Statesboro, Georgia

Statesboro is the largest city and county seat of Bulloch County, Georgia, United States,[6] located in the southeastern part of the state.

Statesboro | |

|---|---|

| Statesboro, Georgia | |

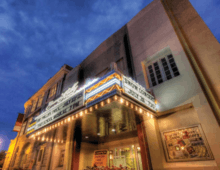

From top to bottom left to right: The Bulloch County Courthouse and Averitt Center for the Arts, Splash in the Boro Water Park, Campus Georgia Southern University, the Emma Kelly Theater | |

Seal | |

| Nickname(s): The Boro | |

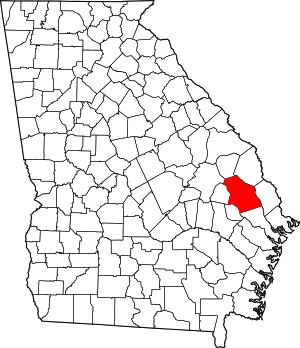

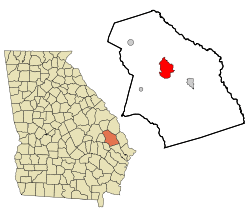

Location in Bulloch County and the state of Georgia | |

Statesboro Location in the United States | |

| Coordinates: 32°26′43″N 81°46′45″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Georgia |

| County | Bulloch |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Jonathan McCollar |

| Area | |

| • City | 15.20 sq mi (39.36 km2) |

| • Land | 14.89 sq mi (38.56 km2) |

| • Water | 0.31 sq mi (0.80 km2) |

| Elevation | 253 ft (77 m) |

| Population | |

| • City | 28,422 |

| • Estimate (2019)[3] | 32,954 |

| • Density | 2,213.31/sq mi (854.54/km2) |

| • Metro | 71,214 (US: 95th) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| ZIP codes | 30458-30461 |

| Area code(s) | 912 |

| FIPS code | 13-73256[4] |

| GNIS feature ID | 0323541[5] |

| Website | City of Statesboro |

Statesboro is home to the flagship campus of Georgia Southern University and is part of the Savannah–Hinesville–Statesboro Combined Statistical Area.[7] As of 2018, the Statesboro Micropolitan Statistical Area, which consists of Bulloch County, had an estimated population of 74,722.[8] The city had an estimated 2019 population of 32,954.[9] Statesboro is the largest Micropolitan Statistical Area in Georgia. It is the largest city in the Magnolia Midlands Region.

The city was chartered in 1803, starting as a small trading community providing basic essentials for surrounding cotton plantations. This drove the economy throughout the 19th century, both before and after the U.S. Civil War.

In 1906, Statesboro and area leaders joined together to bid for and win the First District A&M School, a land grant college that eventually developed into Georgia Southern University.

Statesboro inspired the blues song "Statesboro Blues", written by Blind Willie McTell in the 1920s, and covered in a well-known version by the Allman Brothers Band.[10]

In 2017, Statesboro was selected in the top three of the national America's Best Communities competition and was named one of nine Georgia "live, work, play" cities by the Georgia Municipal Association.[11][12]

History

In 1801, George Sibbald of Augusta donated a 9,301-acre (37.64 km2) tract for a centrally located county seat for the growing agricultural community of Bulloch County. The area was developed by white planters largely for cotton plantations that were worked by black slave labor. In December 1803, the Georgia legislature created the town of Statesborough. The community most likely was named after the notion of states' rights, an issue central in the 1800 United States presidential election.[13] In 1866 the state legislature granted a permanent charter to the city, changing the spelling of its name to the present "Statesboro."

During the Civil War and General William T. Sherman's famous March to the Sea through Georgia, a Union officer asked a saloon proprietor for directions to Statesboro. The proprietor replied, "You are standing in the middle of town,"[14] indicating its small size. The soldiers destroyed the courthouse, a log structure that doubled as a barn when court was not in session. After the Civil War, the small town began to grow, and Statesboro has developed as a major town in southeastern Georgia. Many freedmen stayed in the area, working on plantations as sharecroppers and tenant farmers.

