Cigarette

A cigarette is a narrow cylinder containing psychoactive material, typically tobacco, that is rolled into thin paper for smoking. Most cigarettes contain a "reconstituted tobacco" product known as "sheet", which consists of "recycled [tobacco] stems, stalks, scraps, collected dust, and floor sweepings", to which are added glue, chemicals and fillers; the product is then sprayed with nicotine that was extracted from the tobacco scraps, and shaped into curls.[1] The cigarette is ignited at one end, causing it to smolder; the resulting smoke is orally inhaled via the opposite end. Most modern cigarettes are filtered, although this does not make them safer. Cigarette manufacturers have described cigarettes as a drug administration system for the delivery of nicotine in acceptable and attractive form.[2][3][4][5] Cigarettes are addictive (because of nicotine) and cause cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, heart disease, and other health problems.

The term cigarette, as commonly used, refers to a tobacco cigarette but is sometimes used to refer to other substances, such as a cannabis cigarette. A cigarette is distinguished from a cigar by its usually smaller size, use of processed leaf, and paper wrapping, which is typically white. Cigar wrappers are typically composed of tobacco leaf or paper dipped in tobacco extract.

Smoking rates have generally declined in the developed world, but continue to rise in some developing nations.[6][7][8] Cigarette smoking causes disease and harms nearly every organ of the body.[9] Nicotine is also highly addictive. About half of cigarette smokers die of tobacco-related disease[10] and lose on average 14 years of life.[11] Every year, tobacco cigarettes kill more than 8 million people worldwide; with 1.2 million of those being non-smokers dying as the result of exposure to second-hand smoke.[12] Second-hand smoke from cigarettes causes many of the same health problems as smoking, including cancer,[13][14][15][16] which has led to legislation and policy that has prohibited smoking in many workplaces and public areas. Cigarette smoke contains over 7,000 chemical compounds, including arsenic, formaldehyde, hydrogen cyanide, lead, nicotine, carbon monoxide, acrolein, and other poisonous substances.[17] Over 70 of these are carcinogenic.[18] Cigarette use by pregnant women has also been shown to cause birth defects, including low birth weight, fetal abnormalities, and premature birth.[19]

History

The earliest forms of cigarettes were similar to their predecessor, the cigar. Cigarettes appear to have had antecedents in Mexico and Central America around the 9th century in the form of reeds and smoking tubes. The Maya, and later the Aztecs, smoked tobacco and other psychoactive drugs in religious rituals and frequently depicted priests and deities smoking on pottery and temple engravings. The cigarette and the cigar were the most common methods of smoking in the Caribbean, Mexico, and Central and South America until recent times.[20]

The North American, Central American, and South American cigarette used various plant wrappers; when it was brought back to Spain, maize wrappers were introduced, and by the 17th century, fine paper. The resulting product was called papelate and is documented in Goya's paintings La Cometa, La Merienda en el Manzanares, and El juego de la pelota a pala (18th century).[21]

By 1830, the cigarette had crossed into France, where it received the name cigarette; and in 1845, the French state tobacco monopoly began manufacturing them.[21] The French word was adopted by English in the 1840s.[22] Some American reformers promoted the spelling cigaret,[23][24] but this was never widespread and is now largely abandoned.[25]

The first patented cigarette-making machine was invented by Juan Nepomuceno Adorno of Mexico in 1847.[26] However, production climbed markedly when another cigarette-making machine was developed in the 1880s by James Albert Bonsack, which vastly increased the productivity of cigarette companies, which went from making about 40,000 hand-rolled cigarettes daily to around 4 million.[27]

In the English-speaking world, the use of tobacco in cigarette form became increasingly widespread during and after the Crimean War, when British soldiers began emulating their Ottoman Turkish comrades and Russian enemies, who had begun rolling and smoking tobacco in strips of old newspaper for lack of proper cigar-rolling leaf.[21] This was helped by the development of tobaccos suitable for cigarette use, and by the development of the Egyptian cigarette export industry.

Cigarettes may have been initially used in a manner similar to pipes, cigars, and cigarillos and not inhaled; for evidence, see the Lucky Strike ad campaign asking consumers "Do You Inhale?" from the 1930s. As cigarette tobacco became milder and more acidic, inhaling may have become perceived as more agreeable. However, Moltke noticed in the 1830s (cf. Unter dem Halbmond) that Ottomans (and he himself) inhaled the Turkish tobacco and Latakia from their pipes[28] (which are both initially sun-cured, acidic leaf varieties).

The widespread smoking of cigarettes in the Western world is largely a 20th-century phenomenon. At the start of the 20th century, the per capita annual consumption in the U.S. was 54 cigarettes (with less than 0.5% of the population smoking more than 100 cigarettes per year), and consumption there peaked at 4,259 per capita in 1965. At that time, about 50% of men and 33% of women smoked (defined as smoking more than 100 cigarettes per year).[29] By 2000, consumption had fallen to 2,092 per capita, corresponding to about 30% of men and 22% of women smoking more than 100 cigarettes per year, and by 2006 per capita consumption had declined to 1,691;[30] implying that about 21% of the population smoked 100 cigarettes or more per year.

The adverse health effects of cigarettes were known by the mid-19th century when they became known as coffins nails.[31] German doctors were the first to identify the link between smoking and lung cancer, which led to the first antitobacco movement in Nazi Germany.[32][33] During World War I and World War II, cigarettes were rationed to soldiers. During the Vietnam War, cigarettes were included with C-ration meals. In 1975, the U.S. government stopped putting cigarettes in military rations. During the second half of the 20th century, the adverse health effects of tobacco smoking started to become widely known and text-only health warnings became common on cigarette packets.

The United States has not implemented graphical cigarette warning labels, which are considered a more effective method to communicate to the public the dangers of cigarette smoking.[34] Canada, Mexico, Belgium, Denmark, Sweden, Thailand, Malaysia, India, Pakistan, Australia, Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Peru,[35] Greece, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Hungary, the United Kingdom, France, Romania, Singapore, Egypt, Nepal and Turkey, however, have both textual warnings and graphic visual images displaying, among other things, the damaging effects tobacco use has on the human body.

The cigarette has evolved much since its conception; for example, the thin bands that travel transverse to the "axis of smoking" (thus forming circles along the length of the cigarette) are alternate sections of thin and thick paper to facilitate effective burning when being drawn, and retard burning when at rest. Synthetic particulate filters may remove some of the tar before it reaches the smoker.

The "holy grail" for cigarette companies has been a cancer-free cigarette. On record, the closest historical attempt was produced by scientist James Mold. Under the name project TAME, he produced the XA cigarette. However, in 1978, his project was terminated.[36][37][38]

Since 1950, the average nicotine and tar content of cigarettes has steadily fallen. Research has shown that the fall in overall nicotine content has led to smokers inhaling larger volumes per puff.[39]

Legislation

Smoking restrictions

Many governments impose restrictions on smoking tobacco, especially in public areas. The primary justification has been the negative health effects of second-hand smoke.[40] Laws vary by country and locality. Nearly all countries have laws restricting places where people can smoke in public, and over 40 countries have comprehensive smoke-free laws that prohibit smoking in virtually all public venues. Bhutan is currently the only country in the world to completely outlaw the cultivation, harvesting, production, and sale of tobacco and tobacco products under the Tobacco Control Act of Bhutan 2010. However, small allowances for personal possession are permitted as long as the possessors can prove that they have paid import duties.[41] The Pitcairn Islands had previously banned the sale of cigarettes, but it now permits sales from a government-run store. The Pacific island of Niue hopes to become the next country to prohibit the sale of tobacco.[42] Iceland is also proposing banning tobacco sales from shops, making it prescription-only and therefore dispensable only in pharmacies on doctor's orders.[43] New Zealand hopes to achieve being tobacco-free by 2025 and Finland by 2040. Singapore and the Australian state of Tasmania have proposed a 'tobacco free millennium generation initiative' by banning the sale of all tobacco products to anyone born in and after the year 2000. In March 2012, Brazil became the world's first country to ban all flavored tobacco including menthols. It also banned the majority of the estimated 600 additives used, permitting only eight. This regulation applies to domestic and imported cigarettes. Tobacco manufacturers had 18 months to remove the noncompliant cigarettes, 24 months to remove the other forms of noncompliant tobacco.[44][45] Under sharia law, the consumption of cigarettes by Muslims is prohibited.[46]

Smoking age

In the United States, the age to buy tobacco products is 21 in all states as of 2020.

Similar laws exist in many other countries. In Canada, most of the provinces require smokers to be 19 years of age to purchase cigarettes (except for Quebec and the prairie provinces, where the age is 18). However, the minimum age only concerns the purchase of tobacco, not use. Alberta, however, does have a law which prohibits the possession or use of tobacco products by all persons under 18, punishable by a $100 fine. Australia, New Zealand, Poland, and Pakistan have a nationwide ban on the selling of all tobacco products to people under the age of 18.

