Porton Down

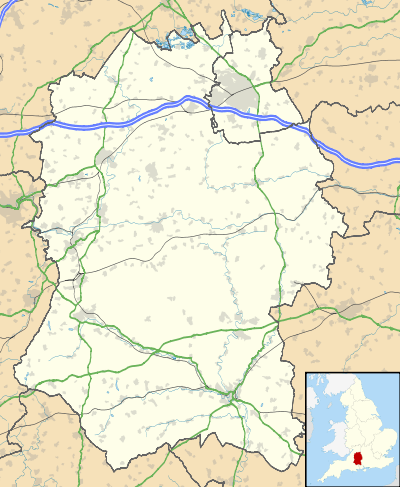

Porton Down is a science park in Wiltshire, England, just northeast of the village of Porton, near Salisbury. It is home to two British government facilities: a site of the Ministry of Defence's Defence Science and Technology Laboratory (Dstl) – known for over 100 years as one of the UK's most secretive and controversial military research facilities, occupying 7,000 acres (2,800 ha)[1] – and a site of Public Health England.[2] It is also home to other private and commercial science organisations, and is expanding to attract other companies.

Entrance to secure facilities at Porton Down | |

| |

| Location | Northeast of the village of Porton near Salisbury, in Wiltshire, England |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 51.131°N 1.704°W |

| Opening date | March 1916 |

| Size | 7,000 acres (2,800 ha) |

Location

Porton Down is located just northeast of the village of Porton near Salisbury, in Wiltshire, England. To the northwest lies the MoD Boscombe Down airfield operated by QinetiQ. On some maps, the land surrounding the complex is identified as a "Danger Area".[3]

History of government use

Porton Down opened in 1916 as the War Department Experimental Station, shortly thereafter renamed the Royal Engineers Experimental Station, for testing chemical weapons in response to German use of this means of war in 1915. The laboratory's remit was to conduct research and development regarding chemical weapons agents used by the British armed forces in the First World War, such as chlorine, mustard gas, and phosgene.[4]

Work at Porton started in March 1916. At the time, only a few cottages and farm buildings were scattered on the downs at Porton and Idmiston. By May 1917, the focus for anti-gas defence and respirator development had moved from London to Porton Down, and by 1918, the original two huts had become a large hutted camp with 50 officers and 1,100 other ranks. After the Armistice in 1918, Porton Down was reduced to a skeleton staff.[5]

Post First World War

In 1919, the War Office set up the Holland Committee to consider the future of chemical warfare and defence. By 1920, the Cabinet agreed to the Committee's recommendation that work would continue at Porton Down. From that date a slow permanent building programme began, coupled with the gradual recruitment of civilian scientists. By 1922, there were 380 servicemen, 23 scientific and technical civil servants, and 25 "civilian subordinates". By 1925, the civilian staff had doubled.[5]

By 1926, the chemical defence aspects of Air Raid Precautions (ARP) for the civilian population was added to the Station's responsibilities. In 1929 the Royal Engineers Experimental Station became the Chemical Warfare Experimental Station (CWES) (1929–1930), and in 1930 the Chemical Defence Experimental Station (CDES) (1930–1948).[5] In 1930 Britain ratified the 1925 Geneva Protocol with reservations, which permitted the use of chemical warfare agents only in retaliation. By 1938, the international situation was such that the Cabinet authorised offensive chemical warfare research and development and the production of war reserve stocks of chemical warfare agents by the chemical industry.[5]

Second World War

During the Second World War, research at CDES concentrated on chemical weapons such as nitrogen mustard. As Allied armies penetrated Germany, they discovered operational stockpiles of munitions and weapons that contained new chemical warfare agents, including highly toxic organophosphorous nerve agents such as sarin, unknown to Britain and the Allies at the time.[5]

To examine biological weapons, a highly secret separate department, called the Biology Department, Porton (BDP), was established within CDES in 1940, under veteran microbiologist Paul Fildes. Its focus included anthrax and botulinum toxin, and in 1942 it famously carried out tests of an anthrax bio-weapon at Gruinard Island. In 1946, it was renamed the Microbiological Research Department (MRD) and, in 1957, the Microbiological Research Establishment (MRE).

