Thomas Bilson

Thomas Bilson (1547 – 18 June 1616) was an Anglican Bishop of Worcester and Bishop of Winchester. With Miles Smith, he oversaw the final edit and printing of the King James Bible. He is buried in Westminster Abbey in plot 232 between the tombs of Richard II and Edward III. On top of his gravestone there is a small rectangular blank brass plate (the original plate was removed to preserve it and is on display on the floor against the wall between the tombs of Richard ll and Edward lll), which says the following:—

Thomas Bilson | |

|---|---|

| Lord Bishop of Winchester | |

| |

| Province | Church of England |

| See | Winchester |

| Installed | 1597 |

| Predecessor | William Day |

| Successor | James Montague |

| Other posts | Bishop of Worcester (1596–1597) |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1547 Winchester, England |

| Died | 18 June 1616 |

MEORIAE SACRVM / HIC IACET THOMAS BILSON WINTONIENSIS NVPER EPISCOPVS / ET SERENISSIMO PRINCIPI IACOBO MAGNAE BRITTANIAE REGI /POTENTISSIMO A SANCTIORIBVS CONSILIJS QVI QVVM DEO ET / ECCLESIAE AD ANNOS VNDE VIGINTI FIDELITER IN EPISCO / PATV DESERVISSET MORTALITATE SUB CERTA SPE RESVRRECTI: /ONIS EXVIT DECIMO OCTAVO DIE MENSIS IVNIJ ANO DOMINI /M.DC XVI. AETATIS SVAE LXIX.

Translation:— Here lies Thomas Bilson formerly bishop of Winchester and counsellor in sacred matters of his serene highness King James of Great Britain who when he had served God and the church for nineteen years in the bishopric laid aside mortality in certain hope of resurrection 18 June 1616 aged 69.

Life

Years under the Tudors (1547–1603)

According to the original 'Dictionary of the National Biography' (founded in 1882 by George Smith and edited by both Sir Leslie Stephen who was Virginia Woolf's father, and Sir Sidney Lee) Thomas Bilson was the eldest son of Herman Bilson, grandson of Arnold Bilson, whose wife is said to have been a daughter of the Duke of Bavaria. Later editions highlight that William Twisse was a nephew.[1][2][3] Bilson was educated at the twin foundations of William de Wykeham, Winchester College and New College, Oxford.[4] He began to distinguish himself as a poet until, on receiving ordination, he gave himself wholly to theological studies. He was soon made Prebendary of Winchester, and headmaster of the College there until 1579 and Warden from 1581 to 1596.[5][6] His pupils there included John Owen, and Thomas James, whom he influenced in the direction of patristics.[7] In 1596, he was made Bishop of Worcester, where he found Warwick uncomfortably full of recusant Roman Catholics.[8][9] For appointment in 1597 to the wealthy see of Winchester, he paid a £400 annuity to Elizabeth I.[10]

As the Bishop of Winchester, Thomas Bilson would have resided at Winchester Palace, where today in Clink Street, Southwark, London SE1 – there is only one remaining wall of the palace – with a magnificent rose window measuring thirteen feet across. However, back in the sixteenth century, Winchester Palace was a splendorous site and would have looked very similar to the waterfront house of 'Sir Robert De Lesseps' depicted in the film Shakespeare in Love. The 700 acre Bishoprick 'see' and jurisdiction of the Bishop of Winchester included an area known as – 'The Liberty of Clink' Southwark, Bankside – which in addition to having a prison ('The Clink') also provided the site of many of the major theatres of the day, namely:

— ‘The Rose’ built in 1587 in Rose Lane where Philip Henslowe was the lessee; — ‘The Swan’ built in 1596 by Francis Langley in Paris Garden; — ‘The Globe’ re-built in 1598 by James Burbage and William Shakespeare; (a year after Thomas Bilson became the Bishop of Winchester) and — ‘The Hope’ built in 1613 by Philip Henslowe in Bear Garden.