Since 1 October 2007, it has been illegal for retailers to sell tobacco in all forms to people under the age of 18 in three of the UK's four constituent countries (England, Wales, Northern Ireland, and Scotland) (rising from 16). It is also illegal to sell lighters, rolling papers, and all other tobacco-associated items to people under 18. It is not illegal for people under 18 to buy or smoke tobacco, just as it was not previously for people under 16; it is only illegal for the said retailer to sell the item. The age increase from 16 to 18 came into force in Northern Ireland on 1 September 2008. In the Republic of Ireland, bans on the sale of the smaller 10-packs and confectionery that resembles tobacco products (candy cigarettes) came into force on May 31, 2007, in a bid to cut underaged smoking.

Most countries in the world have a legal vending age of 18. In Macedonia, Italy, Malta, Austria, Luxembourg, and Belgium, the age for legal vending is 16. Since January 1, 2007, all cigarette machines in public places in Germany must attempt to verify a customer's age by requiring the insertion of a debit card. Turkey, which has one of the highest percentage of smokers in its population,[47] has a legal age of 18. Japan is one of the highest tobacco-consuming nations, and requires purchasers to be 20 years of age (suffrage in Japan is 20 years old).[48] Since July 2008, Japan has enforced this age limit at cigarette vending machines through use of the taspo smart card. In other countries, such as Egypt, it is legal to use and purchase tobacco products regardless of age. Germany raised the purchase age from 16 to 18 on the 1 September 2007.

Some police departments in the United States occasionally send an underaged teenager into a store where cigarettes are sold, and have the teen attempt to purchase cigarettes, with their own or no ID. If the vendor then completes the sale, the store is issued a fine.[49] Similar enforcement practices are regularly performed by Trading Standards officers in the UK, Israel, and the Republic of Ireland.[50]

Taxation

Cigarettes are taxed both to reduce use, especially among youth, and to raise revenue. Higher prices for cigarettes discourage smoking. Every 10% increase in the price of cigarettes reduces youth smoking by about 7% and overall cigarette consumption by about 4%.[52] The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that globally cigarettes be taxed at a rate of three-quarters of cigarettes sale price as a way of deterring cancer and other negative health outcomes.[53]

Cigarette sales are a significant source of tax revenue in many localities. This fact has historically been an impediment for health groups seeking to discourage cigarette smoking, since governments seek to maximize tax revenues. Furthermore, some countries have made cigarettes a state monopoly, which has the same effect on the attitude of government officials outside the health field.[54]

In the United States, states are a primary determinant of the total tax rate on cigarettes. Generally, states that rely on tobacco as a significant farm product tend to tax cigarettes at a low rate.[55] Coupled with the federal cigarette tax of $1.01 per pack, total cigarette-specific taxes range from $1.18 per pack in Missouri to $8.00 per pack in Silver Bay, New York. As part of the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act, the federal government collects user fees to fund Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulatory measures over tobacco.

Fire-safe cigarette

Cigarettes are a frequent source of deadly fires in private homes, which prompted both the European Union and the United States to require cigarettes to be fire-standard compliant.[56][57]

According to Simon Chapman, a professor of public health at the University of Sydney, reduction of burning agents in cigarettes would be a simple and effective means of dramatically reducing the ignition propensity of cigarettes.[58] Since the 1980s, prominent cigarette manufacturers such as Philip Morris and R.J. Reynolds developed fire safe cigarettes, but did not market them.[59]

The burn rate of cigarette paper is regulated through the application of different forms of microcrystalline cellulose to the paper.[60] Cigarette paper has been specially engineered by creating bands of different porosity to create "fire-safe" cigarettes. These cigarettes have a reduced idle burning speed which allows them to self-extinguish.[61] This fire-safe paper is manufactured by mechanically altering the setting of the paper slurry.[62]

New York was the first U.S. state to mandate that all cigarettes manufactured or sold within the state comply with a fire-safe standard. Canada has passed a similar nationwide mandate based on the same standard. All U.S. states are gradually passing fire-safe mandates.[63]

The European Union in 2011 banned cigarettes that do not meet a fire-safety standard. According to a study made by the European Union in 16 European countries, 11,000 fires were due to people carelessly handling cigarettes between 2005 and 2007. This caused 520 deaths with 1,600 people injured.[64]

Cigarette advertising

Many countries have restrictions on cigarette advertising, promotion, sponsorship, and marketing. For example, in the Canadian provinces of British Columbia, Saskatchewan and Alberta, the retail store display of cigarettes is completely prohibited if persons under the legal age of consumption have access to the premises.[65] In Ontario, Manitoba, Newfoundland and Labrador, and Quebec, Canada and the Australian Capital Territory the display of tobacco is prohibited for everyone, regardless of age, as of 2010. This retail display ban includes noncigarette products such as cigars and blunt wraps.[66][67]

Warning messages in packages

As a result of tight advertising and marketing prohibitions, tobacco companies look at the pack differently: they view it as a strong component in displaying brand imagery and a creating significant in-store presence at the point of purchase. Market testing shows the influence of this dimension in shifting the consumer's choice when the same product displays in an alternative package. Studies also show how companies have manipulated a variety of elements in packs designs to communicate the impression of lower in tar or milder cigarettes, whereas the components were the same.

Some countries require cigarette packs to contain warnings about health hazards. The United States was the first,[68] later followed by other countries including Canada, most of Europe, Australia,[69] Pakistan,[70] India, Hong Kong, and Singapore. In 1985, Iceland became the first country to enforce graphic warnings on cigarette packaging.[71][72] At the end of December 2010, new regulations from Ottawa increased the size of tobacco warnings to cover three-quarters of the cigarette package in Canada.[73] As of November 2010, 39 countries have adopted similar legislation.[68]

In February 2011, the Canadian government passed regulations requiring cigarette packs to contain 12 new images to cover 75% of the outside panel and eight new health messages on the inside panel with full color.[74]

As of April 2011, Australian regulations require all packs to use a bland olive green that researchers determined to be the least attractive color,[75] with 75% coverage on the front of the pack and all of the back consisting of graphic health warnings. The only feature that differentiates one brand from another is the product name in a standard color, position, font size, and style.[76] Similar policies have since been adopted in France and the United Kingdom.[77][78] In response to these regulations, Philip Morris International, Japan Tobacco Inc., British American Tobacco Plc., and Imperial Tobacco attempted to sue the Australian government. On August 15, 2012, the High Court of Australia dismissed the suit and made Australia the first country to introduce brand-free plain cigarette packaging with health warnings covering 90 and 70% of back and front packaging, respectively. This took effect on December 1, 2012.[79]

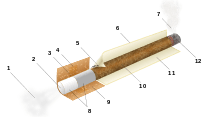

Construction

1. Mainstream smoke

2. Filtration material

3. Adhesives

4. Ventilation holes

5. Ink

6. Adhesive

7. Sidestream smoke

8. Filter

9. Tipping Paper

10. Tobacco and ingredients

11. Paper

12. Burning point and ashes

Modern commercially manufactured cigarettes are seemingly simple objects consisting mainly of a tobacco blend, paper, PVA glue to bond the outer layer of paper together, and often also a cellulose acetate–based filter.[80] While the assembly of cigarettes is straightforward, much focus is given to the creation of each of the components, in particular the tobacco blend. A key ingredient that makes cigarettes more addictive is the inclusion of reconstituted tobacco, which has additives to make nicotine more volatile as the cigarette burns.[81]

Paper

The paper for holding the tobacco blend may vary in porosity to allow ventilation of the burning ember or contain materials that control the burning rate of the cigarette and stability of the produced ash. The papers used in tipping the cigarette (forming the mouthpiece) and surrounding the filter stabilize the mouthpiece from saliva and moderate the burning of the cigarette, as well as the delivery of smoke with the presence of one or two rows of small laser-drilled air holes.[82]

Tobacco blend

The process of blending gives the end product a consistent taste from batches of tobacco grown in different areas of a country that may change in flavor profile from year to year due to different environmental conditions.[83]

Modern cigarettes produced after the 1950s, although composed mainly of shredded tobacco leaf, use a significant quantity of tobacco processing byproducts in the blend. Each cigarette's tobacco blend is made mainly from the leaves of flue-cured brightleaf, burley tobacco, and oriental tobacco. These leaves are selected, processed, and aged prior to blending and filling. The processing of brightleaf and burley tobaccos for tobacco leaf "strips" produces several byproducts such as leaf stems, tobacco dust, and tobacco leaf pieces ("small laminate").[83] To improve the economics of producing cigarettes, these byproducts are processed separately into forms where they can then be added back into the cigarette blend without an apparent or marked change in the cigarette's quality. The most common tobacco byproducts include:

- Blended leaf (BL) sheet: a thin, dry sheet cast from a paste made with tobacco dust collected from tobacco stemming, finely milled burley-leaf stem, and pectin.[84]

- Reconstituted leaf (RL) sheet: a paper-like material made from recycled tobacco fines, tobacco stems and "class tobacco", which consists of tobacco particles less than 30 mesh in size (about 0.6 mm) that are collected at any stage of tobacco processing:[85] RL is made by extracting the soluble chemicals in the tobacco byproducts, processing the leftover tobacco fibers from the extraction into a paper, and then reapplying the extracted materials in concentrated form onto the paper in a fashion similar to what is done in paper sizing. At this stage, ammonium additives are applied to make reconstituted tobacco an effective nicotine delivery system.[81]

- Expanded (ES) or improved stem (IS): ES is rolled, flattened, and shredded leaf stems that are expanded by being soaked in water and rapidly heated. Improved stem follows the same process, but is simply steamed after shredding. Both products are then dried. These products look similar in appearance, but are different in taste.[83]

In recent years, the manufacturers' pursuit of maximum profits has led to the practice of using not just the leaves, but also recycled tobacco offal[81] and the plant stem.[86] The stem is first crushed and cut to resemble the leaf before being merged or blended into the cut leaf.[87] According to data from the World Health Organization,[88] the amount of tobacco per 1000 cigarettes fell from 2.28 pounds in 1960 to 0.91 pounds in 1999, largely as a result of reconstituting tobacco, fluffing, and additives.