Following the Reconstruction era, racial violence of whites against blacks increased. In the era from 1880 to 1930, Georgia had the highest rate of lynchings of any state in the nation.[15] Among them were three black men who were lynched and burned to death on August 16, 1904, near Statesboro. A fourth man was lynched later in the month in Bulloch County. After a white farm family was killed, the white community spread unfounded rumors of black clergy urging blacks to violence against whites, and more than twelve black men were arrested in this case.[16]

Paul Reed and Will Cato were convicted of the Hodge family murders by an all-white jury and sentenced to death on August 16, 1904, but they were abducted that day from the courthouse by a lynch mob and brutally burned to death. Handy Bell, another suspect, was lynched and burned by a mob that night.[17] White violence against blacks did not end; both men and women were physically attacked on the streets. Area newspaper coverage of the trial and lynching had been sensationalized, arousing anger, and two more black men were lynched in August 1904: Sebastian McBride in Portal, another town in Bulloch County, and A.L. Scott in Wilcox County.[18][19][16]

To escape oppression and violence, many African Americans left Statesboro and Bulloch County altogether, causing local businessmen to worry about labor shortages in the cotton and turpentine industries.[18] African Americans made a Great Migration from the rural South to northern cities in the first half of the 20th century.[16] Local effects can be seen in the drop in Statesboro population growth from 1910 to 1930 on the census tables below in the "Demographics" section.

Around the turn of the century, new businesses in Statesboro included stores and banks built along North, East, South, and West Main streets. In 1908, Statesboro led the world in sales of long-staple Sea Island Cotton, a specialty of the Low Country.

Mechanization of agriculture decreased the need for some farm labor. After the boll weevil destroyed the cotton crop in the 1930s, farmers shifted to tobacco. The insect had invaded the South from the west, disrupting cotton cultivation throughout the region. By 1953, however, more than 20 million pounds of tobacco passed through warehouses in Statesboro, then the largest market of the "Bright Tobacco Belt" spanning Georgia and Florida.

The 1906 First District Agricultural & Mechanical School at Statesboro was developed as a land grant college, initiated by federal legislation to support education. Its mission shifted in the 1920s to teacher training; and in 1924 it was renamed as the Georgia Normal School. With expansion of the curriculum to a 4-year program, it was renamed as the South Georgia Teachers College in 1929. Other name changes were to Georgia Teachers College in 1939, and Georgia Southern College in 1959. After this period, it became racially integrated and with development of graduate programs and research in numerous fields, since 1990 it has had university status as Georgia Southern University.

Economy

The economy of Statesboro is based on education, manufacturing, and agribusiness sectors. Statesboro serves as a regional economic hub and has more than one billion dollars in annual retail sales.[20]

Georgia Southern University is the largest employer in the city, with 6,700 regional jobs tied directly and indirectly to the campus.

Agriculture is responsible for $100 million in annual farm gate revenues.[21]

Statesboro is home to multiple manufacturing facilities. Statesboro Briggs & Stratton Plant is the third-largest employer in the region with 950 employees.[22]

The Development Authority of Bulloch County retains over 100 acres of GRAD (Georgia Ready for Accelerated Development) land at the Gateway Industrial Park. Southern Gateway Park is a newly developed 200-acre tract located at the intersection of U.S. 301 and Interstate 16 in close proximity to the Court of Savannah. Southern Gateway is served by municipal water, sewer and natural gas lines.[23]

GAF, the largest privately owned roofing manufacturer in North America, relocated to Statesboro in the early 21st century.[21]