The Common Cold Unit (CCU) was sometimes confused with the MRE, with which it occasionally collaborated but was not officially connected. The CCU was located at Harvard Hospital, Harnham Down, on the west side of Salisbury.[5]

Post-war period

When the Second World War ended, the advanced state of German technology regarding the organophosphorous nerve agents, such as tabun, sarin and soman, had surprised the Allies, who were eager to capitalise on it. Subsequent research took the newly discovered German nerve agents as a starting point, and eventually VX nerve agent was developed at Porton Down in 1952.[5]

In the late 1940s and early 1950s, research and development at Porton Down was aimed at providing Britain with the means to arm itself with a modern nerve agent-based capability and to develop specific means of defence against these agents. In the end these aims came to nothing on the offensive side because of the decision to abandon any sort of British chemical warfare capability in favour of nuclear weapons. On the defensive side there were years of difficult work to develop the means of prophylaxis, therapy, rapid detection and identification, decontamination, and more effective protection of the body against nerve agents, capable of exerting effects through the skin, the eyes and respiratory tract.[5]

Tests were carried out on servicemen to determine the effects of nerve agents on human subjects, with one recorded death due to a nerve gas experiment. There have been persistent allegations of unethical human experimentation at Porton Down, such as those relating to the death of Leading Aircraftman Ronald Maddison, aged 20, in 1953. Maddison was taking part in sarin nerve agent toxicity tests; sarin was dripped onto his arm and he died shortly afterwards.

In the 1950s, the station, now renamed the Chemical Defence Experimental Establishment (CDEE), became involved with the development of CS, a riot-control agent, and took an increasing role in trauma and wound ballistics work. Both these facets of Porton Down's work had become more important because of the unrest and increasing violence in Northern Ireland.[5]

On 1 August 1962, Geoffrey Bacon, a scientist at the Microbiological Research Establishment, died from an accidental infection of the plague bacterium Yersinia pestis. In the same month an autoclave exploded, shattering two windows. Both incidents generated considerable media coverage at the time.[5]

In 1970, the senior establishment at Porton Down was renamed the Chemical Defence Establishment (CDE) for the next 21 years. Preoccupation with defence against nerve agents continued, but in the 1970s and 1980s, the Establishment was also concerned with studying reported chemical warfare by Iraq against Iran and against its own Kurdish population.[5]

Porton Down was the laboratory where initial samples of the Ebola virus were sent in 1976 during the first confirmed outbreak of the disease in Africa. The laboratory now contains samples of some of the world's most aggressive pathogens, including Ebola, anthrax and the plague, and is leading the UK's current research into viral inoculations.[6]

21st century

Until 2001 the military installation of Porton Down was part of the UK government's Defence Evaluation and Research Agency (DERA) when it was split into QinetiQ, initially a fully government-owned company, and the Defence Science and Technology Laboratory (Dstl). Dstl incorporates all of DERA's activities deemed unsuitable for the privatisation planned for QinetiQ, particularly Porton Down.

In 2013 Dstl scientists tested samples from Syria for sarin, which is still manufactured there, to test soldiers' equipment.[1]

Public Health England have planned since September 2015[7] to transfer their Porton Down staff to Harlow, and in July 2017 it had bought a vacant site from GSK (GlaxoSmithKline), aiming to consolidate operations there in 2024[8]