A recipe-specified combination of brightleaf, burley-leaf, and oriental-leaf tobacco is mixed with various additives to improve its flavors.

Additives

Various additives are combined into the shredded tobacco product mixtures, with humectants such as propylene glycol or glycerol, as well as flavoring products and enhancers such as cocoa solids, licorice, tobacco extracts, and various sugars, which are known collectively as "casings". The leaf tobacco is then shredded, along with a specified amount of small laminate, expanded tobacco, BL, RL, ES, and IS. A perfume-like flavor/fragrance, called the "topping" or "toppings", which is most often formulated by flavor companies, is then blended into the tobacco mixture to improve the consistency in flavor and taste of the cigarettes associated with a certain brand name.[83] Additionally, they replace lost flavors due to the repeated wetting and drying used in processing the tobacco. Finally, the tobacco mixture is filled into cigarette tubes and packaged.

A list of 599 cigarette additives, created by five major American cigarette companies, was approved by the Department of Health and Human Services in April 1994. None of these additives is listed as an ingredient on the cigarette pack(s). Chemicals are added for organoleptic purposes and many boost the addictive properties of cigarettes, especially when burned.

One of the classes of chemicals on the list, ammonia salts, convert bound nicotine molecules in tobacco smoke into free nicotine molecules. This process, known as freebasing, could potentially increase the effect of nicotine on the smoker, but experimental data suggests that absorption is, in practice, unaffected.[89]

Cigarette tube

Cigarette tubes are prerolled cigarette paper usually with an acetate or paper filter at the end. They have an appearance similar to a finished cigarette, but are without any tobacco or smoking material inside. The length varies from what is known as King Size (84 mm) to 100s (100 mm).[90]

Filling a cigarette tube is usually done with a cigarette injector (also known as a shooter). Cone-shaped cigarette tubes, known as cones, can be filled using a packing stick or straw because of their shape. Cone smoking is popular because as the cigarette burns, it tends to get stronger and stronger. A cone allows more tobacco to be burned at the beginning than the end, allowing for an even flavor[91]

The United States Tobacco Taxation Bureau defines a cigarette tube as "Cigarette paper made into a hollow cylinder for use in making cigarettes."[92]

Cigarette filter

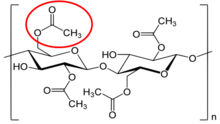

A cigarette filter or filter tip is a component of a cigarette. Filters are typically made from cellulose acetate fibre. Most factory-made cigarettes are equipped with a filter; those who roll their own can buy them separately. Filters can reduce some substances from smoke but do not make cigarettes any safer to smoke.

Cigarette butt

The common name for the remains of a cigarette after smoking is a cigarette butt. The butt is typically about 30% of the cigarette's original length. It consists of a tissue tube which holds a filter and some remains of tobacco mixed with ash. They are the most numerically frequent litter in the world.[93] Cigarette butts accumulate outside buildings, on parking lots, and streets where they can be transported through storm drains to streams, rivers, and beaches.[94] It is also called a fag-end or dog-end.[95]

In a 2013 trial the city of Vancouver, British Columbia, partnered with TerraCycle to create a system for recycling of cigarette butts. A reward of 1¢ per collected butt was offered to determine the effectiveness of a deposit system similar to that of beverage containers.[96][97]

Environmental impact

Cigarette filters are made up of thousands of polymer chains of cellulose acetate, which has the chemical structure shown to the right. Once discarded into the environment, the filters create a large waste problem. Cigarette filters are the most common form of litter in the world, as approximately 5.6 trillion cigarettes are smoked every year worldwide.[98] Of those, an estimated 4.5 trillion cigarette filters become litter every year.[99] To develop an idea of the waste weight amount produced a year the table below was created.

| Number of filters | weight |

|---|---|

| 1 pack (20) | 3.4 grams (0.12 oz) |

| sold daily (15 billion) | 2,551,000 kilograms (5,625,000 lb) |

| sold yearly (5.6 trillion) | 950,000,000 kilograms (2,100,000,000 lb) |

| estimated trash (4.5 trillion) | 765,400,000 kilograms (1,687,500,000 lb) |

Discarded cigarette filters usually end up in the water system through drainage ditches and are transported by rivers and other waterways to the ocean.

Aquatic life health concerns

In the 2006 International Coastal Cleanup, cigarettes and cigarette butts constituted 24.7% of the total collected pieces of garbage, over twice as many as any other category, which is not surprising seeing the numbers in the table above of waste produced each year.[100] Cigarette filters contain the chemicals filtered from cigarettes and can leach into waterways and water supplies.[101] The toxicity of used cigarette filters depends on the specific tobacco blend and additives used by the cigarette companies. After a cigarette is smoked, the filter retains some of the chemicals, and some of which are considered carcinogenic.[93] When studying the environmental impact of cigarette filters, the various chemicals that can be found in cigarette filters are not studied individually, due to its complexity. Researchers instead focus on the whole cigarette filter and its LD50. LD50 is defined as the lethal dose that kills 50% of a sample population. This allows for a simpler study of the toxicity of cigarettes filters. One recent study has looked at the toxicity of smoked cigarette filters (smoked filter + tobacco), smoked cigarette filters (no tobacco), and unsmoked cigarette filters (no tobacco). The results of the study showed that for the LD50of both marine topsmelt (Atherinops affinis) and freshwater fathead minnow (Pimephales promelas), smoked cigarette filters + tobacco are more toxic than smoked cigarette filters, but both are severely more toxic than unsmoked cigarette filters.[102]

| Cigarette type | Marine topsmelt | Fathead minnow |

|---|---|---|

| Smoked cigarette filter (smoked filter + tobacco) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Smoked cigarette filters (no tobacco) | 1.8 | 4.3 |

| Unsmoked cigarette filters (no tobacco) | 5.1 | 13.5 |

Other health concerns

Toxic chemicals are not the only human health concern to take into considerations; the others are cellulose acetate and carbon particles that are breathed in while smoking. These particles are suspected of causing lung damage.[103] The next health concern is that of plants. Under certain growing conditions, plants on average grow taller and have longer roots than those exposed to cigarette filters in the soil. A connection exists between cigarette filters introduced to soil and the depletion of some soil nutrients over a period time. Another health concern to the environment is not only the toxic carcinogens that are harmful to the wildlife, but also the filters themselves pose an ingestion risk to wildlife that may presume filter litter as food.[104] The last major health concern to make note of for marine life is the toxicity that deep marine topsmelt and fathead minnow pose to their predators. This could lead to toxin build-up (bioaccumulation) in the food chain and have long reaching negative effects. Smoldering cigarette filters have also been blamed for triggering fires from residential areas[105] to major wildfires and bushfires which has caused major property damage and also death[106][107][108] as well as disruption to services by triggering alarms and warning systems.[109]

Degradation

Once in the environment, cellulose acetate can go through biodegradation and photodegradation.[110][111][112] Several factors go into determining the rate of both degradation process. This variance in rate and resistance to biodegradation in many conditions is a factor in littering[113] and environmental damage.[114]

Biodegradation

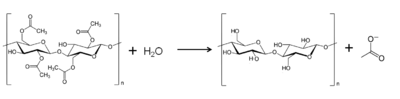

The first step in the biodegradation of cellulose acetate is the deactylation of the acetate from the polymer chain (which is the opposite of acetylation). An acetate is a negative ion with the chemical formula of C2H3O2−. Deacetylation can be performed by either chemical hydrolysis or acetylesterase. Chemical hydrolysis is the cleavage of a chemical bond by addition of water. In the reaction, water (H2O) reacts with the acetic ester functional group attached the cellulose polymer chain and forms an alcohol and acetate. The alcohol is simply the cellulose polymer chain with the acetate replaced with an alcohol group. The second reaction is exactly the same as chemical hydrolysis with the exception of the use of an acetylesterase enzyme. The enzyme, found in most plants, catalyzes the chemical reaction shown below.[115]

- acetic ester + H2O ⇌ alcohol + acetate

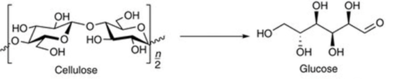

In the case of the enzymatic reaction, the two substrates (reactants) are again acetic ester and H2O, the two products of the reaction are alcohol and acetate. This reaction is exactly the same as the chemical hydrolysis. Both of these products are perfectly fine in the environment. Once the acetate group is removed from the cellulose chain, the polymer can be readily degraded by cellulase, which is another enzyme found in fungi, bacteria, and protozoans. Cellulases break down the cellulose molecule into monosaccharides ("simple sugars") such as beta-glucose, or shorter polysaccharides and oligosaccharides.

