Stilton cheese

Stilton is an English cheese, produced in two varieties: Blue, which has had Penicillium roqueforti added to generate a characteristic smell and taste, and White, which has not. Both have been granted the status of a protected designation of origin (PDO) by the European Commission, which requires that only such cheese produced in the three counties of Derbyshire, Leicestershire and Nottinghamshire may be called "Stilton". Thus cheese made in the village of Stilton, now in Cambridgeshire, cannot be sold as Stilton.

| Stilton | |

|---|---|

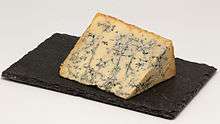

Blue Stilton | |

| Country of origin | England |

| Region, town | Derbyshire, Leicestershire, and Nottinghamshire |

| Source of milk | Cows |

| Pasteurised | Yes |

| Texture | semi-soft, crumbly, creamier with increasing age |

| Aging time | 9 weeks minimum |

| Certification | PDO[1] |

History

Frances Pawlett (or Paulet), a cheese maker of Wymondham, Leicestershire, has traditionally been credited as the one who set modern Stilton cheese's shape and style in the 1720s,[2][3] but others have also been named.[4] Early 19th-century research published by William Marshall provides logic and oral history to indicate a continuum between the locally produced cheese of Stilton, and the later development of a high turnover commercial industry importing cheese produced elsewhere, under local guidance.[5] A recipe for a Stilton cheese was published in 1726 by Richard Bradley, later first Professor of Botany at Cambridge University.[6]

Another early printed reference to Stilton cheese came from William Stukeley.[7] Daniel Defoe in his 1724 work A tour thro' the whole island of Great Britain notes, "We pass'd Stilton, a town famous for cheese, which is call'd our English Parmesan, and is brought to table with the mites or maggots round it, so thick, that they bring a spoon with them for you to eat the mites with, as you do the cheese."[8]

According to the Stilton Cheesemaker's Association, the first person to market Blue Stilton cheese was Cooper Thornhill, owner of the Bell Inn on the Great North Road, in the village of Stilton, Huntingdonshire,[9] (now an administrative district of Cambridgeshire). Tradition has it that in 1730, Thornhill discovered a distinctive blue cheese while visiting a small farm near Melton Mowbray in rural Leicestershire – possibly Wymondham.[10] He fell in love with the cheese and made a business arrangement that granted the Bell Inn exclusive marketing rights to Blue Stilton. Soon thereafter, wagonloads of cheese were being delivered there. The village stood on the Great North Road, a main stagecoach route between London and Northern England, so that Thornhill could promote sales and the fame of Stilton spread rapidly.

In 1936 the Stilton Cheesemakers' Association (SCMA) was formed to lobby for regulation to protect the quality and origin of the cheese. In 1966 Stilton was granted legal protection via a certification trade mark, the only British cheese to have received this status.[9]

Manufacture and PDO status

Blue Stilton's distinctive blue veins are created by piercing the crust of the cheese with stainless steel needles, allowing air into the core. The manufacturing and ripening process takes approximately nine to twelve weeks.

For cheese to use the name "Stilton", it must be made in one of the three counties of Derbyshire, Leicestershire and Nottinghamshire and use pasteurised local milk. Manufacturers of Stilton in these counties received protection under European Law (PDO=protected designation of origin) in 1996. Stichelton is made in the same way as Stilton cheese and uses cows' milk from a permitted county, Nottinghamshire, but the milk is unpasteurised.

By September 2016, just six dairies were licensed to make Stilton – three in Leicestershire, two in Nottinghamshire and one in Derbyshire),[11] each being subject to regular audit by an independent inspection agency accredited to European Standard EN 45011. Four of the licensed dairies are based in the Vale of Belvoir, which straddles the Nottinghamshire-Leicestershire border. This area is commonly regarded as the heartland of Stilton production, with dairies located in the town of Melton Mowbray and the villages of Colston Bassett, Cropwell Bishop, Long Clawson and Saxelbye. Another Leicestershire dairy was located in the grounds of Quenby Hall near the village of Hungarton, outside the generally accepted boundaries of the Vale of Belvoir. Quenby Hall restarted Stilton production in a new dairy in August 2005 (the old dairy dated back to the 18th century) but the business folded in 2011.[12] The former Dairy Crest-owned licensed dairy that produced Stilton at Hartington in Derbyshire was acquired by the Long Clawson dairy in 2008 and closed in 2009, with its production transferred to Leicestershire. Two former employees set up the Hartington Creamery at Pikehall in Hartington parish, which was licensed in 2014.[13]

