Llangolman

Llangolman (![]()

Llangolman

| |

|---|---|

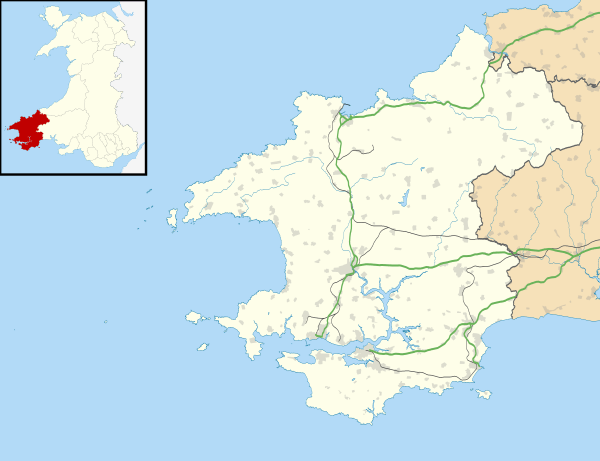

Llangolman Location within Pembrokeshire | |

| OS grid reference | SN1156826885 |

| Community | |

| Principal area | |

| Ceremonial county | |

| Country | Wales |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | LLANGOLMAN |

| Postcode district | SA66 |

| Dialling code | 01437 |

| Police | Dyfed-Powys |

| Fire | Mid and West Wales |

| Ambulance | Welsh |

| UK Parliament | |

History

Llangolman lies in a historic landscape near the upper part of the valley of the Eastern Cleddau and its tributaries. The village place name derives from the church dedicated to St. Golman, or in Irish, St Colman. Colman is attributed to Colmán of Dromore, a 6th-century saint.[1][2]

Anglican church

Llangolman church stands on high ground just to the south of the main village. The current building is Victorian or early Victorian, with little to show for the original medieval building that once stood on the site. Of historical interest is the recording in the 19th century[3] of a stone gate post about 150 yards (140 m) from the churchyard. This stone, known as the Maen-ar-Golman (the stone upon Colman) is about 7 feet (2.1 m) tall with a number of cross markings carved on the stone. The stone appears to have no inscriptions. The local belief is that Colman is buried nearby.[4]

The earliest recorded tombstone in the graveyard is for Stephen Lewis from Llangolman with the date 1778.[5]

Local chapels

There are two local chapels in the area, Llandeilo and Rhydwilym. Rhydwilym (English: William's Ford) is the oldest active Welsh Baptist chapel in the world and was founded in 1668. Funds to build the first chapel were provided by the gentleman farmer John Evans of Llwyndwr in 1701. There was a chapel on the site in 1763; a plaque on the front wall indicates that the 1763 chapel was rebuilt in 1841, and further enlarged in 1875.

The current Llandeilo chapel was built in 1882, though earlier chapel structures are recorded in the immediate vicinity. The name Llandeilo comes from the local church dedicated to the 5th-century saint, Teilo.

Historical buildings

Two gentry houses from the 18th century include Plas-y-Meibion and Llangolman Farm. There is also the house called Temple Druid (c. 1795) which was designed by John Nash, architect to King George IV, and is located roughly halfway between Llangolman and Maenclochog.

Llangolman Farm has some architectural interest.[6] Although most of the current house probably dates from the 18th century, the rear wing of the house has an older structure that includes barrel vaulting. There are two vaults, one above the other. The lower vault covers the underlying cellar which has three rooms. The end room in the cellar, and deepest, includes a fresh water well. The first room, entered from an open arched doorway, includes square holes in the vaulted ceiling that allowed butter to be easily dropped into the cellar for storage. Above the cellar vault is a second vaulted ceiling that currently houses the bathroom. The farm was a centre of production, including clay, slate, salted bacon, butter and a large mill for grinding corn.

Location and terrain

The area surrounding the village is riddled with steep wooded valleys, presumably cut during one or more of the glacial episodes of the Pleistocene. The village itself sits on a plateau where two valleys meet, the Eastern Cleddau and a tributary that originates near the small village of Llandelio. The underlying geology consists of interbedded Ordovician shales and sandstones with extensive slate outcrops. Evidence of glaciation is also seen from banks of gravel and sand to the east of the village, which form deep drainage seeps from which discharges excellent spring water.

The springs emerge in boggy land at the base of the gravel banks, where deposits of blue boulder clay, known by the natives as "indiarubber clay",[7] can also be found. Clay pits close to the farmhouses of Llangolman Farm (still visible) and Llyn are evidence that the clay was once extracted on a significant scale. The study by Jehu[7] mentions that the clay pit at Llyn was down to a depth of 15 to 20 feet, and ladders were required to get in and out. His report goes on to state that the clay is bluish in color and very tough (hence the nickname indiarubber clay). The clay covers the valley bottom from Llyn to Llangolman Farm at a level of over 400 ft.

