Solenodon

Solenodons (meaning "slotted-tooth") are venomous, nocturnal, burrowing, insectivorous mammals belonging to the family Solenodontidae. The two living solenodon species are the Cuban solenodon (Solenodon cubanus), and the Hispaniolan solenodon (Solenodon paradoxus). Both species are classified as "Endangered" due to habitat destruction and predation by non-native cats, dogs and mongooses, introduced by humans to the solenodons' home islands to control snakes and rodents.[4][5][6]

| Solenodon[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| Hispaniolan solenodon | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Eulipotyphla |

| Family: | Solenodontidae Gill, 1872 |

| Genus: | Solenodon Brandt, 1833 |

| Type species | |

| Solenodon paradoxus Brandt, 1833 | |

| Species | |

|

† Solenodon arredondoi | |

The Hispaniolan solenodon covers a wide range of habitats on the island of Hispaniola from lowland dry forest to highland pine forest. Two other described species became extinct during the Quaternary.[1] Oligocene North American genera, such as Apternodus, have been suggested as relatives of Solenodon, but the origins of the animal remain obscure.[2]

Only one genus, Solenodon, is known. Other genera have been erected but are now regarded as junior synonyms. Solenodontidae shows retention of primitive mammal characteristics. In 2016, solenodons were confirmed by genetic analysis as belonging to an evolutionary branch that split from the lineage leading to hedgehogs, moles, and shrews before the Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction event.[7] They are one of two families of Caribbean soricomorphs.

The other family, Nesophontidae, became extinct during the Holocene. Molecular data suggest they diverged from solenodons roughly 57 million years ago.[8] The solenodon is estimated to have diverged from other living mammals about 73 million years ago.[8][9]

Characteristics

Traditionally, Solenodons' closest relatives were considered to be the giant water shrew of Africa and Tenrecidae of Madagascar,[10] though they are now known to be more closely related to true shrews (Eulipotyphla).[7][11] Solenodons resemble very large shrews, and are often compared to them; with extremely elongated cartilaginous snouts, long, naked, scaly tails, hairless feet, and small eyes. The Cuban solenodon is generally smaller than its Hispaniolan counterpart. It is also a rusty brown with black on its throat and back. The Hispaniolan solenodon is a darker brown with yellowish tint to the face.[12] The snout is flexible and, in the Hispaniolan solenodon, actually has a ball-and-socket joint at the base to increase its mobility. This allows the animal to investigate narrow crevices where potential prey may be hiding.

Solenodons are also noted for the glands in their inguinal and groin areas that secrete what is described as a musky, goat-like odor. Solenodons range from 28 to 32 cm (11 to 13 in) from nose to rump, and weigh between 0.7 and 1.0 kg (1.5 and 2.2 lb).[13]

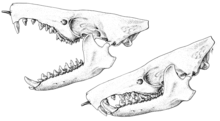

Solenodons have a few unusual traits, one of them being the position of the two teats on the female, almost on the buttocks of the animal, and another being the venomous saliva that flows from modified salivary glands in the mandible through grooves on the second lower incisors ("solenodon" derives from the Greek "grooved tooth"). Solenodons are among a handful of venomous mammals. Fossil records show that some other now-extinct mammal groups also had the dental venom delivery system, indicating that the solenodon's most distinct characteristic may have been a more general ancient mammalian characteristic that has been lost in most modern mammals and is only retained in a couple of very ancient lineages.[14] The solenodon has often been called a "living fossil" because it has endured virtually unchanged for the past 76 million years.[15]

It is not known exactly how long solenodons can live in the wild. However, certain individuals of the Cuban species have been recorded to have lived for up to five years in captivity and individuals of the Hispaniolan species for up to eleven years.

