Siege of Fort Pitt

The Siege of Fort Pitt took place during June and July 1763 in what is now the city of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, United States. The siege was a part of Pontiac's War, an effort by Native Americans to remove the British from the Ohio Country and Allegheny Plateau after they refused to honor their promises and treaties to leave voluntarily after the defeat of the French. The Native American efforts of diplomacy, and by siege, to remove the British from Fort Pitt ultimately failed.

- For the 1885 action in the Canadian North-West Rebellion, see the Battle of Fort Pitt

This event is best known as an early instance of biological warfare, where the British gave items from a smallpox infirmary as gifts to Native American emissaries with the hope of spreading the deadly disease to nearby tribes. The effectiveness is unknown, although it is known that the method used is inefficient compared to respiratory transmission and these attempts to spread the disease are difficult to differentiate from epidemics occurring from previous contacts with colonists.[1][2]

Background

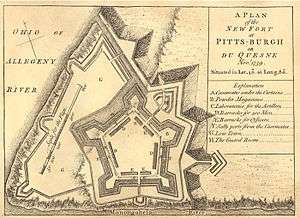

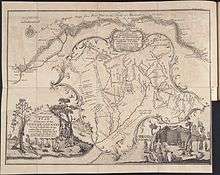

Fort Pitt was built in 1758 during the French and Indian War, on the site of what was previously Fort Duquesne in what is now the city of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, United States. The French abandoned and destroyed Fort Duquesne in November 1758 with the approach of General John Forbes's expedition. The Forbes expedition was successful in part because of the Treaty of Easton, in which area American Indians agreed to end their alliance with the French. American Indians—primarily the Six Nations, Delawares and Shawnees—made this agreement with the understanding that the British would leave the area after their war with the French. The hostilities between the French and English declined significantly after 1760, followed by a final cessation of hostilities and the formal surrender of the French at the Treaty of Paris in February 1763. Instead of leaving the territory west of the Appalachian Mountains as they had agreed, the British remained on Native lands and reinforced their forts while settlers continued to push westward.[3]

The attacks led by Pontiac against the British in early May 1763, near Fort Detroit, mark what is generally considered to be the beginning of Pontiac's War. The siege of Fort Pitt and numerous other British forts during the spring and summer of 1763 were part of an effort by American Indians to reclaim their territory by driving the British out of the Ohio Country and back across the Appalachian Mountains. While many of the forts and outposts in the region were destroyed, the Indian effort to remove the British from Fort Pitt ultimately failed.

Diplomacy and siege

By May 27, the uprising reached the tribes near Fort Pitt, and there were many signs of impending hostilities. The captain of the Fort Pitt militia learned that the Delaware tribe just north of the fort had abandoned their dwellings and cornfields overnight. The Mingo had also abandoned their villages further up the river. The proprietor of the Pennsylvania provincial store reported that numerous Delaware warriors had arrived "in fear and haste" to exchange their skins for gunpowder and lead. The western Delaware warrior leaders Wolf and Kickyuscung had fewer than 100 warriors, so did not immediately attack the well-fortified Fort Pitt. Instead, on May 29, they attacked the supporting farms, plantations and villages in the vicinity of the fort. Panicked settlers crowded into the already overcrowded fort. Captain Simeon Ecuyer tried to ready his fort after this news of expanding hostilities, putting his 230 men, half regulars and half quickly organized militia, on alert. The fort's exceptional structural defenses, made of stone with bastions covering all angles of attack, were supported by 16 cannons which he had permanently loaded. Ecuyer demolished the nearby village houses and structures to deny cover for attackers. He had trenches dug outside the fort, and set out beaver traps. Smallpox had been discovered within the fort, prompting Ecuyer to build a makeshift hospital in which to quarantine those infected.[4]

