Small interfering RNA

Small interfering RNA (siRNA), sometimes known as short interfering RNA or silencing RNA, is a class of double-stranded RNA non-coding RNA molecules, typically 20-27 base pairs in length, similar to miRNA, and operating within the RNA interference (RNAi) pathway. It interferes with the expression of specific genes with complementary nucleotide sequences by degrading mRNA after transcription, preventing translation.[1]

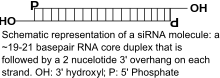

Structure

Naturally occurring siRNAs have a well-defined structure: a short (usually 20 to 24-bp) double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) with phosphorylated 5' ends and hydroxylated 3' ends with two overhanging nucleotides. The Dicer enzyme catalyzes production of siRNAs from long dsRNAs and small hairpin RNAs.[2] siRNAs can also be introduced into cells by transfection. Since in principle any gene can be knocked down by a synthetic siRNA with a complementary sequence, siRNAs are an important tool for validating gene function and drug targeting in the post-genomic era.

Mechanism

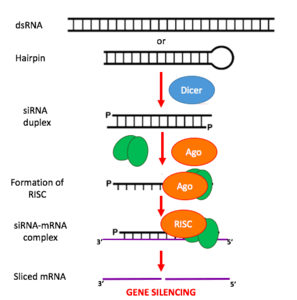

The mechanism by which natural siRNA causes gene silencing through repression of translation occurs as follows:

- Long dsRNA (which can come from hairpin, complementary RNAs, and RNA-dependent RNA polymerases) is cleaved by an endo-ribonuclease called Dicer. Dicer cuts the long dsRNA to form short interfering RNA or siRNA; this is what enables the molecules to form the RNA-Induced Silencing Complex (RISC).

- Once siRNA enters the cell it gets incorporated into other proteins to form the RISC.

- Once the siRNA is part of the RISC complex, the siRNA is unwound to form single stranded siRNA.

- The strand that is thermodynamically less stable due to its base pairing at the 5´end is chosen to remain part of the RISC-complex

- The single stranded siRNA which is part of the RISC complex now can scan and find a complementary mRNA

- Once the single stranded siRNA (part of the RISC complex) binds to its target mRNA, it induces mRNA cleavage.

- The mRNA is now cut and recognized as abnormal by the cell. This causes degradation of the mRNA and in turn no translation of the mRNA into amino acids and then proteins. Thus silencing the gene that encodes that mRNA.

siRNA is also similar to miRNA, however, miRNAs are derived from shorter stemloop RNA products, typically silence genes by repression of translation, and have broader specificity of action, while siRNAs typically work by cleaving the mRNA before translation, and have 100% complementarity, thus very tight target specificity.[3]

RNAi induction using siRNAs or their biosynthetic precursors

Gene knockdown by transfection of exogenous siRNA is often unsatisfactory because the effect is only transient, especially in rapidly dividing cells. This may be overcome by creating an expression vector for the siRNA. The siRNA sequence is modified to introduce a short loop between the two strands. The resulting transcript is a short hairpin RNA (shRNA), which can be processed into a functional siRNA by Dicer in its usual fashion.[4] Typical transcription cassettes use an RNA polymerase III promoter (e.g., U6 or H1) to direct the transcription of small nuclear RNAs (snRNAs) (U6 is involved in gene splicing; H1 is the RNase component of human RNase P). It is theorized that the resulting siRNA transcript is then processed by Dicer.

The gene knockdown efficiency can also be improved by using cell squeezing.[5]

The activity of siRNAs in RNAi is largely dependent on its binding ability to the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC). Binding of the duplex siRNA to RISC is followed by unwinding and cleavage of the sense strand with endonucleases. The remaining anti-sense strand-RISC complex can then bind to target mRNAs for initiating transcriptional silencing.[6]

RNA activation

It has been found that dsRNA can also activate gene expression, a mechanism that has been termed "small RNA-induced gene activation" or RNAa. It has been shown that dsRNAs targeting gene promoters induce potent transcriptional activation of associated genes. RNAa was demonstrated in human cells using synthetic dsRNAs, termed "small activating RNAs" (saRNAs). It is currently not known whether RNAa is conserved in other organisms.[7]

