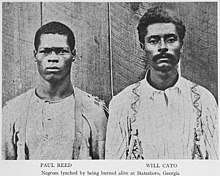

Lynching of Paul Reed and Will Cato

The lynching of Paul Reed and Will Cato occurred in Statesboro, Georgia on August 16, 1904. Five members of a white farm family, the Hodges, had been murdered and their house burned to hide the crime. Paul Reed and Will Cato, who were African-American, were tried and convicted for the murders. Despite militia having been brought in from Savannah to protect them, the two men were taken by a mob from the courthouse immediately after their trials, chained to a tree stump, and burned. In the immediate aftermath, four more African-Americans were shot, three of them dying, and others were flogged.

Murder of Hodges family

Henry Hodges was a farmer in Bulloch County, Georgia, living about 6 miles (9.7 km) from Statesboro, the county seat. His farm house burned down on the night of Thursday, July 28, 1904. The next day, the bodies of Hodges, his wife Claudia, their nine-year old daughter Kitty Corrine, two-year old son Harmon, and six-month old son Talmadge were found in the burned out house. The remains of the five victims were buried in a single coffin the next day.[1][2]

Even while the house was still burning, neighbors who arrived during the night discovered Henry Hodges' hat, signs of a struggle, and puddles of blood a short distance from the house. In the morning, footprints of four men, one of whom was barefoot, were found around the house. Dogs were brought, but were unable to track the men very far. Two shoes were found nearby, a brogan and a dress shoe, which a neighbor identified as belonging to pairs of shoes he had bought for an African-American tenant on his farm, Paul Reed. A knife, also identified as belonging to Reed, was found nearby. Several strands of hair, believed to be from Claudia Hodges, were stuck in tar on the heel of one shoe.[3]

The next day, a group of men from the area searched Reed's house. The unofficial posse found shoes matching the ones found near the Hodges' house, one in Reed's house, and the other under the house. The shoes found near the Hodges' house had shoe laces cut from a calico material, and a bolt of matching material was found in Reed's house. A pair of pants found at Reed's house had what appeared to be blood in a pocket. While Reed acknowledged that the shoes were his, he claimed that the blood in his pocket was from a dead partridge he had placed there, and he denied any involvement in the murder of the Hodges family. The sheriff subsequently arrested Paul Reed and his wife, Harriett.[4]

Harriett Reed's account

While in custody, Harriett Reed gave a statement to the sheriff that contained contradictions and unverified claims, but which implicated her husband and a neighbor, Will Cato, in the murders of the Hodges. By Harriett's account, her husband and Cato believed that Hodges had buried money behind his chicken coop. The two men had gone to the Hodges' farm on the preceding Saturday night to dig up the money, but had been discovered. They were able to convince Hodges that they were just passing by on the way to a store when a snake had grazed Cato, and had been seeking turpentine to put on the wound.[5]

Harriett Reed further said that her husband and Cato had returned to the Hodges' farm on Thursday night to again search for the buried money, but had once again been discovered by Hodges. He struggled with the would-be robbers, and his wife, Claudia, came to his aid. Both Henry and Claudia Hodges were killed by Reed and Cato. The men then moved the bodies into the house and fled. Later that night Reed and Cato returned to the farm intending to search the house for money, and then to burn it, in order to destroy evidence of the murders. They discovered the nine-year old Kitty Corinne hiding in the house and killed her. Harriett Reed's statement included the detail that Kitty Corinne had offered to give a nickle to Reed and Cato if they would spare her life. After killing the girl, the two men spread kerosene around the house and set it on fire, leaving the two young boys to burn alive in the fire.[5]