On the June 16, four Shawnee visited Fort Pitt and warned Alexander McKee and Captain Simeon Ecuyer that several Indian nations had accepted Pontiac's war belt and bloody hatchet and were going on the offensive against the British, but that the Delaware were still divided, with the older Delaware chiefs advising against war. The following day, however, the Shawnee returned and reported a more threatening situation, saying that all the nations "had taken up the hatchet" against the British, and were going to attack Fort Pitt. Even the local Shawnee themselves "were afraid to refuse" to join the uprising, a subtle hint that the occupants of Fort Pitt should leave. Ecuyer dismissed the warnings and ignored the requests to leave. On June 22, Fort Pitt was attacked on three sides by Shawnee, western Delaware, Mingo and Seneca, which prompted return fire from Ecuyer's artillery.[4] This initial attack on the fort was repelled. Since the Indians were unfamiliar with siege warfare, they opted to try diplomacy yet again. On June 24, Turtleheart spoke with McKee and Trent outside the fort, informing them that all of the other forts had fallen, and that Fort Pitt "is the only one you have left in our country." He warned McKee that "six different nations of Indians" were ready to attack if the garrison at the fort did not retreat immediately. They thanked Turtleheart and assured him that Fort Pitt could withstand "all nations of Indians", and they presented the Indian dignitaries with two small blankets and a handkerchief from the smallpox hospital.[5] For the next several days it remained relatively quiet, although reports were coming in about fort after fort falling before large bands of attacking warriors.[4]

July 3, four Ottawa newcomers requested a parley and tried to trick the occupants of Fort Pitt into surrender, but the ruse failed. This was followed by several weeks of relative quiet, through July 18 when a large group of warriors arrived, likely from the Fort Ligonier area. McKee was informed by the Shawnee that the Indians were still hopeful of an amicable outcome, similar to agreements just made at Detroit. On July 26, a large conference headed by Ecuyer was convened with several leaders of the Ohioan tribes outside the walls of Fort Pitt. The Indian delegation, Shingess, Wingenum and Grey Eyes among them, came to the fort under a flag of truce to parley, and again requested that the British leave this place. They explained that by taking the Indian's country the British caused this war, and Tessecumme of the Delaware noted that the British were the cause of the trouble since they had broken their promises and treaties. They had come onto Indian land and built forts, despite being asked not to, so now the tribes in the area have amassed to take back their lands. He informed Ecuyer that there was still a short time remaining to leave peacefully.[4][5] The Delaware and Shawnee chiefs made sure Captain Ecuyer at Fort Pitt understood the cause of the conflict. Turtleheart told him, "You marched your armies into our country, and built forts here, though we told you, again and again, that we wished you to move, this land is ours, and not yours."[6] The Delaware also let it be known, "that all the country was theirs; that they had been cheated out of it, and that they would carry on the war till they burnt Philadelphia".[4] The British refused to leave, claiming that this was their home now. They bluffed that they could hold out for three years, and bragged that several large armies were coming to their aid. This "very much enraged" the Indian delegation, Trent wrote, "White Eyes and Wingenum seemed to be very much irritated and would not shake hands with our people at parting." On July 28, the siege began in earnest and continued for several days. Seven of the fort garrison were wounded, at least one mortally; Ecuyer was wounded in the leg by an arrow.[3][7]

For Commander-in-Chief, North America Jeffery Amherst, who before the war had dismissed the possibility that the Indians would offer any effective resistance to British rule, the military situation over the summer had become increasingly grim. The frustration was so great, he wrote to Colonel Henry Bouquet and instructed him not to take any Indian prisoners. He proposed that they should be intentionally exposed to smallpox, hunted down with dogs, and "Every other method that can serve to Extirpate this Execrable Race." Amherst had directed Bouquet to take his troops to relieve Fort Pitt, a march that would take several weeks. At Fort Pitt, the siege didn't let up until August 1, 1763, when most of the Indians broke off their attack in order to intercept the body of almost 500 British troops marching to the fort under Colonel Bouquet. On August 5, these two forces met at Edge Hill in the Battle of Bushy Run. Bouquet survived the attack and the Indians were unable to prevent his command from relieving Fort Pitt on August 10.[3][7]

