because she was committed to other projects and it took some time to negotiate an acceptable salary.[6][7] When she did agree to play the role of Mrs. Wilcox, she mistakenly believed she would be playing Margaret; only when she showed up on set to begin filming her scenes did the person in Hair and Makeup explain that she would be playing the elder Mrs. Wilcox.[6]

Music

- "Bridal Lullaby" by Percy Grainger

Courtesy of Bardie Edition - "Mock Morris" by Percy Grainger

Courtesy of Schott & Co., Ltd. - 5th Symphony by Ludwig van Beethoven (uncredited)

The score was composed by Richard Robbins, with elements of the score based on Percy Grainger's works "Bridal Lullaby" and "Mock Morris". The piano pieces were performed by the English concert pianist Martin Jones.

Filming locations

Filming locations in London included a house in Victoria Square, which stood in for the Schlegel home, Fortnum & Mason in Piccadilly, Simpson's-in-the-Strand restaurant, and St. Pancras Station.[8] Areas around the Admiralty Arch and in front of the Royal Exchange in the City of London were dressed to film traffic scenes of 1910 London. The scene where Margaret and Helen stroll with Henry in the evening was filmed on Chiswick Mall in Chiswick, London. The bank where Leonard encounters Helen is the lobby of the Baltic Exchange, 30 St. Mary Axe, London. Soon after filming the building was bombed and destroyed by the IRA. The Rosewood London on High Holborn, which was then the Pearl Assurance Building, represented the Porphyrion Fire Insurance Company.[8]

The quadrangle of the Founder's Building at Royal Holloway, University of London stood in for the hospital where Margaret visits Mrs. Wilcox. The "Howards End" house in the countryside is Peppard Cottage in Rotherfield Peppard, Oxfordshire. At the time it was owned by an antique silver dealer with whom production designer Luciana Arrighi was acquainted. The bluebell wood where Leonard strolls in his dream, as well as Dolly and Charles' house, were filmed nearby.[9] Henry's country house, Honiton, was actually Brampton Bryan Hall in Herefordshire, near the Welsh border.[10] Bewdley railway station on the historic Severn Valley Railway featured as Hilton station.[11]

Release

Critical reception

The film received massive critical acclaim. On 5 June 2005, Roger Ebert included it on his list of "Great Movies".[12] Leonard Maltin awarded the film a rare 4 out of 4 star rating, and called the film "Extraordinarily good on every level."[13]

Review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes reports that 94% of 65 reviews are positive for the film, and the average rating is 8.3/10. The site's critical consensus reads, "A superbly-mounted adaptation of E.M. Forster's tale of British class tension, with exceptional performances all round, Howards End ranks among the best of Merchant-Ivory's work."[14] On Metacritic, the film holds a score of 89 out of 100, based on 10 reviews, indicating "universal acclaim".[15]

According to the website Box Office Mojo, the total gross of the film stands at $26.3 million.[16]

In 2016, the film was selected for screening as part of the Cannes Classics section at the 2016 Cannes Film Festival,[17] and was released theatrically after restoration on 26 August 2016.[18]

Howards End was placed on more top ten lists than any other film in 1992, edging out The Player and Unforgiven. It was placed on 82 of the 106 film critics polled.[19]

Home media

The Criterion Collection released Blu-ray and DVD versions of the film on 3 November 2009, which have since gone out of print. The release was unfortunately subject to a bronzing issue which would discolor the disc bronze and render it unplayable, due to a pressing issue at the factory, though not every disc was subject to bronzing. Cohen Film Collection released their own special edition Blu-ray on 6 December 2016.

