Fylfot

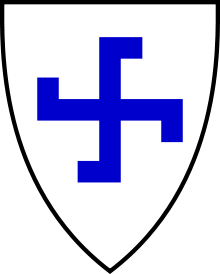

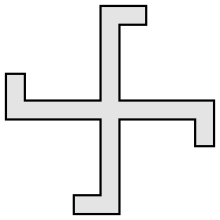

Fylfot or fylfot cross /ˈfɪlfɒt/ (FILL-fot), is an English symbol equivalent to the sauwastika, or left-facing swastika. It is a cross with perpendicular extensions, usually at 90° or close angles, radiating in the same direction. Its right-facing variant is referred to as a gammadion. According to some modern texts on heraldry, the fylfot is upright and typically with truncated limbs, as shown in the figure at right.

Etymology

The most commonly cited etymology for this is that it comes from the notion common among nineteenth-century antiquarians, but based on only a single 1500 manuscript, that it was used to fill empty space at the foot of stained-glass windows in medieval churches.[1] This etymology is often cited in modern dictionaries (such as the Collins English Dictionary and Merriam-Webster OnLine[2]).

Thomas Wilson (1896), suggested other etymologies, now considered untenable:

- "In Great Britain the common name given to the Swastika from Anglo-Saxon times ... was Fylfot, said to have been derived from the Anglo-Saxon fower fot, meaning four-footed, or many-footed."[3]

- "The word [Fylfot] is Scandinavian and is compounded of Old Norse fiǫl-, equivalent to the Anglo-Saxon fela, German viel, "many", and fótr, "foot", the many-footed figure."[4] The Germanic root fele is cognate with English full, which has the sense of "many". Both fele and full are in turn related to the Greek poly-, all of which stem from the proto-Indo-European root *ple-. A fylfot is thus a "poly-foot", to wit, a "many-footed" sigil.

History

The Fylfot, together with its sister figure the gammadion, has been found in a great variety of contexts over the centuries. It has occurred in both secular and sacred contexts in the British Isles, elsewhere in Europe, in Asia Minor[5] and in Africa.[6]

While these two terms might be broadly interchangeable in some places, we can detect a certain degree of affinity between term and terrain. Thus we might usefully associate the Gammadion more with Byzantium, Rome and Graeco-Roman culture on the one hand, and the Fylfot more with Celtic and Anglo-Saxon culture on the other. Although the Gammadion is very similar to the Fylfot in appearance, it is thought to have originated from the conjunction of four capital 'Gammas', Gamma being the third letter of the Greek alphabet.

Both of these swastika-like crosses may have been indigenous to the British Isles before the Roman invasion. Certainly they were in evidence a thousand years earlier but these may have been largely imports.[7] They were certainly substantially in evidence during the Romano-British period with widespread examples of the duplicated Greek fret motif appearing on mosaics.[8] After the withdrawal of the Romans in the early 5th century there followed the Anglo-Saxon and Jutish migrations.

We know that the Fylfot was very popular amongst these incoming tribes from Northern Europe as we find it on artefacts such as brooches, sword hilts and funerary urns.[9] Although the findings at Sutton Hoo are most instructive about the style of lordly Anglo-Saxon burials, the Fylfot or Gammadion on the silver dish unearthed there clearly had an Eastern provenance.[10]

The Fylfot was widely adopted in the early Christian centuries. It is found extensively in the Roman catacombs. A most unusual example of its usage is to be found in the porch of the parish church of Great Canfield, Essex, England.[11] As the parish guide rightly states, the Fylfot or Gammadion can be traced back to the Roman catacombs where it appears in both Christian and pagan contexts.[12] More recently it has been found on grave-slabs in Scotland and Ireland.[13] A particularly interesting example was found in Barhobble, Wigtownshire in Scotland.[14]

Gospel books also contain examples of this form of the Christian cross.[15] The most notable examples are probably the Book of Kells and the Lindisfarne Gospels. Mention must also be made of an intriguing example of this decoration that occurs on the Ardagh Chalice.[16]

From the early 14th Century on, the Fylfot was often used to adorn Eucharistic robes. During that period it appeared on the monumental brasses that preserved the memory of those priests thus attired.[17] They are mostly to be found in East Anglia and the Home Counties.[18]

Probably its most conspicuous usage has been its incorporation in stained glass windows notably in Cambridge and Edinburgh. In Cambridge it is found in the baptismal window of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, together with other allied Christian symbols, originating in the 19th century.[19] In Scotland, it is found in a window in the Scottish National War Memorial in Edinburgh. The work was undertaken by Douglas Strachan and installed during the 1920s. He was also responsible for a window in the chapel of Westminster College, Cambridge. A similar usage is to be found in the Central Congregational Church in Providence, Rhode Island, USA.