Aftermath

More than 500 British troops and perhaps a couple thousand settlers had died in the Ohio Valley, and of more than a dozen British forts, only Detroit, Niagara and Pitt remained standing at the height of this uprising.[6] On October 7, 1763, the Crown issued Royal Proclamation of 1763, which forbade all settlement west of the Appalachian Mountains—a proclamation ignored by British settlers, and unenforced by the British military. Fort Pitt would remain in British hands, and would become a central hub for migrant settlers as they pushed west in ever larger numbers over the next decade.

Biological warfare

Handoff of infirmary items

— William Trent, William Trent's Journal at Fort Pitt

Sometime in the spring of 1763, a smallpox epidemic broke out near Fort Pitt and subsequently spread there. A smallpox hospital was then also established there to treat sick troops.[8][9][10][11] There had also been an earlier epidemic among Ohio tribes in the early 1750s,[12][11] as smallpox outbreaks occurred every dozen or so years.[13] According to John McCullough, who was held captive, some of the Mahoning village warriors raiding a Juniata settlement caught smallpox from there that then killed some of them.[14]

In 1924 the Mississippi Valley Historical Review published a journal written by William Trent, a fur trader and merchant commissioned as a captain at Fort Pitt. For June 24, 1763, Trent wrote about a meeting with two Delaware Indians at the fort. "Out of our regard to them we gave them two Blankets and an Handkerchief out of the Small Pox Hospital. I hope it will have the desired effect."[15] The two blankets and the handkerchief from the infirmary were seemingly wrapped in a piece of linen.[16] The blankets and handkerchief were unwashed and dirty.[17] In 1955 a record of Trent's trading firm was found. It had an invoice for the handkerchief, two blankets and the linen to be given to the Natives, and the expense was signed by Ecuyer.[15] Ecuyer was relatively inexperienced, having only been a captain since April the year before and having taken over the command of the fort the same November.[17] Trent was likely the main orchestrator of the idea, considering he had more experience with the disease and had even helped out setting the smallpox hospital.[18] Half-Native Alexander McKee also played a part in parlaying messages,[19] but he possibly didn't know about the items.[17][20] This plan was carried out independently from General Amherst and Colonel Bouquet.[21][22][23][24]

The meeting happened on June 24. The night before "Two Delawares called for Mr. McKee and told him they wanted to speak to him in the Morning." The conference took place just outside of Fort Pitt. The participants were Ecuyer, McKee, Turtle's Heart, and another Delaware, "Mamaltee a Chief." The two Delaware men tried to coax the people holed up in the fort to leave, an option that Ecuyer promptly rejected and stated that reinforcements were coming to Fort Pitt and that the stronghold could easily hold out. After conferring with their chiefs, the two "returned and said they would hold fast of the Chain of friendship", but they were not genuinely believable. The messengers had asked for presents such as food and alcohol, "to carry us Home." Requesting gifts was common, but Ecuyer in this case seemed especially generous. Turtle's Heart and his companion received food in "large quantities", some "600 Rations." Included among this was the linen bundle containing the handkerchief and two blankets.[25]

Levy, Trent and Company: Account against the Crown, Aug. 13, 1763[26]

2 Blankets @ 20/ £2" 0" 0

1 Silk Handkerchef 10/

A month after meeting on July 22, Trent met with the same delegates again and they seemingly had not contracted smallpox: "Gray Eyes, Wingenum, Turtle's Heart and Mamaultee, came over the River told us their Chiefs were in Council, that they waited for Custaluga who they expected that Day."[27][16]