These simple sugars are not harmful to the environment and are in fact are a useful product for many plants and animals. The breakdown of cellulose is of interest in the field of biofuel.[116] Due to the conditions that affect the process, large variation in the degradation time of cellulose acetate occurs.

Factors in biodegradation

The duration of the biodegradation process is cited as taking as little as one month[110] to as long as 15 years or more, depending on the environmental conditions. The major factor that affects the biodegradation duration is the availability of acetylesterase and cellulase enzymes. Without these enzymes, biodegradation only occurs through chemical hydrolysis and stops there. Temperature is another major factor, if the organisms that contain the enzymes are too cold to grow, then biodegradation is severely hindered. Availability of oxygen in the environment also affects the degradation. Cellulose acetate is degraded within 2–3 weeks under aerobic assay systems of in vitro enrichment cultivation techniques and an activated sludge wastewater treatment system.[117] It is degraded within 14 weeks under anaerobic conditions of incubation with special cultures of fungi.[118] Ideal conditions were used for the degradation (i.e. right temperature, and available organisms to provide the enzymes). Thus, filters last longer in places with low oxygen concentration (ex. swamps and bogs). Overall, the biodegraditon process of cellulose acetate is not an instantaneous process.

Photodegradation

The other process of degradation is photodegradation, which is when a molecular bond is broken by the absorption of photon radiation (i.e. light). Due to cellulose acetate carbonyl groups, the molecule naturally absorbs light at 260 nm,[119] but it contains some impurities which can absorb light. These impurities are known to absorb light in the far UV light region (< 280 nm).[120] The atmosphere filters radiation from the sun and allows radiation of > 300 nm only to reach the surface. Thus, the primary photodegradation of cellulose acetate is considered insignificant to the total degradation process, since cellulose acetate and its impurities absorb light at shorter wavelengths. Research is focused on the secondary mechanisms of photodegradation of cellulose acetate to help make up for some of the limitations of biodegradation. The secondary mechanisms would be the addition of a compound to the filters that would be able to absorb natural light and use it to start the degradation process. The main two areas of research are in photocatalytic oxidation[121] and photosensitized degradation.[122] Photocatalytic oxidation uses a species that absorbs radiation and creates hydroxyl radicals that react with the filters and start the breakdown. Photosensitized degradation, though, uses a species that absorbs radiation and transfers the energy to the cellulose acetate to start the degradation process. Both processes use other species that absorbed light > 300 nm to start the degradation of cellulose acetate.

Solution and remediation projects

Several options are available to help reduce the environmental impact of cigarette butts. Proper disposal into receptacles leads to decreased numbers found in the environment and their effect on the environment. Another method is making fines and penalties for littering filters; many governments have sanctioned stiff penalties for littering of cigarette filters; for example, Washington imposes a penalty of $1,025 for littering cigarette filters.[123] Another option is developing better biodegradable filters; much of this work relies heavily on the research in the secondary mechanism for photodegradation as stated above, but a new research group has developed an acid tablet that goes inside the filters, and once wet enough, releases acid that speeds up the degradation to around two weeks.[124] The research is still only in test phase and the hope is soon it will go into production. The next option is using cigarette packs with a compartment in which to discard cigarette butts, implementing monetary deposits on filters, increasing the availability of butt receptacles, and expanding public education. It may even be possible to ban the sale of filtered cigarettes altogether on the basis of their adverse environmental impact.[125] Recent research has been put into finding ways to use the filter waste to develop a desired product. One research group in South Korea has developed a simple one-step process that converts the cellulose acetate in discarded cigarette filters into a high-performing material that could be integrated into computers, handheld devices, electrical vehicles, and wind turbines to store energy. These materials have demonstrated superior performance as compared to commercially available carbon, grapheme, and carbon nanotubes. The product is showing high promise as a green alternative for the waste problem.[126]

Consumption

Smoking has become less popular, but is still a large public health problem globally. Worldwide, smoking rates fell from 41% in 1980 to 31% in 2012, although the actual number of smokers increased because of population growth.[128] In 2017, 5.4 trillion cigarettes were produced globally, and were smoked by almost 1 billion people.[129] Smoking rates have leveled off or declined in most countries but is increasing in some low- and middle-income countries. The significant reductions in smoking rates in the United States, United Kingdom, Australia, Brazil, and other countries that implemented strong tobacco control programs have been offset by the increasing consumption in low income countries, especially China. The Chinese market now consumes more cigarettes than all other low- and middle-income countries combined.

Other regions are increasingly playing larger roles in the growing global smoking epidemic. The WHO Eastern Mediterranean Region (EMRO) now has the highest growth rate in the cigarette market, with more than a one-third increase in cigarette consumption since 2000. Due to its recent dynamic economic development and continued population growth, Africa presents the greatest risk in terms of future growth in tobacco use.

Within countries, patterns of cigarette consumption also can vary widely. For example, in many of the countries where few women smoke, smoking rates are often high in males (e.g., in Asia). By contrast, in most developed countries, female smoking rates are typically only a few percentage points below those of males. In many high and middle income countries lower socioeconomic status is a strong predictor of smoking.

Smoking rates in the United States have dropped by more than half from 1965 to 2016, falling from 42% to 15.5% of US adults.[130] Australia is cutting their overall smoking consumption faster than most of the developed world, in part due to landmark Plain Packaging Act, which standardized the appearance of cigarette packs. Other countries have considered similar measures. In New Zealand, a bill has been presented to parliament in which the government's associate health minister said "takes away the last means of promoting tobacco as a desirable product."[131]

| Percent smoking | ||

|---|---|---|

| Region | Men | Women |

| Africa | 18% | 2% |

| Americas | 21% | 12% |

| Eastern Mediterranean | 34% | 2% |

| Europe | 38% | 21% |

| Southeast Asia | 32% | 2% |

| Western Pacific | 46% | 3% |

| Country | Population (millions) | Cigarettes consumed (billions) | Cigarettes consumed (per capita) |

|---|---|---|---|

| China | 1,386 | 2,351 | 2,043 |

| Indonesia | 264 | 316 | 1,675 |

| Russia | 145 | 278 | 2,295 |

| United States | 327 | 266 | 1,017 |

| Japan | 127 | 174 | 1,583 |

Lights

Some cigarettes are marketed as “Lights”, “Milds”, or “Low-tar.”[134] These cigarettes were historically marketed as being less harmful, but there is no research showing that they are any less harmful. The filter design is one of the main differences between light and regular cigarettes, although not all cigarettes contain perforated holes in the filter. In some light cigarettes, the filter is perforated with small holes that theoretically diffuse the tobacco smoke with clean air. In regular cigarettes, the filter does not include these perforations. In ultralight cigarettes, the filter's perforations are larger. The majority of major cigarette manufacturers offer a light, low-tar, and/or mild cigarette brand. Due to recent U.S. legislation prohibiting the use of these descriptors, tobacco manufacturers are turning to color-coding to allow consumers to differentiate between regular and light brands.[135]

Research shows that smoking "light" or "low-tar" cigarettes is just as harmful as smoking other cigarettes.[136][137][138]

Notable cigarette brands

- 520

- 555

- Ashford

- Amber Leaf

- Army Club

- Ardath

- Basic

- Bel Air

- Benson & Hedges

- Berkeley

- Camel

- Capri

- Chesterfield

- Davidoff

- Dunhill

- Djarum

- Doral

- du Maurier

- Eclipse

- Embassy

- Eve

- Export A

- Fatima

- Fortuna

- Gauloises

- Gitanes

- Gold Flake

- Golden Virginia

- Gold Leaf

- Kyriazi Freres

- Kent

- Kool

- Lambert and Butler

- L&M

- Lark

- Lucky Strike

- Marlboro

- Max

- Mayfair

- Merit

- Mild Seven

- More

- Nat Sherman

- Natural American Spirit

- Newport

- Next

- Nil

- Old Gold

- Pall Mall

- Parliament

- Perilly's

- Peter Stuyvesant

- Peter Jackson

- Philip Morris

- Pyramid

- Player's

- Prince

- Raleigh

- Ronhill

- Salem

- Sampoerna

- Seneca

- Senior Service

- Smokin Joes

- Sobranie

- Sovereign

- Sterling

- Surya

- Tareyton

- Vantage

- Viceroy

- Virginia Slims

- West

- Woodbine

- Windsor Blue

- Winfield

- Winston

Gateway theory

A very strong argument can be made about the association between adolescent exposure to nicotine by smoking conventional cigarettes and the subsequent onset of using other dependence-producing substances.[139] Strong, temporal, and dose-dependent associations have been reported, and a plausible biological mechanism (via rodent and human modeling) suggests that long-term changes in the neural reward system take place as a result of adolescent smoking.[139] Adolescent smokers of conventional cigarettes have disproportionately high rates of comorbid substance abuse, and longitudinal studies have suggested that early adolescent smoking may be a starting point or "gateway" for substance abuse later in life, with this effect more likely for persons with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).[139] Although factors such as genetic comorbidity, innate propensity for risk taking, and social influences may underlie these findings, both human neuroimaging and animal studies suggest a neurobiological mechanism also plays a role.[139] In addition, behavioral studies in adolescent and young adult smokers have revealed an increased propensity for risk taking, both generally and in the presence of peers, and neuroimaging studies have shown altered frontal neural activation during a risk-taking task as compared with nonsmokers.[139] In 2011, Rubinstein and colleagues used neuroimaging to show decreased brain response to a natural reinforcer (pleasurable food cues) in adolescent light smokers (1–5 cigarettes per day), with their results highlighting the possibility of neural alterations consistent with nicotine dependence and altered brain response to reward even in adolescent low-level smokers.[139]