Geography

Statesboro is located at 32°26′43″N 81°46′45″W (32.445147, -81.779234).[24] The city is located in southeastern Georgia along U.S. Routes 80, 25, and 301. US 80 runs northwest to southeast through the city, leading southeast 58 mi (93 km) to Savannah and west-northwest 37 mi (60 km) to Swainsboro. US 25 and 301 run concurrently through the center of town and split upon their junction with US 80, leading south 12 mi (19 km) to Interstate 16 at exit 116. US 25 leads north 29 mi (47 km) to Millen and US 301 north 24 mi (39 km) to Sylvania.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 13.9 square miles (35.9 km2), of which 13.5 square miles (35.0 km2) is land and 0.35 square miles (0.9 km2), or 2.60%, is water.[25] The city is in the coastal plain region, or Low Country, of Georgia, so it is mainly flat with a few small hills. With an elevation of 250 feet (76 m), the downtown area is one of the highest places in Bulloch County. Pine, oak, magnolia, dogwood, palm, sweetgum, and a variety of other trees can be found in the area.

Climate

Statesboro has a humid subtropical climate, according to the Köppen classification. The city experiences very hot and humid summers with average July highs of about 91 degrees and lows around 70. Afternoon thunderstorms associated with the summer heat and humidity can spawn from time to time. Winters are mild with average January highs of 58 degrees and lows of 36 degrees.[26] Winter storms are rare, but they happen periodically, the most recent being an ice storm in January 2018. On February 12, 2010, approximately two inches of snow fell on the city.[27]

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1870 | 33 | — | |

| 1880 | 29 | −12.1% | |

| 1890 | 425 | 1,365.5% | |

| 1900 | 1,197 | 181.6% | |

| 1910 | 2,529 | 111.3% | |

| 1920 | 3,807 | 50.5% | |

| 1930 | 3,996 | 5.0% | |

| 1940 | 5,028 | 25.8% | |

| 1950 | 6,097 | 21.3% | |

| 1960 | 8,356 | 37.1% | |

| 1970 | 14,616 | 74.9% | |

| 1980 | 14,866 | 1.7% | |

| 1990 | 15,854 | 6.6% | |

| 2000 | 22,698 | 43.2% | |

| 2010 | 28,422 | 25.2% | |

| Est. 2019 | 32,954 | [3] | 15.9% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[28] | |||

As of the census of 2010, there were 28,422 people, 8,560 households, and 3,304 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,812.9 people per square mile (700.0/km2). There were 9,235 housing units at an average density of 737.6 per square mile (284.8/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 53% White, 39.4% African American, 0.1% Native American, 2.8% Asian,1.6% from other races, and 3% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 2.2% of the population.[29]

There were 8,560 households, out of which 17.9% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 21.9% were married couples living together, 13.5% had a female householder with no husband present, and 61.4% were non-families. 31.4% of all households were made up of individuals, and 7.3% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.27 and the average family size was 2.93.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 14.3% under the age of 18, 48.7% from 18 to 24, 16.6% from 25 to 44, 11.3% from 45 to 64, and 9.2% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 22 years. For every 100 females, there were 88.6 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 87.3 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $19,016, and the median income for a family was $35,391. Males had a median income of $29,132 versus $20,718 for females. The per capita income for the city was $12,585. About 20.5% of families and 42.6% of the population were below the poverty line, including 33.9% of those under age 18 and 21.4% of those age 65 or over.

Education

Higher education

Georgia Southern University is the city's principal institution of higher learning. The university, a unit of the University System of Georgia, was founded as the First District Agricultural and Mechanical School in 1906 as a land grant college, open only to white students. On July 1, 1990, it became the fifth university of the University System, and as of 2015 is a comprehensive residential university of nearly 20,000 students. The university's graduate programs are offered on campus, at satellite centers, and by distance and on-line delivery. For the past decade, the university has combined a capital building program with beautification of the nearly 700-acre (2.8 km2) campus.

The university facilities include a museum of cultural and natural history, a botanical garden, and a center for wildlife education located within the campus grounds. The university's Division I athletic teams, the Georgia Southern Eagles, compete in the Sun Belt Conference.