It was not a little surprising to find the Fylfot on church bells in England. They were adopted by the Heathcote family in Derbyshire as part of their iconographic tradition in the 16th and 17th centuries. This is probably an example where pagan and Christian influence both have a part to play as the Fylfot was amongst other things the symbol of Thor, the Norse god of thunder[20] and its use on bells suggests it was linked to the dispelling of thunder in popular mythology.[21]

In heraldry

In modern heraldry texts the fylfot is typically shown with truncated limbs, rather like a cross potent that's had one arm of each T cut off. It's also known as a cross cramponned, ~nnée, or ~nny, as each arm resembles a crampon or angle-iron (compare Winkelmaßkreuz in German).

Examples of fylfots in heraldry are extremely rare, and the charge is not mentioned in Oswald Barron's article on "Heraldry" in most 20th-century editions of Encyclopædia Britannica. A twentieth-century example (with four heraldic roses) can be seen in the Lotta Svärd emblem.

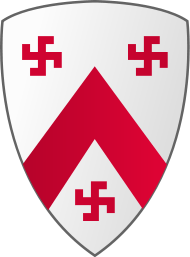

Parker's Glossary of Heraldry (see below) gives the following example:

- Argent, a chevron between three fylfots gules--Leonard CHAMBERLAYNE, Yorkshire [so drawn in MS. Harleian, 1394, pt. 129, fol. 9=fol. 349 of MS.]

(In lieu of an image from this MS., a modern rendering of this blazon is shown on the right.)

Even in the last few centuries the fylfot is conspicuous by its absence from grants of arms (understandably so since 1945; see: Swastika—Stigma).

Modern use of the term

From its use in heraldry—or from its use by antiquaries—fylfot has become an established word for this symbol, in at least British English.

However, it was only rarely used. Wilson, writing in 1896, says, "The use of Fylfot is confined to comparatively few persons in Great Britain and, possibly, Scandinavia. Outside of these countries it is scarcely known, used, or understood."

In more recent times, fylfot has gained greater currency within the areas of design history and collecting, where it is used to distinguish the swastika motif as used in designs and jewellery from that used in Nazi paraphernalia. Even though the swastika does not derive from Nazism, it has become associated with it, and fylfot functions as a more acceptable term for a "good" swastika.

Hansard for 12 June 1996[22] reports a House of Commons discussion about the badge[23] of No. 273 Fighter Squadron, Royal Air Force. In this, fylfot is used to describe the ancient symbol, and swastika used as if it refers only to the symbol used by the Nazis.

Odinic Rite (OR), a Germanic pagan organization, use both "swastika" and "fylfot" for what they claim as a "holy symbol of Odinism". The OR fylfot is depicted with curved outer limbs, more like a "sunwheel swastika" than a traditional (square) swastika or heraldic fylfot.[24]

See also

- Buddhism

- Hinduism

- Jainism

- Swastika

- Triskelion

- Western use of the Swastika in the early 20th century

Notes

- "fylfot". Oxford English Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. September 2005. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- "Fylfot". Free Merriam-Webster Dictionary. 2015. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- quoting from Greg, Robert Philips (1885). "Meaning and Origin of Fylfot and Swastika". Archaeologia. XLVIII (Part II): 298. and Goblet d'Alviella, Eugène (1891). The Migration of Symbols. p. 39. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- quoting from Waring, John Burley (1874). Ceramic Art in Remote Ages: with essays on the symbols of the circle, the cross and circle, the circle and ray ornament, the fylfot and the serpent, showing their relation to the primitive forms of solar and nature worship. London: John B. Day. p. 10.