West Indian natives have long known about the venomous character of the solenodon bite. Early studies on the nature of the tiny mammal's saliva suggested that it was very similar to the neurotoxic venom of certain snakes. More recently, the venom has been found to be related to that of the northern short-tailed shrew and it is mostly composed of kallikreins KLK1, serine proteases that prevent blood clotting, cause hypotension and ultimately end up being fatal to the preys. Solenodons create venom in enlarged submaxillary glands, and only inject venom through their bottom set of teeth. The symptoms of a solenodon bite include general depression, breathing difficulty, paralysis, and convulsions; large enough doses have resulted in death in lab studies on mice.[16][17]

Their diets consist largely of insects, earthworms, and other invertebrates, but they also eat vertebrate carrion, and perhaps even some living vertebrate prey, such as small reptiles or amphibians.[13] They have also been known to feed on fruits, roots, and vegetables. Based on observation of the solenodon in captivity, they have only been known to drink while bathing. Solenodons have a relatively unspecialised, and almost complete dentition, with a dental formula of: 3.1.3.33.1.3.3.

Solenodons find food by sniffing the ground until they come upon their prey. If the prey is small enough, the solenodon will consume it immediately. After coming across the prey, the solenodon will bring the forelimbs up to either side of the prey and then move the head forward, opening the jaw and properly catching its prey. While sniffing for food, the solenodon can get through physical barriers with the help of its sharp claws.

There has been research that suggests that males and females of the two species have different eating habits. The female has a habit of scattering the food to make sure that no morsel of food is missed as it is foraging. The male was noted to use its tongue to lap up the food and using the lower jaw as a scoop. However, these specimens were studied in captivity, so these habits may not be found in the wild.[18]

Reproduction

Solenodons give birth in a nesting burrow to one or two young. The young remain with the mother for several months and initially follow the mother by hanging on to her elongated teats. Once they reach adulthood solenodons are solitary animals and rarely interact except to breed.[13]

The reproductive rate of solenodons is relatively low producing only two litters per year. Breeding can occur at any time. Males will not aid in the care for the young. The mother will nurse her offspring using her two nipples, which are placed toward the back of the animal. If the litter consists of three offspring one will become malnourished and die. The nursing period can last for up to seventy-five days.[15][19][20]

Behavior

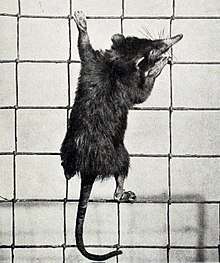

Solenodons make their homes in bushy areas in forests. During the daytime they seek refuge in caves, burrows, or hollow logs. They are easily provoked and can fly into a frenzy of squealing and biting with no warning. They run and climb quite fast, despite only ever touching the ground with toes. Solenodons are said to give off grunts similar to that of a pig or bird-call when feeling threatened. As far as predation goes, solenodons use a series of clicking noises, which create sound waves that bounce back off of objects in its path.

This form of echolocation is the main way in which a solenodon is able to navigate as well as find its food sources, because solenodons have extremely small eyes and poor vision. This well developed hearing combined with its above average sense of smell helps the solenodon survive despite its lack of visual adequacy.[21]

Status

Both extant species are endangered due to predation by the small Asian mongoose (Herpestes javanicus auropunctatus), which was introduced in colonial times to hunt snakes and rats, as well as by feral cats and dogs. The Cuban solenodon was thought to have been extinct until a live specimen was found in 2003. Marcano's solenodon (Solenodon marcanoi) became extinct after the arrival of Europeans.[22] The Hispaniolan solenodon was also once thought to be extinct, probably more because of its secretive and elusive behavior than to low population numbers. Recent studies have proven that the species is widely distributed through the island of Hispaniola, but it does not tolerate habitat degradation.