Two community colleges are also located in Statesboro. East Georgia State College, a University System of Georgia college based in the nearby city of Swainsboro, operates a satellite campus in Statesboro. Ogeechee Technical College is a part of the Technical College System of Georgia, providing technical and adult education to area students. Both schools are located on U.S. Highway 301 South, outside of the city limits and approximately 3 miles (5 km) from the campus of Georgia Southern.

Bulloch County School District

The Bulloch County Board of Education runs the public school district in Statesboro. The largest school in the city is Statesboro High School. Other public schools include Southeast Bulloch High School, William James Middle School, Langston Chapel Middle School, Southeast Bulloch Middle School, Julia P. Bryant Elementary School, Sallie Zetterower Elementary School, Mattie Lively Elementary School, Langston Chapel Elementary School, and Mill Creek Elementary School. Private schools include Bulloch Academy, Trinity Christian School, and Bible Baptist Christian School. The Charter Conservatory for Liberal Arts and Technology, part of the CCAT public school district, is a charter school located within the city limits. In 2016 CCAT was renamed Statesboro STEAM - College, Careers, Arts, & Technology Academy.

Arts and Culture

The culture of Statesboro reflects a blend of both its southern heritage and college town identity.[30]

The city has developed a unique culture, common in many college towns, that coexists with the university students in creating an art scene, music scene and intellectual environment. Statesboro is home to numerous restaurants, bars, live music venues, bookstores and coffee shops that cater to its creative college town climate.[31]

Statesboro's downtown was named one of eight "Renaissance Cities" by Georgia Trend magazine.[32] The downtown area is currently undergoing a revitalization. The Old Bank of Statesboro and Georgia Theater have been adapted with renovation for the David H. Averitt Center for the Arts.[33] It houses the Emma Kelly Theater, named after the local singer, known as the "Lady of 6,000 Songs".[10] The center also contains art studios, conference rooms and an exhibition area. Downtown Statesboro has been featured in several motion pictures including Now and Then (1995) as well as 1969.[34] Georgia Southern offers a variety of cultural options available both for the university and the wider community: the Georgia Southern Symphony, the Georgia Southern Planetarium, Georgia Southern Museum, and the Botanical Gardens at Bland Cottage.[35] Touring groups appear at the Performing Arts Center, and also featured are shows put on by Georgia Southern students and faculty.

Mill Creek Regional Park is a large outdoor recreational facility with athletic fields and a water park, Splash in the Boro.[36]

Sports

Georgia Southern Eagles

Georgia Southern University Eagles field 17 varsity teams in the Division I Football Bowl Subdivision (FBS) and are members of the NCAA Division I Sun Belt Conference.

[37] Prior to joining the Sun Belt Conference in 2014, the Eagles were members of the Trans America Athletic Conference (presently known as the Atlantic Sun Conference) and the Southern Conference. During their time at the Football Championship Subdivision (FCS/I-AA) level, the Eagles football team won an unprecedented six national championships.

Tormenta FC

South Georgia Tormenta FC fields a professional team in USL League One, the third tier of the American Soccer Pyramid. The club's inaugural season was the 2016 season. Currently, games are played at Eagle Field. There are plans to build a new stadium in the near future.[38]

Media

Statesboro is served by a variety of media outlets in print, radio, television, and the Internet. Statesboro Magazine is the community's premier quality of life publication. The local newspaper is the Statesboro Herald, a daily with a circulation of about 6,000. Other newspapers include the George-Anne produced by Georgia Southern University students, Connect Statesboro, a weekly entertainment publication, and the E11eventh Hour, a twice-a-month entertainment publication. Radio stations include WHKN, WMCD, WPMX, WPTB, WWNS, and WVGS. Statesboro Business Magazine offers Statesboro and area business news, articles, features, jobs, real estate listings and other area business information and reviews.

StatesboroHerald.com has received numerous state[39] and national awards[40] from the newspaper industry for online innovation.