Sensational reports

Word of Harriett Reed's confession quickly spread in the community. Fifteen African-American men were brought in to the sheriff's office for questioning, but public opinion focused on Reed and Cato. Regional newspapers, the Savannah Morning News and the Augusta Chronicle, presented sensational accounts. As coins and a gold ring were found next to Claudia Hodges' body, the papers dismissed robbery as a motive for the murders, and implied acts that would imflame the situation. The papers claimed that the "flames concealed a darker crime", and that a "nameless offense" had been committed, implying that both Claudia and Kitty Corrine Hodges had been raped.[6] This invoked the Southern white image of the "African-American rapist beast". In the last years of the 19th century, Southern whites were being told that African-American men were increasingly raping white women, and that all African-American men born since emancipation were potential rapists. Jim Crow laws and lynching were therefore justifible measures to protect white women.[7] A contemporary northern reporter, Ray Stannard Baker, in writing about the Statesboro murders and lynchings, distinguished two classes of African-Americans, the "self-respecting, resident negro" and the "worthless negroes". Baker also recounts that many white men in Bulloch County believed that it was not safe for their female relatives to travel even short distances alone, or to be outside at night.[8]

Reed and Cato were also associated with the turpentine industry, a major employer in Bullock County. Although Reed was a tenant farmer and Cato a farm laborer at the time, they had previously worked in turpentine camps in the area. The need for seasonal laborers in the turpentine camps attracted young African-American workers from outside of the county. Many whites considered the itinerant workers in those camps to be "shiftless and disruptive", raising the level of vice and crime in the area. The Statesboro News reported that the "good farmers" of the county had been awakened by the Hodges' murders "to the fact that they were living in constant danger and that human vampires lived in their midst, only awaiting the opportunity to blot out their lives by murder and the torch."[9] While Reed was a native of Bulloch County, Cato was from South Carolina, and had first come to Bulloch County to work in a turpentine camp.[10]

Changing stories

There was talk in Statesboro of lynching Reed and Cato, and the sheriff moved them to the jail in Savannah. After being moved to Savannah, Reed made a statement admitting to being a lookout for John Hall and Sank Tolbert, both of whom worked for a company in Statesboro. Reed said that Hall had planned the robbery and murder. Reed also said that Cato had not been involved in the crime. After a few days, Reed changed his story, saying again that he had been a lookout, but that Will Rainey and Cato had committed the crime.[11]

Reed next blamed the crimes on the "Before Day Club", a group of African-Americans dedicated to robbing and killing whites. This time, Reed said he and Cato committed the crime, while Dan Young served as the lookout. At trial, Reed changed his story again, claiming that he had served as lookout, and that the murders were committed by Cato, Hall, Rainey, Handy Bell, and "the Kid". All of the supposed participants in the crime named by Reed were arrested. The story of Reed's claim that the Before Day Club was responsible for the murder of the Hodges family quickly spread. Before Day Clubs were soon discovered in other places in Georgia, Alabama and Virginia. The excitement about, and belief in, the Before Day Clubs eventually subsided, and the Statesboro News later acknowledged that such clubs "probably don't exist."[12]

Indictment and trial

A coroner's jury met on August 1 and 2. Testimony was taken from Harriett Reed and Ophelia Cato, Will's wife, and from neighbors who had helped investigate the murders. The jury indicted Paul Reed and Will Cato, but released most of the other suspects. Harriett Reed, Ophelia Cato and Handy Bell were held as witnesses. Many people in the white community felt that Bell should have also been indicted. With calls from the public for an immediate trial, Superior Court Judge Alexander Daley set August 15, 1904 as the trial date. Reed and Cato were given separate trials so that Harriett Reed could testify against Will Cato and Ophelia Cato could testify against Paul Reed. Talk of lynching Reed and Cato spread through Statesboro, with a belief that they would have already been lynched if they had not been moved to Savannah. Telegrams offering aid in lynching the two men were received from other counties. The Statesboro News called for hanging the "devils" in public. A photography studio advertised photos of the murdered Hodges family. The Savannah and Statesboro Railway offered special excursion fares to attend the trial. As the date for the trial approached, Statesboro mayor George M. Johnson contacted Georgia governor Joseph M. Terrell to request militia to prevent the lynching of Reed and Cato. The governor ordered the Savannah-based Oglethorpe Light Infantry of the First Infantry Regiment, Georgia State Troops, under Captain Robert M. Hitch, to Statesboro. Captain Hitch also took command of a Statesboro-based company of the Georgia Militia, for a total of 115 men under his command. [13]

