Stone cross

Stone crosses (German: Steinkreuze) in Central Europe are usually bulky Christian monuments, some 80–120 cm (31–47 in) high and 40–60 cm (16–24 in) wide, that were almost always hewn from a single block of stone, usually granite, sandstone, limestone or basalt. They are amongst the oldest open-air monuments. A larger variant of the stone cross, with elements of a wayside shrine is called a shaft cross (Schaftkreuz).

Distribution

These small monuments are found along old routes and crossroads, by trees and forest edges, on hilltops or on old municipal and territorial boundaries. They are especially common in the Upper Palatinate region of Bavaria and in Central Germany, whereas basalt crosses occur almost exclusively in the Eifel region.

Unfortunately, many of these stone witnesses to a bygone era have disappeared due to carelessness, ignorance or deliberate destruction. As Rainer H. Schmeissner writes in his 1977 monograph, Stone Crosses in the Upper Palatinate, there are still about 300 such monuments in the Upper Palatinate alone. Four hundred examples of them were still around the turn of the century, which is almost twice as many as in Lower and Upper Bavaria combined. In 1977-1980, the National Museum of Prehistory at Dresden issued inventories for Saxony that included a list of 436 stone crosses and cross slabs.

Condition

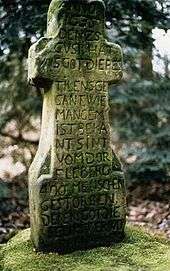

A large number of these coarsely hewn crosses have already been heavily weathered. On many, a picture has been carved; only rarely do they carry an inscription.

Apart from damage caused by weathering, willful or negligent acts, some damage to stone crosses also arose from popular belief. An old stone spell says that by cutting off a piece of a stone cross and throwing it into running water, sorcery and misfortune will be averted.[1] In addition, it was sometimes believed that magical power was attached to the so-called "flour" obtained by scraping stone crosses.[2]

Purpose

The actual reason for setting up stone crosses is only known in a few cases. In others there is no clue as to their significance. The only thing that is certain is that the majority were erected between the 13th century and the time around 1530.

In spite of various opinions and intensive archival research, a touch of mystery and enigma still surrounds these rough, massive crosses. In some cases, legends and folklore are bound up in the history of stone crosses. Occasionally it is reported that moving an atonement cross (conciliation cross) would have led to subsequent accidents.

Atonement crosses

From 1300, it appears to have been common practice, following a serious crime, for a stone atonement cross to be erected by the perpetrator at the scene of the crime or other location specified by the victim's family. If anyone was killed in the course of a dispute or otherwise without intention, the culprit had to reach an atonement agreement with the family of the victim. An atonement contract would then be concluded between the two parties under private law. Most atonement crosses are associated with manslaughter or murder. At the very least, these have to bear an inscription describing the actual event, otherwise they cannot clearly be associated with any certainty with an atonement contract. Often, these stone crosses had pictures of weapons carved on them, which are taken to be the murder weapons. In the Upper Palatinate and Saxony, atonement contracts have survived that expressly agreed the erection of an atonement cross by the perpetrator of the crime.

The historical and religious background is that, in Roman Catholic times, passers by were to be encouraged to say prayers of intercession for those who had died without the opportunity for last rites. Hence, in Protestant areas, the erection of such crosses abruptly ceased about 1530. Equally important, however, was the introduction of the blood court jurisdiction, the so-called Carolina, by Charles V in 1532. This saw private law atonement contracts being replaced by state jurisdiction. Again, this can be well seen in the sudden absence of atonement contracts in the records of the Early Modern Period.

Both factors together - the introduction of the Reformation into certain areas and the introduction of the carolina - had the effect that no more atonement crosses were put up from that point onwards. More recent stone crosses in Roman Catholic areas may well have continued the medieval custom of intercessory prayers for the dead (Fürbittgedanken). In Protestant areas, however, only simple memorial stones were erected (after a murder, accident, plague, etc.), but these were much rarer.

The reason for the erection of a cross in front of Berlin's St. Mary's Church is known for certain. In 1325, the provost of Bernau was killed in Berlin. In addition to suffering a ten-year imperial ban, Berlin had to build an atonement cross, which is still to be found by the entrance to the church.

Memorial crosses

It is certainly incorrect to describe the majority of stone crosses as atonement crosses. They could also be placed by relatives following a fatal accident or - as is recorded in writing in Zittau in 1392 - in gratitude for the charitable foundation of a Kuttenberg citizen for repairing a mountainous border road to the town of Gabel.

In the vernacular, stone crosses have numerous regional names that go back to tragic historical events. Along the Bohemian Forest they are called "Hussite crosses" and in northern Upper Palatinate they are "Swedish crosses", recalling the Thirty Years' War. Several legends suggest that Swedes lie buried beneath these monuments. In the West, they are also called "French crosses". The majority of these crosses, however, were erected long before these events, so it is likely that these names arise from later reinterpretation, or that the original reason was supplanted by the need to commemorate massacres or battles in the vicinity of these crosses, or even that they mark the site of buried victims. Some of the crosses could also be early "plague crosses".

It is likely that the crosses, which are always found on their own and deep in the countryside, are on sites that were deemed suitable places for mass graves, depending on regional custom and the acceptance of ancient stone crosses as sufficiently holy sites, or as a place for "heathens" that could not be buried in consecrated ground in a graveyard.

Wayside and weather crosses

It is also probable that some crosses served as boundary markers, direction signs (wayside crosses), boundary stones of tax exempt or otherwise privileged territory (Freisteine) or weather crosses.

Court and oath crosses

Several old crosses could also be connected with ancient forms of jurisdiction, such as "oath crosses" (Schwurkreuze) at which contracts were sealed.