Health effects

Smokers

The harm from smoking comes from the many toxic chemicals in the natural tobacco leaf and those formed in smoke from burning tobacco. People keep smoking because the nicotine, the primary psychoactive chemical in cigarettes, is highly addictive.[140] About half of smokers die from a smoking-related cause. Smoking harms nearly every organ of the body. Smoking leads most commonly to diseases affecting the heart, liver, and lungs, being a major risk factor for heart attacks, strokes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (including emphysema and chronic bronchitis), and cancer (particularly lung cancer, cancers of the larynx and mouth, and pancreatic cancer). It also causes peripheral vascular disease and hypertension. Children born to women who smoke during pregnancy are at higher risk of congenital disorders, cancer, respiratory disease, and sudden death. On average, each cigarette smoked is estimated to shorten life by 11 minutes.[11][141][142] Starting smoking earlier in life and smoking cigarettes higher in tar increases the risk of these diseases. The World Health Organization estimates that tobacco kills 8 million people each year as of 2019[143] and 100 million deaths over the course of the 20th century.[144] Cigarettes produce an aerosol containing over 4,000 chemical compounds, including nicotine, carbon monoxide, acrolein, and oxidant substances.[17] Over 70 of these are carcinogens.[18]

The most important chemical compounds causing cancer are those that produce DNA damage since such damage appears to be the primary underlying cause of cancer.[145] Cunningham et al.[146] combined the microgram weight of the compound in the smoke of one cigarette with the known genotoxic effect per microgram to identify the most carcinogenic compounds in cigarette smoke. The seven most important carcinogens in tobacco smoke are shown in the table, along with DNA alterations they cause.

| Compound | Micrograms per cigarette | Effect on DNA | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acrolein | 122.4 | Reacts with deoxyguanine and forms DNA crosslinks, DNA-protein crosslinks and DNA adducts | [147] |

| Formaldehyde | 60.5 | DNA-protein crosslinks causing chromosome deletions and re-arrangements | [148] |

| Acrylonitrile | 29.3 | Oxidative stress causing increased 8-oxo-2'-deoxyguanosine | [149] |

| 1,3-butadiene | 105.0 | Global loss of DNA methylation (an epigenetic effect) as well as DNA adducts | [150] |

| Acetaldehyde | 1448.0 | Reacts with deoxyguanine to form DNA adducts | [151] |

| Ethylene oxide | 7.0 | Hydroxyethyl DNA adducts with adenine and guanine | [152] |

| Isoprene | 952.0 | Single and double strand breaks in DNA | [153] |

"Ulcerative colitis is a condition of nonsmokers in which nicotine is of therapeutic benefit."[154] A recent review of the available scientific literature concluded that the apparent decrease in Alzheimer disease risk may be simply because smokers tend to die before reaching the age at which it normally occurs. "Differential mortality is always likely to be a problem where there is a need to investigate the effects of smoking in a disorder with very low incidence rates before age 75 years, which is the case of Alzheimer's disease", it stated, noting that smokers are only half as likely as nonsmokers to survive to the age of 80.[155]

Second-hand smoke

Second-hand smoke is a mixture of smoke from the burning end of a cigarette and the smoke exhaled from the lungs of smokers. It is involuntarily inhaled, lingers in the air for hours after cigarettes have been extinguished, and can cause a wide range of adverse health effects, including cancer, respiratory infections, and asthma.[156] Nonsmokers who are exposed to second-hand smoke at home or work increase their heart disease risk by 25–30% and their lung cancer risk by 20–30%. Second-hand smoke has been estimated to cause 38,000 deaths per year, of which 3,400 are deaths from lung cancer in nonsmokers.[157] Sudden infant death syndrome, ear infections, respiratory infections, and asthma attacks can occur in children who are exposed to second-hand smoke.[158][159][160] Scientific evidence shows that no level of exposure to second-hand smoke is safe.[158][159]

Smoking cessation

Smoking cessation (quitting smoking) is the process of discontinuing the practice of inhaling a smoked substance.[161]

Smoking cessation can be achieved with or without assistance from healthcare professionals or the use of medications.[162] Methods that have been found to be effective include interventions directed at or through health care providers and health care systems; medications including nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) and varenicline; individual and group counselling; and web-based or stand-alone computer programs. Although stopping smoking can cause short-term side effects such as reversible weight gain, smoking cessation services and activities are cost-effective because of the positive health benefits.

At the University of Buffalo, researchers found out that fruit and vegetable consumption can help a smoker cut down or even quit smoking[163]

- A growing number of countries have more ex-smokers than smokers.[164]

- Early "failure" is a normal part of trying to stop, and more than one attempt at stopping smoking prior to longer-term success is common.[162]

- NRT, other prescribed pharmaceuticals, and professional counselling or support also help many smokers.[162]

- However, up to three-quarters of ex-smokers report having quit without assistance ("cold turkey" or cut down then quit), and cessation without professional support or medication may be the most common method used by ex-smokers.[162]

Tobacco contains nicotine. Smoking cigarettes can lead to nicotine addiction.[165]:2300–2301 The addiction begins when nicotine acts on nicotinic acetylcholine receptors to release neurotransmitters such as dopamine, glutamate, and gamma-aminobutyric acid.[165]:2296 Cessation of smoking leads to symptoms of nicotine withdrawal such as anxiety and irritability.[165]:2298 Professional smoking cessation support methods generally endeavour to address both nicotine addiction and nicotine withdrawal symptoms.

The number of nicotinic receptors in the brain returns to the level of a nonsmoker between 6 and 12 weeks after quitting.[166] In 2019, the FDA authorized the selling of low-nicotine cigarettes in hopes of lowering the number of people addicted to nicotine.[167]

Electronic cigarette

An electronic cigarette is a handheld battery-powered vaporizer that simulates smoking by providing some of the behavioral aspects of smoking, including the hand-to-mouth action of smoking, but without combusting tobacco.[168] Using an e-cigarette is known as "vaping" and the user is referred to as a "vaper."[169] Instead of cigarette smoke, the user inhales an aerosol, commonly called vapor.[170] E-cigarettes typically have a heating element that atomizes a liquid solution called e-liquid.[171] E-cigarettes are automatically activated by taking a puff;[172] others turn on manually by pressing a button.[169] Some e-cigarettes look like traditional cigarettes,[173] but they come in many variations.[169] Most versions are reusable, though some are disposable.[174] There are first-generation,[175] second-generation,[176] third-generation,[177] and fourth-generation devices.[178] E-liquids usually contain propylene glycol, glycerin, nicotine, flavorings, additives, and differing amounts of contaminants.[179] E-liquids are also sold without propylene glycol,[180] nicotine,[181] or flavors.[182]

The benefits and the health risks of e-cigarettes are uncertain.[183][184][185] There is tentative evidence they may help people quit smoking,[186] although they have not been proven to be more effective than smoking cessation medicine.[187] There is concern with the possibility that non-smokers and children may start nicotine use with e-cigarettes at a rate higher than anticipated than if they were never created.[188] Following the possibility of nicotine addiction from e-cigarette use, there is concern children may start smoking cigarettes.[188] Youth who use e-cigarettes are more likely to go on to smoke cigarettes.[189][190] Their part in tobacco harm reduction is unclear,[191] while another review found they appear to have the potential to lower tobacco-related death and disease.[192] Regulated US Food and Drug Administration nicotine replacement products may be safer than e-cigarettes,[191] but e-cigarettes are generally seen as safer than combusted tobacco products.[193][194] It is estimated their safety risk to users is similar to that of smokeless tobacco.[195] The long-term effects of e-cigarette use are unknown.[196][197][198] The risk from serious adverse events was reported in 2016 to be low.[199] Less serious adverse effects include abdominal pain, headache, blurry vision,[200] throat and mouth irritation, vomiting, nausea, and coughing.[201] Nicotine itself is associated with some health harms.[202] In 2019 and 2020, an outbreak of severe lung illness throughout the US was linked to the use of vaping products[203]

E-cigarettes create vapor made of fine and ultrafine particles of particulate matter,[201] which have been found to contain propylene glycol, glycerin, nicotine, flavors, small amounts of toxicants,[201] carcinogens,[204] and heavy metals, as well as metal nanoparticles, and other substances.[201] Its exact composition varies across and within manufacturers, and depends on the contents of the liquid, the physical and electrical design of the device, and user behavior, among other factors.[170] E-cigarette vapor potentially contains harmful chemicals not found in tobacco smoke.[205] E-cigarette vapor contains fewer toxic chemicals,[201] and lower concentrations of potential toxic chemicals than cigarette smoke.[206] The vapor is probably much less harmful to users and bystanders than cigarette smoke,[204] although concern exists that the exhaled vapor may be inhaled by non-users, particularly indoors.[207]

See also

Bibliography

- Wilder, Natalie; Daley, Claire; Sugarman, Jane; Partridge, James (April 2016). "Nicotine without smoke: Tobacco harm reduction". UK: Royal College of Physicians. pp. 1–191.