Post-transcriptional gene silencing

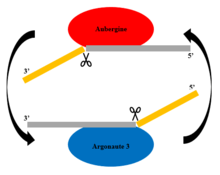

The siRNA induced post transcriptional gene silencing starts with the assembly of the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC). The complex silences certain gene expression by cleaving the mRNA molecules coding the target genes. To begin the process, one of the two siRNA strands, the guide strand (anti-sense strand), will be loaded into the RISC while the other strand, the passenger strand (sense strand), is degraded. Certain Dicer enzymes may be responsible for loading the guide strand into RISC.[8] Then, the siRNA scans for and directs RISC to perfectly complementary sequence on the mRNA molecules.[9] The cleavage of the mRNA molecules is thought to be catalyzed by the Piwi domain of Argonaute proteins of the RISC. The mRNA molecule is then cut precisely by cleaving the phosphodiester bond between the target nucleotides which are paired to siRNA residues 10 and 11, counting from the 5’end.[10] This cleavage results in mRNA fragments that are further degraded by cellular exonucleases. The 5’ fragment is degraded from its 3’ end by exosome while the 3’ fragment is degraded from its 5’ end by 5' -3' exoribonuclease 1(XRN1).[11] Dissociation of the target mRNA strand from RISC after the cleavage allow more mRNA to be silenced. This dissociation process is likely to be promoted by extrinsic factors driven by ATP hydrolysis.[10]

Sometimes cleavage of the target mRNA molecule does not occur. In some cases, the endonucleolytic cleavage of the phosphodiester backbone may be suppressed by mismatches of siRNA and target mRNA near the cleaving site. Other times, the Argonaute proteins of the RISC lack endonuclease activity even when the target mRNA and siRNA are perfectly paired.[10] In such cases, gene expression will be silenced by an miRNA induced mechanism instead.[9]

Piwi-interacting RNAs are responsible for the silencing of transposons and are not siRNAs.[12]

Challenges: avoiding nonspecific effects

Because RNAi intersects with a number of other pathways, it is not surprising that on occasion nonspecific effects are triggered by the experimental introduction of an siRNA.[13][14] When a mammalian cell encounters a double-stranded RNA such as an siRNA, it may mistake it as a viral by-product and mount an immune response. Furthermore, because structurally related microRNAs modulate gene expression largely via incomplete complementarity base pair interactions with a target mRNA, the introduction of an siRNA may cause unintended off-targeting. Chemical modifications of siRNA may alter the thermodynamic properties that also result in a loss of single nucleotide specificity.[15]

Innate immunity

Introduction of too much siRNA can result in nonspecific events due to activation of innate immune responses.[16] Most evidence to date suggests that this is probably due to activation of the dsRNA sensor PKR, although retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I) may also be involved.[17] The induction of cytokines via toll-like receptor 7 (TLR7) has also been described. Chemical modification of siRNA is employed to reduce in the activation of the innate immune response for gene function and therapeutic applications. One promising method of reducing the nonspecific effects is to convert the siRNA into a microRNA.[18] MicroRNAs occur naturally, and by harnessing this endogenous pathway it should be possible to achieve similar gene knockdown at comparatively low concentrations of resulting siRNAs. This should minimize nonspecific effects.

Off-targeting

Off-targeting is another challenge to the use of siRNAs as a gene knockdown tool[14]. Here, genes with incomplete complementarity are inadvertently downregulated by the siRNA (in effect, the siRNA acts as a miRNA), leading to problems in data interpretation and potential toxicity. This, however, can be partly addressed by designing appropriate control experiments, and siRNA design algorithms are currently being developed to produce siRNAs free from off-targeting. Genome-wide expression analysis, e.g., by microarray technology, can then be used to verify this and further refine the algorithms. A 2006 paper from the laboratory of Dr. Khvorova implicates 6- or 7-basepair-long stretches from position 2 onward in the siRNA matching with 3'UTR regions in off-targeted genes.[19]

Adaptive immune responses

Plain RNAs may be poor immunogens, but antibodies can easily be created against RNA-protein complexes. Many autoimmune diseases see these types of antibodies. There haven't yet been reports of antibodies against siRNA bound to proteins. Some methods for siRNA delivery adjoin polyethylene glycol (PEG) to the oligonucleotide reducing excretion and improving circulating half-life. However recently a large Phase III trial of PEGylated RNA aptamer against factor IX had to be discontinued by Regado Biosciences because of a severe anaphylactic reaction to the PEG part of the RNA. This reaction led to death in some cases and raises significant concerns about siRNA delivery when PEGylated oligonucleotides are involved.[20]

