Shrew

Shrews (family Soricidae) are small mole-like mammals classified in the order Eulipotyphla. True shrews are not to be confused with treeshrews, otter shrews, elephant shrews, or the West Indies shrews, which belong to different families or orders.

| Shrews[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Eulipotyphla |

| Family: | Soricidae G. Fischer, 1814 |

| Subfamilies | |

| |

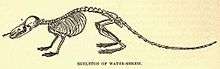

Although its external appearance is generally that of a long-nosed mouse, a shrew is not a rodent, as mice are. It is, in fact, a much closer relative of hedgehogs and moles, and shrews are related to rodents only to the extent that both belong to the Boreoeutheria magnorder – together with humans, monkeys, cats, dogs, horses, rhinos, cattle, pigs, whales, bats, and others. Shrews have sharp, spike-like teeth, not the familiar gnawing front incisor teeth of rodents.

Shrews are distributed almost worldwide; of the major tropical and temperate land masses, only New Guinea, Australia, and New Zealand have no native shrews; in South America shrews appeared only relatively recently, as a result of the Great American Interchange, and are present only in the northern Andes. In terms of species diversity, the shrew family is the fourth-most successful mammal family, being exceeded only by the muroid rodent families Muridae and Cricetidae and the bat family Vespertilionidae.

Characteristics

All shrews are tiny, most no larger than a mouse. The largest species is the Asian house shrew (Suncus murinus) of tropical Asia, which is about 15 cm (6 in) long and weighs around 100 g (4 oz)[2] several are very small, notably the Etruscan shrew (Suncus etruscus), which at about 3.5 cm (1.4 in) and 1.8 g (0.063 oz) is the smallest known living terrestrial mammal.

In general, shrews are terrestrial creatures that forage for seeds, insects, nuts, worms, and a variety of other foods in leaf litter and dense vegetation, but some specialise in climbing trees, living underground, living under snow, or even hunting in water. They have small eyes and generally poor vision, but have excellent senses of hearing and smell.[3] They are very active animals, with voracious appetites. Shrews have unusually high metabolic rates, above that expected in comparable small mammals.[4] Shrews in captivity can eat 1/2 to 2 times their own body weight in food daily.[5]

They do not hibernate, but are capable of entering torpor. In winter, many species undergo morphological changes that drastically reduce their body weight. Shrews can lose between 30% and 50% of their body weight, shrinking the size of bones, skull, and internal organs.[6]

Whereas rodents have gnawing incisors that grow throughout life, the teeth of shrews wear down throughout life, a problem made more extreme because they lose their milk teeth before birth, so have only one set of teeth throughout their lifetimes. In some species, exposed areas of the teeth are dark red due to the presence of iron in the tooth enamel. The iron reinforces the surfaces that are exposed to the most stress, which helps prolong the life of the teeth. This adaptation is not found in species with lower metabolism, which don't have to eat as much and therefore don't wear down the enamel to the same degree. The only other mammals with pigmented enamel are the incisors of rodents.[7] Apart from the first pair of incisors, which are long and sharp, and the chewing molars at the back of the mouth, the teeth of shrews are small and peg-like, and may be reduced in number. The dental formula of shrews is:3.1.1-3.31-2.0-1.1.3

Shrews are fiercely territorial, driving off rivals, and coming together only to mate. Many species dig burrows for catching food and hiding from predators, although this is not universal.[3]

Female shrews can have up to 10 litters a year; in the tropics, they breed all year round; in temperate zones, they cease breeding only in the winter. Shrews have gestation periods of 17–32 days. The female often becomes pregnant within a day or so of giving birth, and lactates during her pregnancy, weaning one litter as the next is born.[3] Shrews live 12 to 30 months.[8]

Shrews are unusual among mammals in a number of respects. Unlike most mammals, some species of shrews are venomous. Shrew venom is not conducted into the wound by fangs, but by grooves in the teeth. The venom contains various compounds, and the contents of the venom glands of the American short-tailed shrew are sufficient to kill 200 mice by intravenous injection. One chemical extracted from shrew venom may be potentially useful in the treatment of high blood pressure, while another compound may be useful in the treatment of some neuromuscular diseases and migraines.[9] The saliva of the northern short-tailed shrew (Blarina brevicauda) contains soricidin, a peptide which has been studied for use in treating ovarian cancer.[10] Also, along with the bats and toothed whales, some species of shrews use echolocation. Unlike most other mammals, shrews lack zygomatic bones (also called the jugals), so have incomplete zygomatic arches.

Echolocation

The only terrestrial mammals known to echolocate are two genera (Sorex and Blarina) of shrews, the tenrecs of Madagascar, bats, and the solenodons. These include the Eurasian or common shrew (Sorex araneus) and the American vagrant shrew (Sorex vagrans) and northern short-tailed shrew (Blarina brevicauda). These shrews emit series of ultrasonic squeaks.[11][12] By nature the shrew sounds, unlike those of bats, are low-amplitude, broadband, multiharmonic, and frequency modulated.[12] They contain no "echolocation clicks" with reverberations and would seem to be used for simple, close-range spatial orientation. In contrast to bats, shrews use echolocation only to investigate their habitats rather than additionally to pinpoint food.[12]

Except for large and thus strongly reflecting objects, such as a big stone or tree trunk, they probably are not able to disentangle echo scenes, but rather derive information on habitat type from the overall call reverberations. This might be comparable to human hearing whether one calls into a beech forest or into a reverberant wine cellar.[12]

Classification

The 385 shrew species are placed in 26 genera,[13] which are grouped into three living subfamilies: Crocidurinae (white-toothed shrews), Myosoricinae (African shrews), and Soricinae (red-toothed shrews). In addition, the family contains the extinct subfamilies Limnoecinae, Crocidosoricinae, Allosoricinae, and Heterosoricinae (although Heterosoricinae is also commonly considered a separate family).