- "E-Cigarette Use Among Youth and Young Adults: A Report of the Surgeon General" (PDF). United States Department of Health and Human Services. Surgeon General of the United States. 2016. pp. 1–298.

- "Electronic nicotine delivery systems" (PDF). World Health Organization. 21 July 2014. pp. 1–13.

References

- Rabinoff, Michael; Caskey, Nicholas; Rissling, Anthony; Park, Candice (November 2007). "Pharmacological and Chemical Effects of Cigarette Additives". American Journal of Public Health. 97 (11): 1981–1991. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2005.078014. PMC 2040350. PMID 17666709.

- Hurt, RD; Robertson, CR (7 October 1998). "Prying open the door to the tobacco industry's secrets about nicotine: the Minnesota Tobacco Trial". JAMA. 280 (13): 1173–81. doi:10.1001/jama.280.13.1173. PMID 9777818.

- Cummings, KM (September 2015). "Is it not time to reveal the secret sauce of nicotine addiction?". Tobacco Control. 24 (5): 420–1. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2015-052631. PMID 26293383.

- Teague, CE (1972). Research planning memorandum on the nature of the tobacco business and the crucial role of the nicotine therein. Bates: 500915683–500915691: R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Dunn, W (1977). Smoker psychology program review. Bates: 1000046538–1000046546: Philip Morris Tobacco Company.CS1 maint: location (link)

- "Cigarette Smoking Among Adults - United States, 2006". Cdc.gov. Retrieved 2009-11-13.

- "WHO/WPRO-Smoking Statistics". Wpro.who.int. 2002-05-28. Archived from the original on November 8, 2009. Retrieved 2009-11-13.

- "Home". The Tobacco Atlas.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018, March 5). 2014 SGR: The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress. Retrieved November 25, 2019, from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website: https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/sgr/50th-anniversary/index.htm

- Doll, R.; Peto, R.; Boreham, J.; Sutherland, I. (2004). "Mortality in relation to smoking: 50 years' observations on male British doctors". BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 328 (7455): 1519. doi:10.1136/bmj.38142.554479.AE. PMC 437139. PMID 15213107.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-12-29. Retrieved 2009-11-13.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- World Health Organization. (2019, July 26). Tobacco. Retrieved November 25, 2019, from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tobacco

- "WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control" (PDF). World Health Organization. 2005-02-27. Retrieved 2009-01-12.

Parties recognize that scientific evidence has unequivocally established that exposure to tobacco has the potential to cause death, disease and disability

- "The Health Consequences of Involuntary Exposure to Tobacco Smoke: A Report of the Surgeon General". Surgeon General of the United States. 2006-06-27. Retrieved 2014-06-16.

Secondhand smoke exposure causes disease and premature death in children and adults who do not smoke

- Board, California Environmental Protection Agency: Air Resources (2005-06-24). "Proposed Identification of Environmental Tobacco Smoke as a Toxic Air Contaminant". California Environmental Protection Agency. Retrieved 2009-01-12. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Tobacco Smoke and Involuntary Smoking (PDF). International Agency for Research on Cancer. 2004. ISBN 9789283215837. Retrieved 2009-01-12.

There is sufficient evidence that involuntary smoking (exposure to secondhand or 'environmental' tobacco smoke) has the potential to cause lung cancer in humans

- Csordas, Adam; Bernhard, David (2013). "The biology behind the atherothrombotic effects of cigarette smoke". Nature Reviews Cardiology. 10 (4): 219–230. doi:10.1038/nrcardio.2013.8. ISSN 1759-5002. PMID 23380975.

- "Tobacco Smoking" (PDF). Personal Habits and Indoor Combustions. 100E. International Agency for Research on Cancer. 2012. p. 44.

- "Smoking While Pregnant Causes Finger, Toe Deformities". Science Daily. Retrieved March 6, 2007.

- Robicsek, Francis Smoke; Ritual Smoking in Central America pp. 30–37

- Goodman, Jordan Elliot (1993). Tobacco in history: the cultures of dependence. New York: Routledge. p. 97. ISBN 978-0-415-04963-4.

- Oxford English Dictionary, s.v.

- Circulars of Information of the Bureau of Education, The Spelling Reform, No. 7-1880, 1881, p. 25

- Henry Gallup Paine, Simplified Spelling Board, Handbook of Simplified Spelling, New York, 1920, p. 6

- Google Books Ngram Viewer for cigaret vs. cigarette in US and British corpora

- Office, Patent (29 December 1870). "Patents for inventions. Abridgments of specifications" – via Google Books.

- James, Randy (2009-06-15). "A Brief History Of Cigarette Advertising". TIME. Retrieved 2012-03-25.

- "Projekt Gutenberg-DE - SPIEGEL ONLINE - Nachrichten - Kultur". Gutenberg.spiegel.de. Retrieved 2012-03-25.

- "Tobacco Use, United States 1990-1999". Oncology (Williston Park). 13 (12). December 1999.

- Tobacco Outlook Report, Economic Research Service, U.S. Dept. of Agriculture

- "Definition of COFFIN NAIL".

- Roffo, A. H. (January 8, 1940). "Krebserzeugende Tabakwirkung [Carcingogenic effects of tobacco"] (in German). Berlin: J. F. Lehmanns Verlag. Retrieved 2009-09-13.

- Proctor, R. N. (2006). "Angel H Roffo: The forgotten father of experimental tobacco carcinogenesis". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 84 (6): 494–496. doi:10.2471/BLT.06.031682. PMC 2627373. PMID 16799735.

- Hammond D, Fong GT, McNeill A, Borland R, Cummings KM (June 2006). "Effectiveness of cigarette warning labels in informing smokers about the risks of smoking: findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey". Tob Control. 15 Suppl 3 (Suppl 3): iii19–25. doi:10.1136/tc.2005.012294. PMC 2593056. PMID 16754942.

- ccpa.unc.edu

- Storr, Will (2012-09-06). "Quest for a safer cigarette". The Daily Telegraph. London.

- "Project XA".

- "Safer cigarette history".

- Hoffmann, D; Hoffmann, D (March 1997). "The changing cigarette, 1950-1995". Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health. 50 (4): 307–364. doi:10.1080/009841097160393. PMID 9120872.

- WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control; First international treaty on public health, adopted by 192 countries and signed by 168. Its Article 8.1 states, "Parties recognize that scientific evidence has unequivocally established that exposure to tobacco causes death, disease and disability."

- Gayatri Parameswaran. "Bhutan smokers huff and puff over tobacco ban - Features". Al Jazeera English. Retrieved 2013-01-02.

- Marks, Kathy (2008-07-09). "World's smallest state aims to become the first smoke-free paradise island - Australasia - World". The Independent. London. Retrieved 2013-01-02.

- Helen Pidd (2011-07-04). "What a drag … Iceland considers prescription-only cigarettes | World news". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 2013-01-02.

- "WHO | Brazil - Flavoured cigarettes banned". Who.int. 2012-03-13. Retrieved 2013-01-02.

- "Eyes on Trade: Brazil's flavored cigarette ban now targeted". Citizen.typepad.com. 2012-04-16. Retrieved 2013-01-02.

- Dubai: The Complete Residents' Guide - Page 27, 2006

- "Total adult smokers by country". NationMaster.com. Retrieved 2008-06-04.

- "CIA - The World Factbook - Japan". Cia.gov. Retrieved 2012-03-25.

- Archived March 26, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- "UK | England | Bristol/Somerset | Retailers sell tobacco to youths". BBC News. 2005-09-01. Retrieved 2012-03-25.

- Ritchie, Hannah; Roser, Max (23 May 2013). "Smoking". Our World in Data. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- "Higher Cigarette Taxes". Tobaccofreekids.org. Retrieved 2009-11-13.