Saturation of the RNAi machinery

siRNAs transfection into cells typically lowers the expression of many genes, however, the upregulation of genes is also observed. The upregulation of gene expression can partially be explained by the predicted gene targets of endogenous miRNAs. Computational analyses of more than 150 siRNA transfection experiments support a model where exogenous siRNAs can saturate the endogenous RNAi machinery, resulting in the de-repression of endogenous miRNA-regulated genes.[21] Thus, while siRNAs can produce unwanted off-target effects, i.e. unintended downregulation of mRNAs via a partial sequence match between the siRNA and target, the saturation of RNAi machinery is another distinct nonspecific effect, which involves the de-repression of miRNA-regulated genes and results in similar problems in data interpretation and potential toxicity.[22]

Chemical modification

siRNAs have been chemically modified to enhance their therapeutic properties, such as enhanced activity, increased serum stability, fewer off-targets and decreased immunological activation. A detailed database of all such chemical modifications is manually curated as siRNAmod in scientific literature.[23] Chemical modification of siRNA can also inadvertently result in loss of single-nucleotide specificity.[24]

History

siRNAs and their role in post-transcriptional gene silencing (PTGS) were first discovered in plants by David Baulcombe's group at the Sainsbury Laboratory in Norwich, England and reported in Science in 1999.[25] Thomas Tuschl and colleagues soon reported in Nature that synthetic siRNAs could induce RNAi in mammalian cells.[26] This discovery led to a surge in interest in harnessing RNAi for biomedical research and drug development. Significant developments in siRNA therapies have been made with both organic (carbon based) and inorganic (non-carbon based) nanoparticles, such as these which have been successful in drug delivery to the brain, offering promising methods of delivery into human subjects. However, significant barriers to successful siRNA therapies remain, the most significant of which is off-targeting.[27]

Therapeutic applications and challenges

Given the ability to knock down, in essence, any gene of interest, RNAi via siRNAs has generated a great deal of interest in both basic[28] and applied biology.

One of the biggest challenges to siRNA and RNAi based therapeutics is intracellular delivery.[29] Delivery of siRNA via nanoparticles has shown promise.[27][29] siRNA oligos in vivo are vulnerable to degradation by plasma and tissue nucleases[27] and have shown only mild effectiveness in localized delivery sites, such as the human eye.[30] Delivering pure DNA to target organisms is challenging because its large size and structure prevents it from diffusing readily across membranes.[29] siRNA oligos circumvent this problem due to their small size of 21-23 oligos.[31] This allows delivery via nano-scale delivery vehicles called nanovectors.[30]

A good nanovector for siRNA delivery should protect siRNA from degradation, enrich siRNA in the target organ and facilitate the cellular uptake of siRNA.[27] The three main groups of siRNA nanovectors are: lipid based, non-lipid organic-based, and inorganic.[27] Lipid based nanovectors are excellent for delivering siRNA to solid tumors,[27] but other cancers may require different non-lipid based organic nanovectors such as cyclodextrin based nanoparticles.[27][32]

siRNAs delivered via lipid based nanoparticles have been shown to have therapeutic potential for central nervous system (CNS) disorders.[33] Central nervous disorders are not uncommon, but the blood brain barrier (BBB) often blocks access of potential therapeutics to the brain.[33] siRNAs that target and silence efflux proteins on the BBB surface have been shown to create an increase in BBB permeability.[33] siRNA delivered via lipid based nanoparticles is able to cross the BBB completely.[33]

A huge difficulty in siRNA delivery is the problem of off-targeting.[29][30] Since genes are read in both directions, there exists a possibility that even if the intended antisense siRNA strand is read and knocks out the target mRNA, the sense siRNA strand may target another protein involved in another function.[34]

Phase I results of the first two therapeutic RNAi trials (indicated for age-related macular degeneration, aka AMD) reported at the end of 2005 that siRNAs are well tolerated and have suitable pharmacokinetic properties.[35]