Gershom Hicks, who was fluent in the Delaware language and also knew some Shawnee, testified that starting from spring 1763 up to April 1764 around a hundred Natives from different tribes such as Lenni Lenape (Delaware) and Shawnee died in the smallpox epidemic, making it a relatively minor smallpox outbreak.[11][28] After visiting Pittsburgh a few years later, David McClure would write in his journal published in 1899, "I was informed at Pittsburgh, that when the Delawares, Shawanese & others, laid siege suddenly and most traitorously to Fort Pitt, in 1764, in a time of peace, the people within, found means of conveying the small pox to them, which was far more destructive than the guns from the walls, or all the artillery of Colonel Boquet's army, which obliged them to abandon the enterprise."[29]

Amherst letters

Colonel Bouquet, July 13: P.S. I will try to inocculate the Indians by means of Blankets that may fall in their hands, taking care however not to get the disease myself.

Amherst, July 16: P.S. You will Do well to try to Innoculate the Indians by means of Blanketts, as well as to try Every other method that can serve to Extirpate this Execreble Race.

Bouquet, July 19: The signal for Indian Messengers, and all your Directions will be observed.

— Papers of Col. Henry Bouquet, ed. Stevens and Kent, ser. 21634, p. 161.

A month later in July Colonet Bouquet discussed Pontiac's War in detail with General Amherst via letters,[30] and in postscripts of three letters in more freeform style Amherst also briefly broached the subject of using of smallpox as a weapon. Bouquet brought up blankets as a means without going into specifics, and Amherst supported the idea "to Extirpate this Execreble Race".[10][31]

Bouquet himself probably never had the opportunity to "Send the Small Pox."[22] He was very concerned about smallpox, having never had it.[32] When Bouquet wrote to Ecuyer, he didn’t mention the disease.[21] He died only two years later in 1765 of yellow fever.[32]

Later assessments

This event is usually described as an early attempt at biological warfare.[33][34][35][36] However the plan’s effectiveness is generally questioned.[33][1][2][16][14]

Early research

The account of the British infecting Natives with smallpox during Pontiac's War of 1763 originated with nineteenth century historian Francis Parkman.[12] His account has been relied on by later writers.[23][15] He described Amherst’s reply to Bouquet as a “detestable suggestion” and concluded "There is no direct evidence that Bouquet carried into effect the shameful plan of infecting the Indians though, a few months after, the small-pox was known to have made havoc among the tribes of the Ohio."[23] Parkman had the impression that Amherst had planned the gifting, although Amherst approached the matter only a month later.[24][23] Following Parkman was Howard Peckham who was more interested in the overall war and paid only cursory glance to the incident, briefly describing Ecuyer handing over the handkerchief and blankets from the smallpox hospital. He quoted a testimony of a smallpox outbreak and stated that it certainly affected the Natives' ability to wage war.[37] Bernhard Knollenberg was more critical and pointed out that both Parkman and Peckham hadn't noticed that the smallpox epidemic among the tribes had been reported to have begun in the spring of 1763, quite some time before the meeting.[38][11][9] Knollenberg even doubted the authenticity of the documents at first before he was contacted via letter by historian Donald H. Kent who had found a record of Trent's sundries list signed by Ecuyer.[11]

Later researchers

Francis Jennings, a historian who extensively studied Parkman's writings, had a more damning view. He indicated that the fighting strength of the Natives was greatly compromised by the plan.[39] Microbiologist Mark Wheelis says the act of biological aggression at Fort Pitt is indisputable, but that at the time the rare attempts to transmit infection rarely worked and they were probably made redundant with natural routes of transmission. The practice was restrained by lack of knowledge.[40] Elizabeth A. Fenn writes that "the actual effectiveness of an attempt to spread smallpox remains impossible to ascertain: the possibility always exists that infection occurred by some natural route."[33] Philip Ranlet describes as a clear sign that the blankets had no effect the fact that the same delegates were met a month later,[16] and that nearly all of the met natives were recorded to have lived for decades afterwards.[41] He also questions why Trent didn't gloat about any possible success in his journal if there was such.[16] David Dixon holds likely that the transmission happened via some other route and possibly from the event described by John McCullough.[14] Barbara Mann holds that the distribution worked, describing that Gershom Hick's testimony of the epidemic starting by spring is explainable by Hicks lacking a calendar.[42] Mann also estimates that papers related to the incident have been destroyed.[43]