- "Closing in on cancer". The Economist. Retrieved 2017-09-25.

- "U.S. Aided Cigarette Firms in Conquests Across Asia". Washingtonpost.com. 1996-11-17. Retrieved 2009-11-13.

- "State Excise Tax Rates On Cigarettes (January 1, 2007)". Taxadmin.org. Archived from the original on November 9, 2009. Retrieved 2009-11-13.

- "Les cigarettes anti-incendie seront obligatoires en 2011". L'Express.fr (in French). L'Expansion. AFP. Archived from the original on February 23, 2009. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

According to a study made by European union in 16 European countries, 11,000 fires were due to cigarettes between 2005 and 2007. They caused 520 deaths and 1600 injuries.

- "European Union Pushes for Self-Extinguishing Cigarettes". Deutsche Welle. Deutsche Welle. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- "European Union Pushes for Self-Extinguishing Cigarettes". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 2009-01-01.

- O'Connell, Vanessa (2004-04-23). "U.S. Suit Alleges Philip Morris Hid Cigarette-Fire Risk". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2019-02-24.

Philip Morris began examining ways to make cigarettes less likely to cause fires in the early 1980s. The research initially was dubbed Project Hamlet, a joking reference to the line "to burn or not to burn," the company confirms.

- "Smoking article wrapper for controlling burn rate and method for making same - Philip Morris Incorporated". Freepatentsonline.com. Retrieved 2012-03-25.

- "NFPA :: Safety Information :: For consumers :: Causes :: Smoking :: Coalition for Fire-Safe Cigarettes". Firesafecigarettes.org. Retrieved 2012-03-25.

- "Method and apparatus for making banded smoking article wrappers - US Patent 5342484 Full Text". Patentstorm.us. Archived from the original on 2008-05-12. Retrieved 2012-03-25.

- "States that have passed fire-safe cigarette laws". Fire Safe Cigarettes. Retrieved 2012-03-25.

- "Les cigarettes anti-incendie seront obligatoires en 2011" (in French). Lexpansion.com. Archived from the original on 2009-02-23. Retrieved 2009-11-13.

- "A legal history of smoking in Canada". CBC News. 2012-11-09. Retrieved 2014-12-29.

On Jan. 19, 2005, The Supreme Court of Canada rules that Saskatchewan can reinstate a controversial law that forces store owners to keep tobacco products behind curtains or doors. The so-called "shower curtain law" was passed in 2002 to hide cigarettes from children, but was struck down a year later by an appeals court.

- "Ontario set to ban cigarette display cases". CTV News. 2008-04-20. Archived from the original on 2009-02-12. Retrieved 2009-01-31.

The new ban prevents all tobacco products from being displayed in any way and prohibits customers from even touching them before they're paid for.

- "A Proposal to Regulate the Display and Promotion of Tobacco and Tobacco-Related Products at Retail". Hc-sc.gc.ca. Archived from the original on June 7, 2011. Retrieved 2009-11-13.

- Harris, Gardiner (November 10, 2010). "F.D.A. Unveils Proposed Graphic Warning Labels for Cigarette Packs". The New York Times.

- Scollo, Michelle; Haslam, Indra (2008). A12.1.1.3 Pictorial warnings in force since 2006. Tobacco in Australia. Cancer Council Victoria. Retrieved 2010-07-23.

- Warning on cigarette pack. Tobacco in Pakistan.

- "Iceland Tough On Cigarettes – Sun Sentinel". Articles.sun-sentinel.com. 1985-09-17. Retrieved 2013-01-02.

- Bardi, Jason (2012-11-16). "Cigarette Pack Health Warning Labels in US Lag Behind World". Tobacco Control. 23 (1): e2. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050541. PMC 3725195. PMID 23092884. Retrieved 2013-01-02.

- Ottawa to increase size of tobacco warning to cover 3/4 of cigarette package https://vancouversun.com/health/Ottawa+increase+size+tobacco+warnings/4039002/story.html%5B%5D

- "Story of a shattered life: A single childhood incident pushed Dawn Crey into a downward spiral | Vancouver Sun". 2001-11-24. Retrieved February 19, 2011.

- "Tobacco Plain Packaging Regulations 2011". Australian Government Federal Register of Legislation. 2013-08-08. 2.2.1 (2) & passim. Retrieved 2018-03-29.

- "Australia unveils tough new cigarette pack rules". Channel NewsAsia. 2011-04-07. Retrieved 2012-03-25.

- "The world's ugliest colour has been revealed". The Independent. 2016-06-11. Retrieved 2016-06-19.

- "This new law could save your life". The Independent. 2016-05-20. Retrieved 2016-06-19.

- "Australia's Top Court Backs Plain-Pack Tobacco Laws". Bloomberg. August 15, 2012.

- Clean Virginia Waterways, Cigarette Butt Litter - Cigarette Filters Archived 2009-01-26 at the Wayback Machine, Longwood University. Retrieved October 31, 2006.

- Wigand, J.S. Additives, Cigarette Design and Tobacco Product Regulation, A Report To: World Health Organization, Tobacco Free Initiative, Tobacco Product Regulation Group, Kobe, Japan, 28 June-2 July 2006

- "Composite List of Ingredients in Non-Tobacco Materials". Archived from the original on May 24, 2008. www.jti.com. Retrieved November 2, 2006.

- David E. Merrill, (1994), "How cigarettes are made". Video presentation at Philip Morris USA, Richmond offices. Retrieved October 31, 2006.

- "Legacy Tobacco Documents Library". G2public.library.ucsf.edu. Archived from the original on February 12, 2009. Retrieved 2012-03-25.

- Grant Gellatly, "Method and apparatus for coating reconstituted tobacco".. Retrieved November 2, 2006.

- David Pemberton, "Spies, Smoking & Radiation Sickness". Archived from the original on 2014-02-25.

- STS Archived January 12, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- "13 Manufacturing Tobacco". Archived from the original on December 3, 2011.. Retrieved May 11, 2011.

- Seeman, Jeffrey I.; Carchman, Richard A. (2008). "The possible role of ammonia toxicity on the exposure, deposition, retention, and the bioavailability of nicotine during smoking". Food and Chemical Toxicology. 46 (6): 1863–81. doi:10.1016/j.fct.2008.02.021. PMID 18450355.

- "How to Roll Your Own Filter Cigarettes: 6 Steps (with Pictures)". wikihow.com. Archived from the original on 2014-02-22. Retrieved 2014-02-14.

- "Zig-Zag Filtered Cigarette Tubes, RYO Magazine, The Magazine of Roll Your Own Cigarettes, Reviews, the Premier filter tube, filtered cigarettes". ryomagazine.com. Retrieved 2014-02-14.

- "Forms Tutorial: Glossary Text Version". ttb.gov. Archived from the original on 2013-05-08. Retrieved 2014-02-14.

- Warne, M. St. J.; Warne, M. St. J.; Pablo, F.; Patra, R. (2005). "Variation in, and Causes of, Toxicity of Cigarette Butts to a Cladoceran and Microtox". Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology. 50 (2): 205–212. doi:10.1007/s00244-004-0132-y. PMID 16328625.

- Kathleen M. Register. "Cigarette Butts as Litter—Toxic as Well as Ugly", Longwood University. Retrieved 28 June 2011. First published in Underwater Naturalist, Volume 25, Number 2, August 2000.

- The Nelson contemporary English dictionary - Page 187, W. T. Cunningham - 1977

- "Penny for your butts? Vancouver group pushes cigarette-butt recycling plan". CTVNews. Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- City of Vancouver (2013-11-13). "City and TerraCycle launch cigarette butt collection and recycling program". Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- Novotny TE, Lum K, Smith E, et al. (2009). "Cigarettes butts and the case for an environmental policy on hazardous cigarette waste". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 6 (5): 1691–705. doi:10.3390/ijerph6051691. PMC 2697937. PMID 19543415.

- "The world litters 4.5 trillion cigarette butts a year. Can we stop this?". The Houston Chronicle. Retrieved 2014-09-16.

- "International Coastal Cleanup 2006 Report, page 8" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on November 26, 2008. Retrieved 2009-11-13.

- "CigaretteLitter.org". Archived from the original on 2007-05-22. Retrieved 2007-05-28.

- Slaughter E, Gersberg RM, Watanabe K, Rudolph J, Stransky C, Novotny TE (2011). "Toxicity of cigarette butts, and their chemical components, to marine and freshwater fish". Tobacco Control. 20 (Suppl_1): 25–29. doi:10.1136/tc.2010.040170. PMC 3088407. PMID 21504921.

- Pauly JL, Mepani AB, Lesses JD, Cummings KM, Streck RJ (March 2002). "Cigarettes with defective filters marketed for 40 years: what Philip Morris never told smokers". Tob Control. 11 (Suppl 1): I51–61. doi:10.1136/tc.11.suppl_1.i51. PMC 1766058. PMID 11893815.

