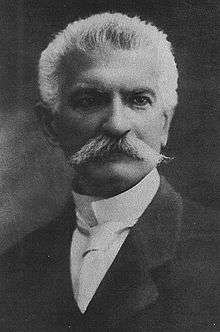

Sidney Sonnino

Sidney Costantino, Baron Sonnino (11 March 1847 – 24 November 1922) was an Italian statesman, 19th Prime Minister of Italy and twice served briefly as one, in 1906 and again from 1909 to 1910.[1] He also was the Italian Minister of Foreign Affairs during the First World War, representing Italy at the 1919 Paris Peace Conference.

Sidney Sonnino | |

|---|---|

| |

| 19th Prime Minister of Italy | |

| In office 11 December 1909 – 31 March 1910 | |

| Monarch | Victor Emmanuel III |

| Preceded by | Giovanni Giolitti |

| Succeeded by | Luigi Luzzatti |

| In office 8 February 1906 – 29 May 1906 | |

| Preceded by | Alessandro Fortis |

| Succeeded by | Giovanni Giolitti |

| Minister of the Treasury[1] | |

| In office 3 January 1889 – 9 March 1889 | |

| Prime Minister | Francesco Crispi |

| Preceded by | Bonaventura Gerardi |

| Succeeded by | Giovanni Giolitti |

| In office 15 December 1893 – 10 March 1896 | |

| Prime Minister | Francesco Crispi |

| Preceded by | Bernardino Grimaldi |

| Succeeded by | Giuseppe Colombo |

| Minister of Finance[1] | |

| In office 15 December 1893 – 14 June 1894 | |

| Prime Minister | Francesco Crispi |

| Preceded by | Lazzaro Gagliardo |

| Succeeded by | Paolo Boselli |

| Minister of Foreign Affairs[1] | |

| In office 5 November 1914 – 23 June 1919 | |

| Prime Minister | Antonio Salandra Paolo Boselli Vittorio Emanuele Orlando |

| Preceded by | Antonino Paternò Castello |

| Succeeded by | Tommaso Tittoni |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 11 March 1847 Pisa, Tuscany |

| Died | 24 November 1922 (aged 75) Rome, Italy |

| Political party | Historical Right (1880–1882) Constitutional[2][3] (1882–1913) Liberal Union (1913–1922) |

| Alma mater | University of Pisa |

| Profession | |

Biography

Early life

Sonnino was born in Pisa to an Italian father of Jewish heritage (Isacco Saul Sonnino, who converted to Anglicanism) and a Welsh mother, Georgina Sophia Arnaud Dudley Menhennet. He was raised an Anglican by his family.[4][5] His grandfather had emigrated from the ghetto in Leghorn to Egypt where he had built up an enormous fortune as a banker.[6]

After graduating in law in Pisa in 1865, Sonnino became a diplomat and an official at the Italian embassies in Madrid, Vienna, Berlin and Paris, from 1866 until 1871.[4] His family lived at the Castello Sonnino in Quercianella, near Leghorn. He retired from the diplomatic service in 1873.

In 1876, Sonnino traveled to Sicily with Leopoldo Franchetti to conduct a private investigation into the state of Sicilian society. In 1877, the two men published their research on Sicily in a substantial two-part report for the Italian Parliament. In the first part Sonnino analysed the lives of the island's landless peasants. Leopoldo Franchetti's half of the report, Political and Administrative Conditions in Sicily, was an analysis of the Mafia in the nineteenth century that is still considered authoritative today. Franchetti would ultimately influence public opinion about the Mafia more than anyone else until Giovanni Falcone over a hundred years later. Political and Administrative Conditions in Sicily is the first convincing explanation of how the Mafia came to be.[7]

In 1878, Sonnino and Franchetti started a newspaper (La Rassegna Settimanale), which changed from weekly economic reviews to daily political issues.[4]

Political career

Sonnino was elected in the Italian Chamber of Deputies for the first time in the general elections in May 1880, from the constituency of San Casciano in Val di Pesa. He belonged to the chamber to September 1919 from the XIV to XXIV legislature. He supported universal suffrage.[8] Sonnino soon became one of the leading opponents of the Liberal Left. As a strict constitutionalist he favoured strong government to resist pressure of special interests, making him a conservative liberal.[9]