Infrastructure

Hospitals

- East Georgia Regional Medical Center

- Willingway Hospital

Transportation

Airports

Approximately 3 miles (5 km) outside of Statesboro is the Statesboro-Bulloch County Airport, which can accommodate private aircraft but does not have a control tower or commercial flights. Most travelers use the nearby Savannah/Hilton Head International Airport, which is located 45 miles (72 km) to the east and is served by eight commercial airlines. Statesboro is about three hours by highway from the major Hartsfield–Jackson Atlanta International Airport.

Highways

Interstate 16 is located 10 miles (16 km) to the south of Statesboro. Statesboro is also served by three U.S. highways: U.S. Highway 301, which runs north-south through the city, U.S. Highway 25, which runs northwest-south through the city, and U.S. Highway 80, which is the main east-west route through the city. The Veterans Memorial Parkway (Highway 301 Bypass and Highway 25 Bypass) forms a near circle around the city.

U.S. Routes:

State Routes:

Pedestrians and cycling

- S&S Greenway Trail

Rail

Rail service for freight is provided by Norfolk Southern Railway.

Notable people

- Jason Childers (born 1975), Major League Baseball relief pitcher

- Berry Avant Edenfield, United States District Court judge and Georgia State Senator

- Dale Eggeling (born 1954), golfer, winner of three LPGA Tour events

- FATBOI (born 1971), Music Producer and Engineer; Atlanta trap, Hip-hop

- Sutton Foster (born 1975), Broadway star, 2-time Tony Award winner

- Joey Hamilton (born 1970), retired Major League Baseball player

- Martha Hayslip, player in All-American Girls Professional Baseball League[41]

- Margie Hendrix (1935-1973), singer of Ray Charles Robinson Raelettes, member of The Cookies girl group, solo recording artist

- Justin Houston (born 1989), linebacker for the Kansas City Chiefs

- Emma Kelly (1918–2001), pianist

- Danny McBride (born 1976), actor, Pineapple Express and Eastbound & Down

- Jeremy Mincey (born 1983), defensive end for Dallas Cowboys

- Blind Willie McTell (1901–1959), blues musician, composed "Statesboro Blues"[42]

- Adrian Peterson (born 1979), former running back for Chicago Bears, Walter Payton Award winner who earned degree from Georgia Southern University in 2001 and helped win 1999 and 2000 National Championships

- Marty Pevey (born 1961), current manager of Iowa Cubs, Triple A affiliate of Chicago Cubs

- Commander William M. Rigdon, USN (1904–1991), assistant Naval Aide in White House, 1942–53; served throughout Presidency of Harry S. Truman

- John Rocker, Major League baseball relief pitcher

- Erk Russell (1926–2006), college football coach

- Lindsay Thomas, lived in Statesboro while serving in the United States House of Representatives.[43]

- DeAngelo Tyson (born 1989), defensive end, Baltimore Ravens

- Rashad Wright (born 1982), basketball point guard

Points of interest

- Georgia Southern Botanical Garden

- Georgia Southern University

- J. I. Clements Stadium

- Mill Creek Recreational Park

- Paulson Stadium

- Splash in the Boro

- Statesboro Mall

References

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 9, 2020.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2014-10-16.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. 2007-10-25. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on 2011-05-31. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- https://www.usg.edu/institutions "University System of Georgia _ University System of Georgia.html."Accessed 2018-2-19.

- "U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Bulloch County, Georgia; Buckeye city, Arizona; Statesboro city, Georgia". Census Bureau QuickFacts. Retrieved 12 July 2018.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- Statesboro, Georgia Convention and Visitors Bureau Archived March 24, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- Taisha White; Tandra Smith. "Statesboro places in America's Best Communities contest". Thegeorgeanne.com. Retrieved 12 July 2018.

- Krakow, Kenneth K. (1975). Georgia Place-Names: Their History and Origins (PDF). Macon, GA: Winship Press. p. 212. ISBN 0-915430-00-2.