Table 1 Chronology of events related to the marketing of cigarettes filters in the USA, and filter fiber and carbon particle "fall-out" assays of Phillip Morris, Inc Date Milestones and documents

- Dahlberg ER (April 11, 2006). "Cigarette Filters With Vegetation, soil, and Subterranean Environment". Saint Paul, Minnesota: Hamline University. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Cigarette butt 'causes $1m house fire'". News.smh.com.au. 2008-09-14. Retrieved 2009-11-13.

- "The Facts About Cigarette Butts and Litter - Fire Danger". CigaretteLitter.Org. Archived from the original on 2009-07-08. Retrieved 2009-11-13.

- Perkin, Corrie (2009-02-09). "Cigarette butt blamed for West Bendigo fire; two dead, 50 homes lost | Victoria". News.com.au. Archived from the original on February 25, 2009. Retrieved 2009-11-13.

- "Can cigarette butts start bushfires? - NSW Fire Brigades". Nswfb.nsw.gov.au. 2007-06-21. Archived from the original on 2009-10-17. Retrieved 2009-11-13.

- "Discarded cigarette butt causes airport chaos - ABC News (Australian Broadcasting Corporation)". Abc.net.au. 2009-01-15. Retrieved 2009-11-13.

- "British American Tobacco - Cigarettes". Bat.com. Archived from the original on March 3, 2012. Retrieved 2012-03-25.

- "Kicking butts". Retrieved 2014-09-16.

- Puls J, Wilson SA, Holter D (2011). "Degradation of Cellulose Acetate-Based Materials: A Review". Journal of Polymers and the Environment. 19: 152–165. doi:10.1007/s10924-010-0258-0.

- Ceredigion County Council Archived January 8, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- "Bulletin of the American Littoral Society, Volume 26, Number 2, August 2000". Longwood.edu. Retrieved 2009-11-13.

- Gou, JY; Miller, LM; Hou, G; Yu, XH; Chen, XY; Liu, CJ (January 2012). "Acetylesterase-mediated deacetylation of pectin impairs cell elongation, pollen germination, and plant reproduction". Plant Cell. 24 (1): 50–65. doi:10.1105/tpc.111.092411. PMC 3289554. PMID 22247250.

- "Breaking Down Cellulose". large.stanford.edu.

- Buchanan CM, Garder RM, Komarek RJ (1993). "Aerobic biodegradation of cellulose acetate". Journal of Applied Polymer Science. 47 (10): 1709–1719. doi:10.1002/app.1993.070471001.

- Rivard CJ, Adney WS, Himmel ME, Mitchell DJ, Vinzant TB, Grohmann K, Moens L, Chum H (1992). "Effects of Natural Polymer Acetlation on the anaerobic Dioconversion to Methane and Carbon Dioxide". Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology. 34/35: 725–736. doi:10.1007/bf02920592.

- Hon NS (1977). "Photodegradation of Cellulose Acetate Fibers". Journal of Polymer Science Part A: Polymer Chemistry. 15 (3): 725–744. Bibcode:1977JPoSA..15..725H. doi:10.1002/pol.1977.170150319.

- Hosono K, Kanazawa A, Mori H, Endo T (2007). "Photodegradation of Cellulose Acetate film in the presence of bensophenone as a photosensitizer". Journal of Applied Polymer Science. 105 (6): 3235–3239. doi:10.1002/app.26386.

- "Study on Photocatalytic Oxidation (PCO) Raises Questions About Formaldehyde as a Byproduct in Indoor Air". Archived from the original on 26 April 2015. Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- "photosensitization - chemistry". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- "Accidents, fires: Price of littering goes beyond fines". Washington: State of Washington Department of Ecology. 2004-06-01. Archived from the original on 2009-10-12. Retrieved 2009-05-06.

- "No more butts: biodegradable filters a step to boot litter problem". Environmental Health News. 2012-08-14.

- Novotny, Thomas; Lum, Kristen; Smith, Elizabeth; Wang, Vivian; Barnes, Richard (2009). "Cigarette Butts and the Case for an Environmental Policy on Hazardous Cigarette Waste". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 6 (5): 1691–1705. doi:10.3390/ijerph6051691. PMC 2697937. PMID 19543415.

- Minzae L, Gil-Pyo K, Hyeon DS, Soomin P, Jongheop Y (2014). "Preparation of energy storage material derived from a used cigarette filter for a supercapacitor electrode". Nanotechnology. 25 (34): 34. Bibcode:2014Nanot..25H5601L. doi:10.1088/0957-4484/25/34/345601. PMID 25092115. S2CID 8692351.

- Willingham, Richard (31 Dec 2010). "Tobacco display ban from tomorrow". The Age(Melbourne). Fairfax Media. Retrieved 2012-06-28.

- Ng, Marie; Freeman, Michael K.; Fleming, Thomas D.; Robinson, Margaret; Dwyer-Lindgren, Laura; Thomson, Blake; Wollum, Alexandra; Sanman, Ella; Wulf, Sarah (2014-01-08). "Smoking Prevalence and Cigarette Consumption in 187 Countries, 1980-2012". JAMA. 311 (2): 183–92. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.284692. ISSN 0098-7484. PMID 24399557.

- "The Global Cigarette Industry". August 2018.

- "Tobacco Merchant Account". Allied Payments. 2019-05-21. Retrieved 2018-05-25.

- Innis, Michelle (11 June 2014). "Australia's Graphic Cigarette Pack Warnings Appear to Work" – via NYTimes.com.

- "Age-standardized prevalence of current tobacco smoking among persons aged 15 years or older, 2016". 2018.

- Cigarette numbers and per capita consumption from The Tobacco Atlas: https://tobaccoatlas.org/topic/consumption/ Population numbers from World Bank 2017

- "NICOTINE, TAR, AND CO CONTENT OF DOMESTIC CIGARETTES". Archived from the original on 1 April 2012. Retrieved 5 October 2011.

- Koch 2009

- U.S. National 2004

- Benowitz 2005, p. 1

- NCI’s Smoking 2007, p.7

- SGUS 2016, p. 106; Chapter 3.

- "Why is it so hard to quit?". Heart.org. Retrieved 2012-03-25.

- "HEALTH | Cigarettes 'cut life by 11 minutes'". BBC News. 1999-12-31. Retrieved 2012-03-25.

- Shaw, M. (2000). "Time for a smoke? One cigarette reduces your life by 11 minutes". BMJ. 320: 53. doi:10.1136/bmj.320.7226.53. Retrieved 2012-03-25.

- "Tobacco". www.who.int. Retrieved 2019-07-17.

- "WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic" (PDF). World Health Organization. 2008.

- Kastan MB (2008). "DNA damage responses: mechanisms and roles in human disease: 2007 G.H.A. Clowes Memorial Award Lecture". Mol. Cancer Res. 6 (4): 517–24. doi:10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-08-0020. PMID 18403632.

- Cunningham FH, Fiebelkorn S, Johnson M, Meredith C (2011). "A novel application of the Margin of Exposure approach: segregation of tobacco smoke toxicants". Food Chem. Toxicol. 49 (11): 2921–33. doi:10.1016/j.fct.2011.07.019. PMID 21802474.

- Liu XY, Zhu MX, Xie JP (2010). "Mutagenicity of acrolein and acrolein-induced DNA adducts". Toxicol. Mech. Methods. 20 (1): 36–44. doi:10.3109/15376510903530845. PMID 20158384.

- Speit G, Merk O (2002). "Evaluation of mutagenic effects of formaldehyde in vitro: detection of crosslinks and mutations in mouse lymphoma cells". Mutagenesis. 17 (3): 183–7. doi:10.1093/mutage/17.3.183. PMID 11971987.

- Pu X, Kamendulis LM, Klaunig JE (2009). "Acrylonitrile-induced oxidative stress and oxidative DNA damage in male Sprague-Dawley rats". Toxicol. Sci. 111 (1): 64–71. doi:10.1093/toxsci/kfp133. PMC 2726299. PMID 19546159.

- Koturbash I, Scherhag A, Sorrentino J, Sexton K, Bodnar W, Swenberg JA, Beland FA, Pardo-Manuel Devillena F, Rusyn I, Pogribny IP (2011). "Epigenetic mechanisms of mouse interstrain variability in genotoxicity of the environmental toxicant 1,3-butadiene". Toxicol. Sci. 122 (2): 448–56. doi:10.1093/toxsci/kfr133. PMC 3155089. PMID 21602187.

- Garcia CC, Angeli JP, Freitas FP, Gomes OF, de Oliveira TF, Loureiro AP, Di Mascio P, Medeiros MH (2011). "[13C2]-Acetaldehyde promotes unequivocal formation of 1,N2-propano-2'-deoxyguanosine in human cells". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133 (24): 9140–3. doi:10.1021/ja2004686. PMID 21604744.

- Tompkins EM, McLuckie KI, Jones DJ, Farmer PB, Brown K (2009). "Mutagenicity of DNA adducts derived from ethylene oxide exposure in the pSP189 shuttle vector replicated in human Ad293 cells". Mutat. Res. 678 (2): 129–37. doi:10.1016/j.mrgentox.2009.05.011. PMID 19477295.