Site names

The location's government use has been split into two separately controlled locations since 1979: the original military establishment under the Ministry of Defence, and the site to the south under the Department of Health, which had been opened in 1951 for the Microbiological Research Establishment, then in 1979 transferred to the Ministry of Health to focus on public health research, with the Defence aspects returning to the then-titled Chemical Defence Establishment.[9]

| Date | Ministry of Defence (and predecessors) | Department of Health | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1916 | War Department Experimental Station | ||

| 1916-29 | Royal Engineers Experimental Station | ||

| 1929-30 | Chemical Warfare Experimental Station (CWES) | ||

| 1930-48 | Chemical Defence Experimental Station (CDES) | ||

| 1940-46 | Biology Department Porton (BDP) | ||

| 1946-48 | Microbiological Research Department (MRD) | ||

| 1948-57 | Chemical Defence Experimental Establishment (CDEE) | ||

| 1957-70 | Microbiological Research Establishment (MRE) | ||

| 1970-79 | Chemical Defence Establishment (CDE) | ||

| 1979-91 | Centre for Applied Microbiology & Research (CAMR) | ||

| 1991-95 | Chemical & Biological Defence Establishment (CBDE) | ||

| 1995-2001 | Chemical & Biological Defence Sector of DERA (CBD) | ||

| 2001-04 | (one site of) Defence Science and Technology Laboratory (Dstl) | ||

| 2004-13 | (one site of) Health Protection Agency | ||

| 2013–present | (one site of) Public Health England (PHE) | ||

Associated locations

Sutton Oak, Merseyside

A factory in Sutton Oak, St Helens was requisitioned in 1917 by the War Department, renamed HM Factory, Sutton Oak and started producing the chemical warfare agent diphenyl chloroarsine. The site switched to producing Adamsite in 1922. In 1923 the War Office halted the requisition and purchased the site, renaming it the War Office Research Establishment, a.k.a. Chemical Warfare Research Establishment, and later the Chemical Defence Research Establishment Sutton Oak. During the 1920s, the site switched to producing mustard gas products, starting with the HS variant and adding the HT variant in the 1930s, and also filling armaments. After WW2, the site also produced the nerve agent sarin for experimental purposes. The site closed in 1957, with much of the work transferring to Chemical Defence Establishment Nancekuke.[10]

RRH Portreath, Cornwall

This Royal Air Force site, built in 1940, was renamed Chemical Defence Establishment Nancekuke in July 1949. Manufacture of sarin in a pilot production facility commenced there in the early 1950s, producing about 20 tons from 1954 until 1956. It was intended as a stockpile and production facility for the UK's chemical defences during the Cold War, focussed on nerve agents, including small amounts of VX intended mainly for laboratory test purposes and to validate plant designs and optimise chemical processes for potential mass-production; full-scale production of VX agent never took place. In the late 1950s, the chemical weapons production plant was mothballed, but was maintained through the 1960s and 1970s in a state whereby production could easily re-commence if required.[11]

Non-government use

A few small scientific start-ups were allowed to use buildings on the Porton Down campus from the mid-1990s. Porton Down has been housing companies on Tetricus Science Park,[12] including Ploughshare Innovations since 2005,[13] and GW Pharmaceuticals.[12] As of 2014, an expansion plan was predicted to create 2,000 jobs.[14] Expansion started in 2016, with £9.5m in funding from Wiltshire Council, the Swindon and Wiltshire Local Enterprise Partnership and the European Regional Development Fund.[15][16]

Areas of concern

Trials

Open air

In 1942, Gruinard Island was dangerously contaminated with anthrax after a cloud of anthrax spores was released over the island during a trial. In 1981, a team of activists landed on the island and collected soil samples, a bag of which was left at the door at Porton Down. Testing showed that it still contained anthrax spores and in 1986 the Government felt obliged to take necessary steps to successfully decontaminate the island.

Between 1963 and 1975 the MRE carried out trials in Lyme Bay in which live bacteria were sprayed from a ship to be carried ashore by the wind to simulate an anthrax attack. The bacteria sprayed were the less dangerous Bacillus globigii and Escherichia coli, but it was later admitted that the bacteria could adversely affect some vulnerable people. The town of Weymouth lay downwind of the spraying. When the trials became public knowledge in the late 1990s, Dorset County Council, Weymouth and Portland Borough Council and Purbeck District Council demanded a public inquiry to investigate the experiments. The Government refused a Public Inquiry but instead commissioned Professor Brian Spratt, to conduct an Independent Review of the possible adverse health effects. He concluded that individuals with certain chronic conditions may have been affected.[17]