Researchers James W. Martin, George W. Christopher and Edward M. Eitzen writing in a publication for the US Army Medical Department Center & School, Borden Institute, found that "In retrospect, it is difficult to evaluate the tactical success of Captain Ecuyer's biological attack because smallpox may have been transmitted after other contacts with colonists, as had previously happened in New England and the South. Although scabs from smallpox patients are thought to be of low infectivity as a result of binding of the virus in fibrin metric, and transmission by fomites has been considered inefficient compared with respiratory droplet transmission."[2] In an article published in the journal Clinical Microbiology and Infection researchers Vincent Barras and Gilbert Greub conclude that “in the light of contemporary knowledge, it remains doubtful whether his hopes were fulfilled, given the fact that the transmission of smallpox through this kind of vector is much less efficient than respiratory transmission, and that Native Americans had been in contact with smallpox >200 years before Ecuyer’s trickery, notably during Pizarro’s conquest of South America in the 16th century. As a whole, the analysis of the various ‘pre-microbiological” attempts at BW illustrate the difficulty of differentiating attempted biological attack from naturally occurring epidemics.”[1]

Citations

- Barras 2014.

- Martin 2007, p. 3.

- Sipe 1931.

- Middleton 2008.

- Harpster 1938, pp. 103-104.

- Calloway 2006.

- Dowd 2002.

- Trevor 2016, p. 117.

- Fenn 2000, p. 1557.

- Knollenberg 1954, p. 6.

- Ranlet 2000, p. 9.

- Parkman 1851.

- King 2016, p. 73.

- Dixon 2005, p. 155.

- Ranlet 2000, p. 2.

- Ranlet 2000, p. 8.

- Ranlet 2000, p. 10.

- Ranlet 2000, p. 11.

- Mann 2009, pp. 8, 10.

- Mann 2009, p. 13.

- Ranlet 2000, p. 3.

- Ostler 2019, p. 60.

- Knollenberg 1954, p. 2.

- Mann 2009, pp. 8-9.

- Ranlet 2000, pp. 7-8.

- Fenn 2000, p. 1554.

- Dixon 2005, p. 154.

- White 2011, p. 44.

- Dexter 1899, pp. 92-93.

- King 2016, p. 72.

- McConnell 1992.

- Ranlet 2000, p. 5.

- Fenn 2000, p. 1564.

- http://metro.co.uk/2013/04/08/could-smallpox-really-be-turned-into-a-biological-weapon-by-terrorists-3585028/

- Riedel 2004.

- http://www.kliinikum.ee/infektsioonikontrolliteenistus/doc/oppematerjalid/Referaadid/Rouged.pdf

- Peckham 1947.

- Knollenberg 1954.

- Jennings 1988.

- Wheelis 1999, p. 33.

- Ranlet 2000, p. 12.

- Mann 2009, p. 18.

- Mann 2009, p. 9.

References

- Barras, V.; Greub, G. (June 2014). "History of biological warfare and bioterrorism". Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 20 (6): 497–502. doi:10.1111/1469-0691.12706. PMID 24894605.

- Calloway, Colin G. (2006). The Scratch of a Pen: 1763 and the Transformation of North America. Oxford University Press. pp. 66–75.

- Dexter, Franklin B. (1899). Diary of David McClure, Doctor of Divinity, 1748–1820.

- Dowd, Gregory Evans (2002). War Under Heaven: Pontiac, the Indian Nations, & the British Empire. Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 144–7, 190. ISBN 0-8018-7079-8.

