Bab Sharqi

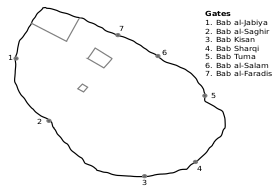

Bab Sharqi (Arabic: باب شرقي; "The Eastern Gate"), also known as the Gate of the Sun, is one of the seven ancient city gates of Damascus, Syria. Its modern name comes from its location in the eastern side of the city. The gate also gives its name to the Christian quarter surrounding it. The grand facade of the gate was reconstructed in the 1960s.[1]

| Bab Sharqi | |

|---|---|

باب شرقي | |

Bab Sharqi at the end of Street Called Straight | |

| |

| Alternative names | Gate of the Sun |

| General information | |

| Type | City gate |

| Location | Damascus, Syria |

| Completed | ca. 200 AD |

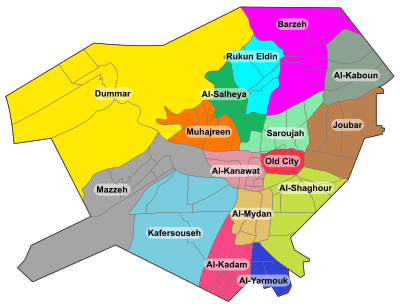

| Old City of Damascus |

|---|

| Location of the Mosque in Relation to the Citadel and the Ázm Palace |

In addition to being the only original Roman gate still standing, Bab Sharqi is also the only gate of the eight gates of the Ancient City of Damascus to preserve its original form as a triple passageway, with the large central passageway for caravans and wheel traffic and the two smaller ones flanking the large one for pedestrians.[2]

History

The gate, which was dedicated to the sun by the Romans and known to them as the Gate of The Sun, dates back to ca. 200 AD.[3] Although the gate had little defensive structures in the Roman period, it was most likely flanked by towers from both sides. Its architecture was minimal with the only adoration being the tall pilasters projecting from its walls. The gate, 26 metres (85 ft) wide, stood over a grand avenue, the city's Decumanus Maximus known by biblical sources as the Street Called Straight, which was to become the main artery in the city. The avenue included a central carriageway for wheeled vehicles 14 metres (46 ft) wide, and two pedestrian arcaded pavements. Remains of the cross-city colonnade survive inside the gate.[1] The Street Called Straight, still connects the eastern gate of the city to the western gate, or Bab al-Jabiyah.[3]

Damascus was conquered by Muslims during the Rashidun era. Following the capture of Damascus by Khalid ibn al-Walid's army, he entered through this gate on 18 September 634.[4] His granting of Christian citizens continued access to their churches in the eastern district started the gradual evolution of the city's Christian Quarter near the gate.[2]

In the 12th-century during the reign of Nur ad-Din Zangi, the gate was partially blocked except for the central opening which was converted into a bent entrance. A minaret was also added on top of the gate.[5]

References

- Burns, Ross (2005). Damascus: A History. Routledge. pp. 55–56. ISBN 0-415-27105-3.

- Diana, Darke (2010). Syria. Bradt Travel Guides. p. 108. ISBN 9781841623146.

- Wallace, Richard; Williams, Wynne (1998). The Three Worlds of Paul of Tarsus. Routledge. p. 163. ISBN 0-415-13592-3.

- Burns, Ross (2005). Damascus: A History. Routledge. p. 99. ISBN 0-415-27105-3.

- Tabbaa, Yasser (1997). Constructions of Power and Piety in Medieval Aleppo. Penn State Press. p. 68. ISBN 0-271-01562-4.