- Family Soricidae

- Subfamily Crocidurinae

- Subfamily Myosoricinae

- Subfamily Soricinae

- Tribe Anourosoricini

- Tribe Blarinellini

- Tribe Blarinini

- Tribe Nectogalini

- Tribe Notiosoricini

- Tribe Soricini

References

- Hutterer R (2005). Wilson D, Reeder D (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 223–300. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- Louch CD, Ghosh AK, Pal BC (1966). "Seasonal Changes in Weight and Reproductive Activity of Suncus murinus in West Bengal, India". Journal of Mammalogy. 47 (1): 73–78. JSTOR 1378070.

- Barnard CJ (1984). Macdonald DW (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Mammals. New York: Facts on File. pp. 758–763. ISBN 0-87196-871-1.

- William J, Platt WJ (1974). "Metabolic Rates of Short-Tailed Shrews". Physiological Zoology. 47 (2): 75–90. JSTOR 30155625.

- Reid F (2009). A Field Guide to the Mammals of Central America and Southeast Mexico. pp. 63–64.

- Churchfield S (January 1990). The natural history of shrews. ISBN 978-0-8014-2595-0.

- Wible J. "Why Do Some Shrews Have Dark Red Teeth?". Carnegie Museum.

- Macdonald DW, ed. (2006). The Encyclopedia of Mammals. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-920608-2.

- Piper R (2007). Extraordinary Animals: An Encyclopedia of Curious and Unusual Animals. Greenwood Press.

- "BioProspecting NB, Inc's novel ovarian cancer treatment found effective in animal cancer model". 8 Apr 2009. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- Tomasi TE (1979). "Echolocation by the Short-Tailed Shrew Blarina brevicauda". Journal of Mammalogy. 60 (4): 751–9. doi:10.2307/1380190. JSTOR 1380190.

- Siemers BM, Schauermann G, Turni H, von Merten S (October 2009). "Why do shrews twitter? Communication or simple echo-based orientation". Biology Letters. 5 (5): 593–6. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2009.0378. PMC 2781971. PMID 19535367.

- Wilson DE, Reeder DM (2011). "Class Mammalia Linnaeus, 1758. In: Zhang, Z.-Q. (ed.) Animal biodiversity: An outline of higher-level classification and survey of taxonomic richness" (PDF). Zootaxa. 3148: 56–60. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.3148.1.9.

Further reading

- Buchler ER (November 1976). "The use of echolocation by the wandering shrew (Sorex vagrans)". Animal Behaviour. 24 (4): 858–73. doi:10.1016/S0003-3472(76)80016-4.

- Busnel RG, ed. (1963). Acoustic Behaviour of Animals. Amsterdam: Elsevier Publishing Company.

- Forsman KA, Malmquist MG (1988). "Evidence for echolocation in the common shrew, Sorex araneus". Journal of Zoology. 216 (4): 655. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1988.tb02463.x.

- Gould E (1962). Evidence for echolocation in shrews (Ph.D. thesis). Tulane University.

- Gould E, Negus NC, Novick A (June 1964). "Evidence for echolocation in shrews". The Journal of Experimental Zoology. 156: 19–37. doi:10.1002/jez.1401560103. PMID 14189919.

- Hutterer R (1976). Deskriptive und vergleichende Verhaltensstudien an der Zwergspitzmaus, Sorex minutus L., und der Waldspitzmaus, Sorex araneus L. (Soricidae - Insectivora - Mammalia) (Ph.D. Thesis) (in German). Univ. Wien. OCLC 716064334.

- Hutterer R, Vogel P (1977). "Abwehrlaute afrikanischer Spitzmäuse der Gattung Crocidura Wagler, 1832 und ihre systematische Bedeutung" (PDF). Bonner zoologische Beiträge (in German). 28 (3/4): 218–27.

- Hutterer R, Vogel P, Frey H, Genoud M (1979). "Vocalization of the shrews Suncus etruscus and Crocidura russula during normothermia and torpor". Acta Theriologica. 24 (21): 267–71. doi:10.4098/AT.arch.79-28.

- Irwin DV, Baxter RM (1980). "Evidence against the use of echolocation by Crocidura f. flavescens (Soricidae)". Säugetierkundliche Mitteilungen. 28 (4): 323.

- Kahmann H, Ostermann K (July 1951). "[Perception of production of high tones by small mammals]" [Perception of production of high tones by small mammals]. Experientia (in German). 7 (7): 268–9. doi:10.1007/BF02154548. PMID 14860152.

- Köhler D, Wallschläger D (1987). "Über die Lautäußerungen der Wasserspitzmaus, Neomys fodiens (Insectivora: Soricidae)" [On vocalization of the european water shrew Neomys fodiens (Insectivora: Soricidae)]. Zoologische Jahrbücher (in German). 91 (1): 89–99.

- Sales G, Pye D (1974). Ultrasonic communication by animals. London.