- Dixon, David (2005). Never Come to Peace Again: Pontiac's Uprising and the Fate of the British Empire in North America. University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 152–155. ISBN 9780806136561.

- Fenn, Elizabeth A. (March 2000). "Biological Warfare in Eighteenth-Century North America: Beyond Jeffery Amherst". The Journal of American History. 86 (4): 1552–1580. doi:10.2307/2567577. JSTOR 2567577.

- Harpster, John W. (1938). "Fort Pitt holds out". Pen Pictures of Early Western Pennsylvania. University of Pittsburgh Press.

- Jennings, Francis (1988). Empire of Fortune: Crowns, Colonies, and Tribes in the Seven Years War in America. Norton. ISBN 9780393025378.

- King, J. C. H. (2016). Blood and Land: The Story of Native North America. Penguin UK. ISBN 9781846148088.

- Knollenberg, Bernhard (December 1954). "General Amherst and Germ Warfare". The Mississippi Valley Historical Review. 41 (3): 489–494. doi:10.2307/1897495. JSTOR 1897495.

- Mann, Barbara Alice (2009). The Tainted Gift: The Disease Method of Frontier Expansion. Praeger. ISBN 9780313353383.

- Martin, James W.; Christopher, George W.; Eitzen, Edward M. (2007). "History of biological weapons: From poisoned darts to intentional epidemics". Medical Aspects of Biological Warfare. Government Printing Office. p. 3. ISBN 9780160872389.

- McConnell, Michael N. (1992). A Country Between: The Upper Ohio Valley and Its Peoples, 1724-1774. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 9780803231429.

- Middleton, Richard (2007). Pontiac's War: Its Causes, Course and Consequences. Routledge. pp. 83–91.

- Ostler, Jeffrey (2019). Surviving Genocide: Native Nations and the United States from the American Revolution to Bleeding Kansas. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300245264.

- Parkman, Francis (1851). The Conspiracy of Pontiac and the Indian War after the Conquest of Canada.

- Peckham, Howard H. (1947). Pontiac and the Indian Uprising.

- Ranlet, P (2000). "The British, the Indians, and smallpox: what actually happened at Fort Pitt in 1763?". Pennsylvania History. 67 (3): 427–41. PMID 17216901.

- Riedel, S (October 2004). "Biological warfare and bioterrorism: a historical review". Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 17 (4): 400–6. doi:10.1080/08998280.2004.11928002. PMC 1200679. PMID 16200127.

- Royle, Trevor (2016). Culloden: Scotland's Last Battle and the Forging of the British Empire. Hachette UK. ISBN 9781405514767.

- Sipe, C.H. (1931). The Indian wars of Pennsylvania. pp. 407–424.

- Wheelis, Mark (1999). "Biological warfare before 1914". In Geissler, E.; Moon, J. (eds.). Biological and Toxin Weapons: Research, Development and Use from the Middle Ages to 1945. Oxford University Press. pp. 8–34.

- Phillip M. White (June 2, 2011). American Indian Chronology: Chronologies of the American Mosaic. Greenwood Publishing Group.

External links

- NativeWeb documents on: Amherst-Bouquet - Fort Pitt - Fenn on smallpox in the Americas

- Bouquet Papers

- Global Biosecurity: Threats and Responses; Katona, Peter; Routledge

- Ecuyer, Simeon: Fort Pitt and letters from the frontier (1892): Entry June 2, 1763 - Entry of June 24, 1763

- "Colonial Germ Warfare", article from Colonial Williamsburg Journal

- John McCullough Narrative

- History of that part of the Susquehanna and Juniata valleys, embraced in the counties of Mifflin, Juniata, Perry, Union and Snyder, in the commonwealth of Pennsylvania; Everts, Peck & Richards; 1886

- Pioneers of Second Fork James P. Burke

- Proceedings of Sir William Johnson with the Indians at Fort Stanwix to settle a Boundary Line. 1768