In December 1893, he became Minister of Finance (December 1893 – June 1894) and Minister of the Treasury (December 1893 – March 1896) in the government of Francesco Crispi, and tried to resolve the Banca Romana scandal. Sonnino envisaged to establish a single bank of issue, but the main priority of his bank reform was to rapidly solve the financial problems of the Banca Romana, as well as to cover up the scandal which involved the political class, rather than to design a new national banking system. The newly established Banca d'Italia was the result of a merger of three existing banks of issue (the Banca Nazionale and two banks from Tuscany). Regional interests were still strong; hence the compromise of plurality of note issuance with the Banco di Napoli and the Banco di Sicilia, while providing for stricter state control.[10][11][12]

As Minister of the Treasury Sonnino restructured public finances, imposing new taxes[13] and cutting public spending. The budget deficit was sharply reduced, from 174 million lire in 1893–94 to 36 million in 1896–97.[14] After the fall of the Crispi government as a result of the lost Battle of Adwa in March 1896, he served as the leader of the opposition conservatives against the liberal Giovanni Giolitti. In January 1897, Sonnino published an article titled Torniamo allo Statuto (Let's go back to the Statute), in which he sounded the alarm about the threats that the clergy, republicans and socialists posed to liberalism. He called for the abolition of the system of parliamentary governments and the return of the royal prerogative to appoint and dismiss the Prime Minister without consulting parliament, as the only possible way to avert the danger.[4][9][15] In 1901 he founded a new major newspaper, Il Giornale d'Italia.[4]

Opposition and Prime Minister

In response the social reforms presented by the Prime Minister Giuseppe Zanardelli in November 1902,[16] Sonnino introduced a reform bill to alleviate poverty in southern Italy. The bill provided for a reduction of the land tax in Sicily, Calabria and Sardinia, the facilitation of agricultural credit, the re-establishment of the system of perpetual lease for small holdings (emphyteusis) dissemination and enhancement of agrarian contracts in order to combine the interests of farmers with those of the land-owners.[17] Sonnino criticised the usual approach to solve the crisis through public works: "to construct railways where there is no trade is like giving a spoon to a man who has nothing to eat."[18]

Sonnino's uncompromising severity towards others proved to be an obstacle to form his own government for a long time.[6] Nevertheless, Sonnino served twice briefly as Prime Minister. On 8 February 1906 Sonnino formed his first government,[19] which lasted only three months; on 18 May 1906,[20] after a mere 100 days, he was forced to resign.[4] He proposed major changes to transform Southern Italy, which provoked opposition from the ruling groups. Land taxes were to be reduced by one-third, except for the really big landowners. He also proposed the establishment of provincial banks and to subsidize schools.[21] His reforms provoked opposition from the ruling groups. He was succeeded by Giovanni Giolitti.

On 11 December 1909 Sonnino formed his second government, with a strong connotation to the centre-right, but it did not last much longer, falling on 21 March 1910.[4]

First World War

After the events in 1914, Sonnino was initially supportive to the side of the old allies of the Triple Alliance, Germany and Austria-Hungary. He firmly believed that Italian self-interest entailed participation in the war, with its prospect of Italian territorial gains as a completion of Italian unification.[22] However, after becoming Minister of Foreign Affairs in November 1914 in the conservative government of Antonio Salandra and realizing that it was unlikely to secure Austro-Hungarian agreement to the concession of certain Austro-Hungarian territories to Italy, he sided with the Entente powers – France, Great Britain and Russia – and sanctioned the secret Treaty of London in April 1915 to fulfill Italy’s irrendentist claims. Italy consequently declared war on Austria-Hungary on May 23, 1915.[22][23]

He remained Minister of Foreign Affairs in three consecutive governments and represented Italy at the 1919 Paris Peace Conference with Prime Minister Vittorio Emanuele Orlando. Sonnino defended the literal application of the Treaty of London and opposed to a policy of nationalities in the former territories of the Habsburg Empire.[22][24] Orlando's inability to speak English and his weak political position at home allowed Sonnino to play a dominant role. Their differences proved to be disastrous during the negotiations. Orlando was prepared to renounce territorial claims for Dalmatia to annex Rijeka (or Fiume as the Italians called the town) – a major seaport on the Adriatic Sea – while Sonnino was not prepared to give up Dalmatia. Italy ended up claiming both and got none, due to strong opposition to Italian demands by U.S. President Woodrow Wilson and his policy of national self-determination.[23][24]