A 1981 study of the Hispaniolan solenodon in Haiti found that the species was “functionally extinct”, with the exception of a small population in the area of Massif de la Hotte. A follow-up study, in 2007, noted that the solenodon was still thriving in the area, even though the region has had an increase in human population density in recent years.[23]

Human activity has also had an adverse effect on the Solenodon population. Human development on Cuba and Hispaniola has resulted in fragmentation and habitat loss, further contributing to the reduction of the solenodon's range and numbers.[24]

The Sierra de Bahoruco, a mountain range in the south-west of the Dominican Republic that straddles the border with Haiti, was examined by conservation teams looking for solenodons. The work occurred during the day when the animals were asleep in burrows so that they could be viewed with an infrared camera. When researchers search for solenodons in daylight, they look for the following clues to their presence:

- Nearby nose-poke holes; holes that the creatures make in the ground with their long noses to probe the earth as they look for insects they can hunt and eat. After a relatively long period of time they will be covered in leaves, but a fresh hole will be covered in moist soil.

- Nearby scratches in logs that were made with their long claws.

- A strong musty goat-like smell seeping out of a burrow. The pungent odor indicates that the burrow is active and a solenodon may be present sleeping.[25]

A solenodon was captured in 2008 during a month-long expedition in the Dominican Republic, thereby allowing researchers the rare opportunity to examine it in daylight. The Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust and the Ornithological Society of Hispaniola were able to take measurements and DNA from the creature before it was released. It was the only trapping made from the entire month-long expedition. The new information gathered was significant because little information is known about its current ecology, its behavior, its population status, and its genetics, and without that knowledge it is difficult for researchers to design effective conservation.[14]

Conservation

After the arrival of Europeans to the island, the solenodon's existence has been threatened by dogs, cats, mongooses, and more dense human settlement. Snakes and birds of prey are also threats.[26] The solenodon has no known negative effects on human populations. In addition, it serves as both pest control, helping ecosystems by keeping down the population of invertebrates, and a means of spreading fruit seeds.[27]

Today, the solenodon is one of the last two surviving native insectivorous mammals found in the Caribbean, and one of the only two remaining endemic terrestrial mammal species of Hispaniola.[28]

While the survival of the solenodon is uncertain, talk of conservation has been underway through the "Last Survivors Project", which has been collaborating with the Dominican government. In 2009, a five-year plan for conservation was funded which has been put in place to conduct field research, discover the best means by which to bring about their conservation, and organize monitoring tools to ensure their long-term survival.[29][30]

One of the aims of the conservation efforts is to increase local awareness of the species, particularly in the Dominican Republic. The Ornithological Society of Hispaniola showed pictures of the solenodon to the locals in both countries, and few knew what they were due to their nocturnal nature.[25]

References

- Hutterer, R. (2005). "Order Soricomorpha". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 222–223. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- Whidden, H. P.; Asher, R. J. (2001). "The origin of the Greater Antillean insectivorans". In Woods, Charles A.; Sergile, Florence E. (eds.). Biogeography of the West Indies: Patterns and Perspectives. Boca Raton, London, New York, and Washington, D.C.: CRC Press. pp. 237–252. ISBN 0-8493-2001-1.

- Savage, RJG; Long, MR (1986). Mammal Evolution: an illustrated guide. New York: Facts on File. p. 51. ISBN 0-8160-1194-X.

- McKie, Robin (1 June 2019). "Save the polar bears, of course … but it's the solenodons we really need to worry about". The Observer. Retrieved 3 June 2019.

- Turvey, S.; Incháustegui, S. (2008). "Hispaniolan Solenodon". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2008. Retrieved 3 June 2019.

- Kennerley, R.; Turvey, S.; Young, R. (2018). "Cuban Solenodon". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018. Retrieved 3 June 2019.

- Brandt, Adam L.; Grigorev, Kirill (April 2016). "Mitogenomic sequences support a north–south subspecies subdivision within Solenodon paradoxus". Mitochondrial DNA Part A. 28 (5): 662–670. doi:10.3109/24701394.2016.1167891. PMID 27159724.

- Brace, S.; Thomas, J. A.; Dalén, L.; Burger, J.; MacPhee, R. D. E.; Barnes, I.; Turvey, S. T. (2016). "Evolutionary History of the Nesophontidae, the Last Unplaced Recent Mammal Family". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 33 (12): 3095–3103. doi:10.1093/molbev/msw186. PMID 27624716.