Southwark on the south bank of the river Thames in London was very much a cash generator in those days. (Back in the sixteenth century, Southwark was in many ways like a prototype Las Vegas.) In addition to the theatres, Southwark, Bankside was also a ‘red light’ district renowned for its brothels and contained an unconsecrated graveyard for the corpses of women who had worked in them. Far from condemning the brothels, the respective bishops of Winchester, Thomas Bilson included, drew up a set of rules for their regulation and opening hours. In addition to prostitution and pick pockets, the area was also renowned for its gambling dens, skittle alleys and bear/bull baiting, most of which were run by Philip Henslowe (1550–1616) who married a wealthy widow by the name of Agnes Woodward in 1579 and it is thought that with her money Henslowe had managed to acquire interests in numerous brothels, inns, lodging houses and was also involved in dyeing, starch making and wood selling as well as pawnbroking, money lending and theatrical enterprises. With regard to his relationship with actors and playwrights Henslowe wrote in his diary:—“Should these fellowes come out of my debt I should have no rule over them.” Although Philip Henslowe was undoubtedly the main operational manager and entrepreneur behind many of Southwark’s and the ‘see of Winchester’s’ cash generating entertainment enterprises — all taxes from these activities had to be paid to Thomas Bilson the Bishop of Winchester. Indeed, in the London Public Record Office is an entry relating to William Shakespeare's unpaid tax, and carrying the annotation 'Ep (iscop)o Winton (ensi)' (to the Bishop of Winchester) – (*The Public Record Office, Exchequer, Lord Treasurers Remembrancer, Pipe Rolls, E.372/444, m. Dated 6 October 1600.) – which has led historians such as Ian Wilson in his 1993 book 'Shakespeare the Evidence' to surmise that perhaps William Shakespeare was living within the bishopric 'see' of Thomas Bilson the Bishop of Winchester at this time. However somewhat curiously, William Shakespeare's name does not appear in the church wardens' annual lists of those residents registered as having attended compulsory Easter Communion. The church wardens annual lists of residents and the compulsory attendance of Easter Communion – in effect the commencement of the new year within the Julian Calendar – provided the paranoid bureaucratic authorities – fearful of Jesuit and Catholic uprisings with a detailed census as to the political status of its citizens and as a means to assess their military and tax obligations. William Shakespeare's omission from this list and the reference to Thomas Bilson the Bishop of Winchester implies 'a relationship' between these two men which has hitherto been unexplained. – Indeed, the commonality of both men being to a large extent historical enigmas is curious in itself.

Thomas engaged in most of the polemical contests of his day, as a stiff partisan of the Church of England. In 1585, he published his The True Difference Betweene Christian Subjection and Unchristian Rebellion. This work took aim at the Jesuits and replied to Cardinal William Allen's Defence of the English Catholics (Ingoldstadt, 1584).[11] It was also a theoretical work on the "Christian commonwealth" and it enjoyed publishing success. Some historians have stated that the immediate purpose of True Difference was as much to justify Dutch Protestants resisting Philip II of Spain, as to counter the Jesuits' attacks on Elizabeth I.[12] Glenn Burgess considers that in True Difference Bilson shows a sense of the diversity of "legitimate" political systems.[13] He conceded nothing to popular sovereignty, but said that there were occasions when a king might forfeit his powers.[14] According to James Shapiro,[15] he "does his best to walk a fine line", in discussing 'political icons', i.e. pictures of the monarch.

Theological controversy

A theological argument over the Harrowing of Hell led to several attacks on Bilson personally in what is now called the Descensus controversy. Bilson's literal views on the descent of Christ into Hell were orthodox for "conformist" Anglicans of the time, while the Puritan wing of the church preferred a metaphorical or spiritual reading.[16] He maintained that Christ went to hell, not to suffer, but to wrest the keys of hell out of the Devil’s hands. For this doctrine he was severely handled by Henry Jacob and also by other Puritans. Hugh Broughton, a noted Hebraist, was excluded from the translators of the King James Bible, and became a vehement early critic. The origin of Broughton's published attack on Bilson as a scholar and theologian, from 1604,[17] is thought to lie in a sermon Bilson gave in 1597, which Broughton, at first and wrongly, thought supported his own view that hell and paradise coincided in place. From another direction the Roman Catholic controversialist Richard Broughton also attacked Anglican conformists through Bilson's views, writing in 1607.[18][19] Much feeling was excited by the controversy, and Queen Elizabeth, in her ire, commanded Bilson, "neither to desert the doctrine, nor let the calling which he bore in the Church of God, be trampled under foot, by such unquiet refusers of truth and authority."[2]

Bilson's most famous work was entitled The Perpetual Government of Christ's Church and was published in 1593. It was a systematic attack on Presbyterian polity and an able defence of Episcopal polity.[20] Following on from John Bridges,[21][22] the work is still regarded as one of the strongest books ever written in behalf of episcopacy.[2]

Courtier to James I (1603–1616)

Bilson gave the sermon at the coronation on 25 July 1603 of James VI of Scotland as James I of England. While the wording conceded something to the divine right of kings, it also included a caveat about lawful resistance to a monarch. This theme was from Bilson's 1585 book, and already sounded somewhat obsolescent.[23]