End of career and legacy

When the territorial ambitions of Italy towards Austria-Hungary had to be substantially reduced, Orlando’s government resigned in June 1919. It was the end of Sonnino's political career and he did not participate in the elections in November 1919. Nominated senator in October 1920, he did not actively participate. Sonnino died suddenly on 24 November 1922 in Rome, suffering an apoplectic stroke.[4][6] Known as the "silent statesman of Italy", he could speak five languages fluently.[6] One of Sonnino's main aims was to revive southern Italy economically and morally, as well as to fight illiteracy.[6] He never married.[6]

The only Protestant leader in Italian politics, Sonnino was described as "decidedly British in manner and thought" and "the great puritan of the Chamber, the last uncorrupted man". His stern intransigent moralism made him a difficult man and, although his integrity was universally respected, his closed and taciturn personality gained him few friends in political circles.[25]

A New York Times obituary described Sonnino as an intellectual aristocrat, great financier and an accomplished scholar with little talent for popularity whose greatness would have been unmistakable in the days of absolute monarchy. He was further portrayed as a very able diplomat belonging to the "old" diplomacy with an undeserved prominence at the Paris Peace Conference as the typical imperialistic annexationist at a time when the diplomatic rules had been changed.[26] According to historian R.J.B. Bosworth, "Sidney Sonnino, who was Foreign Minister from 1914 to 1919, and with a personal reputation, perhaps deserved, for honesty in all his dealings, has strong claims to have conducted Italy’s least successful foreign policy."[27]

Trivia

On 16 April 1909 Wilbur Wright took Sonnino on a flight at Centocelle field, Rome, making Sonnino one of the earliest of statesmen to fly in an airplane.[28]

List of Sonnino's cabinets

1st cabinet (8 February – 29 May 1906)

| Portfolio | Holder | Party | |

|---|---|---|---|

| President of the Council of Ministers | Sidney Sonnino | Conservative | |

| Ministers | |||

| Minister of the Interior | Sidney Sonnino | Conservative | |

| Minister of Foreign Affairs | Francesco Guicciardini | Democrat | |

| Minister of Finance | Antonio Salandra | Conservative | |

| Minister of Treasury | Luigi Luzzatti | Conservative | |

| Minister of Justice and Worship | Ettore Sacchi | Radical | |

| Minister of War | Lt. General Luigi Majnoni d'Intignano | Military | |

| Minister of the Navy | Admiral Carlo Mirabello | Military | |

| Minister of Public Education | Paolo Boselli | Conservative | |

| Minister of Public Works | Pietro Carmine | Conservative | |

| Minister of Post and Telegraph | Alfredo Baccelli | Democrat | |

| Minister of Agricolture, Industry and Commerce | Edoardo Pantano | Democrat | |

2nd cabinet (11 December 1909 – 31 March 1910)

| Portfolio | Holder | Party | |

|---|---|---|---|

| President of the Council of Ministers | Sidney Sonnino | Conservative | |

| Ministers | |||

| Minister of the Interior | Sidney Sonnino | Conservative | |

| Minister of Foreign Affairs | Francesco Guicciardini | Democrat | |

| Minister of Finance | Enrico Arlotta | Conservative | |

| Minister of Treasury | Antonio Salandra | Conservative | |

| Minister of Justice and Worship | Vittorio Scialoja | None | |

| Minister of War | Lt. General Paolo Spingardi | Democrat | |

| Minister of the Navy | Admiral Giovanni Bettolo | Conservative | |

| Minister of Public Education | Edoardo Daneo | Conservative | |

| Minister of Public Works | Giulio Rubini | Democrat | |

| Minister of Post and Telegraph | Ugo di Sant'Onofrio del Castillo | Conservative | |

| Minister of Agricolture, Industry and Commerce | Luigi Luzzatti | Conservative | |

References

- (in Italian) Sidney Sonnino, Incarichi di governo, Parlamento italiano (Accessed May 8, 2016)

- Emanuela Minuto (2004). "Il partito dei parlamentari. Sidney Sonnino e le istituzioni rappresentative (1900–1906)". SISSCO.

- Salvatore Sechi. "Sonnino e il Partito Liberale di massa". Critica Sociale.