Stilton cheese cannot be produced in Stilton village, which gave the cheese its name,[14] because it is not any of the three permitted counties, but in the administrative county of Cambridgeshire and the historic county of Huntingdonshire. The Original Cheese Company applied to Defra to amend the Stilton PDO to include the village, but the application was rejected in 2013.[15]

Stilton cheese was also manufactured in Staffordshire. The Nuttall family of Beeby, Leicestershire opened a Stilton cheese factory in Uttoxeter in 1892 to take advantage of the local milk and good transport links. However, this firm did not last long and the site became a general dairy.[16]

Characteristics

To be called "Blue Stilton", a cheese must:[17]

- be made only in the three counties of Derbyshire, Leicestershire and Nottinghamshire from local milk, which is pasteurised before use, although at peak times the milk may be drawn from elsewhere in England and Wales),

- have the traditional cylindrical shape,

- form its own crust or coat,

- be unpressed,

- contain delicate blue veins radiating from the centre,

- have a "taste profile typical of Stilton",

- and have a minimum of 48 per cent milk fat in the dry matter.

Stilton has a typical fat content of about 35% and protein content of about 23%.[17]

Similar cheeses

A number of blue cheeses are made in a similar way to Blue Stilton. These gain their blue veins and distinct flavour from the use of one or more saprotrophic fungi, such as Penicillium roqueforti and Penicillium glaucum. Since the PDO came into effect, some British supermarkets have stocked a generic "British Blue cheese". Other makers have adopted their own names and styles. Other typical British blue cheeses are Oxford Blue and Shropshire Blue. Stichelton is an English blue cheese similar to Blue Stilton, except that it does not use pasteurised milk or factory-produced rennet.

Many countries have blue cheeses. Italy, for example, has greenish blue Gorgonzola made from cows' milk. France blue cheeses such as Fourme d'Ambert from Auvergne, and made with cows' milk, and Roquefort, made with ewes' milk. Denmark produces Danish Blue Cheese. Some of the many cheese in the Netherlands are blue, such as Ruscello.[18]

Consumption

Blue Stilton is often eaten with celery or pears. It is also commonly added as a flavouring to vegetable soup, most notably to cream of celery or broccoli.[19] Alternatively, it is eaten with various crackers, biscuits and bread. It can also be used to make a blue cheese sauce to be served drizzled over a steak, or can be crumbled over a salad. Traditionally, a barley wine or port is paired with Blue Stilton, but it also goes well with sweet sherry or Madeira wine. The "uncouth" practice of scooping a hollow into the centre of a Stilton cheese and pouring the port wine into it is deprecated; nonetheless this combination has been marketed in screw-topped tubes "like toothpaste".[20][21] The cheese is traditionally eaten at Christmas.[22] The rind of the cheese forms naturally during the aging process, and is perfectly edible, unlike the rind of some other cheeses, such as Edam or Port Salut.

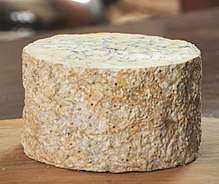

White Stilton has not had the Penicillium roqueforti mould introduced into it, which would otherwise lead to the blue veining normally associated with Stilton. It is a crumbly, creamy, open-textured cheese now extensively used as a base for blending with apricot, ginger and citrus or vine fruits to create dessert cheeses and has also been used as a flavouring for chocolate.[23]

Huntsman cheese is made with both Blue Stilton and Double Gloucester.

Dreams

A 2005 survey by the British Cheese Board reported that Stilton seemed to cause unusual dreams, with 75 per cent of men and 85 per cent of women experiencing "odd and vivid" dreams after eating a 20-gram serving of the cheese half an hour before sleeping.[24]

Cultural influence

English author G. K. Chesterton wrote a couple of essays on cheese, specifically on the absence of cheese in art. In one of his essays he recalls a time when he, by chance, visited a small town in the fenlands of England, which turned out to be Stilton. His experience in Stilton left a deep impression on him, which he expressed through poetry in his "Sonnet to a Stilton Cheese":

Stilton, thou shouldst be living at this hour

And so thou art. Nor losest grace thereby;

England has need of thee, and so have I —

She is a Fen. Far as the eye can scour,

League after grassy league from Lincoln tower

To Stilton in the fields, she is a Fen.

Yet this high cheese, by choice of fenland men,

Like a tall green volcano rose in power.