- Wujewski, Tomasz (1991). Anatolian Sepulchral Stelae in Roman Times. Poznań: Adam Mickiewicz University Press. pp. 23–24. ISBN 9788323203056.

- Buxton, David Roden (1947). "The Christian Antiquities of Northern Ethiopia". Archaeologia. Society of Antiquaries of London. 92: 11 & 23. doi:10.1017/S0261340900009863.

- Green, Miranda Jane (1984). The Wheel as a cult symbol in the Romano-Celtic world : with special reference to Gaul and Britain. Brussels: Latomus (Revue d'Etudes Latines). pp. 295–296. ISBN 9782870311233.

- Neal, David S. (1981). Roman Mosaics in Britain. London: Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies. p. 19.

- Taylor, Stephen (2006). The Fylfot File: Studies in the origin and significance of the Fylfot-Cross and allied symbolism within the British Isles. Cambridge: Perfect Publishers. pp. 37–40. ISBN 9781905399222.

- Evans, Angela Care (1986). The Sutton Hoo Ship Burial. London: British Museum Publications. pp. 57–58. ISBN 9780714105444.

- Waller, J. G. (1883). "The Church of Great Canfield, Essex". Transactions of the Essex Archaeological Society. New Series. II (Part IV): 377–388.

- Della Portella, Ivana (2002) [2000]. Subterranean Rome (Eng. ed.). Venice: Arsenale. p. 106–107. ISBN 9788877432810.

- Henry, Françoise (1940). Irish Art in the early Christian period (to 800 A.D.). London: Methuen & Co. pp. 119–120.

- Cormack, William Fleming (1995). "Barhobble". Transactions of the Dumfriesshire and Galloway Natural History and Antiquarian Society. (passim)

- Henderson, George (1987). From Durrow to Kells : the insular gospel-books 650-800. London: Thames & Hudson. p. 110. ISBN 9780500234747.

- Gógan, Liam S. (1932). The Ardagh chalice; a description of the ministral chalice found at Ardagh in county Limerick in the year 1868. Dublin: Browne & Nolan. p. 93.

- Beaumont, Edward T. (1913). Ancient Memorial Brasses. London: Oxford University Press. p. 43.

- Taylor, Stephen (2003). The occurrence of the Fylfot-Cross in the church of Saint Mary the Virgin, Great Canfield, in the county of Essex, in relation to its wider usage at home and abroad. Cambridge: Cambridge Universal Publications. pp. 10–14. ISBN 9780954545505.

- The Fylfot File. 2006. pp. 57–62.

- Eitel, Ernest John (1884) [1873]. Buddhism : its historical, theoretical and popular aspects (3rd ed.). London: Trübner & Co. p. 119. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- Morris, Ernest (1935). Legends o' the bells; being a collection of legends, traditions, folk-tales, myths, etc., centred around the bells of all lands. London: S. Low, Marston & Co., Ltd. pp. 12–14.

- Mr. Nigel Waterson, Member for Eastbourne (12 June 1996). "273 Squadron (Badge)". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). House of Commons. col. 397–404.

- "273 Squadron RAF (Old Pattern) badge". militarybadges.co.uk. 2015. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- "Truth Swastika / Fylfot". Odinist Library. 2009. Archived from the original on 27 October 2009. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

References

- Stephen Friar (ed.), A New Dictionary of Heraldry (Alpha Books 1987 ISBN 0-906670-44-6); figure, p. 121

- James Parker, A Glossary of Terms Used in Heraldry (1894): online @ heraldsnet.org

- Thomas Wilson, The Swastika: The Earliest Known Symbol, and Its Migrations; with Observations on the Migration of Certain Industries in Prehistoric Times. Smithsonian Institution. (1896)

- Thomas Woodcock and John Martin Robinson, The Oxford Guide to Heraldry (Oxford 1990 ISBN 0-19-285224-8); figure, p. 200

External links

| Look up fylfot in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Fylfot. |

- Online versions of Wilson's book, The Swastika:

- The Swastika

- Swaztika (sic) (a scan of the original publication)

- Symbol 15:1—Symbols.com