The troops from Savannah arrived in Statesboro the morning of August 15. Cato's trial was on the afternoon of August 15. The militia escorted Reed and Cato to the county courthouse for Cato's trial that afternoon. Although Cato was the defendant, the testimony was primarily about Reed's role in the crime. Cato denied participating in the crime. He testified that Reed and three other men had told him about their plan to rob Hodges, but Cato said he had refused to join them. The jury found Cato guilty after eight minutes of deliberation. The militia escorted Reed and Cato back to the jail after the trial. The troops guarded the jail that night while groups of men, some of whom had been drinking, wandered through the town's streets, at one point fruitlessly calling for Judge Daley to speak to them. The next morning Reed and Cato were returned by the militia to the courthouse for Reed's trial. Reed claimed that he had loaned his shoes, which were found at the Hodges' farm, to another member of the Before Day Club. He admitted to standing watch while other members of the club went to rob Hodges, and said he had run away and hid himself when he heard the murders being committed. The jury quickly found Reed guilty. Judge Daley sentenced both men to be hanged on September 9.[13]

A mob seizes Reed and Cato

Newspapers had predicted that Reed and Cato would be lynched as soon as the trials were over, but the number of people in the courtroom and around the courthouse was smaller for Reed's trial than had been the case for Cato's trial the day before. The court officials thought that the danger of a lynching was therefore lower, but decided it would still be safer to take the convicted men to Savannah. Before Reed and Cato could be moved, a crowd gathered outside of and on the lower floor of the courthouse. Captain Hitch assigned half of his force to guard the stairs leading to the courtroom on the second floor. Captain Hitch, Judge Daley, Mayor Johnson, the sheriff and the Reverend Harmon Hodges, the brother of murder victim Henry Hodges, tried to talk to the mob, but were shouted down. The officials were unable to call Savannah for help as the telephone lines had been cut.[14]

The crowd pressed to reach the second floor. Some brought ladders and attempted to climb them to the second floor. The militia troops guarding the prisoners had been ordered to not load their weapons. As the mob pressed against the militia, some of the militia were disarmed by the mob. A man who was reportedly either a court bailiff or a deputy sheriff seized Captain Hitch and threw him into the mob, who then removed the Captain from the courthouse. The militia troops then allowed the mob to pass them and reach the second floor. The county sheriff unlocked the door to the room where Reed and Cato were held, and pointed them out to the mob. The mob tied ropes around Reed and Cato's necks and loaded them into wagons outside the courthouse. Estimates of the size of the mob ranged from 100 to 2,500 men.[15]

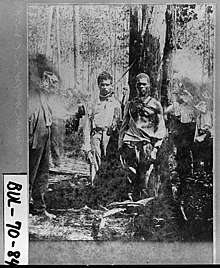

The mob carried Reed and Cato out of town, intending to lynch them at the Hodges' farm, about 6 miles (9.7 km) out of town. It was the middle of August and the day was very hot, and after traveling about 1 mile (1.6 km) the mob tired and stopped. Preparations were made to hang Reed and Cato from a tree, but the mob demanded that they be burned. Wagons returned to town to fetch kerosene and chains. While waiting for the kerosene, Paul Reed reportedly confessed to killing Henry and Claudia Hodges, and leaving the children to burn to death in the house. He said that Cato had been a lookout, and named several other men as participants in the crime. Cato was apparently unable to speak coherently. The two men were chained to a tall pine stump and doused with kerosene, ten gallons each. Wood was piled up at their feet. A photographer then recorded the scene. Cato begged to be shot or hanged, but the mob wanted him to burn, and the pyre was lit. The fire was tended until the bodies were completely consumed. Pieces of the chain and the burned stump, and even a few pieces of bone found in the ashes, were taken as souvenirs. Photos of Reed and Cato chained to the stump, of the burning bodies, and of the charred stump that remained after the fire, were also offered for sale.[16]