In a phase 1 clinical trial, 41 patients with advanced cancer metastasised to liver were administered RNAi delivered through lipid nanoparticles. The RNAi targeted two genes encoding key proteins in the growth of the cancer cells, vascular endothelial growth factor, (VEGF), and kinesin spindle protein (KSP). The results showed clinical benefits, with the cancer either stabilized after six months, or regression of metastasis in some of the patients. Pharmacodynamic analysis of biopsy samples from the patients revealed the presence of the RNAi constructs in the samples, proving that the molecules reached the intended target.[36][37]

Proof of concept trials have indicated that Ebola-targeted siRNAs may be effective as post-exposure prophylaxis in humans, with 100% of non-human primates surviving a lethal dose of Zaire Ebolavirus, the most lethal strain.[38]

Intracellular delivery

Delivering siRNA intracellular continues to be a challenge. There are three main techniques of delivery for siRNA that differ on efficiency and toxicity.

Transfection

In this technique siRNA first must be designed against the target gene. Once the siRNA is configured against the gene it has to be effectively delivered through a transfection protocol. Delivery is usually done by cationic liposomes, polymer nanoparticles, and lipid conjugation.[39] This method is advantageous because it can deliver siRNA to most types of cells, has high efficiency and reproducibility, and is offered commercially. The most common commercial reagents for transfection of siRNA are Lipofectamine and Neon Transfection. However it is not compatible with all cell types, and has low in vivo efficiency.[40][41]

Electroporation

Electrical pulses are also used to intracellularly deliver siRNA into cells. The cell membrane is made of phospholipids which makes it susceptible to an electric field. When quick but powerful electrical pulses are initiated the lipid molecules reorient themselves, while undergoing thermal phase transitions because of heating. This results in the making of hydrophilic pores and localized perturbations in the lipid bilayer cell membrane also causing a temporary loss of semipermeability. This allows for the escape of many intracellular contents, such as ions and metabolites as well as the simultaneous uptake of drugs, molecular probes, and nucleic acids. For cells that are difficult to transfect electroporation is advantageous however cell death is more probable under this technique.[42]

This method has been used to deliver siRNA targeting VEGF into the xenografted tumors in nude mice, which resulted in a significant suppression of tumor growth.[43]

Viral-mediated delivery

The gene silencing effects of transfected designed siRNA are generally transient, but this difficulty can be overcome through an RNAi approach. Delivering this siRNA from DNA templates can be done through several recombinant viral vectors based on retrovirus, adeno-associated virus, adenovirus, and lentivirus.[44] The latter is the most efficient virus that stably delivers siRNA to target cells as it can transduce nondividing cells as well as directly target the nucleus.[45] These specific viral vectors have been synthesized to effectively facilitate siRNA that is not viable for transfection into cells. Another aspect is that in some cases synthetic viral vectors can integrate siRNA into the cell genome which allows for stable expression of siRNA and long-term gene knockdown. This technique is advantageous because it is in vivo and effective for difficult to transfect cell. However problems arise because it can trigger antiviral responses in some cell types leading to mutagenic and immunogenic effects.

This method has potential use in gene silencing of the central nervous system for the treatment of Huntington's disease.[46]

See also

References

- Laganà, Alessandro; Veneziano, Dario; Russo, Francesco; Pulvirenti, Alfredo; Giugno, Rosalba; Croce, Carlo Maria; Ferro, Alfredo (2015). "Computational Design of Artificial RNA Molecules for Gene Regulation". RNA Bioinformatics. Methods in Molecular Biology. 1269. pp. 393–412. doi:10.1007/978-1-4939-2291-8_25. ISBN 978-1-4939-2290-1. ISSN 1064-3745. PMC 4425273. PMID 25577393.

- Bernstein E, Caudy AA, Hammond SM, Hannon GJ (January 2001). "Role for a bidentate ribonuclease in the initiation step of RNA interference". Nature. 409 (6818): 363–6. Bibcode:2001Natur.409..363B. doi:10.1038/35053110. PMID 11201747.

- Mack GS (1 June 2007). "MicroRNA gets down to business". Nature Biotechnology. 25 (6): 631–8. doi:10.1038/nbt0607-631. PMID 17557095.

- "RNA Interference (RNAi)". Retrieved 27 July 2018.