Human trials

Porton Down has been involved in human testing at various points throughout the Ministry of Defence's use of the site. Up to 20,000 people took part in various trials from 1949 up to 1989:[18]

From 1999 until 2006, it was investigated under Operation Antler. In 2002 a first inquest and[19] in May 2004, a second inquest into the death of Ronald Maddison during testing of the nerve agent sarin commenced after his relatives and their supporters had lobbied for many years, which found his death to have been unlawful.[20] The Ministry of Defence challenged the verdict[21] which was upheld and the government settled the case in 2006.[22] In 2006, 500 veterans claimed they suffered from the experiments.[23]

In February 2006, three ex-servicemen were awarded compensation in an out-of-court settlement after they had claimed they were given LSD without their consent during the 1950s.[18][24] In 2008, the MoD paid 360 veterans of the tests £3m without admitting liability.[1]

Secrecy

Most of the work carried out at Porton Down has to date remained secret. Bruce George, Member of Parliament and Chairman of the Defence Select Committee, told BBC News on 20 August 1999 that:

I would not say that the Defence Committee is micro-managing either DERA or Porton Down. We visit it, but, with eleven members of Parliament and five staff covering a labyrinthine department like the Ministry of Defence and the Armed Forces, it would be quite erroneous of me and misleading for me to say that we know everything that's going on in Porton Down. It's too big for us to know, and secondly, there are many things happening there that I'm not even certain Ministers are fully aware of, let alone Parliamentarians.[25]

Cannabis cultivation

The biotechnology company GW Pharmaceuticals, which researches and develops cannabinoid formulations as potential therapeutics,[26] has a facility at the Tetricus Science Park on the Porton Down site.[12] Most of the cannabis plants used by GW Pharmaceuticals are cultivated by British Sugar at their site in Norfolk.[27] Dstl state that "Dstl and its predecessors do not and have never grown cannabis at Porton Down."[28]

Use of animals

Dstl's Porton Down site conducts animal testing. The "three Rs" of "reduce" (the number of animals used), "refine" (animal procedures) and "replace" (animal tests with non-animal tests) are used as the basic code of practice.[29] There has been a decrease in animal experimentation in recent years.[30] Dstl complies with all UK legislation relating to animals.[31] Animals used include mice, guinea pigs, rats, pigs, ferrets, sheep, and non-human primates (believed to be marmosets and rhesus macaque). Publicly released figures are detailed below:

| Animals used at Porton Down by DERA (1997–2001) / Dstl (2001–2015) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 |

| Number | 10956[32] | 11091[32] | 11501[32] | 11985[33] | 12955[33] | 15940[33] | 13899[33] | 15728[33] | 21118[33] | 17041[34] | 18255[34] |

| Year | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | |

| Number | 12373[34] | 8452[34] | 9438[35] | 9722[35] | 8830[35] | 6461[35] | 4124[36] | 3249[37] | 2745[38] | 3865[39] | |

Different departments at Porton Down use animal experiments in different ways. Dstl's Biomedical Sciences department is involved with drug evaluation and efficacy testing (toxicology, pharmacology, physiology, behavioural science, human science), trauma and surgery studies, and animal breeding. The Physical Sciences department also uses animals in its "Armour Physics" research.

Like other aspects of research at Porton Down, precise details of animal experiments are generally kept secret. Media reports have suggested they include exposing monkeys to anthrax, draining the blood of pigs and injecting them with E. coli bacteria, and exposing animals to a variety of lethal, toxic nerve agents. Different animals are used for very different purposes. According to a 2002 report from the Animal Welfare Advisory Committee of the Ministry of Defence, mice are used mainly to research "the development of vaccines and treatments for microbial and viral infections", while pigs are used to "develop personal protective equipment to protect against blast injury to the thorax".[40]

In popular culture

Novels

- An institute similar to Porton Down, the Mordon Microbiological Research Establishment, features in the 1962 novel The Satan Bug by Alistair MacLean.

- Porton Down features in the 1977 novel The Enemy by Desmond Bagley, and the 2010 mystery novel Before the Poison by Peter Robinson.