- (in Italian) Sidney Sonnino (1847–1922). Note biografiche, Centro Studi Sidney Sonnino

- Morley Sachar, A History of the Jews in the Modern World, p. 541

- Baron Sonnino Dies; Italy's Ex-Premier; Foreign Minister During the Great War Stricken Suddenly With Apoplexy, The New York Times, November 24, 1922

- Dickie, Cosa Nostra, p. 43-54

- (in Italian) Sidney Costantino Sonnino, Camera dei diputati, portale storico

- Sarti, Italy: a reference guide from the Renaissance to the present, p. 567

- Seton-Watson, Italy from liberalism to fascism, pp. 154–56

- Alfredo Gigliobianco and Claire Giordano, Economic Theory and Banking Regulation: The Italian Case (1861-1930s) Archived 2012-03-27 at the Wayback Machine, Quaderni di Storia Economica (Economic History Working Papers), Nr. 5, November 2010

- Pohl & Freitag, Handbook on the history of European banks, p. 564

- Increased Taxation In Italy; Chamber of Deputies Approves the Scheme Outlined by Sonnino, The New York Times, December 11, 1894

- Clark, Modern Italy: 1871 to the present, p. 147

- Clark, Modern Italy: 1871 to the present, p. 140

- Proposed Reforms In Italy; Government Formulates Its Social Programme, The New York Times, November 15, 1902

- Notes of "The Observer" in Rome; Why Baron Sonnino's Reform is Purely a Charity Measure, The New York Times, November 23, 1902

- Wretchedness In Italy; People Suffering Dire Distress – "The Only Thing Which Prospers," Says Sonnino, "is the Blood-Sucking Octopus of Usury", The New York Times, February 5, 1903

- New Italian Cabinet; Baron Sonnino Premier and Count Guicciardini Foreign Minister, The New York Times, February 9, 1906

- Italian Cabinet Resigns; Thursday's Vote Showed Unexpected Strength In the Opposition, The New York Times, May 19, 1906

- Clark, Modern Italy: 1871 to the present, p. 160

- Who's Who – Sidney Sonnino at firstworldwar.com

- MacMillan, Paris 1919, pp. 283–92

- Burgwyn, Italian Foreign Policy in the Interwar Period, 1918–1940, p. 12-14

- Rossini, Woodrow Wilson and the American Myth in Italy, p. 164

- Sonnino, The New York Times, November 25, 1922

- Bosworth, Italy and the Wider World, p. 39

- Wright Flies In Italy; Takes Up Italian Army Officer in His Aeroplane and Later Signor Sonnino, The New York Times, April 17, 1909

- Bosworth, R.J.B. (2013). Italy and the Wider World: 1860–1960, New York: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-13477-3

- Burgwyn, H. James (1997). Italian Foreign Policy in the Interwar Period, 1918–1940, Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 0-275-94877-3

- Clark, Martin (2008). Modern Italy: 1871 to the present, Harlow: Pearson Education, ISBN 1-4058-2352-6

- Dickie, John (2004). Cosa Nostra. A history of the Sicilian Mafia, London: Coronet ISBN 0-340-82435-2

- Macmillan, Margaret (2002). Paris 1919: Six Months That Changed the World, New York: Random House, ISBN 0-375-76052-0

- Morley Sachar, Howard (2006). A History of the Jews in the Modern World, Vintage Books, ISBN 9781400030972

- Rossini, Daniela (2008). Woodrow Wilson and the American Myth in Italy: Culture, Diplomacy, and War Propaganda, Cambridge (MA)/London: Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-02824-1

- Sarti, Roland (2004). Italy: a reference guide from the Renaissance to the present, New York: Facts on File Inc., ISBN 0-81607-474-7

- Seton-Watson, Christopher (1967). Italy from liberalism to fascism, 1870–1925, New York: Taylor & Francis, 1967 ISBN 0-416-18940-7

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sidney Sonnino. |

- (in Italian) Centro Studi Sidney Sonnino

- Newspaper clippings about Sidney Sonnino in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Alessandro Fortis |

Prime Minister of Italy 1906 |

Succeeded by Giovanni Giolitti |

| Preceded by Alessandro Fortis |

Italian Minister of the Interior 1906 |

Succeeded by Giovanni Giolitti |

| Preceded by Giovanni Giolitti |

Prime Minister of Italy 1909–1910 |

Succeeded by Luigi Luzzatti |

| Preceded by Giovanni Giolitti |

Italian Minister of the Interior 1909–1910 |

Succeeded by Luigi Luzzatti |

| Preceded by Antonino Paternò Castello |

Foreign Minister of Italy 1914–1919 |

Succeeded by Tommaso Tittoni |

.svg.png)