- Sharei A, Zoldan J, Adamo A, Sim WY, Cho N, Jackson E, Mao S, Schneider S, Han MJ, Lytton-Jean A, Basto PA, Jhunjhunwala S, Lee J, Heller DA, Kang JW, Hartoularos GC, Kim KS, Anderson DG, Langer R, Jensen KF (February 2013). "A vector-free microfluidic platform for intracellular delivery". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 110 (6): 2082–7. Bibcode:2013PNAS..110.2082S. doi:10.1073/pnas.1218705110. PMC 3568376. PMID 23341631.

- Daneholt, B. (2006). "Advanced Information: RNA interference". The Novel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

- Li LC (2008). "Small RNA-Mediated Gene Activation". RNA and the Regulation of Gene Expression: A Hidden Layer of Complexity. Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-25-7.

- Lee YS, Nakahara K, Pham JW, Kim K, He Z, Sontheimer EJ, Carthew RW (April 2004). "Distinct roles for Drosophila Dicer-1 and Dicer-2 in the siRNA/miRNA silencing pathways". Cell. 117 (1): 69–81. doi:10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00261-2. PMID 15066283.

- Carthew RW, Sontheimer EJ (February 2009). "Origins and Mechanisms of miRNAs and siRNAs". Cell. 136 (4): 642–55. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.035. PMC 2675692. PMID 19239886.

- Tomari Y, Zamore PD (March 2005). "Perspective: machines for RNAi". Genes & Development. 19 (5): 517–29. doi:10.1101/gad.1284105. PMID 15741316.

- Orban TI, Izaurralde E (April 2005). "Decay of mRNAs targeted by RISC requires XRN1, the Ski complex, and the exosome". RNA. 11 (4): 459–69. doi:10.1261/rna.7231505. PMC 1370735. PMID 15703439.

- Sidewski (2011). "Piwi RNA Transcripts and Their Role in Genomic Regulation". Applied Molecular Biology. 98 (36).

- Jackson, AL; Linsley, PS (January 2010). "Recognizing and avoiding siRNA off-target effects for target identification and therapeutic application". Nature Reviews. Drug Discovery. 9 (1): 57–67. doi:10.1038/nrd3010. PMID 20043028.

- Woolf, T. M.; Melton, D. A.; Jennings, C. G. (15 August 1992). "Specificity of antisense oligonucleotides in vivo". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 89 (16): 7305–7309. doi:10.1073/pnas.89.16.7305. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 49698. PMID 1380154.

- Dua, Pooja; Yoo, Jae Wook; Kim, Soyoun; Lee, Dong-ki (14 June 2011). "Modified siRNA Structure With a Single Nucleotide Bulge Overcomes Conventional siRNA-mediated Off-target Silencing". Molecular Therapy. 19 (9): 1676–1687. doi:10.1038/mt.2011.109. ISSN 1525-0016. PMC 3182346. PMID 21673662.

- Whitehead KA, Dahlman JE, Langer RS, Anderson DG (2011). "Silencing or stimulation? siRNA delivery and the immune system". Annual Review of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering. 2: 77–96. doi:10.1146/annurev-chembioeng-061010-114133. PMID 22432611. S2CID 28803811.

- Matsumiya T, Stafforini DM (2010). "Function and regulation of retinoic acid-inducible gene-I". Critical Reviews in Immunology. 30 (6): 489–513. doi:10.1615/critrevimmunol.v30.i6.10. PMC 3099591. PMID 21175414.

- Barøy, T (2010). "shRNA expression constructs designed directly from siRNA oligonucleotide sequences". Molecular Biotechnology. 45 (2): 116–20. doi:10.1007/s12033-010-9247-8. PMID 20119685.

- Birmingham A, Anderson EM, Reynolds A, Ilsley-Tyree D, Leake D, Fedorov Y, Baskerville S, Maksimova E, Robinson K, Karpilow J, Marshall WS, Khvorova A (March 2006). "3' UTR seed matches, but not overall identity, are associated with RNAi off-targets". Nature Methods. 3 (3): 199–204. doi:10.1038/nmeth854. PMID 16489337.

- Wittrup A, Lieberman J (September 2015). "Knocking down disease: a progress report on siRNA therapeutics". Nature Reviews. Genetics. 16 (9): 543–52. doi:10.1038/nrg3978. PMC 4756474. PMID 26281785.