- "Bullochhistory - Timeline". Bullochhistory.com. Retrieved 12 July 2018.

- Meyers, Christopher C (2006). ""Killing Them by the Wholesale": A Lynching Rampage in South Georgia". The Georgia Historical Quarterly. JSTOR. 90 (2): 214–235. Retrieved 14 May 2013.

- Charlton Moseley and Frederick Brogdon, Review: "A Lynching at Statesboro: The Story of Paul Reed and Will Cato", The Georgia Historical Quarterly Vol. 65, No. 2 (Summer, 1981), pp. 104-118, via JSTOR; accessed 29 July 2016

- Pittsburg Press, 17 August 1904; accessed 29 July 2016

- Jenel Few, "Racial strife" Archived 2015-06-01 at the Wayback Machine, Savannah Morning News, 20 August 2000; accessed 29 July 2016

- Ralph Ginzburg, 100 Years of Lynching, Black Classic Press (1967/reprint paperback 1996); W. Fitzhugh Brundage, Lynching in the New South, Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1993

- "Statesboro, Bulloch County: Good Timing", Georgia Trend, July 2010

- "Statesboro/Bulloch County: Brisk Business - Georgia Trend". Georgiatrend.com.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-04-20. Retrieved 2015-04-11.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Shivers, David. " Statesboro | Bulloch County: History Meets High-Tech", Georgia Trend, 1 March 2016. Retrieved on 14 September 2019.

- "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (G001): Statesboro city, Georgia". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved November 7, 2013.

- "Average Weather for Statesboro, GA - Temperature and Precipitation". Weather.com. Retrieved 12 July 2018.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-09-30. Retrieved 2013-06-17.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- "American FactFinder". Factfinder.census.gov. Archived from the original on 2020-02-11. Retrieved 2012-10-17.

- "Georgia Southern - Graduate Admissions". Cogs.georgiasouthern.edu. Retrieved 2012-10-17.

- "Visit Statesboro". Statesboro Convention and Visitors Bureau. Retrieved 31 October 2013.

- "Georgia's Renaissance Cities - Georgia Trend". Georgiatrend.com.

- "New arts center opens today in Statesboro : Savannah Morning News". Savannahnow.com. 2004-09-08. Archived from the original on 2012-09-17. Retrieved 2012-10-17.

- "Now and Then (1995)". IMDb.com.

- "Attractions", Georgia Southern University

- "Mill Creek Regional Park" Archived October 9, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- "Georgia Southern at a Glance | Newsroom | Georgia Southern University". University Newsroom. 2013-05-24. Retrieved 2019-09-14.

- "Tormenta stadium in advanced planning stages". www.statesboroherald.com.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-07-22. Retrieved 2010-08-25.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Inland Press Association > Contests > Contest Results". 15 April 2013. Archived from the original on 15 April 2013.

- "Martha Hayslip AAGPBL Player/Profile". Aagpbl.org. Archived from the original on 2014-06-29. Retrieved 2012-10-17.

-

Bastin, Bruce (1995). Red River Blues: The Blues Tradition in the Southeast. University of Illinois Press. p. 129. ISBN 978-0-252-06521-7.

"Statesboro, Georgia was my real home." McTell to John Lomax in 1940 interview

- Barone, Michael; Ujifusa, Grant (1987). The Almanac of American Politics 1988. National Journal. p. 291.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Statesboro, Georgia. |

- City of Statesboro official website

- Statesboro at Georgia.gov

- Statesboro Convention and Visitors Bureau

- Statesboro 360, events and entertainment listings

- Averitt Center for the Arts

- Center for Wildlife Education and Lamar Q. Ball Raptor Center

- Georgia Southern University

- Red Fern Plantation

- Historic Statesboro Photographs Collection from Georgia Southern University

- First Baptist Church of Statesboro historical marker

- New Hope Methodist Church historical marker