Plain living and long drinking are no more,

And pure religion reading "Household Words",

And sturdy manhood sitting still all day

Shrink, like this cheese that crumbles to its core;

While my digestion, like the House of Lords,

The heaviest burdens on herself doth lay.

This is in part a parody of William Wordsworth's sonnet "London, 1802", the opening line of which was "Milton! thou shouldst be living at this hour."

George Orwell wrote an essay, "In Defence of English Cooking", first published in the Evening Standard on 15 December 1945. While enumerating the high points of British cuisine, he touches on Stilton: "Then there are the English cheeses. There are not many of them, but I fancy that Stilton is the best cheese of its type in the world, with Wensleydale not far behind."

The Stilton Cheese Makers Association produced a fragrance called Eau de Stilton, which was "very different to the very sweet perfumes you smell wafting down the street as someone walks past you."[25]

The search for an unpasteurised Stilton cheese was a plot element of a Chef! episode titled "The Big Cheese", aired on BBC1 on 25 February 1993.

A character named G. D'Arcy "Stilton" Cheesewright appears in several of the Jeeves novels of P. G. Wodehouse.

References

- "Denomination Information White Stilton cheese; Blue Stilton cheese". Official Journal of the European Union. Retrieved 4 June 2014.

- Linford, Jenny (2008-10-20). Great British Cheeses. Penguin. pp. 208–. ISBN 978-0-7566-5100-8. Retrieved 11 March 2013.

- Weinzweig, Ari (2003-11-14). Zingerman's Guide to Good Eating: How to Choose the Best Bread, Cheeses, Olive Oil, Pasta, Chocolate, and Much More. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. pp. 286–. ISBN 978-0-547-34811-7. Retrieved 10 March 2013.

- McCartney, Stewart (2012-04-30). Popular Errors Explained. Random House. pp. 36–. ISBN 978-1-4090-2189-6. Retrieved 10 March 2013.

- Hughes, Glyn (2 Sep 2018). "The Foods of England Project: Blue Stilton Cheese". Retrieved 20 Jan 2020.

- Bradley, Richard (1726). A General Treatise of Husbandry & Gardening. pp. 117–8.

- Itinerarium Curiosum, Letter V, dated October 1722.

- Everyman's Library (London/New York: Dent/Dutton, 1928), Vol. II, p. 110.

- "Stilton Cheese: History of Stilton". stiltoncheese.com.

- Edwards, Adam (20 June 2006). "The cheese that broke the mould". Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 2010-05-24.

- "Stilton Cheese – The Stilton Producers". stiltoncheese.co.uk. Iconography Ltd.

- "Quenby Hall administrators seek buyer". meltontimes.co.uk. 22 April 2011. Retrieved 22 February 2018.

- "Say cheese! Derbyshire Stilton on sale for first time in five years". Derby Telegraph. 5 September 2014. Archived from the original on 4 June 2015. Retrieved 22 February 2018.

- Charles, Aaron-Spencer (December 28, 2011). "Cheese made in Stilton not allowed to be called Stilton – it's the law". Retrieved December 28, 2011.

- Richards, Chris (23 October 2013). "Villagers' bid to make Stilton cheese in Stilton is rejected". Daily Mirror. Archived from the original on 16 July 2014. Retrieved 22 February 2018.

- The Comprehensive Gazetteer of England & Wales, 1894–1895.

- Trott, Robert E (12 January 1994). "Product Specification". Agricultural and Rural Development DOOR. European Commission. Retrieved 24 January 2016.

- Dutch website dedicated to blue veined cheese (in Dutch).

- "Broccoli & Stilton Soup recipe". The Accidental Smallholder.

- Rubino, G (1991). "The Mediterranean Way of Eating". Rotunda. Vol. 24 no. 3. Royal Ontario Museum. p. 11.

- Layton, T. A. (1973). The cheese handbook; a guide to the world's best cheeses, over 250 varieties described, with recipes. New York: Dover Publications. pp. 116–7. ISBN 9780486229553.

- "Food – Christmas". BBC.

- "Chocolate cheese hits the shelves". Which? magazine. April 5, 2007.

- "Sweet Dreams Are Made of Cheese". 2005-09-25. Archived from the original on 2006-01-15. Retrieved 2007-07-20.

- "Stilton scent pleases cheese fans". news.bbc.co.uk. 12 May 2006.

Further reading

- Cozzolino, Laura (September 3, 2013). "5 Most Expensive Cheeses in the World". The Epoch Times. Retrieved 4 October 2013. — information about White Stilton Gold cheese, one of the most expensive cheeses in the world

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Stilton cheese. |