The valley sides have largely been saved from deforestation due to their steepness, and there is some evidence of old forest along the western side of the Llandelio tributary. Otters have been seen in the rivers. Of historical interest is a surviving and working hydraulic ram that pumps water to the local farm called Ffynnon Sampson ("Sampson's Well").

Industry

The current landscape around the village is entirely rural; the local economy is mostly based on farming (dairy, cattle and sheep) and tourism (bed and breakfasts and rented cottages). Of more interest and of historical importance is the slate quarrying industry. There is a seam of green slate running roughly east–west along the Taf Valley.[8] This slate is of volcanic ash origin and of Ordovician date. The slate is generally of a greenish-grey or light blue colour.[9] This slate was often used, in addition to roofing, for covering exposed walls to keep out moisture. Until the 1970s, the outer walls of Llangolman Farm were covered in hanging slates.

The slate itself was exploited at least as early as 1860;[8] the largest quarry was Dandderwen quarry (known as Whitland Abbey Slate quarry after the name of the company which exploited it).[10] There is some suggestion that the Gilfach quarry may have been worked as early as the 16th century. It is also claimed that the slate used on the roof of the Houses of Parliament, when rebuilt in the 1830s, originated from the Gilfach quarry.[11] Much of the slate industry went into decline after the 1890s, and by the 1930s most were closed due to competition from cheaper sources. Gilfach quarry on the eastern side of the Eastern Cleddau was still in operation until 1987.[12]

There are many smaller workings dotted amongst the landscape; some of the quarries are in the steep-sided valley that carries the western tributary from Llaneilo that joins the Eastern Cleddau; some are near Llangolman Farm, with one immediately north of the farmhouse.

Schools

There are no schools in Llangolman village. Children from Llangolman would either go to Maenclochog about 2.5 miles away or until 1964 they would walk to the slightly closer school at Nant y Cwm (1.7 miles away). Nant y Cwm closed in 1964 but reopened in 1979 as a Steiner School.[13]

Archaeological sites

A number of sites at Llangolman are recorded in the 1925 Inventory of Ancient Monuments.[5]

One of the most obvious sites still visible today is the Iron Age enclosure located to the south of the village between the farms Bryn Golman and Pencraig Fawr. The site, locally called the Gear (in the field called Gear Meadow) is an enclosure that has a roughly level interior with measurements c.63m E-W and 66m N-S. The bank down-slope side stands up to 2 m high externally and 0.25 m internally. There appears to be a slight ditch on the northeast side. An entrance may be present that faces west.[14]

A second highly visible site is an enclosure called Castell Blaenllechog, located just to the west of the farm Pengawsai (itself located to the northwest of the village). It is not certain what the enclosure is, but suggestions include a medieval castle site, a medieval homestead or even an older Iron Age defensive site. What is particularly noticeable are the massive ramparts which stand 3.3 m high. Internally the height is less at about 1.5 m. Traces of a ditch 0.3 m to 0.6 m can be found to the west and south.[14] This enclosure is particularly noticeable on the aerial views from Google Maps.

References

- Baring-Gould, S (2005). The Lives of the British Saints, Vol. 2. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 0-7661-8765-9.

- Fisher, John (2005). The Lives of the British Saints, Vol. 2. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7661-8765-8.

- Lapidarium walliae: the early inscribed and sculptured stones of Wales by John Obadiah Westwood

- The lives of the British saints: the saints of Wales and Cornwall, Volume 2, Sabine Baring-Gould, John Fisher, Honourable Society of Cymmrodorion (London, England)

- An Inventory of the Ancient Monuments of Wales and Monmouthshire. VII. (Volume 7) County of Pembroke, London His Majesty's Stationery Office, 1925, The Royal Commission On The Ancient and Historical Monuments and Constructions In Wales and Monmouthshire

- "Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales - Llangolman". Retrieved 7 June 2014.

- Jehu, Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, Vol XLI, Part 1. 1906. p. 67.

- Thomas Lloyd, Julian Orbach, Robert Scourfield (2004). Pembrokeshire. Yale University Press.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Davies, David Christopher (1880). A treatise on slate and slate quarrying. Crosby Lockwood and Co.

- "Dyfed Archaeological Trust - Llangolman". Retrieved 7 June 2014.

- "Pembrokeshire Virtual Museum - Eastern Cleddau". Retrieved 7 June 2014.

- "Pembrokeshire Virtual Museum - Decline of the slate industry". Retrieved 7 June 2014.

- "Nant y Cwm Steiner School". Retrieved 7 June 2014.

- "Dyfed Archaeological Trust: A survey of defended enclosures in Pembrokeshire, 2006-7" (PDF). Retrieved 30 December 2017.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Llangolman. |