Television

- Porton Down and activities there during the 1940s and early 1950s were a significant plot point in Episodes One and Two of the second season of ITV's mystery series The Bletchley Circle.

- Experiments conducted at Porton Down also appear in the BBC detective drama Spooks, including the development of the VX Nerve Agent and other potentially deadly biological weapons.

- Porton Down was referenced frequently in the 2020 BBC TV drama The Salisbury Poisonings, portraying its role in testing substances linked to the 2018 poisoning of Sergei and Yulia Skripal.

Comics

- Grimbledon Down was a comic strip by British cartoonist Bill Tidy, published for many years by New Scientist. The strip was set in an ostensibly fictitious UK government research lab, referring to the controversial Porton Down bio-chemical research facility.[41]

Film

- Porton Down will be a location in the forthcoming James Bond film No Time to Die. A set representing a laboratory was built on the 007 Stage at Pinewood Studios in 2019.[42]

Music

- "Porton Down" is the name of a song by Peter Hammill.

- The song "Jeopardy" by Skyclad is about the experiments developed in Porton Down.

See also

- The United Kingdom and weapons of mass destruction

- CDE Nancekuke - manufacturing outstation of Chemical Defence Establishment, 1950s and 60s.

- Boscombe Down and Defence CBRN Centre- neighbouring facilities.

- David Kelly, Lancelot Ware - notable individuals connected to Porton Down.

- Rawalpindi experiments - experiments involving the use of mustard gas carried out on British and Indian soldiers in the 1930s.

- Keen as Mustard, a documentary film on British and American WWII mustard gas tests in tropical Australia in the 1940s

- Operation Vegetarian - British military plan to disseminate linseed cakes infected with anthrax spores onto the fields of Germany in 1942.

- Dugway Proving Ground and Fort Detrick - comparable facilities in the United States of America.

- Poisoning of Sergei and Yulia Skripal

References

- Porton Down: A Brief History by G B Carter, Porton Down's official historian.

- Chemical and Biological Defence at Porton Down 1916–2000 (The Stationery Office, 2000). by G B Carter

- Cold War, Hot Science: Applied Research in Britain's Defence Laboratories, 1945–1990 by Bud & Gummett

Notes

- Michael Mosley (28 June 2016). "Inside Britain's secret weapons research facility". BBC News.

- "Porton food, water and environmental laboratory". gov.uk. Public Health England. Retrieved 18 September 2015.

- "Ordnance Survey map number '184' of the 'Landranger' series of maps". Online Ordnance Survey.

- "War Office, Ministry of Supply, Ministry of Defence : Chemical Defence Experimental Establishment, later Chemical and Biological Defence Establishment, Porton: Reports and Technical Papers" (5136 files and volumes). The National Archives. 1918–1993. Retrieved 17 June 2017.CS1 maint: date format (link)

- Carter, G B (2000). Chemical and Biological Defence at Porton Down 1916-2000. London: The Stationery Office. pp. 126–127. ISBN 0-11-772933-7.

- "The front line of the UK's Ebola prevention efforts". BBC News. Retrieved 18 September 2015.

- Public Health England to move from Porton Down in Wiltshire itv.com. 17 September 2015

- Harlow site to be home to government's public health arm BBC News,9 July 2017

- Hammond, P; Carter, G (2001). From Biological Warfare to Healthcare: Porton Down, 1940-2000 (1st ed.). Palgrave Macmillan UK. p. 280. ISBN 9780333753835.

- "Magnum Poison Gas Works". suttonbeauty.org. Retrieved 29 June 2016.

- "Nancekuke Remediation Project". Ministry of Defence (Archived by The National Archives). Archived from the original on 8 December 2010. Retrieved 25 April 2012.

- "Tetricus Science Park". The United Kingdom Science Park Association. n.d. Archived from the original on 18 August 2017. Retrieved 17 August 2017.

- Ploughshare Innovations Ltd

- "Science park in Wiltshire wins £2m in council funding". BBC News: Wiltshire. 8 October 2014. Retrieved 22 April 2017.