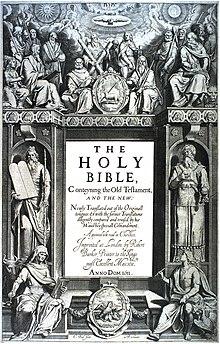

At the Hampton Court Conference of 1604, he and Richard Bancroft implored King James to change nothing in the Church of England.[24] He had in fact advised James in 1603 not to hold the Conference, and to leave religious matters to the professionals.[25] The advice might have prevailed, had it not been for Patrick Galloway, Moderator of the Scottish Assembly.[26] Later, in charge of the Authorized Version, he composed the front matter with Miles Smith, his share being the dedication.[27]

He bought the manor of West Mapledurham, near Petersfield, Hampshire, in 1605.[28] Later, in 1613, he acquired the site of Durford Abbey, Rogate, Sussex.[29]

He was ex officio Visitor of St John's College, Oxford, and so was called to intervene when in 1611 the election as President of William Laud was disputed, with a background tension of Calvinist versus Arminian. The other candidate was John Rawlinson. Bilson, taken to be on the Calvinist side, found that the election of the high-church Laud had failed to follow the college statutes.[30] He in the end ruled in favour of Laud, but only after some intrigue: Bilson had difficulty in having his jurisdiction recognised by the group of Laud's activists, led unscrupulously by William Juxon. Laud's party had complained, to the King, who eventually decided the matter himself, leaving the status quo, and instructed Bilson.[31][32]

Final years

He was appointed a judge in the 1613 annulment case of Robert Devereux, 3rd Earl of Essex and his wife Frances née Howard; with John Buckridge, bishop of Rochester, he was one of two extra judges added by the King to the original 10, who were deadlocked. This caused bitterness on the part of George Abbot, the archbishop of Canterbury, who was presiding over the nullity commission. Abbot felt that neither man was impartial, and that Bilson bore him an old grudge.[33] Bilson played a key role in the outcome, turning away the Earl of Essex's appeal to appear a second time before the commission, and sending away Henry Wriothesley, 3rd Earl of Southampton who was asking on behalf of Essex with a half-truth about the position (which was that the King had intervened against Essex).[34] The outcome of the case was a divorce, and Bilson was then in favour with Robert Carr, 1st Earl of Somerset, a favourite in the court who proceeded to marry Frances. Bilson's son Sir Thomas Bilson was nicknamed "Sir Nullity Bilson", because his knighthood followed on the outcome of the Essex annulment case.[35][36]

In August 1615 Bilson was made a member of the Privy Council.[37] In fact, though this was the high point of Bilson's career as courtier, and secured by Somerset's influence, he had been led to expect more earlier that summer. Somerset had been importunate to the point of pushiness on behalf of Bilson, hoping to secure him a higher office, and had left Bilson in a false position and James very annoyed. This misjudgement was a major step in Somerset's replacement in favour by George Villiers, said to have happened in physical terms under Bilson's roof at Farnham Castle that same August.[38][39] Bilson died in 1616 and was buried in Westminster Abbey.[2]

Legacy

It was said of him, that he "carried prelature in his very aspect." Anthony Wood proclaimed him so "complete in divinity, so well skilled in languages, so read in the Fathers and Schoolmen, so judicious is making use of his readings, that at length he was found to be no longer a soldier, but a commander in chief in the spiritual warfare, especially when he became a bishop!" Bilson is also remembered for being hawkish against recusant Roman Catholics.[40] Henry Parker drew on both Bilson and Richard Hooker in his pamphlet writing around the time of English Civil War.[41]

Bilson had argued for resistance to a Roman Catholic prince. A century later, Richard Baxter drew on Bilson in proposing and justifying the deposition of James II.[42] What Bilson had envisaged in 1585 was a "wild" scenario or counterfactual, a Roman Catholic monarch of England: its relevance to practical politics came much later.[43]

Writings

His writings took a nuanced and middle way in ecclesiastical polity, and avoided Erastian views and divine right, while requiring passive obedience to authority depending on the context.[44][45] His efforts to avoid condemning Huguenot and Dutch Protestant resisters have been described as "contortions".[46] His works included:

- The True Difference Betweene Christian Subjection and Unchristian Rebellion (1585)

- The Perpetual Government Of Christ's Church (1593)

- Survey of Christ's Sufferings for Man's Redemption and of His Descent to Hades Or Hell for Our Deliverance (1604) against the Brownist Henry Jacob[11]

References

- "The Qualifications of the King James Translators". scionofzion.com. Retrieved 12 April 2014.

- Alexander McClure. The Translators Revived 1858.

- "New Focus | That the purpose of God according to election might stand". Archived from the original on 9 November 2007. Retrieved 12 April 2014.

- Concise Dictionary of National Biography

- "Winchester – St Mary's College | A History of the County of Hampshire: Volume 5 (pp. 14–19)". british-history.ac.uk. Retrieved 12 April 2014.

- Kirby, Thomas Frederick (1888). Winchester scholars. A list of the wardens, fellows, and scholars of Saint Mary college of Winchester, near Winchester, commonly called Winchester college. London: H. Frowde.