Awards and nominations

65th Academy Awards (1992)

- Won: Best Actress - Emma Thompson

- Won: Best Screenplay Based on Material Previously Produced or Published - Ruth Prawer Jhabvala

- Won: Best Art Direction - Art Direction: Luciana Arrighi; Set Decoration: Ian Whittaker

- Nominated: Best Picture - Ismail Merchant

- Nominated: Best Director - James Ivory

- Nominated: Best Supporting Actress - Vanessa Redgrave

- Nominated: Best Cinematography - Tony Pierce-Roberts

- Nominated: Best Costume Design - Jenny Beavan and John Bright

- Nominated: Best Original Score - Richard Robbins

46th British Academy Film (BAFTA) Awards (1992)

- Won: Best Film - Ismail Merchant

- Won: Best Actress in a Leading Role - Emma Thompson

- Nominated: Best Direction - James Ivory

- Nominated: Best Adapted Screenplay - Ruth Prawer Jhabvala

- Nominated: Best Actress in a Supporting Role - Helena Bonham Carter

- Nominated: Best Actor in a Supporting Role - Samuel West

- Nominated: Best Cinematography - Tony Pierce-Roberts

- Nominated: Best Production Design - Luciana Arrighi

- Nominated: Best Costume Design - Jenny Beavan and John Bright

- Nominated: Best Editing - Andrew Marcus

- Nominated: Best Makeup and Hair - Christine Beveridge

50th Golden Globe Awards (1992)

- Won: Best Actress in a Motion Picture - Drama - Emma Thompson

- Nominated: Best Director - James Ivory

- Nominated: Best Motion Picture – Drama - Ismail Merchant

- Nominated: Best Screenplay - Ruth Prawer Jhabvala

1992 Directors Guild of America Awards

- Nominated: Outstanding Directorial Achievement in Motion Pictures - James Ivory

1992 Writers Guild of America Awards

- Nominated: Best Screenplay Based on Material Previously Produced or Published - Ruth Prawer Jhabvala

1992 New York Film Critics Circle Awards

- Won: Best Actress - Emma Thompson

- Nominated: Best Film - Ismail Merchant

- Nominated: Best Director - James Ivory

1992 Los Angeles Film Critics Association Awards

- Won: Best Actress - Emma Thompson

1992 National Society of Film Critics Awards

- Won: Best Actress - Emma Thompson

- Nominated: Best Supporting Actress - Vanessa Redgrave

1992 National Board of Review Awards

- Won: Best Film - Ismail Merchant

- Won: Best Director - James Ivory

- Won: Best Actress - Emma Thompson

- Won: 45th Anniversary Prize - James Ivory[20]

- Nominated: Palme d'Or

References

- "HOWARDS END". British Board of Film Classification. Retrieved 26 December 2017.

- "HOWARDS END - Festival de Cannes". Festival de Cannes. 2016. Retrieved 26 December 2017.

- "British Council Film: Howards End". British Council. 28 April 2016.

UK, Japan, US coproduction

- Building Howards End (dvd). Criterion Collection. 2005.

- "Sony Pictures Classics - About Us". SonyClassics.com.

- Film Society of Lincoln Center (28 July 2016). 'Howards End' Q&A James Ivory. YouTube.com. Retrieved 6 August 2018.

- Howards End Commentary by Ismail Merchant & James Ivory (dvd). Criterion Collection. 2005.

- John Pym (1995). Merchant Ivory's English Landscape. p. 93.

- "Howard's End". The Castles and Manor Houses of Cinema's Greatest Period Films. Architectural Digest. January 2013. Retrieved 2 January 2013.

- Country Life. "Interview, Edward Harley". Retrieved 11 May 2010.

- "Howards End film locations". Movie-locations.com. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- Ebert, Roger (5 June 2005). "Howards End (1992)". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 1 May 2019.

- Martin, Leonard (2015). Leonard Maltin's Movie Guide. Signet Books. p. 653. ISBN 978-0-451-46849-9.

- "Howards End". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- "Howards End". Metacritic. Retrieved 19 August 2016.

- "Howards End". Box Office Mojo.

- "Cannes Classics 2016". Cannes Film Festival. 20 April 2016. Archived from the original on 10 February 2017. Retrieved 21 April 2016.

- McNary, Dave (17 June 2016). "Restored 'Howards End' to Be Released in Theaters". Variety.com. Retrieved 28 October 2017.

- https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1993-01-24-ca-2356-story.html

- "Festival de Cannes: Howards End". festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 14 August 2009.

External links

- Howards End on IMDb

- Howards End at Rotten Tomatoes

- Howards End: All Is Grace an essay by Kenneth Turan at the Criterion Collection