Gallery

Hail cross near Linnich in the Zülpicher Börde

Hail cross near Linnich in the Zülpicher Börde Ansverus cross in Einhaus

Ansverus cross in Einhaus

Stone cross (also called a Hussite cross) in East Saxon Leppersdorf

Stone cross (also called a Hussite cross) in East Saxon Leppersdorf Stone cross in Hessian Wippershain

Stone cross in Hessian Wippershain Hersfeld double cross in the town of Bad Hersfeld

Hersfeld double cross in the town of Bad Hersfeld Conciliation cross in Ziegenhain

Conciliation cross in Ziegenhain Conciliation cross in Rydułtowy

Conciliation cross in Rydułtowy

See also

- Stone crosses in Cornwall

- Wayside shrine

- Explanation of the categories in the small and wayside monument data bank(pdf; 2.7 MB) www.lernende-gemeinde.at, as at: 20 February 2012

References

- -Heinz Hartmann: Zeugen mittelalterlichen Brauchtums in: Schwaben & Franken, heimatgeschichtliche Beilage der Heilbronner Stimme 42. Jg., No. 4, Juni 1996

- J. Rünemann: Rillen und Näpfchen auf sakralen Denkmalen. In: Mitteilungsblatt der internationalen Gesellschaft für Geschichte der Pharmazie No. 29, 1977

Literature

- Kurt Müller-Veltin: Mittelrheinische Steinkreuze aus Basaltlava. 2nd, reworked and expanded edn., Cologne: Rheinischer Verein für Denkmalpflege und Landschaftsschutz, 2001 ISBN 3-88094-570-5

- Störzner, Bernhard Friedrich: Was die Heimat erzählt, Verlag Arwed Strauch, Leipzig, 1904 (digitalisation by SLUB Dresden)

- Kuhfahl, Gustav: Die alten Steinkreuze in Sachsen. Dresden, 1928 and 1936 (Digitized)

- Köber, Heinz: Die alten Steinkreuze und Sühnesteine Thüringens. Erfurt, 1960

- Ost, Gerhard: Alte Steinkreuze in den Kreisen Jena, Stadtroda und Eisenberg. Jena, 1962

- Deubler, Heinz, Künstler, Richard und Ost, Gerhard: Steinerne Flurdenkmale in Ostthüringen (Bezirk Gera). Gera o. J., (1977)

- Müller/Quietzsch: Steinkreuze und Kreuzsteine in Sachsen I Inv. Bez. Dresden. Berlin, 1977

- Wendt, Hans-J.: Steinkreuze und Kreuzsteine in Sachsen II Inv. Bez. Karl-Marx-Stadt. Berlin, 1979

- Quietzsch, Harald: Steinkreuze und Kreuzsteine in Sachsen III Inv. Bez. Leipzig. Berlin, 1980

- Neuber, Dietrich und Wetzel, Günter: Steinkreuze und Kreuzsteine. Inventar Bezirk Cottbus. Cottbus, 1980.. = Geschichte und Gegenwart des Bezirkes Cottbus (Niederlausitzer Studien), Sonderheft

- Schmeissner, Rainer H.: Steinkreuze in der Oberpfalz. Regensburg 1977

- Torke, Horst: Alte Steinkreuze zwischen Dresden, Pirna und Sächsischer Schweiz. Pirna, 1983

- Störzner, Frank: Steinkreuze in Thüringen. Katalog Bezirk Erfurt. Weimar, 1984. = Weimarer Monographien zur Ur- und Frühgeschichte 10

- Bedal, Karl: Rätselhaftes, versunken, vergessen, unsichtbar. Doch genau vermessen. Hof, 1986

- Müller/Baumann: Kreuzsteine und Steinkreuze in Niedersachsen, Bremen und Hamburg. Hamelin, 1988

- Störzner, Frank: Steinkreuze in Thüringen. Katalog Bezirke Gera–Suhl. Weimar 1988. = Weimarer Monographien zur Ur- und Frühgeschichte 21

- Torke, Horst: Steinerne Zeugen der Geschichte im Landkreis Sächsische Schweiz. Pirna, 1998 ISBN 3-932460-09-X

- … und erschlugen sich um ein Stücklein Brot. Sühnekreuze in den Landkreisen Schwäbisch Hall und Hohenlohe. eine Fotodokumentation von Eva Maria Kraiss; Marion Reuter; Bernhard Losch. Künzelsau, 2000. ISBN 3-934350-31-3

- Walter Saal: Steinkreuze und Kreuzsteine im Bezirk Halle. Landesmuseum f. Vorgeschichte, Halle 1989; ISBN 3-910010-01-6.

- Heinrich Riebeling: Steinkreuze und Kreuzsteine in Hessen Werner Noltemeyer Verlag, Dossenheim/Heidelberg, 1977; ISBN 3-88172-005-7

- Ada Paul: Steinkreuze und Kreuzsteine in Österreich, Horn, 1975

- Ada Paul: Steinkreuze und Kreuzsteine in Österreich (Nachtrag), Regensburg, 1988

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Stone crosses. |

- "Sühnekreuze und Mordsteine". suehnekreuz.de. Retrieved 2011-09-05. – Informationen zu Steinkreuzen und deren Standorten in Deutschland

- Horst Torke (1983). "Vom äußeren Bild der Steinkreuze: Steinkreuz und Kreuzstein". Alte Steinkreuze zwischen Dresden, Pirna und Sächsischer Schweiz. suehnekreuz.de. Retrieved 2011-09-05.

- "Wegekreuze in der Eifel". wegekreuze.de. Retrieved 2011-09-05.

- Steffen Raßloff: Zum Sühnekreuz für einen Mord bei Erfurt 1323. In: Thüringer Allgemeine vom 1. September 2012.

.jpg)