- Mordechai Feingold, History of Universities, Volume XXII/1 (2007), p. 23.

- Patrick Collinson, The Elizabethan Puritan Movement (1982), p. 441.

- Anthony Boden, Denis Stevens, Thomas Tomkins: The Last Elizabethan (2005), p. 73.

- Hugh Trevor-Roper, William Laud (2000 edition) p. 11.

- http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/encyc02.html?term=Bilson,%20Thomas

- Hugh Dunthorne, The Netherlands' as Britain school of Revolution, p. 141, in Royal and Republican Sovereignty in Early Modern Europe: Essays in Memory of Ragnhild Hatton (1997).

- Glenn Burgess, The Politics of the Ancient Constitution: An Introduction to English Political Thought, 1603–1642 (1993), pp. 104–5.

- Michael Brydon, The Evolving Reputation of Richard Hooker: An Examination of Responses, 1600–1714 (2006), pp. 132–3.

- James Shapiro, 1599: A Year in the Life of William Shakespeare (2005), p. 177.

- Bruce Gordon, Peter Marshall, The Place of the Dead: Death and Remembrance in Late Medieval and Early Modern Europe (2000), pp. 118–9.

- Declaration of general corruption, of religion, Scripture, and all learninge: wrought by D. Bilson.

- Willem Nijenhuis, Adrianus Saravia (c. 1532 – 1613): Dutch Calvinist, First Reformed Defender of the English Episcopal Church Order on the Basis of the Ius Divinum (1980), p. 182.

- Charles W. A. Prior, Defining the Jacobean Church: The Politics of Religious Controversy, 1603–1625 (2005), pp.49–50 and note.

- "Outlines of the History of the Theological Literature of the Church of England (1897)". anglicanhistory.org. Retrieved 12 April 2014.

- Robert Zaller, The Discourse of Legitimacy in Early Modern England (20070, p. 342.

- Ray Shelton. "ENGLAND". fromdeathtolife.org. Archived from the original on 22 August 2012. Retrieved 12 April 2014.

- Peter E. McCullough, Sermons at Court: Politics and Religion in Elizabethan and Jacobean Preaching (1998), pp. 104.

- W. B. Patterson, King James VI and I and the Reunion of Christendom (1997), p. 104.

- Alan Stewart, The Cradle King: A Life of James VI & I (2003), p. 191.

- Collinson, p. 451.

- Alister McGrath, In The Beginning: The Story of the King James Bible (2001), p. 188, p. 210.

- "Parishes – Buriton | A History of the County of Hampshire: Volume 3 (pp. 85–93)". british-history.ac.uk. Retrieved 12 April 2014.

- "Rogate | A History of the County of Sussex: Volume 4 (pp. 21–27)". british-history.ac.uk. Retrieved 12 April 2014.

- Trevor-Roper, p. 43.

- Thomas A. Mason, Serving God and Mammon: William Juxon, 1582–1663, Bishop of London, Lord High Treasurer of England, and Archbishop of Canterbury (1985), p. 27.

- Kenneth Fincham, Early Stuart Polity p. 188 in The History of the University of Oxford (1984).

- Anne Somerset, Unnatural Murder: Poison at the Court of James I, pp. 159–160.

- Somerset, p. 164.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 8 January 2011. Retrieved 5 October 2008.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Somerset, p. 168.

- "1eng". philological.bham.ac.uk. Retrieved 12 April 2014.

- Alan Stewart, The Cradle King: A Life of James VI & I (2003), p. 271.

- Somerset, p. 286.

- Michael C. Questier, Conversion, Politics and Religion in England, 1580–1625 (1996), note p. 189.

- Michael Mendle, Henry Parker and the English Civil War: The Political Thought of the Public's 'Privado' (2003), p. 63.

- William M. Lamont, Richard Baxter and the Millennium (1979), p. 29.

- William Lamont, Puritanism and Historical Controversy (1996), pp. 56–8.

- Whitney Richard David Jones, The Tree of Commonwealth, 1450–1793 (2000), p. 99.

- Irving Ribner, The English History Play in the Age of Shakespeare (2004), p. 307.

- Lisa Ferraro Parmelee, Good Newes from Fraunce: French Anti-league Propaganda in Late Elizabethan England (1996), p. 112.

Further reading

- William M. Lamont, "The Rise and Fall of Bishop Bilson", The Journal of British Studies, Vol. 5, No. 2 (May 1966), pp. 22–32 online

External links

| Church of England titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Richard Fletcher |

Bishop of Worcester 1596–1597 |

Succeeded by Gervase Babington |

| Preceded by William Day |

Bishop of Winchester 1597–1616 |

Succeeded by James Montague |