- "Work begins on multi-million pound science park for Wiltshire". Wiltshire Council. 12 December 2016. Retrieved 22 April 2017.

- "Porton Science Park". The United Kingdom Science Park Association. Retrieved 22 April 2017.

- "The Dorset Biological Warfare Experiments 1963-75". Retrieved 17 June 2017.

- "MI6 payouts over secret LSD tests". BBC News. 24 February 2006.

- Nerve gas inquest to be re-opened BBC News report, 18 November 2002

- "Nerve gas death was 'unlawful'". BBC News. 15 November 2004.

- "MoD 'can challenge Porton case'". BBC News. 19 April 2005.

- "MoD agrees sarin case settlement". BBC News. 13 February 2006.

- David Shukman MOD pays out over nerve gas death BBC News, 25 May 2006

- Evans, Rob (24 February 2006). "MI6 pays out over secret LSD mind control tests". The Guardian.

- "Chemical base 'too big', says MP". BBC News. 20 August 1999.

- "GW Pharmaceuticals - History & Approach". Retrieved 17 August 2017.

- Bradshaw, Julia (11 February 2017). "UK set for cannabis boom as GW Pharma storms ahead". The Telegraph. Retrieved 18 August 2017.

- "The Truth About Porton Down". Gov.UK. Defence Science and Technology Laboratory. 27 June 2016. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

- "House of Commons Hansard Written Answers for 14 Sep 2010 (pt 0001)".

- "House of Commons Hansard Written Answers for 23 Mar 2010 (pt 0002)".

- "House of Commons Hansard Written Answers for 24 Mar 2010 (pt 0001)".

- (Hansard), Department of the Official Report; Commons, House of; Westminster (4 June 2003). "House of Commons Hansard Written Answers for 4 Jun 2003 (pt 14)". publications.parliament.uk. Retrieved 21 December 2017.

- (Hansard), Department of the Official Report; Commons, House of; Westminster (8 May 2006). "House of Commons Hansard Written Answers for 08 May 2006 (pt 0007)". publications.parliament.uk. Retrieved 21 December 2017.

- (Hansard), Department of the Official Report; Commons, House of; Westminster (29 January 2013). "House of Commons Hansard Written Answers for 29 Jan 2013 (pt 0002)". publications.parliament.uk. Retrieved 21 December 2017.

- (Hansard), Department of the Official Report; Commons, House of; Westminster (22 July 2014). "House of Commons Hansard Written Answers for 22 July 2014 (pt 0001)". publications.parliament.uk. Retrieved 21 December 2017.

- Barnett, Helen (27 June 2015). "REVEALED: Defence chiefs' animal testing shame as thousands suffer with EBOLA and PLAGUE". Express.co.uk. Retrieved 21 December 2017.

- "Porton Down: Animal Experiments:Written question - 43677". UK Parliament. 4 June 2014. Retrieved 21 December 2017.

- "FOI: Request number of animals used in research in Defence Science and Technology Laboratory in 2016 and copies of minutes of Internal Review Committee meetings" (PDF). UK Government.

- "FOI: Number of animals used in Defence Science and Technology Laboratory research for 2017" (PDF). UK Government.

- "Sixth Report of the Animal Welfare Advistory Committee" (PDF). February 2002. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 May 2006. Retrieved 1 March 2016.

- Hammond, Peter M.; Carter, Gradon (2002). From Biological Warfare to Healthcare: Porton Down 1940–2000. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 1. ISBN 9780230287211.

- "James Bond 25 set explosion", Express.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Porton Down. |

- DSTL Official Website

- Porton Down Cold War Research Project, 1945-1989 University of Kent, 28 January 2010

- Wiltshire police Operation Antler information

- Letter from the Department of Health to Health Authorities regarding the Porton Down volunteers 2005

- Archive of the month - Gaddum Papers Pharmacology and war: the papers of Sir John Henry Gaddum, March 2007, Royal Society

- Inside Porton Down: Britain's Secret Weapons Research Facility – television programme, BBC Four, 28 June 2016