Battle of Fort Pitt

The Battle of Fort Pitt (in Saskatchewan) was part of a Cree uprising coinciding with the Métis revolt that started the North-West Rebellion in 1885. Cree warriors began attacking Canadian settlements on April 2. On April 15, they captured Fort Pitt from a detachment of North-West Mounted Police.

| Battle of Fort Pitt | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the North-West Rebellion | |||||||

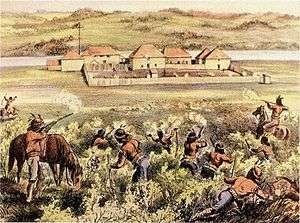

This contemporary illustration from The Illustrated London News depicts the Cree attack of April 15 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Cree |

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Big Bear | Francis Dickens | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 200-250[1][2] | 22 militia[2] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 0-4 dead[1][2] |

1 dead[1] 1 wounded[1] | ||||||

Background

In the Canadian North-West, a period of escalating unrest immediately preceded the rebellion as Ottawa refused to negotiate with its disaffected citizens. While the Métis under Louis Riel declared a provisional government and mobilized their forces, Cree chief Big Bear was not planning any militarization or violence toward the Canadian settlers or government. Rather, he had tried to unify the Cree into a political confederacy powerful enough to oppose the marginalization of native people in Canadian society and renegotiate unjust land treaties imposed on Saskatchewan natives in the 1860s.

This nominally peaceful disposition was shattered in late March by news of the Métis victory over government forces at Duck Lake. Support for Riel was strong among native peoples. On April 2, Big Bear's warriors attacked the town of Frog Lake, killing nine civilians. Big Bear, against his wishes, was drawn into the rebellion.

Similar attacks continued, with Cree raiding parties pillaging the towns of Lac La Biche[3] Saddle Lake, Beaverhill Lake, Bear Hills, Lac St. Anne and Green Lake.[4] These events prompted the mobilization of an Alberta field force under Thomas Bland Strange. The Cree would later defeat the Albertans at the Battle of Frenchman's Butte.

Battle

On April 15, 200 Cree warriors descended on Fort Pitt. They intercepted a police scouting party, killing a constable, wounding another, and captured a third. Surrounded and outnumbered, garrison commander Francis Dickens (son of famed novelist Charles Dickens) capitulated and agreed to negotiate with the attackers. Big Bear released the remaining police officers but kept the townspeople as hostages and destroyed the fort. Six days later, Inspector Dickens and his men reached safety at Battleford.[1][2]

Legacy

In the spring of 2008, Tourism, Parks, Culture and Sport Minister Christine Tell proclaimed in Duck lake, that "the 125th commemoration, in 2010, of the 1885 Northwest Resistance is an excellent opportunity to tell the story of the prairie Métis and First Nations peoples' struggle with Government forces and how it has shaped Canada today."[5] Fort Pitt, the scene of the Battle of Fort Pitt, is a Provincial Park and National Historic site where a National Historic Sites and Monuments plaque designates where Treaty six was signed.[6][7][8]

See also

- List of battles won by Indigenous peoples of the Americas

References

- William Bleasdell Cameron (1888), The war trail of Big Bear (The Fall of Fort Pitt), Toronto: Ryerson Press (published 1926)

- "The Illustrated War News, 02 May 1885, Page 7, Item Ar00701". J.W. Bengough. Toronto: Grip Print. and Pub. Co. 1885-05-02. p. 7. Retrieved 2013-11-24.

- Heather Devine (2004). The People who Own Themselves: Aboriginal Ethnogenesis in a Canadian Family, 1660-1900. University of Calgary Press. p. 162. ISBN 978-1-55238-115-1.

- "Batoche: les missionnaires du nord-ouest pendant les troubles de 1885". Le Chevallier, Jules Jean Marie Joseph. Montreal: L'Oeuvre de presse dominicaine. 1941. Retrieved 2013-07-20.

- "Tourism agencies to celebrate the 125th anniversary of the Northwest Resistance/Rebellion". Home/About Government/News Releases/June 2008. Government of Saskatchewan. June 7, 2008. Archived from the original on 21 October 2009. Retrieved 2009-09-20.

- "Fort Pitt Provincial Park - Tourism, Parks, Culture and Sport -". Government of Saskatchewan. Archived from the original on 2009-04-15. Retrieved 2009-09-20.

- "Fort Pitt brochure Fort Pitt and the 1885 Resistance/Rebellion". Government of Saskatchewan. Archived from the original on 2009-04-16. Retrieved 2009-09-20.

- Beal, Bob (1 Sep 2007). "Fort Pitt". Historica-Dominion. The Canadian Encyclopedia Historica foundation. Archived from the original on 2011-06-07. Retrieved 2009-09-20.