- Solenodon Genome Sequenced | Genetics | Sci-News.com

- Ley, Willy (December 1964). "Anyone Else for Space?". For Your Information. Galaxy Science Fiction. pp. 94–103.

- Brace, Selina; Thomas, Jessica A.; Dalén, Love; Burger, Joachim; MacPhee, Ross D.E.; Barnes, Ian; Turvey, Samuel T. (13 September 2016). "Evolutionary history of the Nesophontidae, the last unplaced Recent mammal family" (PDF). Molecular Biology and Evolution (Epub ahead of print). 33 (12): 3095–3103. doi:10.1093/molbev/msw186. PMID 27624716.

- "Solenodon". Columbia Encyclopedia (6th ed.). Retrieved 1 September 2013.

- Nicoll, Martin (1984). Macdonald, D. (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Mammals. New York: Facts on File. pp. 748–749. ISBN 0-87196-871-1.

- Morelle, Rebecca (2009-01-09). "Venomous mammal caught on camera (video)". BBC News. Retrieved 2010-05-31.

- "Solenodons: Solenodontidae - Behavior and reproduction". Animal Life Resource.

- Ligabue-Braun, Rodrigo; Verli, Hugo; Carlini, Célia Regina (2012). "Venomous mammals: A review". Toxicon. 59 (7): 680–695. doi:10.1016/j.toxicon.2012.02.012. PMID 22410495.

- Casewell NR, Petras D, Card DC, et al. (December 2019). "Solenodon genome reveals convergent evolution of venom in eulipotyphlan mammals". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 116 (51): 25745–25755. doi:10.1073/pnas.1906117116. PMC 6926037. PMID 31772017.

- Eisenberg, J. F.; Edwin, G. (1966). "The Behavior of Solenodon paradoxus in Captivity with Comments on the Behavior of other Insectivora" (PDF). Zoologica. 51 (4): 49–60. Retrieved 24 October 2012.

- Willson, Judith. "Solenodons". Animal Facts and Resources.

- "Hispaniolan Solenodon: Reproduction". Hannah Lawinger. Archived from the original on 2013-10-29. Retrieved 2013-07-31.

- "Solenodons". animal.discovery.com. Archived from the original on 2013-10-25.

- "Solenodon marcanoi". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- Turvey, S. T.; Meredith, H. M. R.; Scofield, R. P. (2008). "Continued survival of Hispaniolan solenodon Solenodon paradoxus in Haiti". Oryx. 42 (4): 611–614. doi:10.1017/S0030605308001324.

- Cohn, Jeffrey P. (February 2010). "Opening Doors to Research in Cuba". BioScience. 60 (2): 96–99. doi:10.1525/bio.2010.60.2.3.

- Morelle, Rebecca. "Solenodon hunt: On the trail of a 'living fossil'". BBC News.

- "Adaptation". Hispaniolan Solenodon.

- Theusch, Melissa. "Cuban Solenodon". Animal Diversity Web.

- "Hispaniolan Solenodon". Edge of Existence. The Zoological Society of London. Archived from the original on 2013-10-29. Retrieved 2013-10-25.

- "Solenodon". Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust.

- "Last Survivors". lastsurvivors.org. Archived from the original on 2010-06-03. Retrieved 2018-08-31.

External links

- "Scent of a solenodon: On the trail of a living fossil (video)". BBC News. 2010-05-30. Retrieved 2010-05-30.

- EDGE of Existence "(Cuban solenodon)" Saving the World's most Evolutionarily Distinct and Globally Endangered (EDGE) species

- EDGE of Existence "(Hispaniolan solenodon)" Saving the World's most Evolutionarily Distinct and Globally Endangered (EDGE) species

- BBC News 1 June 2010 The cave of bones: A story of solenodon survival

- MencariCara 13 June 2010 MencariCara.com : Origin project slenodon