- Khan, AA; Betel, D; Miller, ML; Sander, C; Leslie, CS; Marks, DS (June 2009). "Transfection of small RNAs globally perturbs gene regulation by endogenous microRNAs". Nature Biotechnology. 27 (6): 549–55. doi:10.1038/nbt.1543. PMC 2782465. PMID 19465925.

- Grimm, D; Streetz, KL; Jopling, CL; Storm, TA; Pandey, K; Davis, CR; Marion, P; Salazar, F; Kay, MA (25 May 2006). "Fatality in mice due to oversaturation of cellular microRNA/short hairpin RNA pathways". Nature. 441 (7092): 537–41. Bibcode:2006Natur.441..537G. doi:10.1038/nature04791. PMID 16724069.

- Dar SA, Thakur A, Qureshi A, Kumar M (January 2016). "siRNAmod: A database of experimentally validated chemically modified siRNAs". Scientific Reports. 6: 20031. Bibcode:2016NatSR...620031D. doi:10.1038/srep20031. PMC 4730238. PMID 26818131.

- Hickerson, Robyn P.; Smith, Frances J. D.; Reeves, Robert E.; Contag, Christopher H.; Leake, Devin; Leachman, Sancy A.; Milstone, Leonard M.; Irwin McLean, W. H.; Kaspar, Roger L. (1 March 2008). "Single-Nucleotide-Specific siRNA Targeting in a Dominant-Negative Skin Model". Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 128 (3): 594–605. doi:10.1038/sj.jid.5701060. ISSN 0022-202X. PMID 17914454.

- Hamilton AJ, Baulcombe DC (October 1999). "A species of small antisense RNA in posttranscriptional gene silencing in plants". Science. 286 (5441): 950–2. doi:10.1126/science.286.5441.950. PMID 10542148.

- Elbashir SM, Harborth J, Lendeckel W, Yalcin A, Weber K, Tuschl T (May 2001). "Duplexes of 21-nucleotide RNAs mediate RNA interference in cultured mammalian cells". Nature. 411 (6836): 494–8. Bibcode:2001Natur.411..494E. doi:10.1038/35078107. PMID 11373684.

- Shen H, Sun T, Ferrari M (June 2012). "Nanovector delivery of siRNA for cancer therapy". Cancer Gene Therapy. 19 (6): 367–73. doi:10.1038/cgt.2012.22. PMC 3842228. PMID 22555511.

- Alekseev OM, Richardson RT, Alekseev O, O'Rand MG (May 2009). "Analysis of gene expression profiles in HeLa cells in response to overexpression or siRNA-mediated depletion of NASP". Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology. 7: 45. doi:10.1186/1477-7827-7-45. PMC 2686705. PMID 19439102.

- Petrocca F, Lieberman J (February 2011). "Promise and challenge of RNA interference-based therapy for cancer". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 29 (6): 747–54. doi:10.1200/JCO.2009.27.6287. PMID 21079135. S2CID 15337692.

- Burnett JC, Rossi JJ (January 2012). "RNA-based therapeutics: current progress and future prospects". Chemistry & Biology. 19 (1): 60–71. doi:10.1016/j.chembiol.2011.12.008. PMC 3269031. PMID 22284355.

- Elbashir SM, Lendeckel W, Tuschl T (January 2001). "RNA interference is mediated by 21- and 22-nucleotide RNAs". Genes & Development. 15 (2): 188–200. doi:10.1101/gad.862301. PMC 312613. PMID 11157775.

- Heidel JD, Yu Z, Liu JY, Rele SM, Liang Y, Zeidan RK, Kornbrust DJ, Davis ME (April 2007). "Administration in non-human primates of escalating intravenous doses of targeted nanoparticles containing ribonucleotide reductase subunit M2 siRNA". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 104 (14): 5715–21. doi:10.1073/pnas.0701458104. PMC 1829492. PMID 17379663.

- Gomes, Dreier, Brewer et. al. A new approach for a blood-brain barrier model based on phospholipid vesicles: Membrane development and siRNA-loaded nanoparticles permability. Journal of Membrane Science. Volume 503. p.8-15. Published: March 2016.