Consequences

Various acts of violence against African-Americans occurred in and around Statesboro after Reed and Cato were burned. A man mistaken for Handy Bell was shot multiple times. Two African-American men, father and son, were shot and killed in their home in Register, in western Bulloch County. An African-American man was shot in Portal, in northern Bulloch County, and his wife, who had just given birth three days earlier, was beaten. Many other African-Americans in the area were also beaten. The Atlanta Constitution described the events as "a carnival of crime". Many newspapers throughout the nation condemned the lynchings, comparing the mob actions unfavorably with those of "South Sea cannibals" and the "naked tribes" of "Darkest Africa." The attacks left the African-American community unsettled. Some left the county, raising concerns by cotton farmers that they would not have enough laborers available for the upcoming harvest. Several cotton-gins in the county burned, with vengeance-taking African-Americans suspected as arsonists. White farmers then worked to reduce the level of violence directed at African-Americans in Bulloch County.[17][18][19]

A public inquiry into the lynching identified several men who had participated, including two court bailiffs, but no one was indicted.[20] Captain Hitch and five of his junior officers were court-martialed for failing to prevent the lynching of Reed and Cato.[21]

Citations

- Mosely and Brogdon, pp. 104–106.

- Baker, p. 302.

- Mosely and Brogdon, pp. 105–106.

- Mosely and Brogdon, pp. 106–107.

- Mosely and Brogdon, p. 107.

- Mosely and Brogdon, pp. 107–108.

- Keith, Jeanette (June 2005). "Review: "Cry Rape": Race, Class, and the Law in the Nineteenth-Century South". Reviews in American History. 33: 191–196. doi:10.1353/rah.2005.0031. JSTOR 30032461.

- Baker, pp. 301–303.

- Wood, p. 20.

- Baker, p. 301–302.

- Mosely and Brogdon, pp. 108–109.

- Mosely and Brogdon, pp. 109–110.

- Mosely and Brogdon, pp. 110–112.

- Mosely and Brogdon, pp. 112–113.

- Mosely and Brogdon, pp. 113–114.

- Mosely and Brogdon, pp. 114–115.

- Mosely and Brogdon, pp. 116.

- Baker, p. 308.

- "The Georgia Lynching". The Literary Digest. 29 (9): 245–246. August 27, 1904 – via Google Books.

- Wood, p. 22.

- "Shortcomings of Southern Militia". Public Opinion. 37: 361. September 22, 1904 – via Google books.

Sources

- Moseley, Charlton; Brogdon, Frederick (Summer 1981). "A Lynching at Statesboro: the Story of Paul Reed and Will Cato". The Georgia Historical Quarterly. 65 (2): 104–118. JSTOR 40580763.

- Baker, Ray Stannard (January 1905). "What is a Lynching? A Study of Mob Justice, South and North". McClure's Magazine. 24 (3): 299–314 – via Google Books.

- Wood, Amy Louise (2009). Lynching and Spectacle: Witnessing Racial Violence in America, 1890-1940. The University of North Carolina Press. pp. 20–23. ISBN 978-0-8078-7811-8.

Further reading

- Moseley, Clem Charlton (2018). Foss, Jenny Starling (ed.). The Hodges Family Murders & The Lynching of Paul Reed and Will Cato. Statesboro, Georgia: Bulloch County Historical Society. ISBN 978-0-692-13735-2. Reprint of Moseley and Brogdon, with additional primary material.

Contemporary news reports

- "Negroes Shot and Flogged in Georgia" (PDF). The New York Times. August 24, 1904. Retrieved 4 February 2019.

- "Burned at Stake". 31 (323). Los Angeles Herald. Associated Press. August 17, 1904. Retrieved 25 February 2019.

Theses

- Smith, John Douglas (January 1993). Statesboro Blues (PDF) (PhD). University of Virginia. Retrieved January 13, 2020.

- Millin, Eric Tabor (2002). Defending the Sacred Hearth: Religion, Politics and Racial Violence in Georgia, 1904-1906 (PDF) (MA). Athens, Georgia: University of Georgia. Retrieved 4 February 2019.