- Shukla RS, Qin B, Cheng K (October 2014). "Peptides used in the delivery of small noncoding RNA". Molecular Pharmaceutics. 11 (10): 3395–408. doi:10.1021/mp500426r. PMC 4186677. PMID 25157701.

- Tansey B (11 August 2006). "Macular degeneration treatment interferes with RNA messages". San Francisco Chronicle.

- Vall D’Hebron Institute of Oncology (11 February 2013). "First-in-man study demonstrates the therapeutic effect of RNAi gene silencing in cancer treatment". Retrieved 31 May 2013.

- Tabernero J, Shapiro GI, LoRusso PM, Cervantes A, Schwartz GK, Weiss GJ, Paz-Ares L, Cho DC, Infante JR, Alsina M, Gounder MM, Falzone R, Harrop J, White AC, Toudjarska I, Bumcrot D, Meyers RE, Hinkle G, Svrzikapa N, Hutabarat RM, Clausen VA, Cehelsky J, Nochur SV, Gamba-Vitalo C, Vaishnaw AK, Sah DW, Gollob JA, Burris HA (April 2013). "First-in-humans trial of an RNA interference therapeutic targeting VEGF and KSP in cancer patients with liver involvement". Cancer Discovery. 3 (4): 406–17. doi:10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0429. PMID 23358650.

- Geisbert TW, Lee AC, Robbins M, Geisbert JB, Honko AN, Sood V, Johnson JC, de Jong S, Tavakoli I, Judge A, Hensley LE, Maclachlan I (May 2010). "Postexposure protection of non-human primates against a lethal Ebola virus challenge with RNA interference: a proof-of-concept study". Lancet. 375 (9729): 1896–905. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60357-1. PMC 7138079. PMID 20511019.

- Fanelli A (2016). "Transfection: In Vitro Transfection". Retrieved 5 December 2017.

- Jensen K, Anderson JA, Glass EJ (April 2014). "Comparison of small interfering RNA (siRNA) delivery into bovine monocyte-derived macrophages by transfection and electroporation". Veterinary Immunology and Immunopathology. 158 (3–4): 224–32. doi:10.1016/j.vetimm.2014.02.002. PMC 3988888. PMID 24598124.

- Chatterjea MN (2012). Textbook of Medical Biochemistry (8th ed.). New Delhi: Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers. p. 304.

- "siRNA Delivery Methods into Mammalian Cells". 13 October 2016.

- Takei Y (1 January 2014). "Electroporation-Mediated siRNA Delivery into Tumors". In Li S, Cutrera J, Heller R, Teissie J (eds.). Electroporation Protocols. Methods in Molecular Biology. 1121. Springer New York. pp. 131–138. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-9632-8_11. ISBN 9781461496311. PMID 24510818.

- Talwar GP, Hasnain S, Sarin SK (January 2016). Textbook of Biochemistry, Biotechnology, Allied and Molecular Medicine (4th ed.). PHI Learning Private Limited. p. 873. ISBN 978-81-203-5125-7.

- Morris KV, Rossi JJ (March 2006). "Lentiviral-mediated delivery of siRNAs for antiviral therapy". Gene Therapy. 13 (6): 553–8. doi:10.1038/sj.gt.3302688. PMC 7091755. PMID 16397511.

- Cambon K, Déglon N (1 January 2013). Kohwi Y, McMurray CT (eds.). Trinucleotide Repeat Protocols. Methods in Molecular Biology. 1010. Humana Press. pp. 95–109. doi:10.1007/978-1-62703-411-1_7. ISBN 9781627034104. PMID 23754221.

Further reading

- Hannon GJ, Rossi JJ (September 2004). "Unlocking the potential of the human genome with RNA interference". Nature. 431 (7006): 371–8. Bibcode:2004Natur.431..371H. doi:10.1038/nature02870. PMID 15372045.

- Endosomal entrapment of siRNA may carry therapeutic potential demonstrated an efficient release of ligand-conjugated siRNA from vesicles damaged by small molecules, enhancing target knockdown over 40 times in cancer cells DuRietz H, Hedlund H, Wilhelmson S, Nordenfelt P, Wittrup A (April 2020). "Imaging small molecule-induced endosomal escape of siRNA". Nature. 11 (1): 1809. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-15300-1. PMID 32286269.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Small interfering RNA. |